Migration in Nepal: a Country Profile 2019 Iii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Civil Society in Uncivil Places: Soft State and Regime Change in Nepal

48 About this Issue Recent Series Publications: Policy Studies 48 Policy Studies Policy This monograph analyzes the role of civil Policy Studies 47 society in the massive political mobilization Supporting Peace in Aceh: Development and upheavals of 2006 in Nepal that swept Agencies and International Involvement away King Gyanendra’s direct rule and dra- Patrick Barron, World Bank Indonesia matically altered the structure and character Adam Burke, London University of the Nepali state and politics. Although the opposition had become successful due to a Policy Studies 46 strategic alliance between the seven parlia- Peace Accords in Northeast India: mentary parties and the Maoist rebels, civil Journey over Milestones Places in Uncivil Society Civil society was catapulted into prominence dur- Swarna Rajagopalan, Political Analyst, ing the historic protests as a result of nation- Chennai, India al and international activities in opposition to the king’s government. This process offers Policy Studies 45 new insights into the role of civil society in The Karen Revolution in Burma: Civil Society in the developing world. Diverse Voices, Uncertain Ends By focusing on the momentous events of Ardeth Maung Thawnghmung, University of the nineteen-day general strike from April Massachusetts, Lowell 6–24, 2006, that brought down the 400- Uncivil Places: year-old Nepali royal dynasty, the study high- Policy Studies 44 lights the implications of civil society action Economy of the Conflict Region within the larger political arena involving con- in Sri Lanka: From Embargo to Repression ventional actors such as political parties, trade Soft State and Regime Muttukrishna Sarvananthan, Point Pedro unions, armed rebels, and foreign actors. -

Nepal Human Rights Year Book 2021 (ENGLISH EDITION) (This Report Covers the Period - January to December 2020)

Nepal Human Rights Year Book 2021 (ENGLISH EDITION) (This Report Covers the Period - January to December 2020) Editor-In-Chief Shree Ram Bajagain Editor Aarya Adhikari Editorial Team Govinda Prasad Tripathee Ramesh Prasad Timalsina Data Analyst Anuj KC Cover/Graphic Designer Gita Mali For Human Rights and Social Justice Informal Sector Service Centre (INSEC) Nagarjun Municipality-10, Syuchatar, Kathmandu POBox : 2726, Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: +977-1-5218770 Fax:+977-1-5218251 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.insec.org.np; www.inseconline.org All materials published in this book may be used with due acknowledgement. First Edition 1000 Copies February 19, 2021 © Informal Sector Service Centre (INSEC) ISBN: 978-9937-9239-5-8 Printed at Dream Graphic Press Kathmandu Contents Acknowledgement Acronyms and Abbreviations Foreword CHAPTERS Chapter 1 Situation of Human Rights in 2020: Overall Assessment Accountability Towards Commitment 1 Review of the Social and Political Issues Raised in the Last 29 Years of Nepal Human Rights Year Book 25 Chapter 2 State and Human Rights Chapter 2.1 Judiciary 37 Chapter 2.2 Executive 47 Chapter 2.3 Legislature 57 Chapter 3 Study Report 3.1 Status of Implementation of the Labor Act at Tea Gardens of Province 1 69 3.2 Witchcraft, an Evil Practice: Continuation of Violence against Women 73 3.3 Natural Disasters in Sindhupalchok and Their Effects on Economic and Social Rights 78 3.4 Problems and Challenges of Sugarcane Farmers 82 3.5 Child Marriage and Violations of Child Rights in Karnali Province 88 36 Socio-economic -

![Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area Cggk"0F{ ;+/If0f If]Qsf :Tgwf/L Jgohgt' Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area - 2019](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7316/wild-mammals-of-the-annapurna-conservation-area-cggk-0f-if0f-if-qsf-tgwf-l-jgohgt-wild-mammals-of-the-annapurna-conservation-area-2019-127316.webp)

Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area Cggk"0F{ ;+/If0f If]Qsf :Tgwf/L Jgohgt' Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area - 2019

Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area cGgk"0f{ ;+/If0f If]qsf :tgwf/L jGohGt' Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area - 2019 ISBN 978-9937-8522-8-9978-9937-8522-8-9 9 789937 852289 National Trust for Nature Conservation Annapurna Conservation Area Project Khumaltar, Lalitpur, Nepal Hariyo Kharka, Pokhara, Kaski, Nepal National Trust for Nature Conservation P.O. Box: 3712, Kathmandu, Nepal P.O. Box: 183, Kaski, Nepal Tel: +977-1-5526571, 5526573, Fax: +977-1-5526570 Tel: +977-61-431102, 430802, Fax: +977-61-431203 Annapurna Conservation Area Project Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Website: www.ntnc.org.np Website: www.ntnc.org.np 2019 Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area cGgk"0f{ ;+/If0f If]qsf :tgwf/L jGohGt' National Trust for Nature Conservation Annapurna Conservation Area Project 2019 Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area cGgk"0f{ ;+/If0f If]qsf :tgwf/L jGohGt' Published by © NTNC-ACAP, 2019 All rights reserved Any reproduction in full or in part must mention the title and credit NTNC-ACAP. Reviewers Prof. Karan Bahadur Shah (Himalayan Nature), Dr. Naresh Subedi (NTNC, Khumaltar), Dr. Will Duckworth (IUCN) and Yadav Ghimirey (Friends of Nature, Nepal). Compilers Rishi Baral, Ashok Subedi and Shailendra Kumar Yadav Suggested Citation Baral R., Subedi A. & Yadav S.K. (Compilers), 2019. Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area. National Trust for Nature Conservation, Annapurna Conservation Area Project, Pokhara, Nepal. First Edition : 700 Copies ISBN : 978-9937-8522-8-9 Front Cover : Yellow-bellied Weasel (Mustela kathiah), back cover: Orange- bellied Himalayan Squirrel (Dremomys lokriah). -

The Madhesi Movement in Nepal: a Study on Social, Cultural and Political Aspects, 1990- 2015

THE MADHESI MOVEMENT IN NEPAL: A STUDY ON SOCIAL, CULTURAL AND POLITICAL ASPECTS, 1990- 2015 A Dissertation Submitted To Sikkim University In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirement for the Degree of Master of Philosophy By Anne Mary Gurung DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES February, 2017 DECLARATION I, Anne Mary Gurung, do hereby declare that the subject matter of this dissertation is the record of the work done by me, that the contents of this dissertation did not form the basis of the award of any previous degree to me or to the best of my knowledge to anybody else, and that the dissertation has not been submitted by me for any research degree in any other university/ institute. The dissertation has been checked by using URKUND and has been found within limits as per plagiarism policy and instructions issued from time to time. This dissertation is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science, School of Social Sciences, Sikkim University. Name: Anne Mary Gurung Registration Number: 15/M.Phil/PSC/01 We recommend that this dissertation be placed before the examiners for evaluation. Durga Prasad Chhetri Swastika Pradhan Head of the Department Supervisor CERTIFICATE This to certify that the dissertation entitled, “The Madhesi Movement in Nepal: A Study on Social, Cultural and Political Aspects, 1990-2015” submitted to Sikkim University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy in Political Science is the result of bonafide research work carried out by Ms. -

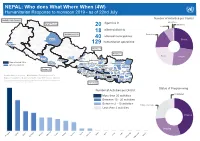

NEPAL: Who Does What Where When (4W)

NEPAL: Who does What Where When (4W) Humanitarian Response to monsoon 2019 - as of 22nd July Number of Activities per Cluster SudurPaschim Province Agencies in Education Karnali Province Nutrition 20 Health Darchula 18 affected districts Gandaki Province Protection affected municipalities Province 7 Province 6 Dolpa 40 Shelter humanitarian operations Kanchanpur 129 Kanchanpur Kailali Province 4 Province 3 Bardiya Gorkha Kaski Province 1 Rasuwa Food Banke Province 5 WASH Dang Tanahu Dhading Dang ProvinceKathmandu 3 Palpa KathmanduDhading Dolakha Most affected HHs Kathmandu KapilbastuKapilbastu Nawalparasi Kavrepalanchok Sankhuwasabha Rupandehi Chitawan Affected Districts MakwanpurMakwanpurLalitpurLalitpur Ramechhap ProvinceTaplejung 1 Okhaldhunga Province 5 Parsa SindhuliSindhuli Parsa Khotang Bhojpur Bara PanchtharPanchthar Sarlahi Rautahat Sarlahi Udayapur DhankutaBara Rautahat MahottariDhanusa Udayapur Ilam Creation date: 23 July 2019 Glide Number: FL-2019-000083-NPL Mahottari DhanusaSiraha Sunsari Sources: Nepal Survey Department, MoHA, Nepal HCT clusters - 22nd July Siraha SaptariSunsari Morang Jhapa The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply ocial Province 2 Saptari Morang Jhapa endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Province 2 Status of Programming Number of Activities per District Completed More than 20 activities Between 10 - 20 activities Between 2 - 10 activities Status unknown Less than 2 activities Planned On-going Bara Parsa Banke Kaski Kaski Sarlahi Siraha Morang Udayapur Saptari Sunsari Sindhuli Surkhet Rautahat Mahottari Dhanusa Kathmandu Makwanpur Early Grand District Education Health Nutrition WASH Shelter/NFI Logistic Food Protection Recovery Total Banke 1 1 Bara 1 1 Dhanusa 2 2 Kailai 1 1 Kaski 1 1 Kathmandu 1 1 Mahottari 1 2 2 7 12 Makwanpur 1 1 Morang 2 6 1 9 Parsa 1 1 2 Rautahat 1 8 5 6 8 28 Saptari 2 2 2 2 8 Sarlahi 1 4 2 9 4 20 Sindhuli 1 5 6 Siraha 1 4 1 5 2 13 Sunsari 1 1 5 7 Surkhet 0 1 0 0 1 Udayapur 1 1 5 2 9 N/A 1 3 1 1 6 Grand Total 1 10 1 31 36 0 29 21 0 129. -

Oli's Temple Visit Carries an Underlying Political Message, Leaders and Observers

WITHOUT F EAR OR FAVOUR Nepal’s largest selling English daily Vol XXVIII No. 329 | 8 pages | Rs.5 O O Printed simultaneously in Kathmandu, Biratnagar, Bharatpur and Nepalgunj 24.5 C -5.4 C Tuesday, January 26, 2021 | 13-10-2077 Dipayal Jumla Campaigners decry use of force by police on peaceful civic protest against the House dissolution move Unwarned, protesters were hit by water cannons and beaten up as they marched towards Baluwatar. Earlier in the day, rights activists were rounded up from same area. ANUP OJHA Dahayang Rai, among others, led the KATHMANDU, JAN 25 protest. But no sooner had the demonstra- The KP Sharma Oli administration’s tors reached close to Baluwatar, the intolerance of dissent and civil liberty official residence of Prime Minister was in full display on Monday. Police Oli, than police charged batons and on Monday afternoon brutally charged used water cannons to disperse them, members of civil society, who had in what was reminiscent of the days gathered under the umbrella of Brihat when protesters were assaulted dur- Nagarik Andolan, when they were ing the 2006 movement, which is marching towards Baluwatar to pro- dubbed the second Jana Andolan, the test against Oli’s decision to dissolve first being the 1990 movement. the House on December 20. The 1990 movement ushered in In a statement in the evening, democracy in the country and the sec- Brihat Nagarik Andolan said that the ond culminated in the abolition of government forcefully led the peaceful monarc h y. protest into a violent clash. In a video clip by photojournalist “The police intervention in a Narayan Maharjan of Setopati, an peaceful protest shows KP Sharma online news portal, Wagle is seen fall- Oli government’s fearful and ing down due to the force of the water suppressive mindset,” reads the cannon, and many others being bru- POST PHOTO: ANGAD DHAKAL statement. -

A Connectivity-Driven Development Strategy for Nepal: from a Landlocked to a Land-Linked State

ADBI Working Paper Series A Connectivity-Driven Development Strategy for Nepal: From a Landlocked to a Land-Linked State Pradumna B. Rana and Binod Karmacharya No. 498 September 2014 Asian Development Bank Institute Pradumna B. Rana is an associate professor at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Binod Karmacharya is an advisor at the South Asia Centre for Policy Studies (SACEPS), Kathmandu, Nepal Prepared for the ADB–ADBI study on “Connecting South Asia and East Asia.” The authors are grateful for the comments received at the Technical Workshop held on 6–7 November 2013. The views expressed in this paper are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of ADBI, ADB, its Board of Directors, or the governments they represent. ADBI does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this paper and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. Terminology used may not necessarily be consistent with ADB official terms. Working papers are subject to formal revision and correction before they are finalized and considered published. “$” refers to US dollars, unless otherwise stated. The Working Paper series is a continuation of the formerly named Discussion Paper series; the numbering of the papers continued without interruption or change. ADBI’s working papers reflect initial ideas on a topic and are posted online for discussion. ADBI encourages readers to post their comments on the main page for each working paper (given in the citation below). Some working papers may develop into other forms of publication. Suggested citation: Rana, P., and B. -

Assessment of Antenatal Care Services Among Pregnant Women in Omani Polyclinics

ISSN: 2638-1605 Madridge Journal of Nursing Research Article Open Access Assessment of Antenatal Care services among Pregnant Women in Omani Polyclinics Al-Abri HA, Al-Balushi IM, AL-Malki SR, Al-Jahwari KA, AL-Sabqi AH, AL-Mushaifary NA, and Hameed Swadi Hassan* School of Pharmacy, College of Pharmacy and Nursing, University of Nizwa, Oman Article Info Abstract *Corresponding author: Background: Since the antenatal care is important screening for the health of the Hameed Swadi Hassan pregnant woman and the child to achieve the best possible outcome, it is chosen to Associate Professor School of Pharmacy assess this screening in 6 government polyclinics in different regions in Oman during College of Pharmacy and Nursing January 2011. University of Nizwa Birkat Al-Mouz Method: This retrospective study was carried out in six different regions in Oman by Nizwa, Oman using the available data of 6 polyclinics. The results are reported according to a prepared E-mail: [email protected] data collection forms for 1200 Omani pregnant women during January 2011. Data collection forms were designed and included demographic parameters and other Received: April 2, 2019 Accepted: April 25, 2019 parameters chosen from similar previous studies. All the obtained results are presented Published: May 3, 2019 in tables region wise. Results: The age of the investigated pregnant women in this study was found to range Citation: Al-Abri HA, Al-Balushi IM, AL-Malki SR, et al. Assessment of Antenatal Care services from 18-49 years with a majority (65.8%) of 20-35 years and about 80% of them were among Pregnant Women in Omani Polyclinics. -

UNODC Multi-Country Study on Trafficking in Persons and Smuggling of Migrants from Nepal

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Regional Office for SouthAsia September 2019 Copyright © UNODC 2019 Disclaimer: The designations employed and the contents of this publication, do not imply the expression or endorsement of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNODC concerning the legal status of any country, territory or city, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. EP 16/17, Chandragupta Marg, Chanakyapuri New Delhi - 110021, India Tel: +91 11 24104964/66/68 Website: www.unodc. org/southasia/ Follow UNODC South Asia on: This is an internal UNODC document, which is not meant for wider public distribution and is a component of ongoing, expert research undertaken by the UNODC under the GLO.ACT project. The objective of this study is to identify pressing needs and offer strategic solutions to support the Government of Nepal and its law enforcement agencies in areas covered by UNODC mandates, particularly the smuggling of migrants. This report has not been formally edited, and its contents do not necessarily reflect or imply endorsement of the views or policies of the UNODC or any contributory organizations. In addition, the designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply any particular opinion whatsoever regarding the legal status of any country, territory, municipality or its authorities, or the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The boundaries and names shown, and the designations used in all the maps in this report, do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations and the UNODC. TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 3 ABBREVIATIONS 4 KEY TERMS USED IN THE REPORT AND THEIR DEFINITIONS/MEANINGS 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 7 1. -

JWAC Lesson Plan Bhutan: a Case Study on Ethnic Cleansing By: Emma Sheean, November 2017

JWAC Lesson Plan Bhutan: A Case Study on Ethnic Cleansing By: Emma Sheean, November 2017 Warm up: Are you familiar with Bhutan? If so, what do you know about it? Fast Facts: The capital, Thimpu, is home to 104,000 people and is the only capital in the world (besides Pyongyang) without traffic lights Measures prosperity by Gross National Happiness, not Gross Domestic Product Main language: Dzongkha/Bhutanese is official, but used by only 24% of the population—others are Sharchhopka and Lhotshamkha Discussion: A landlocked country in the Himalayas, Bhutan is not as well-known as its mountainous neighbor, Nepal. With a total population under a million (estimated to be 758,288) Bhutan slips under the radar. Yet the country has impressive environmental initiatives and has even banned the sale of tobacco as a measure to promote the health of its citizens. Bhutan has many positive features deriving from its efforts to maintain Gross National Happiness; however, its history is haunted by events that took place in the 1990s: a forced exodus of the country’s Nepalese minority. Case Study: The Lhotshampa Refugees Background: A wave of illegal immigration of ethnic Nepalese in from 1950-1980 led to a very large Lhotshampa population, discovered by Bhutan in their first census in 1988. Alarmed by the size of the Nepalese minority, Bhutan implemented several measures to assimilate the population, including mandating Bhutanese cultural dress and forbidding the teaching of the Nepali language in schools. Those who protested these policies were imprisoned, subject to torture and denied a fair trial. Several protests turned violent and led to conflict between the Nepalese minority and the Bhutanese government security forces. -

Molecular Genetic Studies of Inherited Cystic Kidney Disease in Oman

Molecular Genetic Studies of Inherited Cystic Kidney Disease in Oman Intisar Hamed Al Alawi A Thesis Submitted For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institute of Genetic Medicine Newcastle University January 2020 Abstract Inherited kidney diseases are fundamental causes of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end stage kidney disease (ESKD); accounting for approximately 20% of all CKD cases and up to 10% of adults and over 70% of children reaching ESKD. Oman is the second largest country in the South East of Arabian Peninsula. Omani population is characterized by large family size, presence of tribal and geographical settlements and higher rates of consanguineous marriages, which facilitate the study of autosomal recessive disorders. Rare genetic disorders create considerable burden on healthcare system in Oman and are major causes of congenital abnormalities and perinatal deaths in hospitals. The prevalence of inherited kidney disease was estimated to be high, but there is a lack for a comprehensive data. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the magnitude of inherited kidney disease in this population and identify the molecular genetic causes of inherited cystic kidney diseases in Omani patients. First, I performed a population-based retrospective analysis of ESKD patients commencing RRT from 2001 to 2015 using the national renal replacement therapy (RRT) registry and evaluated the epidemiological and etiological causes of ESKD with focused attention on inherited kidney diseases. Second, I designed a targeted gene panel (49 genes) and used massive parallel sequencing technologies for the molecular genetic diagnosis of cystic kidney disease in 53 patients. An overall molecular genetic diagnostic yield of 75% was achieved; with 46% of detected causative variants were novel genetic findings. -

Considering Dalits and Political Identity In

#$%&'#(')$#*%+,'-.+%/0$'$1.$,1/)'2,/3*%4/1& )+,4/0*%/,5'0$./14'$,0' 6+./1/)$.'/0*,1/1&'/,'/#$5/,/,5' $',*7',*6$. In this article I examine the articulation between contexts of agency within two kinds of discur- sive projects involving Dalit identity and caste relations in Nepal, so as to illuminate competing and complimentary forms of self and group identity that emerge from demarcating social perim- eters with political and economic consequences. The first involves a provocative border created around groups of people called Dalit by activists negotiating the symbols of identity politics in the country’s post-revolution democracy. Here subjective agency is expressed as political identity with attendant desires for social equality and power-sharing. The second context of Dalit agency emerges between people and groups as they engage in inter caste economic exchanges called riti maagnay in mixed caste communities that subsist on interdependent farming and artisan activi- ties. Here caste distinctions are evoked through performed communicative agency that both resists domination and affirms status difference. Through this examination we find the rural terrain that is home to landless and poor rural Dalits only partially mirrors that evoked by Dalit activists as they struggle to craft modern identities. The sources of data analyzed include ethnographic field research conducted during various periods from 1988-2005, and discussions that transpired through- out 2007 among Dalit activist members of an internet discussion group called nepaldalitinfo.