Japanese Console Games Popularization in China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2009 The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M. Stockins University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Stockins, Jennifer M., The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney, Master of Arts - Research thesis, University of Wollongong. School of Art and Design, University of Wollongong, 2009. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ theses/3164 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree Master of Arts - Research (MA-Res) UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG Jennifer M. Stockins, BCA (Hons) Faculty of Creative Arts, School of Art and Design 2009 ii Stockins Statement of Declaration I certify that this thesis has not been submitted for a degree to any other university or institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by any other person, except where due reference has been made in the text. Jennifer M. Stockins iii Stockins Abstract Manga (Japanese comic books), Anime (Japanese animation) and Superflat (the contemporary art by movement created Takashi Murakami) all share a common ancestry in the woodblock prints of the Edo period, which were once mass-produced as a form of entertainment. -

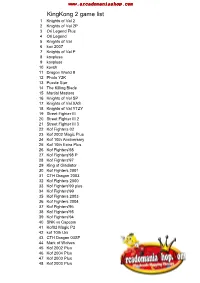

Kingkong 2 Game List

www.arcadomaniashop.com KingKong 2 game list 1 Knights of Val 2 2 Knights of Val 2P 3 Ori Legend Plus 4 Ori Legend 5 Knights of Val 6 kov 2007 7 Knights of Val P 8 kovplusa 9 kovpluss 10 kovsh 11 Dragon World II 12 Photo Y2K 13 Puzzle Star 14 The Killing Blade 15 Martial Masters 16 Knights of Val SP 17 Knights of Val XAS 18 Knights of Val YTZY 19 Street Fighter III 20 Street Fighter III 2 21 Street Fighter III 3 22 Kof Fighters 02 23 Kof 2002 Magic Plus 24 Kof 10th Anniversary 25 Kof 10th Extra Plus 26 Kof Fighters'98 27 Kof Fighters'98 P 28 Kof Fighters'97 29 King of Gladiator 30 Kof Fighters 2001 31 CTH Dragon 2003 32 Kof Fighters 2000 33 Kof Fighters'99 plus 34 Kof Fighters'99 35 Kof Fighters 2003 36 Kof Fighters 2004 37 Kof Fighters'96 38 Kof Fighters'95 39 Kof Fighters'94 40 SNK vs Capcom 41 Kof02 Magic P2 42 kof 10th Uni 43 CTH Dragon 03SP 44 Mark of Wolves 45 Kof 2002 Plus 46 Kof 2004 Plus 47 Kof 2003 Plus 48 Kof 2000 Plus www.arcadomaniashop.com 49 Kof 2001 Plus 50 Kof 2003 Hero 51 DoubleDragon Plus 52 Kof 95 Plus 53 Kof 96 Plus 54 Kof 97 Plus 55 Metal Slug 56 Metal Slug 2 57 Metal Slug 3 58 Metal Slug 4 59 Metal Slug 5 60 Metal Slug 6 61 Metal Slug x 62 Metal Slug Plus 63 Metal Slug 2 Plus 64 Metal Slug 3 Plus 65 Metal Slug 4 Plus 66 Metal Slug 5 Plus 67 Metal Slug 6 Plus 68 1941 69 Cadillacs & Dino 70 Cadillacs & Dino 2 71 Captain Commando 72 Knights of Round 73 Knights of Round SH 74 Mega Twins 75 The king of Dragons 76 punisher 77 San Jian Sheng 78 Warriors of Fate 79 Three Wonders 80 Sangokushi II 81 Dynasty Wars 82 Magic -

International Reinterpretations

International Reinterpretations 1 Remakes know no borders… 2 … naturally, this applies to anime and manga as well. 3 Shogun Warriors 4 Stock-footage series 5 Non-US stock-footage shows Super Riders with the Devil Hanuman and the 5 Riders 6 OEL manga 7 OEL manga 8 OEL manga 9 Holy cow, more OEL manga! 10 Crossovers 11 Ghost Rider? 12 The Lion King? 13 Godzilla 14 Guyver 15 Crying Freeman 16 Fist of the North Star 17 G-Saviour 18 Blood: the Last Vampire 19 Speed Racer 20 Imagi Studios 21 Ultraman 6 Brothers vs. the Monster Army (Thailand) The Adventure Begins (USA) Towards the Future (Australia) The Ultimate Hero (USA) Tiga manhwa 22 Dragonball 23 Wicked City 24 City Hunter 25 Initial D 26 Riki-Oh 27 Asian TV Dramas Honey and Clover Peach Girl (Taiwan) Prince of Tennis (Taiwan) (China) 28 Boys Over Flowers Marmalade Boy (Taiwan) (South Korea) Oldboy 29 Taekwon V 30 Super Batman and Mazinger V 31 Space Gundam? Astro Plan? 32 Journey to the West (Saiyuki) Alakazam the Great Gensomaden Saiyuki Monkey Typhoon Patalliro Saiyuki Starzinger Dragonball 33 More “Goku”s 34 The Water Margin (Suikoden) Giant Robo Outlaw Star Suikoden Demon Century Akaboshi 35 Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Sangokushi) Mitsuteru Yokoyama’s Sangokushi Kotetsu Sangokushi BB Senshi Sangokuden Koihime Musou Ikkitousen 36 World Masterpiece Theater (23 seasons since 1969) Moomin Heidi A Dog of Flanders 3000 Leagues in Search of Mother Anne of Green Gables Adventures of Tom Sawyer Swiss Family Robinson Little Women Little Lord Fauntleroy Peter -

Pcbs : King Kong 2 500-In-1

PCBs : King Kong 2 500-in-1 King Kong 2 500-in-1 Rating: Not Rated Yet Price: Sales price: $129.95 Discount: Ask a question about this product Description GAME LIST Knights of Valour 2 Knights of Valour 2 plus Oriental Legend Plus Oriental Legend Knights of Valour kov 2007 Knights of Valour plus kovplusa kovpluss kovsh 1 / 5 PCBs : King Kong 2 500-in-1 Dragon World II Photo Y2K Puzzle Star The Killing Blade Martial Masters Knights of Valour SP Knights of Valour XAS Knights of Valour YTZY Knights of Valour QHSG Demon Front Dragon World 2001 Dragon World Pretty Chance Street Fighter III Street Fighter III 2 Street Fighter III 3 King of Fighters 2002 Kof 2002 Magic Plus Kof 10th Anniversary Kof 10th Extra Plus King of Fighters '98 King of Fighters '98 plus King of Fighters '97 King of Gladiator King of Fighters 2001 CTH Dragon 2003 King of Fighters 2000 Kof Fighters '99 plus King of Fighters '99 King of Fighters 2003 King of Fighters 2004 King of Fighters '96 2 / 5 PCBs : King Kong 2 500-in-1 King of Fighters '95 King of Fighters '94 SNK vs Capcom Kof2002 Magic Plus 2 Kof10th 2005 Unique CTH Dragon 2003 SP Mark of the Wolves Kof2002 Plus Kof 2004 Plus Kof 2003 Plus Kof 2000 Plus Kof 2001 Plus Kof 2003 Hero Double Dragon Plus Kof 95 Plus Kof 96 Plus Kof 97 Plus Metal Slug Metal Slug 2 Metal Slug 3 Metal Slug 4 Metal Slug 5 Metal Slug 6 Metal Slug x Metal Slug Plus Metal Slug 2 Plus Metal Slug 3 Plus Metal Slug 4 Plus Metal Slug 5 Plus Metal Slug 6 Plus 1941 3 / 5 PCBs : King Kong 2 500-in-1 Cadillacs & Dinosaurs Cadillacs&Dinosaurs2 Captain -

3390 in 1 Games List

3390 in 1 Games List www.arcademultigamesales.co.uk Game Name Tekken 3 Tekken 2 Tekken Street Fighter Alpha 3 Street Fighter EX Bloody Roar 2 Mortal Kombat 4 Mortal Kombat 3 Mortal Kombat 2 Gear Fighter Dendoh Shiritsu Justice gakuen Turtledove (Chinese version) Super Capability War 2012 (US Edition) Tigger's Honey Hunt(U) Batman Beyond - Return of the Joker Bio F.R.E.A.K.S. Dual Heroes Killer Instinct Gold Mace - The Dark Age War Gods WWF Attitude Tom and Jerry in Fists of Furry 1080 Snowboarding Big Mountain 2000 Air Boarder 64 Tony Hawk's Pro Skater Aero Gauge Carmageddon 64 Choro Q 64 Automobili Lamborghini Extreme-G Jeremy McGrath Supercross 2000 Mario Kart 64 San Francisco Rush - Extreme Racing V-Rally Edition 99 Wave Race 64 Wipeout 64 All Star Tennis '99 Centre Court Tennis Virtual Pool 64 NBA Live 99 Castlevania Castlevania: Legacy of 1 Darkness Army Men - Sarge's Heroes Blues Brothers 2000 Bomberman Hero Buck Bumble Bug's Life,A Bust A Move '99 Chameleon Twist Chameleon Twist 2 Doraemon 2 - Nobita to Hikari no Shinden Gex 3 - Deep Cover Gecko Ms. Pac-Man Maze Madness O.D.T (Or Die Trying) Paperboy Rampage 2 - Universal Tour Super Mario 64 Toy Story 2 Aidyn Chronicles Charlie Blast's Territory Perfect Dark Star Fox 64 Star Soldier - Vanishing Earth Tsumi to Batsu - Hoshi no Keishousha Asteroids Hyper 64 Donkey Kong 64 Banjo-Kazooie The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time The King of Fighters '97 Practice The King of Fighters '98 Practice The King of Fighters '98 Combo Practice The King of Fighters -

Three Kingdoms 1St Edition Kindle

THREE KINGDOMS 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Guanzhong Luo | 9780520957879 | | | | | Three Kingdoms 1st edition PDF Book Num Pages: pages. While the novel follows hundreds of characters, the focus is mainly on the three power blocs that emerged f I want to recommend a special book named Three Kingdoms of Romance to everybody,if you like reading books,I am pretty sure you will like this. More filters. It's something that shows up in jokes, political thinking, and popular culture. About Luo Guanzhong. Condition: Very Good. About this Item: I want to recommend a special book named Three Kingdoms of Romance to everybody,if you like reading books,I am pretty sure you will like this. Condition: New. Pictorial Soft Cover. Error rating book. The footnotes add a lot for anyone who doesn't know the history. More information about this seller Contact this seller 4. Solid and clean. Taidang rated it really liked it Mar 07, Seller Inventory ABE Average rating 4. Very entertaining as a story, and occasionally moving as parable. Because this is a long-story book,I think the people who have patient and like the history of Three Kingdoms period will love this book. Create a Want BookSleuth Can't remember the title or the author of a book? Dimension: x x The University of California Press is pleased to make the complete and unabridged translation available again. Must read for any fan of chinese history. More information about this seller Contact this seller The book is challenging in more than a few ways. That was nuts. -

Kyokutei Bakin's Eight Dogs and Chinese Vernacular Novels By

Kyokutei Bakin’s Eight Dogs and Chinese Vernacular Novels by Shan Ren A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of East Asian Studies University of Alberta © Shan Ren, 2019 ABSTRACT Kyokutei Bakin’s 曲亭馬琴 (1767-1848) magnum opus Nansō Satomi Hakkenden 南総里見八犬伝 (The Chronicle of the Eight Dogs of the Nansō Satomi Clan; hereafter, Eight Dogs, 1814-42) had been long overlooked by both Japanese and Western academia. Although Eight Dogs has recently received more attention, most scholars still hold an oversimplified view of its relationship with Chinese vernacular novels. They believe that the large number of Chinese fictional narratives Bakin incorporated in Eight Dogs can be divided into two parts: Shuihu zhuan 水滸傳 (J. Suikoden; Water Margin) and everything else. This claim seems to be plausible because Bakin was indeed obsessed with Water Margin and he did use Water Margin as one of the main sources for Eight Dogs. However, this claim overlooks the possibility of the existence of other Chinese sources which also strongly influenced the composition of Eight Dogs. This research aims to investigate this possiblity of other important Chinese sources and Bakin’s motive and purpose in basing Eight Dogs on Chinese vernacular novels. In order to discuss Bakin’s use of Chinese vernacular novels in Eight Dogs, it is first and foremost important to identify all the crucial Chinese sources for Eight Dogs. Chapter One lays out Eight Dogs’ three main story lines and its three groups of main characters, among which one story line and a group of main characters match those of Water Margin, and the other two pairs match those of Sanguozhi yanyi 三國志演義 (J. -

Westphalian IR and Romance of the Three Kingdoms

Romancing Westphalia: Westphalian IR and Romance of the Three Kingdoms L.H.M. LING* Abstract Introduction We need to re-envision international relations State violence in Asia invariably (IR). By framing world politics as a world-of- resurrects the West’s old saw about worlds comprised of multiple, interactive and 1 overlapping regional worlds, we can curb the “Oriental despotism”. Basically, it hegemony of the West through Westphalian IR accuses “Oriental” peoples of not and stem, if not transform, the “cartographic knowing how to govern themselves. anxieties” that still beset postcolonial states. Both They resort to acts of violence and of these provoke state violence externally and suppression whenever dissent arises, internally. This paper examines an East Asian regional world inflected by the 14th-century Eurocentrics claim, in contrast to the Chinese epic, Romance of the Three Kingdoms. enlightened, democratic processes of the Noting its conflicts as well as compatibilities West. It’s the same old story of the future with Westphalian IR, I conclude with the vs the past, modernity vs tradition, implications of this thought experiment for IR liberal-democracy vs authoritarianism. and for world politics in general. To Fukuyama, this realisation signals “the end of history”.2 They (“the Orient”) Key Words must learn to be more like us (“the West”). Accordingly, more education, Regional worlds, hegemony, conflict and compatibility, Westphalian IR, Romance of more supervision and, if necessary, more the Three Kingdoms. sanctions must follow. The West still rules. * L.H.M. Ling is Associate Dean of Faculty Affairs at the New School for Public Besides its inherent imperialism, this Engagement (NSPE) and Associate Professor Eurocentric critique sees only half the at the Milano School of International Affairs, picture. -

1 Tekken 6 2 Tekken 5 3 Mortal Kombat 4 WWE All Stars 5 INITIAL

GAMELIST / LISTADO DE JUEGOS 1 Tekken 6 2 Tekken 5 3 Mortal Kombat 4 WWE All Stars 5 INITIAL D 6 Guilty Gear XX Accent Core Plus 7 Soulcalibur Broken Destiny 8 Dragon Ball Z 9 Mega Man X Maverick Hunter 10 LocoRoco 11 Turtledove (Chinese version) 12 Cartoon hero VS Capcom 2 (American version) 13 Death or Life 2 (American Version) 14 VR Soldier Group 3 (European version) 15 Street Fighter Alpha 3 16 Street Fighter EX 17 Bloody Roar 2 18 Tekken 3 19 Tekken 2 20 Tekken 21 Golden Eye 007 22 1080 Snowboarding 23 Aero Gauge 24 Air Boarder 64 25 Akumajou Dracula Mokushiroku - Real Action Adventure 26 All Star Tennis '99 27 Army Men - Sarge's Heroes 28 Automobili Lamborghini 29 Batman Beyond - Return of the Joker 30 Beetle Adventure Racing! 31 Big Mountain 2000 32 Bio F.R.E.A.K.S. 33 Blues Brothers 2000 34 Bomberman Hero 35 Buck Bumble 36 A Bug's Life 37 Bust A Move '99 38 Carmageddon 64 39 Centre Court Tennis 40 Chameleon Twist 41 Chameleon Twist 2 42 Choro Q 64 43 City Tour Grandprix - Zennihon GT Senshuken 44 Clay Fighter - Sculptor's Cut 45 Cruis'n World 46 Cyber Tiger 47 Destruction Derby 64 48 Dezaemon 3D 49 Doraemon 2 - Nobita to Hikari no Shinden 50 Dual Heroes 51 Extreme-G 52 Extreme-G XG2 53 F-ZERO X 54 Flying Dragon 55 Ganbare Goemon - Derodero Douchuu Obake Tenkomori 56 Gex 3 - Deep Cover Gecko 57 HSV Adventure Racing 58 Hybrid Heaven 59 Bass Hunter 64 60 Indy Racing 2000 61 Jeremy McGrath Super 62 Jikkyou Powerful Pro Yakyuu 2000 63 Killer Instinct Gold 64 Mace - The Dark Age 65 Mario Kart 64 66 Mickey no Racing Challenge USA 67 Mission Impossible 68 Monaco Grand Prix 69 Mortal Kombat 4 70 Ms. -

Games 22 Hitman Reborn 638 B.Rap Boys 1254 Traverse USA 1870 Puggsy 23 Magical Girl 639 Bad Dudes Vs

No. English No. English No. English No. English 1 Tekken 6 617 Akuma-Jou Dracula 1233 Thunder & Lightning 1849 Pack'n Bang Bang 2 Tekken 5 618 Alex Kidd 1234 Thunder Fox 1850 Packetman 3 Mortal Kombat 619 Alien Sector 1235 Thunder Fox USA 1851 Pacu-Man 4 Soul Eater 620 Alien Storm 1 1236 Thunder Heroes 1852 Pass 5 Weekly 621 Alien Storm 2 1237 Thunder Zone 1853 Pipi & Bibis 6 WWE All Stars 622 Alien Syndrome 1238 ThunderJaws 1854 Piranha 7 Monster Hunter 3 623 Alien VS Predator 1239 Tickee Tickats 1855 Elemental Master 8 Final Fantasy:Type-0 624 Aliens 1240 Tiger Road 1856 Exile 9 Kidou Senshi Gundam 625 Alligator Hunt 1241 Time Fighter 1857 F1 10 Naruto Shippuuden Naltimate Impact 626 Altered Beast 1 1242 Time Limit 1858 FIFA International Soccer 11 Daxter 627 Aquajack 1243 Time's Up Demo 1859 Fun Car Rally 12 Assassin's Creed - Bloodlines 628 Arabian 1244 Tinkle Pit 1860 Garfield 13 Kingdom Hearts - Birth by Sleep 629 Argus no Senshi 1245 Tip Top 1861 The Incredible Hulk 14 BLAZBLUE 630 Armored Car 1246 Toki 1862 Chaotic instruments 15 Pro Evolution Soccer 2012 631 Armored Warriors 1247 Toki US Prototype 1863 Iraq War 2003 16 Basketball NBA 06 632 Asterix 1248 Top Roller 1864 Judge Dredd 17 Ridge Racer 2 633 Atomic Punk 1249 Top Secret 1865 Jurassic Park - Rampage Edition 18 HeatSeeker 634 Atomic Robo-kid 1250 Top Speed 1866 Jurassic Park 19 INITIAL D 635 Aurail 2 1251 Toppy & Rappy 1867 Junker's High 20 Gran Turismo 636 Avengers 1252 Toride 2 1868 Tougiou King Colossus 21 WipeOut 637 B.C. -

Ultimate Multigame Full Games List: 10-YARD FIGHT – (1/2P) – (1464

Ultimate Multigame Full Games List: 10-YARD FIGHT – (1/2P) – (1464) 16 ZHANG MA JIANG – (1/2P) – (2391) 1941 : COUNTER ATTACK – (1/2P) – (860) 1942 – (1/2P) – (861) 1942 – AIR BATTLE – (1/2P) – (1140) 1943 : THE BATTLE OF MIDWAY – (1/2P) – (862) 1943 KAI : MIDWAY KAISEN – (1/2P) – (863) 1943: THE BATTLE OF MIDWAY – (1/2P) – (1141) 1944 : THE LOOP MASTER – (1/2P) – (780) 1945KIII – (1/2P) – (856) 19XX : THE WAR AGAINST DESTINY – (1/2P) – (864) 2 ON 2 OPEN ICE CHALLENGE – (1/2P) – (1415) 2020 SUPER BASEBALL – (1/2P) – (1215) 3 COUNT BOUT – (1/2P) – (1312) 4 EN RAYA – (1/2P) – (1612) 4 FUN IN 1 – (1/2P) – (965) 46 OKUNEN MONOGATARI – (1/2P) – (2711) 4-D WARRIORS – (1/2P) – (830) 64TH. STREET : A DETECTIVE STORY – (1/2P) – (402) 6-PAK – (1/2P) – (2196) 7 ORDI – (1/2P) – (1798) 720 DEGREES REV 4 – (1/2P) – (1369) 777 FIGHTER – (1/2P) – (2807) 88GAMES – (1/2P) – (1258) 88GAMES – (4P) – (2989) 9 BALL SHOOTOUT – (1/2P) – (1227) 99 : THE LAST WAR – (1/2P) – (1035) A DINOSAUR’S TALE – (1/2P) – (2188) D. 2083 – (1/2P) – (998) AAAHH! REAL MONSTERS – (1/2P) – (2547) AAAHH! REAL MONSTERS-U BLOOD – (1/2P) – (2546) AAAHH!!! REAL MONSTERS – (1/2P) – (2232) ACCELEBRID – (1/2P) – (2632) ACROBAT MISSION – (1/2P) – (931) ACROBAT MISSION – (1/2P) – (2680) ACROBATIC DOG-FIGHT – (1/2P) – (980) ACT-FANCER CYBERNETICK HYPER – (1/2P) – (419) ACTION 52 – (1/2P) – (2414) ACTION FIGHTER – (1/2P) – (1093) ACTION HOLLYWOOOD – (1/2P) – (362) ADDAMS FAMILY VALUES – (1/2P) – (2431) ADVENTUROUS BOY-MAO XIAN XIAO ZI – (1/2P) – (2266) AERO FIGHTERS – (1/2P) – (927) AERO FIGHTERS -

The Place of Classical Chinese Literature in Modern Sino- Japanese Pop Culture: the Case of Cao Cao in Sanguo Yanyi

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM Honors College Senior Theses Undergraduate Theses 2015 The Place of Classical Chinese Literature in Modern Sino- Japanese Pop Culture: The Case of Cao Cao in Sanguo Yanyi Jonathan M. Heinrichs The University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses Recommended Citation Heinrichs, Jonathan M., "The Place of Classical Chinese Literature in Modern Sino-Japanese Pop Culture: The Case of Cao Cao in Sanguo Yanyi" (2015). UVM Honors College Senior Theses. 217. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/217 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM Honors College Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 The Place of Classical Chinese Literature in Modern SinoJapanese Pop Culture: The Case of Cao Cao in Sanguo Yanyi A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for College Honors Jonathan M. Heinrichs College of Arts and Sciences The University of Vermont Spring 2015 2 Table of Contents Introduction.......................................................................................................................3 Cao Cao in Sanguo Yanyi An Overview............................................................................7 The Ambition of Cao Cao in Chinese Adaptations............................................................10