Alaris Capture Pro Software

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE ROSES ✥ 9 10 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 20 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 30 1 2 3 4 5 36 37 38X

This content downloaded from 136.167.3.36 on Thu, 11 Jan 2018 18:42:15 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 ✥ THE WARS OF THE ROSES ✥ 9 10 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 20 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 30 1 2 3 4 5 36 37 38x This content downloaded from 136.167.3.36 on Thu, 11 Jan 2018 18:42:15 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 THE WARS OF 8 9 ✥ ✥ 10 THE ROSES 1 2 3 MICHAEL HICKS 4 5 6 7 8 9 20 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 30 1 2 3 4 5 36 YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS 37 NEW HAVEN AND LONDON 38x This content downloaded from 136.167.3.36 on Thu, 11 Jan 2018 18:42:15 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Copyright © 2010 Michael Hicks 8 9 All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and 20 except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publishers. 1 For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, please contact: 2 U.S. Office: [email protected] www.yalebooks.com 3 Europe Office: sales @yaleup.co.uk www.yaleup.co.uk 4 Set in Minion Pro by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd 5 Printed in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall 6 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data 7 8 Hicks, M. -

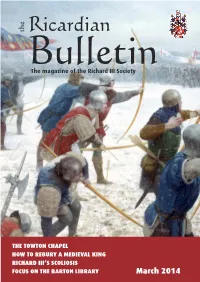

Ricardian Bulletin March 2014 Text Layout 1

the Ricardian Bulletin The magazine of the Richard III Society THE TOWTON CHAPEL HOW TO REBURY A MEDIEVAL KING RICHARD III’S SCOLIOSIS FOCUS ON THE BARTON LIBRARY March 2014 Advertisement the Ricardian Bulletin The magazine of the Richard III Society March 2014 Richard III Society Founded 1924 Contents www.richardiii.net 2 From the Chairman In the belief that many features of the tradi- 3 Reinterment news Annette Carson tional accounts of the character and career of 4 Members’ letters Richard III are neither supported by sufficient evidence nor reasonably tenable, the Society 7 Society news and notices aims to promote in every possible way 12 Future Society events research into the life and times of Richard III, 14 Society reviews and to secure a reassessment of the material relating to this period and of the role in 16 Other news, reviews and events English history of this monarch. 18 Research news Patron 19 Richard III and the men who died in battle Lesley Boatwright, HRH The Duke of Gloucester KG, GCVO Moira Habberjam and Peter Hammond President 22 Looking for Richard – the follow-up Peter Hammond FSA 25 How to rebury a medieval king Alexandra Buckle Vice Presidents 37 The Man Himself: The scoliosis of Richard III Peter Stride, Haseeb John Audsley, Kitty Bristow, Moira Habberjam, Qureshi, Amin Masoumiganjgah and Clare Alexander Carolyn Hammond, Jonathan Hayes, Rob 39 Articles Smith. 39 The Third Plantagenet John Ashdown-Hill Executive Committee 40 William Hobbys Toni Mount Phil Stone (Chairman), Paul Foss, Melanie Hoskin, Gretel Jones, Marian Mitchell, Wendy 42 Not Richard de la Pole Frederick Hepburn Moorhen, Lynda Pidgeon, John Saunders, 44 Pudding Lane Productions Heather Falvey Anne Sutton, Richard Van Allen, 46 Some literary and historical approaches to Richard III with David Wells, Susan Wells, Geoffrey Wheeler, Stephen York references to Hungary Eva Burian 47 A series of remarkable ladies: 7. -

5 Tudor Textbook for GCSE to a Level Transition

Introduction to this book The political context in 1485 England had experienced much political instability in the fifteenth century. The successful short reign of Henry V (1413-22) was followed by the disastrous rule of Henry VI. The shortcomings of his rule culminated in the s outbreak of the so-called Wars of the Roses in 1455 between the royal houses of Lancaster and York. England was then subjected to intermittent civil war for over thirty years and five violent changes of monarch. Table 1 Changes of monarch, 1422-85 Monarch* Reign The ending of the reign •S®^^^^^3^^!6y^':: -; Defeated in battle and overthrown by Edward, Earl of Henry VI(L] 1422-61 March who took the throne. s Overthrown by Warwick 'the Kingmaker' and forced 1461-70 Edward IV [Y] into exile. Murdered after the defeat of his forces in the Battle of Henry VI [L] 1470-?! Tewkesbury. His son and heir, Edward Prince of Wales, was also killed. Died suddenly and unexpectedly, leaving as his heir 1471-83 Edward IV [Y] the 13-year-old Edward V. Disappeared in the Tower of London and probably murdered, along with his brother Richard, on the orders of Edward V(Y] 1483 his uncle and protector, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, who succeeded him on the throne. Defeated and killed at the Battle of Bosworth. Richard III [Y] 1483-85 Succeeded on the throne by his successful adversary Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond. •t *(L]= Lancaster [Y)= York / Sence Brook RICHARD King Dick's Hole ao^_ 00/ g •%°^ '"^. 6'^ Atterton '°»•„>••0' 4<^ Bloody. -

Renaissance Texts, Medieval Subjectivities: Vernacular Genealogies of English Petrarchism from Wyatt to Wroth

Renaissance Texts, Medieval Subjectivities: Vernacular Genealogies of English Petrarchism from Wyatt to Wroth by Danila A. Sokolov A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Waterloo, Ontario, Canada 2012 © Danila A. Sokolov 2012 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This dissertation investigates the symbolic presence of medieval forms of textual selfhood in early modern English Petrarchan poetry. Seeking to problematize the notion of Petrarchism as a Ren- aissance discourse par excellence, as a radical departure from the medieval past marking the birth of the modern poetic voice, the thesis undertakes a systematic re-reading of a significant body of early modern English Petrarchan texts through the prism of late medieval English poetry. I argue that me- dieval poetic texts inscribe in the vernacular literary imaginary (i.e. a repository of discursive forms and identities available to early modern writers through antecedent and contemporaneous literary ut- terances) a network of recognizable and iterable discursive structures and associated subject posi- tions; and that various linguistic and ideological traces of these medieval discourses and selves can be discovered in early modern English Petrarchism. Methodologically, the dissertation’s engagement with poetic texts across the lines of periodization is at once genealogical and hermeneutic. The prin- cipal objective of the dissertation is to uncover a vernacular history behind the subjects of early mod- ern English Petrarchan poems and sonnet sequences. -

Route a Pre-Work Booklet Henry VII, 1485-1509

- AQA Paper 1C: The Tudors, 1485-1603 Henry VII, 1485-1509 booklet 1 Overview of Henry VII’s reign This booklet contains the essential information that you will need to have for this first part of the Tudors topic. The first area is concerned with the first Tudor monarch, Henry Tudor. He came to the throne after defeating the then unpopular Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485. After taking power Henry VII then needed to exert his power over England. This then involves understanding the following: 1. how he was able to defeat his enemies; 2. how England was governed during his reign; 3. what was his relations with other countries through his foreign policy; 4. the state of religion during his reign; 5. the changes to the economy during his reign, and 6. the changes to society during his reign How this booklet works The booklet is divided into the six topic areas as listed above. For each section there is an essential reading of the topic area containing the important information. Always refer to this section when you are confused or need clarification. This is to support your textbook which will give you the information in greater detail. There will be one or two key questions relating to the information that form the focus for the week’s work in class and home. Make sure that you complete the pre-work so that you can come to the lessons prepared to progress more analytical thinking of these issues. There are some initial tasks that involve knowledge acquisition followed by more analytical questioning, culminating with an exam focus. -

The University of Hull the Early Career of Thomas

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL THE EARLY CAREER OF THOMAS, LORD HOWARD, EARL OF SURREY AND THIRD DUKE OF NORFOLK, 1474—c. 1525 being a Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Hull by Susan Elisabeth Vokes, B.A. September, 1988 Acknowledgements I should like to thank the University of Hull for my postgraduate scholarship, and the Institute of Historical Research and Eliot College, the Universiy of Kent, for providing excellent facilities in recent years. I am especially grateful to the Duke of Norfolk and his archivists for giving me access to material in his possession. The staff of many other archives and libraries have been extremely helpful in answering detailed enquiries and helping me to locate documents, and / regret that it is not possible to acknowledge them individually. I am grateful to my supervisor, Peter Heath, for his patience, understanding and willingness to read endless drafts over the years in which this study has evolved. Others, too, have contributed much. Members of the Russell/Starkey seminar group at the Institute of Historical Research, and the Late Medieval seminar group at the University of Kent made helpful comments on a paper, and I have benefitted from suggestions, discussion, references and encouragement from many others, particularly: Neil Samman, Maria Dowling, Peter Gwynn, George Bernard, Greg Walker and Diarmaid MacCulloch. I am particularly grateful to several people who took the trouble to read and comment on drafts of various chapters. Margaret Condon and Anne Crawford commented on a draft of the first chapter, Carole Rawcliffe and Linda Clerk on my analysis of Norfolk's estate accounts, Steven Ellis on my chapters on Surrey in Ireland and in the north of England, and Roger Virgoe on much of the thesis, including all the East Anglian material. -

Usurpation, Propaganda and State-Influenced History in Fifteenth-Century England

"Winning the People's Voice": Usurpation, Propaganda and State-influenced History in Fifteenth-Century England. By Andrew Broertjes, B.A (Hons) This thesis is presented for the Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Western Australia Humanities History 2006 Table of Contents Abstract Acknowledgements Introduction p. 1 Chapter One: Political Preconditions: Pretenders, Usurpation and International Relations 1398-1509. p. 19 Chapter Two: "The People", Parliament and Public Revolt: the Construction of the Domestic Audience. p. 63 Chapter Three: Kingship, Good Government and Nationalism: Contemporary Attitudes and Beliefs. p. 88 Chapter Four: Justifying Usurpation: Propaganda and Claiming the Throne. p. 117 Chapter Five: Promoting Kingship: State Propaganda and Royal Policy. p. 146 Chapter Six: A Public Relations War? Propaganda and Counter-Propaganda 1400-1509 p. 188 Chapter Seven: Propagandistic Messages: Themes and Critiques. p. 222 Chapter Eight: Rewriting the Fifteenth Century: English Kings and State Influenced History. p. 244 Conclusion p. 298 Bibliography p. 303 Acknowledgements The task of writing a doctoral thesis can be at times overwhelming. The present work would not be possible without the support and assistance of the following people. Firstly, to my primary supervisor, Professor Philippa Maddern, whose erudite commentary, willingness to listen and general support since my undergraduate days has been both welcome and beneficial to my intellectual growth. Also to my secondary supervisor, Associate Professor Ernie Jones, whose willingness to read and comment on vast quantities of work in such a short space of time has been an amazing assistance to the writing of this thesis. Thanks are also owed to my reading group, and their incisive commentary on various chapters. -

The Genealogy of Ervin Billy Lawson

The Genealogy of Ervin Billy Lawson The Genealogy of Ervin Billy Lawson © 2013 by John Robert Cole All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system now known or hereafter invented, without written permission from the author. ERVIN BILLY LAWSON Born 16 Sep 1952, Spartanburg, South Carolina TABLE OF CONTENTS LAWSON ............................................................................................................................... 1 GARNER............................................................................................................................. 29 LAWSON ............................................................................................................................ 41 OWENS .............................................................................................................................. 45 CLAYTON .......................................................................................................................... 57 LEOPARD .......................................................................................................................... 65 ETHEREDGE ..................................................................................................................... 73 HART .................................................................................................................................. 77 JERNIGAN......................................................................................................................... -

The Early Tudors : Henry VII.: Henry VIII

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES ^^. A Epochs of Modern History EDITED BY EDWARD E. MORRIS, M.A., J. SURTEES PHILLPOTTS, B.C.L. AND C. COLBECK, M.A. THE EARLY TUDORS REV. C. E. MOBERLY EPOCHS OF MODERN HISTORY THE EARLY TUDORS HENRY VII.: HENRY VIII. BY THE REV. C. E. MOBERLY, M.A. LATE A MASTER IN RUGBY SCHOOL WITH MAPS AND PLANS NEW YORK CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS 1887 PA PREFACE As the plan of works in this Series does not allow of systematic references at the foot of the pages to larger and more detailed histories of the period, it may be well to mention here a few of the books which are likely to be most useful to those who wish to study it more fully. So far as these are complete histories, they must be chiefly modern, as the age was not fertile in contemporary narratives. Thus for Richard III.'s time Mr. Gairdner's excellent Life of that king should be studied, with its appendix on Warbeck; for Henry VII. Lord Bacon's Life, which has been carefully edited for the Cambridge Univer- sity Press by Mr. Lumby. The Stanhope Essay by Mr. Williamson on the ' Foreign Commerce of Eng- land under the Tudors ' gives ample details on this subject in very small compass; and the religious movement from 1485 to 1509 is described to perfec- tion in Mr. Seebohm's delightful work on Colet, Erasmus, and More, and in Cooper's Life of the Lady Margaret. For Henry VIII. -

Bulletin Magazine of the Richard III Society

Ricardian Bulletin Magazine of the Richard III Society ISSN 0308 4337 December 2010 Ricardian December 2010 Bulletin Contents 2 From the Chairman 3 Annual General Meeting 2010 12 Bosworth 2010: commemoration and commerce 14 Obituary: Carole Rike 15 What shall we tell the children? 16 Study weekend April 2011: the rise and fall of the de la Poles 18 Other Society News and Notices 20 News and Reviews 27 Media Retrospective 31 The Lady Herself: the Westminster Abbey memorial to Anne Neville, by Peter Hammond 33 Edward’s younger brother, by Peter Hammond 35 The Manor of the More revisited, by Heather Falvey 36 Did Perkin Warbeck’s mercenaries introduce syphilis into the UK?, by Peter Stride 39 Medieval jokes and fables, part 1, by Heather Falvey 41 Breath fresheners, fifteenth-century style, by Tig Lang 42 Reservations on Kenilworth, by Geoffrey Wheeler 44 Correspondence 48 The Barton Library 50 Reports on Society Events: 50 A Literary Convention in Sydney, by Leslie McCawley 52 Visit to Tewkesbury, by Jo Quarcoopome 54 The Yorkshire Branch’s fiftieth anniversary 56 Future Society events 57 Branches and Groups 63 New Members and Recently Deceased Members 64 Calendar Contributions Contributions are welcomed from all members. All contributions should be sent to Lesley Boatwright. Bulletin Press Dates 15 January for March issue; 15 April for June issue; 15 July for September issue; 15 October for December issue. Articles should be sent well in advance. Bulletin & Ricardian Back Numbers Back issues of The Ricardian and the Bulletin are available from Judith Ridley. If you are interested in obtaining any back numbers, please contact Mrs Ridley to establish whether she holds the issue(s) in which you are interested. -

Descendants of JOHN PLANTAGENET V1

JOHN I PLANTAGENET Isabella of ANGOULEME Born: 1167 Born: 1188 Died: 1216 Died: 1246 HENRY III Eleanor of PROVENCE richard PLANTAGENET Isabel MARSHALL Llywelyn the Great OF WALES Joan PLANTAGENET Isabella PLANTAGENET William 2nd MARSHAL Eleanor PLANTAGENET Simon 6th DE MONTFORT Born: 1207 Born: 1223 Born: 5 Jan 1209 in Winchester Born: in PEMBROKE Castle Born: 1223 Born: 1215 Died: 1272 Died: 1291 Castle Marr: 1204 Died: 1275 Died: 2 Apr 1272 in Berhamstead Died: 1282 in Executed Castle Eleanor of CASTILLE EDWARD I PLANTAGENET Margaret of FRANCE PLANTAGENET John OF CORNWALL Isabella OF CORNWALL Henry OF ALMAIN Nicholas OF CORNWALL Henry DE MONTFORT Simon the Younger (7th) DE Amaury DE MONTFORT Guy DE MONTFORT Margherita ALDOBRANDESCA Born: 1241 Born: 1239 Born: 1279 PLANTAGENET PLANTAGENET PLANTAGENET PLANTAGENET Born: 1238 MONTFORT Born: 1243 Born: 1244 Died: 1301 Died: 1307 Died: 1318 Died: in Reading Abbey Died: in Reading Abbey Died: 1265 Born: 1240 Died: 1301 Died: 1288 Died: 1271 Isabella OF FRANCE EDWARD II PLANTAGENET Margaret OF FRANCE Katherine PLANTAGENET Joanna PLANTAGENET John PLANTAGENET Henry PLANTAGENET Henry 3rd DE BAR Eleanor PLANTAGENET Juliana PLANTAGENET Gilbert DE CLARE Joan PLANTAGENET Ralph de MONTHERMER Alphonso PLANTAGENET John 2nd BRABANT Margaret PLANTAGENET Berengaria PLANTAGENET Mary PLANTAGENET John 1st,Count of HOLLAND Elizabeth PLANTAGENET Humphrey de Bohun, Earl of Thomas of Brotherton Edmund of WOODSTOCK Margaret WAKE Roman ORSINI Anastasia DE MONTFORT Pietro DI VICO tomasina DE MONTFORT Born: 1284 Born: 1279 Born: 1264 Born: 1265 Born: 1266 Born: 1268 Born: 1269 Born: 1271 Died: 1230 Born: 1269 Born: 1273 Born: 1275 Born: 1276 Born: 1279 Marr: 1297 Born: 1282 HEREFORD. -

Henry VIII and the Irish Political Nation: an Assessment of Tudor Imperial Kingship in 16Th Century Ireland Emily Schwartz Union College - Schenectady, NY

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2015 Henry VIII and the Irish Political Nation: An Assessment of Tudor Imperial Kingship In 16th Century Ireland Emily Schwartz Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the European History Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation Schwartz, Emily, "Henry VIII and the Irish Political Nation: An Assessment of Tudor Imperial Kingship In 16th Century Ireland" (2015). Honors Theses. 387. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/387 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Henry VIII and the Irish Political Nation: An Assessment of Tudor Imperial Kingship In 16th Century Ireland By Emily Schwartz Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in the Department of History Union College June 2015 Introduction Ireland in the 16th century was by far the most self-governed domain under the authority of King Henry VIII. Within Ireland there were two distinct groups of people, the Gaelic Irish and the Anglo-Irish, whose cultural differences divided the island into two distinct political nations. The majority of Ireland was dominated by Gaelic Irish lordships. Gaelic Irish lords recognized the English king as their overlord, but followed Gaelic customs and laws within their lordships. The small sphere of English influence in Ireland was reduced even more by the political hegemony of the Anglo-Irish magnates.