Home: a Tale of Few Cities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Holiday Events Begin Thanksgiving Weekend in Downtown Westfield

The Latest from Downtown Westfield NJ, a Classic Town for Modern Families November 2017 IN THIS ISSUE: Holiday Events begin Thanksgiving in Westfield, Grand Openings, Facade Renovations, Food & Wine Seasonal & Savory, Seasonal Sweets, Spotlight On: Brummer's Chocolates, Upcoming Events, Best of NJ 2017, Retail Buzz: The French Martini, Fitness Corner, Best Bets, Gift Coins, Historical Walk Holiday Events Begin Thanksgiving Weekend in Downtown Westfield The holiday season is the perfect time to enjoy shopping, dining and celebrating in our classic town for modern families! Since there's no place like home, Westfield is the place where families and friends share good food, exchange gifts and create awesome memories. The Downtown Westfield Corporation (DWC) is proud to sponsor the following annual holiday events beginning Thanksgiving weekend: Photos with Santa & Mrs. Claus (Co-Sponsored by Lord & Taylor) November 24- 26 at Lord & Taylor, Westfield 609 North Ave. W., Westfield, NJ Friday & Saturday 1-7pm, Sunday 1-4pm Free 5" x 7" Photo with donation of 2 cans of non -perishable food for the Holy Trinity Westfield Food Pantry. Nominal shipping fee will apply. Additional online photo packages may be purchased from Paul Mecca of Westfield Neighbors Magazine, www.Meccography.com Black Friday Shopping Friday, November 24 Most downtown stores will be open with exciting promotions. Skip Route 22 and the malls and shop locally instead! Small Business Saturday Saturday, November 25 Shop Small, Dine Small, Shop Westfield! Enjoy FREE PARKING ALL DAY courtesy of The Town of Westfield! Small Business Saturday Roaming Entertainment Saturday, November 25 Santa & Mrs. Claus 10am-noon Yuletide Carolers 1-2pm NJ Workshop for the Arts Brass Quintet 2:30-4pm The Harmonics 3-5pm Annual Tree Lighting with Santa & Mrs. -

Potato - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Potato - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Log in / create account Article Talk Read View source View history Our updated Terms of Use will become effective on May 25, 2012. Find out more. Main page Potato Contents From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Featured content Current events "Irish potato" redirects here. For the confectionery, see Irish potato candy. Random article For other uses, see Potato (disambiguation). Donate to Wikipedia The potato is a starchy, tuberous crop from the perennial Solanum tuberosum Interaction of the Solanaceae family (also known as the nightshades). The word potato may Potato Help refer to the plant itself as well as the edible tuber. In the region of the Andes, About Wikipedia there are some other closely related cultivated potato species. Potatoes were Community portal first introduced outside the Andes region four centuries ago, and have become Recent changes an integral part of much of the world's cuisine. It is the world's fourth-largest Contact Wikipedia food crop, following rice, wheat and maize.[1] Long-term storage of potatoes Toolbox requires specialised care in cold warehouses.[2] Print/export Wild potato species occur throughout the Americas, from the United States to [3] Uruguay. The potato was originally believed to have been domesticated Potato cultivars appear in a huge variety of [4] Languages independently in multiple locations, but later genetic testing of the wide variety colors, shapes, and sizes Afrikaans of cultivars and wild species proved a single origin for potatoes in the area -

Type of Ritual Food in Odisha: a Case Study of Eastern Odisha

TYPE OF RITUAL FOOD IN ODISHA: A CASE STUDY OF EASTERN ODISHA Dr. Sikhasree Ray Post Doctorate Scholar Post Graduate & Research Institute Deccan College Pune-411006, India Abstract: This paper attempts to understand the importance, situations and context in food consumption focusing on the rituals and traditions. Odisha, a state in the eastern part of India, being famous for fair and festivals shows a variety of food items that are associated to various rituals either religious or secular. The ritual foods are mainly made from the ingredients that are locally available or most popular in Odisha. Deep understanding of the ritual foods of Odisha can show its continuity with the past and reflect cultural ideas about eating for good health, nutrition and many more. This traditional food items and its making procedures are vanishing or modernizing due to introduction of new food items, ingredients and Western food. Hence the present study has tried to document and describe various type of ritual food in Eastern Odisha, the ingredients used and the way of preparation. Keywords: Ritual, Mahaprasad, Food I. INTRODUCTION: Rituals of various kinds are a feature of almost all known human societies, past or present. As societies and social behaviors became complex, there emerged beliefs and faiths which governed them. One of the creations out of this was ritual. The rituals got associated to different aspects of society and are performed in different points of the year by different communities or classes of people. It is performed mainly for their symbolic value, prescribed by a religion or by the traditions of a community. -

17.03.2015 by an Order Passed by the Hon'ble Supreme Court in Civil

17.03.2015 SUPPLEMENTARY LIST SUPPLEMENTARY LIST FOR TODAY IN CONTINUATION OF THE ADVANCE LIST ALREADY CIRCULATED. THE WEBSITE OF DELHI HIGH COURT IS www.delhihighcourt.nic.in INDEX PRONOUNCEMENT OF JUDGMENTS ------------> J- 1 TO 03 REGULAR MATTERS -----------------------> R- 1 TO 63 FINAL MATTERS (ORIGINAL SIDE) ---------> F- 1 TO 11 ADVANCE LIST --------------------------> 1 TO 84 APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST)----> 85 TO 106 (FIRST PART) APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST)----> 107 TO 116 (SECOND PART) COMPANY -------------------------------> 117 TO 119 ORIGINAL SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY I)--------> 120 TO 130 SECOND SUPPLEMENTARY ------------------> 131 TO NOTES 1. Urgent mentioning may be made before Hon'ble DB-II at 10.30 A.M. By an order passed by the Hon'ble Supreme Court in Civil Appeal No. 7400/2014, it has been held that against an order passed by the Armed Forces Tribunal, a Writ Petition under Article 226 of the Constitution of India cannot be entertained by the High Court and that the remedy for the aggrieved person is in terms of Section 30 and 31 of the Armed Forces Tribunal Act, 2007. Accordingly, the Writ Petitions pending in this High Court against the orders passed by the Armed Forces Tribunal will be listed for directions before Hon'ble DB-III on 20.03.2015. DELETIONS 1. W.P.(C) 628/2015 listed before Hon'ble DB-IV at item No.17 is deleted as the same is fixed for 07.04.2015. 2. W.P.(C) 5883/2012 listed before Hon'ble Mr. Justice Valmiki J. Mehta at item No.6 is deleted as the same is listed before Hon'ble Mr. -

View in 1986: "The Saccharine Sweet, Icky Drink? Yes, Well

Yashwantrao Chavan Maharashtra Open University V101:B. Sc. (Hospitality and Tourism Studies) V102: B.Sc. (Hospitality Studies & Catering Ser- vices) HTS 202: Food and Beverage Service Foundation - II YASHWANTRAO CHAVAN MAHARASHTRA OPEN UNIVERSITY (43 &Øا "••≤°• 3•≤©£• & §°© )) V101: B. Sc. Hospitality and Tourism Studies (2016 Pattern) V102: B. Sc. Hospitality Studies and Catering Services (2016 Pattern) Developed by Dr Rajendra Vadnere, Director, School of Continuing Education, YCMOU UNIT 1 Non Alcoholic Beverages & Mocktails…………...9 UNIT 2 Coffee Shop & Breakfast Service ………………69 UNIT 3 Food and Beverage Services in Restaurants…..140 UNIT 4 Room Service/ In Room Dinning........................210 HTS202: Food & Beverage Service Foundation -II (Theory: 4 Credits; Total Hours =60, Practical: 2 Credits, Total Hours =60) Unit – 1 Non Alcoholic Beverages & Mocktails: Introduction, Types (Tea, Coffee, Juices, Aerated Beverages, Shakes) Descriptions with detailed inputs, their origin, varieties, popular brands, presentation and service tools and techniques. Mocktails – Introduction, Types, Brief Descriptions, Preparation and Service Techniques Unit – 2 Coffee Shop & Breakfast Service: Introduction, Coffee Shop, Layout, Structure, Breakfast: Concept, Types & classification, Breakfast services in Hotels, Preparation for Breakfast Services, Mise- en-place and Mise-en-scene, arrangement and setting up of tables/ trays, Functions performed while on Breakfast service, Method and procedure of taking a guest order, emerging trends in Breakfast -

Tania Gets Lost

Tania Gets Lost Copyright © 2019 by Kanika G All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher, except for the use of brief quotations in a book review. First Edition, 2019. Website https://kanikag.com/ 2 An Interesting Discovery "Tania, don't you want to take a nap?" Mama called out. "No Mama. I'm not sleepy. You know, I don't usually sleep in the afternoon." Tania replied. "Yes, but I thought this morning's trek would have worn you out. See, Sonia is fast asleep." Mama said pointing to baby Sonia on her bed. "Tanisha and I are not at all sleepy Mama. This place is so exciting. We want to do some exploring. Can we do that now, Mama?" "I have no idea how you have so much energy, but if you feel up to it, I don't see why not. Have fun. Papa and I are off to bed. I'm sure Tanisha's parents will want some rest too." Mama yawned and headed for her bedroom. Tania went to find Tanisha. Their families were vacationing together in a cottage in Gethia, a small town near Nainital. Their parents had rented out a quaint, three-bedroom, hill top cottage with a yard for a week in the middle of May. Tania's parents occupied the bedroom on the top floor of the cottage and baby Sonia slept with them. The room opened out to a large terrace, where Sonia enjoyed running around and playing with her cars and blocks. -

Trade Marks Journal No: 1809 , 07/08/2017 Class 35 3059367 21

Trade Marks Journal No: 1809 , 07/08/2017 Class 35 3059367 21/09/2015 BISHWAJIT KAR RENU KAR trading as ;ZAWHARAT 91, B.C. ROAD, OPPOSITE SURANA SILK HOUSE, BURDWAN, - 713101, WEST BENGAL. SERVICE PROVIDERS. A REGISTERED PARTNERSHIP CONCERN Used Since :01/07/2012 KOLKATA The bringing together, exhibition & display for the benefit of others, of a variety of precious and semi precious gem stones, diamond & gold jewellery, imitation jewellery through retail outlets, showrooms & stores including marketing, distribution, advertisement, import, export and retailing services related thereto 4801 Trade Marks Journal No: 1809 , 07/08/2017 Class 35 3061342 21/09/2015 MOHAMMED SALMAN trading as ;FANCY NEEDS 11-2-560, 1st Floor, Beside BSNL Telephone Exchange, Near Charkhandil, Aghapura, Hyderabad-500001, Telangana, India Sales & Service Provider Address for service in India/Attorney address: MADHUSUDAN PUTTA Prometheus Patent Services Pvt Ltd, Flat 201, Sairam Residency, Plot No. 116, 117 & 118, Alkapoor Township, Puppalaguda, Rajendra Nagar, Hyderabad-89. Used Since :31/08/2015 CHENNAI ADVERTISING; MARKETING, SALES, DISTRIBUTION, WHOLESALE, RETAIL & ONLINE RETAIL STORE SERVICES FEATURING ELECTRONIC PRODUCTS, FASHION CLOTHING APPAREL, FOOTWEAR, HEADGEAR, JEWELLERY, COSMETICS, WELLNESS PRODUCTS, HOME DECOR, FURNITURE, ART & GENERAL CONSUMER MERCHANDISE, COMPUTER PERIPHERALS & ACCESSORIES, MOBILES, ALL TYPES OF ACCESSORIES, HEAD PHONES & BATTERIES OF MOBILE PHONES & HAND HELD DEVICES, MUSIC, MOVIES, VIDEO GAMES, PERIODICALS AND OTHER MEDIA CONTENT, TOYS, GAMES, SPORTING GOODS, ELECTRONIC GAMES & VIDEO GAMES, GROCERIES, FOOD PRODUCTS & BEVERAGES. 4802 Trade Marks Journal No: 1809 , 07/08/2017 Class 35 3061343 21/09/2015 MOHAMMED SALMAN trading as ;FANCY NEEDS 11-2-560, 1st Floor, Beside BSNL Telephone Exchange, Near Charkhandil, Aghapura, Hyderabad-500001, Telangana, India Sales & Service Provider Address for service in India/Attorney address: MADHUSUDAN PUTTA Prometheus Patent Services Pvt Ltd, Flat 201, Sairam Residency, Plot No. -

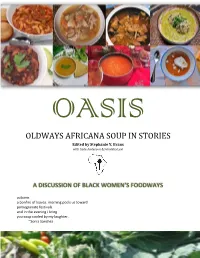

OLDWAYS AFRICANA SOUP in STORIES Edited by Stephanie Y

OASIS OLDWAYS AFRICANA SOUP IN STORIES Edited by Stephanie Y. Evans with Sade Anderson & Johnisha Levi A DISCUSSION OF BLACK WOMEN’S FOODWAYS autumn. a bonfire of leaves. morning peels us toward pomegranate festivals. and in the evening i bring you soup cooled by my laughter. ~Sonia Sanchez OASIS OLDWAYS AFRICANA SOUP IN STORIES “Cooking empowers us to choose what we want for ourselves and our families.” - Oldways, A Taste of African Heritage Cooking Program "Diabetes is not part of African-Americans' heritage. Neither is heart disease. What is in your heritage is a healthy heart, a strong body, extraordinary energy, vibrant and delicious foods, and a long healthy life." - Oldways, African Heritage and Health Program Oldways African Heritage & Health oldwayspt.org/programs/african-heritage-health Stephanie Y. Evans www.professorevans.net 2016 © Stephanie Y. Evans and Oldways Individual stories and recipes © contributors Header photo credit: Selas Kidane All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, printed, distributed, or transmitted in any form without written permission of the publisher. Electronic links to publication sources and not for profit sharing of complete publication document are encouraged. OASIS: Oldways Africana Soup in Stories is a collection of life stories and recipes. The publisher is not attempting to make any factual claims or offer health advice with content provided by contributing authors. The views and content expressed—and the recipes and photos in this work—are solely those of authors and do not reflect the views of the publisher; therefore, the publisher disclaims any responsibility held by authors. 1 Page A DISCUSSION OF BLACK WOMEN’S FOODWAYS OASIS gathers culturally-informed soup recipes to expand nutritional knowledge and discussions of Black women’s wellness. -

Traditional Food Board - a Necessity for India

Traditional Food Board - A Necessity for India 25 May 2016 | News | By Milind Kokje <p>Our body is made to digest and assimilate things which are available locally for you on regular basis. Import of any edible things may not be suitable for your body and may invite some trouble which may not be reflected in a short duration but may require generations to learn their ill effects. </p> Dr Prabodh S Halde, President, AFST(I) Mumbai Prof. Uday Annapure, HOD, ICT Mumbai Our body is made to digest and assimilate things which are available locally for you on regular basis. Import of any edible things may not be suitable for your body and may invite some trouble which may not be reflected in a short duration but may require generations to learn their ill effects. Therefore, we can see different food products at different locations all over the globe. Such special food products made by using locally available edible material has its own value for particular locality or even it may have therapeutic or medicinal benefits also. All such products are made by using wisdom and knowledge which is traditionally transferred from one generation to next hence these food products are known as traditional foods. Traditional food refers to foods consumed over the longterm duration of civilisation that have been passed through generations. Traditional foods and dishes may have a historic precedent in a national dish, regional cuisine or local cuisine. Traditional foods and beverages may be produced as homemade, by restaurants and small manufacturers, and by large food processing plant facilities. -

Using Image Fusion and Classification to Profile a Human Population; a Study in the Rural Region of Eastern India

USING IMAGE FUSION AND CLASSIFICATION TO PROFILE A HUMAN POPULATION; A STUDY IN THE RURAL REGION OF EASTERN INDIA Roberto Canavosio-Zuzelski George Mason University Dept. of Geography and Geoinformation Science Fairfax, Virginia [email protected] ABSTRACT With the recent advancements in image processing techniques and the increasing availability of high resolution satellite imagery, one has an increased ability to characterize human attributes. This paper will study the effects that image fusion has on the classification of Quickbird satellite imagery over a rural area in Eastern India. Two panchromatic sharpening algorithms will be used and compared to a classification of a single multispectral image to study the effects that image fusion has on image classification. Using the enhanced imagery an analysis into the prominent features like buildings, roads, agriculture, and water will be performed to characterize and better understand the human profile and lifestyle of the local population. Keywords: high resolution satellite imagery, fusion, classification, human profile INTRODUCTION This project was developed to bring a quantative analysis and human understanding to a particular region of interest in a third world country. For this project an area in Eastern India was chosen that is in the State of Orissa and contained in the Nayagarth and Khorda regions. High Resolution (HR) Quickbird panchromatic (PAN) and Multispectral (MS) images were used, along with, administrative layers depicting the state and regional boundaries in India. The image fusion portion of this project will attempt to answer the question of whether or not pan sharpening will improve the results of an image classification for roof pixels associated with dwellings in Eastern India. -

High Court of Delhi Advance Cause List

HIGH COURT OF DELHI ADVANCE CAUSE LIST LIST OF BUSINESS FOR WEDNESDAY,THE 01ST FEBRUARY,2012 INDEX PAGES 1. APPELLATE JURISDICTION 1 TO 46 2. COMPANY JURISDICTION 47 TO 48 3. ORIGINAL JURISDICTION 49 TO 60 4. REGISTRAR GENERAL / 61 TO 74 REGISTRAR (ORGL.) / REGISTRAR (ADMN.) / JOINT REGISTRARS (ORGL.) 01.02.2012 1 (APPELLATE JURISDICTION) 01.02.2012 [Note : Unless otherwise specified, before all appellate side courts, fresh matters shown in the supplementary lists will be taken up first.] COURT NO. 1 (DIVISION BENCH-1) HON'BLE THE ACTING CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE RAJIV SAHAI ENDLAW [NOTE: NO PASSOVER SHALL BE GIVEN IN THE FIRST TEN MATTERS.] FRESH MATTERS & APPLICATIONS ______________________________ 1. CHAT.A.REF 6/2011 COUNCIL OF INSTITUTE OF RAKESH AGARWAL CHARTERED ACCOUNTANTS OF INDIA Vs. SANJEEV SHARMA 2. LPA 882/2011 MANAGEMENT MUNICIPAL CORP OF MADHU TEWATIA CM APPL. 19611/2011 DELHI Vs. WORKMEN THR GENERAL MAZDOOR UNION 3. LPA 1071/2011 MANAGEMENT OF KERALA HOUSE R SATHISH CM APPL. 23083/2011 Vs. SANJAY KUMAR AND ANR 4. W.P.(C) 299/2012 COURT ON ITS OWN MOTION THROGH LETTER Vs. MUNICIPAL CORPORATION OF DELHI AND ANR AFTER NOTICE MISC. MATTERS 5. CHAT.A.REF 5/2011 COUNCIL OF THE INSTT OF RAKESH AGGARWAL CHARTERED ACCOUNTANTS OF INDIA Vs. RAKESH VERMA AND ANR 6. FAO(OS) 486/2001 MOHAN LAL HARBANSLAL BHAYANA SACHIN DUTTA,PRIYA KUMAR AND Vs. UOI 7. LPA 244/2008 MASOOM FOUNDATION (REGD. NGO) MALINI SUD,L.K.GARG,DEEPAK CM APPL. 8203/2008 Vs. U.O.I AND ORS KHURANA,JATAN SINGH,RAJIV CM APPL. -

01 Cuisines of Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Kerala

Regional Cuisines of India –II BHM-602AT UNIT: 01 CUISINES OF ANDHRA PRADESH, TAMIL NADU AND KERALA STRUCTURE 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Objectives 1.3 Andhra Pradesh 1.3.1 Geographical perspectives 1.3.2 Brief historical background 1.3.3 Culture and traditions of the people of Andhra Pradesh 1.3.4 Climate 1.3.5 Agriculture and staple food 1.3.6 Characteristics & salient features of cuisine 1.3.7 Equipments and utensils used 1.3.8 Specialties during festivals and other occasions 1.3.9 Festivals and other occasions 1.3.10 Community foods 1.3.11 Dishes from Andhra Pradesh cuisine 1.4 Tamil Nadu 1.4.1 Geographical perspectives 1.4.2 Brief historical background 1.4.3 Culture and Traditions of the people of Tamil Nadu 1.4.4 Climate 1.4.5 Agriculture and staple food 1.4.6 Characteristics and Salient features of the cuisine 1.4.7 Equipments and Utensils Used 1.4.8 Specialties during festivals and other occasions 1.4.9 Festivals and other occasions 1.4.10 Dishes from Tamil Nadu Cuisine 1.5 Kerala 1.5.1 Geographical perspectives 1.5.2 Brief historical background 1.5.3 Climate 1.5.4 Agriculture, staple food and social life 1.5.5 Characteristics and salient features of the cuisine 1.5.6 Popular foods and specialties 1.5.7 Specialties during festivals and other occasions 1.5.8 Festivals and other occasions 1.5.9 Dishes from Kerala cuisine 1.6 Summary 1.7 Glossary 1.8 Reference/Bibliography 1.9 Terminal Questions Uttarakhand Open University 1 Regional Cuisines of India –II BHM-602AT 1.1 INTRODUCTION Andhra Pradesh is one of the south Indian states and is positioned in the coastal area towards the south eastern part of the country and because of its location in the merging area of the Deccan plateau and the coastal plains and also transverse by Krishna and Godavari rivers, the state experiences varied physical features.