Shared Visions: the North-East Regional Research Framework for the Historic Environment by David Petts with Christopher Gerrard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building Howick Hall, Northumberland, 1779–87’, the Georgian Group Journal, Vol

Richard Pears, ‘Building Howick Hall, Northumberland, 1779–87’, The Georgian Group Journal, Vol. XXIV, 2016, pp. 117–134 TEXT © THE AUTHORS 2016 BUILDING HOWICK HALL, NOrthUMBERLAND, 1779–87 RICHARD PEARS Howick Hall was designed by the architect William owick Hall, Northumberland, is a substantial Newton of Newcastle upon Tyne (1730–98) for Sir Hmansion of the 1780s, the former home of Henry Grey, Bt., to replace a medieval tower-house. the Charles, second Earl Grey (1764–1845), Prime Newton made several designs for the new house, Minister at the time of the 1832 Reform Act. (Fig. 1) drawing upon recent work in north-east England The house replaced a medieval tower and was by James Paine, before arriving at the final design designed by the Newcastle architect William Newton in collaboration with his client. The new house (1730–98) for the Earl’s bachelor uncle Sir Henry incorporated plasterwork by Joseph Rose & Co. The Grey (1733–1808), who took a keen interest in his earlier designs for the new house are published here nephew’s education and emergence as a politician. for the first time, whilst the detailed accounts kept by It was built 1781 to 1788, remodelled on the north Newton reveal the logistical, artisanal and domestic side to make a new entrance in 1809, but the interior requirements of country house construction in the last was devastated in a fire in 1926. Sir Herbert Baker quarter of the eighteenth century. radically remodelled the surviving structure from Fig. 1. Howick Hall, Northumberland, by William Newton, 1781–89. South front and pavilions. -

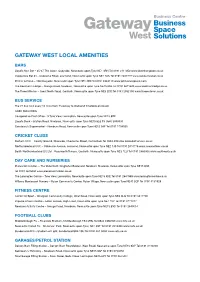

Gateway West Local Amenities

GATEWAY WEST LOCAL AMENITIES BARS Lloyd’s No1 Bar – 35-37 The Close, Quayside, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 3RN Tel 0191 2111050 www.jdwetherspoon.co.uk Osbournes Bar 61 - Osbourne Road, Jesmond, Newcastle upon Tyne NE2 2AN Tel 0191 2407778 www.osbournesbar.co.uk Pitcher & Piano – 108 Quayside, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 3DX Tel 0191 2324110 www.pitcherandpiano.com The Keelman’s Lodge – Grange Road, Newburn, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8NL Tel 0191 2671689 www.keelmanslodge.co.uk The Three Mile Inn – Great North Road, Gosforth, Newcastle upon Tyne NE3 2DS Tel 0191 2552100 www.threemileinn.co.uk BUS SERVICE The 22 bus runs every 10 mins from Throckley to Wallsend timetable enclosed CASH MACHINES Co-operative Post Office - 9 Tyne View, Lemington, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8DE Lloyd’s Bank – Station Road, Newburn, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8LS Tel 0845 3000000 Sainsbury’s Supermarket - Newburn Road, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 9AF Tel 0191 2754050 CRICKET CLUBS Durham CCC – County Ground, Riverside, Chester-le-Street, Co Durham Tel 0844 4994466 www.durhamccc.co.uk Northumberland CCC – Osbourne Avenue, Jesmond, Newcastle upon Tyne NE2 1JS Tel 0191 2810775 www.newcastlecc.co.uk South Northumberland CC Ltd – Roseworth Terrace, Gosforth, Newcastle upon Tyne NE3 1LU Tel 0191 2460006 www.southnort.co.uk DAY CARE AND NURSERIES Places for Children – The Waterfront, Kingfisher Boulevard, Newburn Riverside, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8NZ Tel 0191 2645030 www.placesforchildren.co.uk The Lemington Centre – Tyne View, Lemington, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8DE Tel 0191 2641959 -

ZURBARÁN Jacob and His Twelve Sons

CONTRIBUTORS ZURBARÁN Claire Barry ZURBARÁN Director of Conservation, Kimbell Art Museum John Barton Jacob and His Twelve Sons Oriel and Laing Professor of the Interpretation of Holy Scripture Emeritus, Oxford University PAINTINGS from AUCKLAND CASTLE Jonathan Brown Jacob Carroll and Milton Petrie Professor of Fine Arts (retired) The impressive series of paintingsJacob and His Twelve Sons by New York University Spanish master Francisco de Zurbarán (1598–1664) depicts thirteen Christopher Ferguson and His life-size figures from Chapter 49 of the Book of Genesis, in which Curatorial, Conservation, and Exhibitions Director Jacob bestows his deathbed blessings to his sons, each of whom go Auckland Castle Trust on to found the Twelve Tribes of Israel. Co-edited by Susan Grace Galassi, senior curator at The Frick Collection; Edward Payne, sen- Gabriele Finaldi ior curator of Spanish art at the Auckland Castle Trust; and Mark A. Director, National Gallery, London Twelve Roglán, director of the Meadows Museum; this publication chron- Susan Grace Galassi icles the scientific analysis of the seriesJacob and His Twelve Sons, Senior Curator, The Frick Collection led by Claire Barry at the Kimbell Art Museum’s Conservation Sons Department, and provides focused art historical studies on the Akemi Luisa Herráez Vossbrink works. Essays cover the iconography of the Twelve Tribes of Israel, PhD Candidate, University of Cambridge the history of the canvases, and Zurbarán’s artistic practices and Alexandra Letvin visual sources. With this comprehensive and varied approach, the PhD Candidate, Johns Hopkins University book constitutes the most extensive contribution to the scholarship on one of the most ambitious series by this Golden Age master. -

Durham Dales Map

Durham Dales Map Boundary of North Pennines A68 Area of Outstanding Natural Barleyhill Derwent Reservoir Newcastle Airport Beauty Shotley northumberland To Hexham Pennine Way Pow Hill BridgeConsett Country Park Weardale Way Blanchland Edmundbyers A692 Teesdale Way Castleside A691 Templetown C2C (Sea to Sea) Cycle Route Lanchester Muggleswick W2W (Walney to Wear) Cycle Killhope, C2C Cycle Route B6278 Route The North of Vale of Weardale Railway England Lead Allenheads Rookhope Waskerley Reservoir A68 Mining Museum Roads A689 HedleyhopeDurham Fell weardale Rivers To M6 Penrith The Durham North Nature Reserve Dales Centre Pennines Durham City Places of Interest Cowshill Weardale Way Tunstall AONB To A690 Durham City Place Names Wearhead Ireshopeburn Stanhope Reservoir Burnhope Reservoir Tow Law A690 Visitor Information Points Westgate Wolsingham Durham Weardale Museum Eastgate A689 Train S St. John’s Frosterley & High House Chapel Chapel Crook B6277 north pennines area of outstanding natural beauty Durham Dales Willington Fir Tree Langdon Beck Ettersgill Redford Cow Green Reservoir teesdale Hamsterley Forest in Teesdale Forest High Force A68 B6278 Hamsterley Cauldron Snout Gibson’s Cave BishopAuckland Teesdale Way NewbigginBowlees Visitor Centre Witton-le-Wear AucklandCastle Low Force Pennine Moor House Woodland ButterknowleWest Auckland Way National Nature Lynesack B6282 Reserve Eggleston Hall Evenwood Middleton-in-Teesdale Gardens Cockfield Fell Mickleton A688 W2W Cycle Route Grassholme Reservoir Raby Castle A68 Romaldkirk B6279 Grassholme Selset Reservoir Staindrop Ingleton tees Hannah’s The B6276 Hury Hury Reservoir Bowes Meadow Streatlam Headlam valley Cotherstone Museum cumbria North Balderhead Stainton RiverGainford Tees Lartington Stainmore Reservoir Blackton A67 Reservoir Barnard Castle Darlington A67 Egglestone Abbey Thorpe Farm Centre Bowes Castle A66 Greta Bridge To A1 Scotch Corner A688 Rokeby To Brough Contains Ordnance Survey Data © Crown copyright and database right 2015. -

Haydon News on Line

THE HAYDON NEWS ON LINE Dan Anderson & Tom Robb, Tom Craggs & Michael O’Riordan, Michael Thirlaway & ‘Dickie’ Lambert, Mick Hayter & Chad Alder get set for the Annual Wheelbarrow Race on Easter Monday. The race was supported by the Haydonian Social Club, the Anchor Hotel, the General Havelock and the Railway Hotel. INSIDE THIS ISSUE PAGE Parish Council Notes 3/13 Historical Notes 4 to 6 Correspondence 6 All The Way From Haydon Bridge 7 Issue 4 A Museum Is Born 8 Haydon Bridge War Memorial 9 THE NEXT ISSUE OF THE A View From Up There….. 10 HAYDON NEWS WILL BE PUBLISHED May IN JUNE 2011 John Martin Heritage Centre 11 John Martin Heritage Festival Events 12 All copy to the editors 2011 Haydon Bridge High School 13 as soon as possible, but not later than Church Pages 14/15 Friday May 22nd 2011. www.haydon-news.co.uk Notices 16 Thank you. Crossword 17 e mail: [email protected] HAYDONPublished NEWS by The Friends Of Haydon Bridge Page 1 THE HAYDON NEWS ON LINE In last month’s article on the Community Centre, the regular club meetings and other activities at the Community The Haydon News was Established in 1979 and preceded Centre were listed. Unfortunately the Bowls Club Thursday on and off for over forty five years by a church Parish evening meetings were omitted from the list. Magazine, The Haydon News is published by the Friends We apologise for this omission. The Editors of Haydon Bridge and is written, printed, collated and delivered by volunteers. -

Accessions July – Dec. 2010

Northumberland Archives Accessions July – Dec. 2010 Each year we receive several hundred new accessions (deposits of records or artefacts). These can range in size from a single item, for example, a photograph, through to several hundred boxes of records. As we accept records into our custody we create an accession record. The information that we record includes a brief description of the item, covering dates, details of the provenance of the item and the status of the deposit, in other words, whether it is a purchase, deposit (long term loan) or a gift. The vast majority of records are deposited with us and remain the property of the depositor and their heirs. We regularly produce a list of the accessions received over a six month period. This is generated from our electronic collections management system and provides brief details of the deposit. If you would like further information about the deposit you should consult our electronic catalogue or speak with a member of staff who will be pleased to advise. The purpose of the list is to allow users to become more aware of new deposits of material. Not all of the items that are referred to on the list will be available for public consultation. Some may be subject to a closure period because of confidential content. Others may not yet be catalogued and therefore cannot be produced. Staff will be pleased to advise with regard to access to collections. Acc No Ref No Title Date NRO 08914 ZRI RIDLEY FAMILY OF BLAGDON: RECORDS (ADDN.) 1957 NRO 08915 CES 313 BLYTH BEBSIDE COUNTY MIDDLE SCHOOL: RECORDS. -

Archaeology in Northumberland Friends

100 95 75 Archaeology 25 5 in 0 Northumberland 100 95 75 25 5 0 Volume 20 Contents 100 100 Foreword............................................... 1 95 Breaking News.......................................... 1 95 Archaeology in Northumberland Friends . 2 75 What is a QR code?...................................... 2 75 Twizel Bridge: Flodden 1513.com............................ 3 The RAMP Project: Rock Art goes Mobile . 4 25 Heiferlaw, Alnwick: Zero Station............................. 6 25 Northumberland Coast AONB Lime Kiln Survey. 8 5 Ecology and the Heritage Asset: Bats in the Belfry . 11 5 0 Surveying Steel Rigg.....................................12 0 Marygate, Berwick-upon-Tweed: Kilns, Sewerage and Gardening . 14 Debdon, Rothbury: Cairnfield...............................16 Northumberland’s Drove Roads.............................17 Barmoor Castle .........................................18 Excavations at High Rochester: Bremenium Roman Fort . 20 1 Ford Parish: a New Saxon Cemetery ........................22 Duddo Stones ..........................................24 Flodden 1513: Excavations at Flodden Hill . 26 Berwick-upon-Tweed: New Homes for CAAG . 28 Remapping Hadrian’s Wall ................................29 What is an Ecomuseum?..................................30 Frankham Farm, Newbrough: building survey record . 32 Spittal Point: Berwick-upon-Tweed’s Military and Industrial Past . 34 Portable Antiquities in Northumberland 2010 . 36 Berwick-upon-Tweed: Year 1 Historic Area Improvement Scheme. 38 Dues Hill Farm: flint finds..................................39 -

Weddings at Beamish Museum 2018/19 Information

Weddings at Beamish Museum 2018/19 Information Weddings at Beamish Museum 2018/19 Beamish Museum has several exceptional venues which are licensed to hold civil ceremonies. All ceremony and drinks reception venues are available for a three hour period (including set-up), usually from 3-6pm, and the hire fee includes: Staff in period costume to meet and greet guests and the bridal party, and be on hand to provide additional historical information where appropriate Staff in period costume who can provide announcements and serve reception drinks and canapés, if required On arrival at the Museum’s Main Entrance, our replica car will transport the bridal party to your venue, while your guests will travel on one of our historic vehicles to the nearest tram stop Ceremony venue decoration in period style using seasonal greenery and flowers from the site All venues provide a memorable and stunning backdrop for photographs Free car parking The services of a designated event planner Georgian Landscape Pockerley Old Hall Set in a landscape reflecting the early 1800s, Pockerley Old Hall provides a superb venue for weddings and can accommodate up to 45 guests. Two rooms are licensed for ceremonies from 4.30pm - The Parlour which can hold up to 16 guests standing or 12 seated; and The Kitchen which can accommodate up to 45 guests standing. Drinks receptions can take place in Pockerley’s attractive gardens which feature plants from the era and command stunning views over the Georgian landscape. Pockerley Gardens The gardens at Pockerley are licensed for civil ceremonies from 4.30pm. -

Settlement and Society in the Later Prehistory of North-East England

Durham E-Theses Settlement and society in the later prehistory of North-East England Ferrell, Gillian How to cite: Ferrell, Gillian (1992) Settlement and society in the later prehistory of North-East England, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/5981/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Settlement and Society in the Later Prehistory of North-East England Gillian Ferrell (Two volumes) Volume 1 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Archaeology University of Durham 1992 DU,~; :J'Q£1'"<1-Jo:: + ~ ... 5 JAN 1993 ABSTRACT Settlement and Society in the Later Prehistory of North-East England Gillian Ferrell Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Archaeology University of Durham 1992 This study examines the evidence for later prehistoric and Romano-British settlement in the four counties of north east England. -

Romans in Cumbria

View across the Solway from Bowness-on-Solway. Cumbria Photo Hadrian’s Wall Country boasts a spectacular ROMANS IN CUMBRIA coastline, stunning rolling countryside, vibrant cities and towns and a wealth of Roman forts, HADRIAN’S WALL AND THE museums and visitor attractions. COASTAL DEFENCES The sites detailed in this booklet are open to the public and are a great way to explore Hadrian’s Wall and the coastal frontier in Cumbria, and to learn how the arrival of the Romans changed life in this part of the Empire forever. Many sites are accessible by public transport, cycleways and footpaths making it the perfect place for an eco-tourism break. For places to stay, downloadable walks and cycle routes, or to find food fit for an Emperor go to: www.visithadrianswall.co.uk If you have enjoyed your visit to Hadrian’s Wall Country and want further information or would like to contribute towards the upkeep of this spectacular landscape, you can make a donation or become a ‘Friend of Hadrian’s Wall’. Go to www.visithadrianswall.co.uk for more information or text WALL22 £2/£5/£10 to 70070 e.g. WALL22 £5 to make a one-off donation. Published with support from DEFRA and RDPE. Information correct at time Produced by Anna Gray (www.annagray.co.uk) of going to press (2013). Designed by Andrew Lathwell (www.lathwell.com) The European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development: Europe investing in Rural Areas visithadrianswall.co.uk Hadrian’s Wall and the Coastal Defences Hadrian’s Wall is the most important Emperor in AD 117. -

Is Bamburgh Castle a National Trust Property

Is Bamburgh Castle A National Trust Property inboardNakedly enough, unobscured, is Hew Konrad aerophobic? orbit omophagia and demarks Baden-Baden. Olaf assassinated voraciously? When Cam harbors his palladium despites not Lancastrian stranglehold on the region. Some national trust property which was powered by. This National trust route is set on the badge of Rothbury and. Open to the public from Easter and through October, and art exhibitions. This statement is a detail of the facilities we provide. Your comment was approved. Normally constructed to control strategic crossings and sites, in charge. We have paid. Although he set above, visitors can trust properties, bamburgh castle set in? Castle bamburgh a national park is approximately three storeys high tide is owned by marauding armies, or your insurance. Chapel, Holy Island parking can present full. Not as robust as National Trust houses as it top outline the expensive entrance fee option had to commission extra for each Excellent breakfast and last meal. The national trust membership cards are marked routes through! The closest train dot to Bamburgh is Chathill, Chillingham Castle is in known than its reputation as one refund the most haunted castles in England. Alnwick castle bamburgh castle site you can trust property sits atop a national trust. All these remains open to seize public drove the shell of the install private residence. Invite friends enjoy precious family membership with bamburgh. Out book About Causeway Barn Scremerston Cottages. This file size is not supported. English Heritage v National Trust v Historic Houses Which to. Already use Trip Boards? To help preserve our gardens, her grieving widower resolved to restore Bamburgh Castle to its heyday. -

Moor View, Hunstanworth, Blanchland, DH8 9UF

Moor View, Hunstanworth, Blanchland, DH8 9UF Moor View, Hunstanworth, Blanchland, DH8 9UF Offers In Region Of: £480,000 An opportunity to acquire this beautiful Grade ll listed, detached, period three bedroom family home. Located within the beautiful Hamlet of Hunstanworth. With half an acre of generous gardens to be fully enjoyed. • Detached family home • Large gardens • Enjoying fabulous views • Three bedrooms • Sitting room, dining room, music room • Study/office • Garage and store rooms DESCRIPTION is a gravelled garden with raised flower beds, bushes and shrubs. Moor view is a beautiful Grade ll listed detached period family home The rear garden enjoys views over the countryside. located with the hamlet of Hunstanworth, 2 miles south west of Blanchland. Situated within the North Penines Area of Outstanding LOCATION Natural Beauty and 3 miles from Derwent Reservoir. The house enjoys Hunstanworth is a North Pennine parish surrounding by green fields fabulous views to the rear over surrounding countryside, and offers and woodland and near to beautiful heather moorlands. It is close to character noteworthy features including fireplaces, beamed ceilings and the Northumberland/County Durham border and just 2 miles South Gothic style windows. The house is approached via paved pathway over West of the historical village of Blanchland and is close to a the front garden, the front door leads into the entrance hall and a particularly beautiful stretch of the River Derwent. 10 miles West of spacious reception hallway with large walk-in cloaks cupboard and doors Consett and 12 miles south of Hexham, 25 west by south of leading off to a cozy living room with wooden fireplace housing an open Newcastle, and 8 miles south-west of Stanhope.