SLA0403 05 Book Reviews 346..366

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2009 The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M. Stockins University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Stockins, Jennifer M., The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney, Master of Arts - Research thesis, University of Wollongong. School of Art and Design, University of Wollongong, 2009. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ theses/3164 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree Master of Arts - Research (MA-Res) UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG Jennifer M. Stockins, BCA (Hons) Faculty of Creative Arts, School of Art and Design 2009 ii Stockins Statement of Declaration I certify that this thesis has not been submitted for a degree to any other university or institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by any other person, except where due reference has been made in the text. Jennifer M. Stockins iii Stockins Abstract Manga (Japanese comic books), Anime (Japanese animation) and Superflat (the contemporary art by movement created Takashi Murakami) all share a common ancestry in the woodblock prints of the Edo period, which were once mass-produced as a form of entertainment. -

Letters and Gifts in Early Medieval China

Material and Symbolic Economies: Letters and Gifts in Early Medieval China The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Tian, Xiaofei. "4 Material and Symbolic Economies: Letters and Gifts in Early Medieval China." In A History of Chinese Letters and Epistolary Culture, pp. 135-186. Brill, 2015. Published Version doi:10.1163/9789004292123_006 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:29037391 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP Material and Symbolic Economies_Tian Material and Symbolic Economies: Letters and Gifts in Early Medieval China* Xiaofei Tian Harvard University This paper examines a group of letters in early medieval China, specifically from the turn of the third century and from the early sixth century, about gift giving and receiving. Gift-giving is one of the things that stand at the center of social relationships across many cultures. “The gift imposes an identity upon the giver as well as the receiver.”1 It is both productive of social relationships and affirms them; it establishes and clarifies social status, displays power, strengthens alliances, and creates debt and obligations. This was particularly true in the chaotic period following the collapse of the Han empire at the turn of the third century, often referred to by the reign title of the last Han emperor as the Jian’an 建安 era (196-220). -

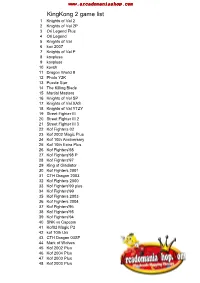

Kingkong 2 Game List

www.arcadomaniashop.com KingKong 2 game list 1 Knights of Val 2 2 Knights of Val 2P 3 Ori Legend Plus 4 Ori Legend 5 Knights of Val 6 kov 2007 7 Knights of Val P 8 kovplusa 9 kovpluss 10 kovsh 11 Dragon World II 12 Photo Y2K 13 Puzzle Star 14 The Killing Blade 15 Martial Masters 16 Knights of Val SP 17 Knights of Val XAS 18 Knights of Val YTZY 19 Street Fighter III 20 Street Fighter III 2 21 Street Fighter III 3 22 Kof Fighters 02 23 Kof 2002 Magic Plus 24 Kof 10th Anniversary 25 Kof 10th Extra Plus 26 Kof Fighters'98 27 Kof Fighters'98 P 28 Kof Fighters'97 29 King of Gladiator 30 Kof Fighters 2001 31 CTH Dragon 2003 32 Kof Fighters 2000 33 Kof Fighters'99 plus 34 Kof Fighters'99 35 Kof Fighters 2003 36 Kof Fighters 2004 37 Kof Fighters'96 38 Kof Fighters'95 39 Kof Fighters'94 40 SNK vs Capcom 41 Kof02 Magic P2 42 kof 10th Uni 43 CTH Dragon 03SP 44 Mark of Wolves 45 Kof 2002 Plus 46 Kof 2004 Plus 47 Kof 2003 Plus 48 Kof 2000 Plus www.arcadomaniashop.com 49 Kof 2001 Plus 50 Kof 2003 Hero 51 DoubleDragon Plus 52 Kof 95 Plus 53 Kof 96 Plus 54 Kof 97 Plus 55 Metal Slug 56 Metal Slug 2 57 Metal Slug 3 58 Metal Slug 4 59 Metal Slug 5 60 Metal Slug 6 61 Metal Slug x 62 Metal Slug Plus 63 Metal Slug 2 Plus 64 Metal Slug 3 Plus 65 Metal Slug 4 Plus 66 Metal Slug 5 Plus 67 Metal Slug 6 Plus 68 1941 69 Cadillacs & Dino 70 Cadillacs & Dino 2 71 Captain Commando 72 Knights of Round 73 Knights of Round SH 74 Mega Twins 75 The king of Dragons 76 punisher 77 San Jian Sheng 78 Warriors of Fate 79 Three Wonders 80 Sangokushi II 81 Dynasty Wars 82 Magic -

International Reinterpretations

International Reinterpretations 1 Remakes know no borders… 2 … naturally, this applies to anime and manga as well. 3 Shogun Warriors 4 Stock-footage series 5 Non-US stock-footage shows Super Riders with the Devil Hanuman and the 5 Riders 6 OEL manga 7 OEL manga 8 OEL manga 9 Holy cow, more OEL manga! 10 Crossovers 11 Ghost Rider? 12 The Lion King? 13 Godzilla 14 Guyver 15 Crying Freeman 16 Fist of the North Star 17 G-Saviour 18 Blood: the Last Vampire 19 Speed Racer 20 Imagi Studios 21 Ultraman 6 Brothers vs. the Monster Army (Thailand) The Adventure Begins (USA) Towards the Future (Australia) The Ultimate Hero (USA) Tiga manhwa 22 Dragonball 23 Wicked City 24 City Hunter 25 Initial D 26 Riki-Oh 27 Asian TV Dramas Honey and Clover Peach Girl (Taiwan) Prince of Tennis (Taiwan) (China) 28 Boys Over Flowers Marmalade Boy (Taiwan) (South Korea) Oldboy 29 Taekwon V 30 Super Batman and Mazinger V 31 Space Gundam? Astro Plan? 32 Journey to the West (Saiyuki) Alakazam the Great Gensomaden Saiyuki Monkey Typhoon Patalliro Saiyuki Starzinger Dragonball 33 More “Goku”s 34 The Water Margin (Suikoden) Giant Robo Outlaw Star Suikoden Demon Century Akaboshi 35 Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Sangokushi) Mitsuteru Yokoyama’s Sangokushi Kotetsu Sangokushi BB Senshi Sangokuden Koihime Musou Ikkitousen 36 World Masterpiece Theater (23 seasons since 1969) Moomin Heidi A Dog of Flanders 3000 Leagues in Search of Mother Anne of Green Gables Adventures of Tom Sawyer Swiss Family Robinson Little Women Little Lord Fauntleroy Peter -

How Poetry Became Meditation in Late-Ninth-Century China

how poetry became meditation Asia Major (2019) 3d ser. Vol. 32.2: 113-151 thomas j. mazanec How Poetry Became Meditation in Late-Ninth-Century China abstract: In late-ninth-century China, poetry and meditation became equated — not just meta- phorically, but as two equally valid means of achieving stillness and insight. This article discusses how several strands in literary and Buddhist discourses fed into an assertion about such a unity by the poet-monk Qiji 齊己 (864–937?). One strand was the aesthetic of kuyin 苦吟 (“bitter intoning”), which involved intense devotion to poetry to the point of suffering. At stake too was the poet as “fashioner” — one who helps make and shape a microcosm that mirrors the impersonal natural forces of the macrocosm. Jia Dao 賈島 (779–843) was crucial in popularizing this sense of kuyin. Concurrently, an older layer of the literary-theoretical tradition, which saw the poet’s spirit as roaming the cosmos, was also given new life in late Tang and mixed with kuyin and Buddhist meditation. This led to the assertion that poetry and meditation were two gates to the same goal, with Qiji and others turning poetry writing into the pursuit of enlightenment. keywords: Buddhism, meditation, poetry, Tang dynasty ometime in the early-tenth century, not long after the great Tang S dynasty 唐 (618–907) collapsed and the land fell under the control of regional strongmen, a Buddhist monk named Qichan 棲蟾 wrote a poem to another monk. The first line reads: “Poetry is meditation for Confucians 詩為儒者禪.”1 The line makes a curious claim: the practice Thomas Mazanec, Dept. -

East Asian Languages & Civilization (EALC)

East Asian Languages & Civilization (EALC) 1 EALC 008 East Asian Religions EAST ASIAN LANGUAGES & This course will introduce students to the diverse beliefs, ideas, and practices of East Asia's major religious traditions: Buddhism, CIVILIZATION (EALC) Confucianism, Daoism, Shinto, Popular Religion, as well as Asian forms of Islam and Christianity. As religious identity in East Asia is often EALC 001 Introduction to Chinese Civilization fluid and non-sectarian in nature, there religious traditions will not be Survey of the civilization of China from prehistoric times to the present. investigated in isolation. Instead, the course will adopt a chronological For BA Students: History and Tradition Sector and geographical approach, examining the spread of religious ideas and Taught by: Goldin, Atwood, Smith, Cheng practices across East Asia and the ensuing results of these encounters. Course usually offered in fall term The course will be divided into three units. Unit one will cover the Activity: Lecture religions of China. We will begin by discussing early Chinese religion 1.0 Course Unit and its role in shaping the imperial state before turning to the arrival EALC 002 Introduction to Japanese Civilization of Buddhism and its impact in the development of organized Daoism, Survey of the civilization of Japan from prehistoric times to the present. as well as local religion. In the second unit, we will turn eastward into For BA Students: History and Tradition Sector Korea and Japan. After examining the impact of Confucianism and Course usually offered in spring term Buddhism on the religious histories of these two regions, we will proceed Activity: Lecture to learn about the formation of new schools of Buddhism, as well as 1.0 Course Unit the rituals and beliefs associated with Japanese Shinto and Korean Notes: Fulfills Cross-Cultural Analysis Shamanism. -

Pcbs : King Kong 2 500-In-1

PCBs : King Kong 2 500-in-1 King Kong 2 500-in-1 Rating: Not Rated Yet Price: Sales price: $129.95 Discount: Ask a question about this product Description GAME LIST Knights of Valour 2 Knights of Valour 2 plus Oriental Legend Plus Oriental Legend Knights of Valour kov 2007 Knights of Valour plus kovplusa kovpluss kovsh 1 / 5 PCBs : King Kong 2 500-in-1 Dragon World II Photo Y2K Puzzle Star The Killing Blade Martial Masters Knights of Valour SP Knights of Valour XAS Knights of Valour YTZY Knights of Valour QHSG Demon Front Dragon World 2001 Dragon World Pretty Chance Street Fighter III Street Fighter III 2 Street Fighter III 3 King of Fighters 2002 Kof 2002 Magic Plus Kof 10th Anniversary Kof 10th Extra Plus King of Fighters '98 King of Fighters '98 plus King of Fighters '97 King of Gladiator King of Fighters 2001 CTH Dragon 2003 King of Fighters 2000 Kof Fighters '99 plus King of Fighters '99 King of Fighters 2003 King of Fighters 2004 King of Fighters '96 2 / 5 PCBs : King Kong 2 500-in-1 King of Fighters '95 King of Fighters '94 SNK vs Capcom Kof2002 Magic Plus 2 Kof10th 2005 Unique CTH Dragon 2003 SP Mark of the Wolves Kof2002 Plus Kof 2004 Plus Kof 2003 Plus Kof 2000 Plus Kof 2001 Plus Kof 2003 Hero Double Dragon Plus Kof 95 Plus Kof 96 Plus Kof 97 Plus Metal Slug Metal Slug 2 Metal Slug 3 Metal Slug 4 Metal Slug 5 Metal Slug 6 Metal Slug x Metal Slug Plus Metal Slug 2 Plus Metal Slug 3 Plus Metal Slug 4 Plus Metal Slug 5 Plus Metal Slug 6 Plus 1941 3 / 5 PCBs : King Kong 2 500-in-1 Cadillacs & Dinosaurs Cadillacs&Dinosaurs2 Captain -

The Transparent Stone

WU HUNG The TransparentStone: Inverted Vision and Binary Imagery in Medieval Chinese Art A CRUCIAL MOMENT DIVIDES the course of Chinese art into two broad periods. Before this moment,a ritual art traditiontransformed general political and religious concepts into material symbols.Forms that we now call worksof art were integralparts of largermonumental complexes such as temples and tombs,and theircreators were anonymouscraftsmen whose individualcrea- tivitywas generallysubordinated to largercultural conventions. From the fourth and fifthcenturies on, however,there appeared a group of individuals-scholar- artistsand art critics-who began to forge theirown history.Although the con- structionof religiousand politicalmonuments never stopped, these men of let- ters attempted to transformpublic art into their private possessions, either physically,artistically, or spiritually.They developed a strongsentiment toward ruins,accumulated collectionsof antiques,placed miniaturemonuments in their houses and gardens,and "refined"common calligraphicand pictorialidioms into individual styles.This paper discusses new modes of writingand paintingat this liminalpoint in Chinese art history. Reversed Image and Inverted Vision Near the modern cityof Nanjing in eastern China, some ten mauso- leums survivingfrom the early sixth centurybear witnessto the past glory of emperors and princes of the Liang Dynasty(502-57).' The mausoleums share a general design (fig. 1). Three pairs of stone monumentsare usually erected in frontof the tumulus: a pair of stone animals-lions or qilinunicorns according to the statusof the dead-are placed before a gate formedby two stone pillars; the name and titleof the deceased appear on the flatpanels beneath the pillars' capitals. Finallytwo opposing memorialstelae bear identicalepitaphs recording the career and meritsof the dead person. -

3390 in 1 Games List

3390 in 1 Games List www.arcademultigamesales.co.uk Game Name Tekken 3 Tekken 2 Tekken Street Fighter Alpha 3 Street Fighter EX Bloody Roar 2 Mortal Kombat 4 Mortal Kombat 3 Mortal Kombat 2 Gear Fighter Dendoh Shiritsu Justice gakuen Turtledove (Chinese version) Super Capability War 2012 (US Edition) Tigger's Honey Hunt(U) Batman Beyond - Return of the Joker Bio F.R.E.A.K.S. Dual Heroes Killer Instinct Gold Mace - The Dark Age War Gods WWF Attitude Tom and Jerry in Fists of Furry 1080 Snowboarding Big Mountain 2000 Air Boarder 64 Tony Hawk's Pro Skater Aero Gauge Carmageddon 64 Choro Q 64 Automobili Lamborghini Extreme-G Jeremy McGrath Supercross 2000 Mario Kart 64 San Francisco Rush - Extreme Racing V-Rally Edition 99 Wave Race 64 Wipeout 64 All Star Tennis '99 Centre Court Tennis Virtual Pool 64 NBA Live 99 Castlevania Castlevania: Legacy of 1 Darkness Army Men - Sarge's Heroes Blues Brothers 2000 Bomberman Hero Buck Bumble Bug's Life,A Bust A Move '99 Chameleon Twist Chameleon Twist 2 Doraemon 2 - Nobita to Hikari no Shinden Gex 3 - Deep Cover Gecko Ms. Pac-Man Maze Madness O.D.T (Or Die Trying) Paperboy Rampage 2 - Universal Tour Super Mario 64 Toy Story 2 Aidyn Chronicles Charlie Blast's Territory Perfect Dark Star Fox 64 Star Soldier - Vanishing Earth Tsumi to Batsu - Hoshi no Keishousha Asteroids Hyper 64 Donkey Kong 64 Banjo-Kazooie The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time The King of Fighters '97 Practice The King of Fighters '98 Practice The King of Fighters '98 Combo Practice The King of Fighters -

A History of Chinese Letters and Epistolary Culture

A History of Chinese Letters and Epistolary Culture Edited by Antje Richter LEIDEN | BOSTON For use by the Author only | © 2015 Koninklijke Brill NV Contents Acknowledgements ix List of Illustrations xi Abbreviations xiii About the Contributors xiv Introduction: The Study of Chinese Letters and Epistolary Culture 1 Antje Richter PART 1 Material Aspects of Chinese Letter Writing Culture 1 Reconstructing the Postal Relay System of the Han Period 17 Y. Edmund Lien 2 Letters as Calligraphy Exemplars: The Long and Eventful Life of Yan Zhenqing’s (709–785) Imperial Commissioner Liu Letter 53 Amy McNair 3 Chinese Decorated Letter Papers 97 Suzanne E. Wright 4 Material and Symbolic Economies: Letters and Gifts in Early Medieval China 135 Xiaofei Tian PART 2 Contemplating the Genre 5 Letters in the Wen xuan 189 David R. Knechtges 6 Between Letter and Testament: Letters of Familial Admonition in Han and Six Dynasties China 239 Antje Richter For use by the Author only | © 2015 Koninklijke Brill NV vi Contents 7 The Space of Separation: The Early Medieval Tradition of Four-Syllable “Presentation and Response” Poetry 276 Zeb Raft 8 Letters and Memorials in the Early Third Century: The Case of Cao Zhi 307 Robert Joe Cutter 9 Liu Xie’s Institutional Mind: Letters, Administrative Documents, and Political Imagination in Fifth- and Sixth-Century China 331 Pablo Ariel Blitstein 10 Bureaucratic Influences on Letters in Middle Period China: Observations from Manuscript Letters and Literati Discourse 363 Lik Hang Tsui PART 3 Diversity of Content and Style section 1 Informal Letters 11 Private Letter Manuscripts from Early Imperial China 403 Enno Giele 12 Su Shi’s Informal Letters in Literature and Life 475 Ronald Egan 13 The Letter as Artifact of Sentiment and Legal Evidence 508 Janet Theiss 14 Infijinite Variations of Writing and Desire: Love Letters in China and Europe 546 Bonnie S. -

Three Kingdoms 1St Edition Kindle

THREE KINGDOMS 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Guanzhong Luo | 9780520957879 | | | | | Three Kingdoms 1st edition PDF Book Num Pages: pages. While the novel follows hundreds of characters, the focus is mainly on the three power blocs that emerged f I want to recommend a special book named Three Kingdoms of Romance to everybody,if you like reading books,I am pretty sure you will like this. More filters. It's something that shows up in jokes, political thinking, and popular culture. About Luo Guanzhong. Condition: Very Good. About this Item: I want to recommend a special book named Three Kingdoms of Romance to everybody,if you like reading books,I am pretty sure you will like this. Condition: New. Pictorial Soft Cover. Error rating book. The footnotes add a lot for anyone who doesn't know the history. More information about this seller Contact this seller 4. Solid and clean. Taidang rated it really liked it Mar 07, Seller Inventory ABE Average rating 4. Very entertaining as a story, and occasionally moving as parable. Because this is a long-story book,I think the people who have patient and like the history of Three Kingdoms period will love this book. Create a Want BookSleuth Can't remember the title or the author of a book? Dimension: x x The University of California Press is pleased to make the complete and unabridged translation available again. Must read for any fan of chinese history. More information about this seller Contact this seller The book is challenging in more than a few ways. That was nuts. -

Chinese Foreign Aromatics Importation

CHINESE FOREIGN AROMATICS IMPORTATION FROM THE 2ND CENTURY BCE TO THE 10TH CENTURY CE Research Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with research distinction in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University. by Shiyong Lu The Ohio State University April 2019 Project Advisor: Professor Scott Levi, Department of History 1 Introduction Trade served as a major form of communication between ancient civilizations. Goods as well as religions, art, technology and all kinds of knowledge were exchanged throughout trade routes. Chinese scholars traditionally attribute the beginning of foreign trade in China to Zhang Qian, the greatest second century Chinese diplomat who gave China access to Central Asia and the world. Trade routes on land between China and the West, later known as the Silk Road, have remained a popular topic among historians ever since. In recent years, new archaeological evidences show that merchants in Southern China started to trade with foreign countries through sea routes long before Zhang Qian’s mission, which raises scholars’ interests in Maritime Silk Road. Whether doing research on land trade or on maritime trade, few scholars concentrate on the role of imported aromatics in Chinese trade, which can be explained by several reasons. First, unlike porcelains or jewelry, aromatics are not durable. They were typically consumed by being burned or used in medicine, perfume, cooking, etc. They might have been buried in tombs, but as organic matters they are hard to preserve. Lack of physical evidence not only leads scholars to generally ignore aromatics, but also makes it difficult for those who want to do further research.