Transnational Hong Kong–Style Stunt Work And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Actor Behind the Camera

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2016 The Actor Behind the Camera Zechariah H. Pierce Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Acting Commons, and the Performance Studies Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/4113 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ACTOR BEHIND THE CAMERA A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University by ZECHARIAH HENRY PIERCE Bachelor of Arts, Theatre, 2009 Director: DR. AARON ANDERSON Associate Chair of the Department of Theatre Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia May 2016 !ii Acknowledgement I am incredibly grateful to my family, to whom without their undying support, graduate school would not be possible. Thanks to my in-laws for your gracious hospitality and loving care, my wife for your strength in defending the homestead, and my children for your endless supply of love and entertainment. You are the reason I am where I am. To Dr. Aaron Anderson, for your encouragement and inspiration in exploring the unknown and crossing into uncharted territory. I hope to find as much success in bringing theatrical arts to all walks of life, and still have time to be a rockstar dad. To my students, actors, and producers: thank you for your patience, your trust, and your willingness to let me experiment with my identity in new roles. -

WALLY CROWDER 2ND UNIT DIRECTOR/STUNT COODINATOR [email protected]

WALLY CROWDER 2ND UNIT DIRECTOR/STUNT COODINATOR [email protected] MOTION PICTURES 2015 Monster Trucks (Stunt Performer) 2015 Kidnap (Assistant Stunt Coordinator) 2015 Self/less (Stunt Driver) 2015 Furious Seven (Stunt Driver) 2014 Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day (Utility Stunts) 2014 The Barber (Stunt Driver) 2014 Let’s Be Cops (Stunt Driver/Stunts) 2012 This is 40 (Stunt Driver) 2011 Jeff, Who Lives at Home (Stunts/Actor-Fisherman) 2011 Larry Crowne (Stunts) 2010 Uncle Nigel (Stunt Coordinator) 2009 A Christmas Carol (Stunts) 2009 Angels & Demons (Stunt Performer) 2009 12 Rounds (Stunt Performer/Actor-Streetcar Conductor) 2009 The Smell of Success (Stunts) 2006 The Last Time (Stunt Coordinator) 2005 Red Eye (Utility Stunts) 2005 The Dark (Stunt Coordinator) 2003 Basic (Stunts) 2003 House of 1000 Corpses (Stunt Performer) 2003 Old School (Stunts) 2003 War Stories (Stunt Coordinator) 2003 The Street Lawyer (Stunt Coordinator) 2002 Women vs. Men (Stunt Coordinator) 2002 Outta Time (Stunts) 2001 Rock Star (Stunts) 2001 Training Day (Stunts) 2001 Lying in Wait (Stunt Performer) 2001 Double Take (Stunts) 2000 The Adventures of Rocky & Bullwinkle (Stunts) 2000 Hot Boyz (Stunts) 1999 Avalon: Beyond the Abyss (Stunt Coordinator) 1999 House on Haunted Hill (Stunts) 1999 One Last Score (If…Dog…Rabbit) (Stunts) 1999 NetForce (Stunt Coordinator) 1998 The Siege (Stunt Performer) 1998 With Friends Like These… (Stunt Coordinator) 1998 Point Blank (Stunts) 1997 Acts of Betrayal (Stunts) 1997 Gone Fishin’ (Stunts) 1997 -

Resume Ryan Tarran

Ryan Tarran Stunt Actor [email protected] +614 10 697 926 Stunt Double for: Chris Hemsworth Jason Momoa Dolph Lundgren Nikolaj Coster-Waldau Alexander England TITLE YEAR ROLE Feature Films Occupation: Rainfall 2018 Stunt Performer Aquaman 2018 Stunt Double: Jason Momoa / Aquaman Stunt Double: Dolph Lundgren / King Nereus Mortal Engines 2018 Stunt Performer Thor: Ragnarok 2017 Stunt Double: Chris Hemsworth / Thor Stunt Double: The Hulk Gladiator #2 - “Roscoe” Alien: Covenant 2017 Stunt Double: Alexander England / Ankor Pirates of the Caribbean: 2017 Stunt Performer Dead Men Tell No Tales Hacksaw Ridge 2016 Stunt Performer The Osiris Child 2016 Stunt Double: Ian Roberts Gods of Egypt 2016 Stunt Double: Alexander England / Mnevis Stunt Double: Nikolaj Coster- Waldau / Horus Truth 2015 Stunt Performer Mad Max: Fury Road 2015 Stunt Performer Infinite 2015 Stunt Double: Luke Ford The Hobbit: 2014 Stunt Performer / “Orc” The Battle of the Five Armies Wyrmwood: Road to the Dead 2014 Stunt Performer The Wolverine 2013 Utility Stunts Around the Block 2012 Stunt Performer From Sydney with Love 2011 Stunt Perfomer Short Films Busted 2015 “Kick Boxer” Sick 2013 Stunt Performer The Gift 2013 “The Beast” Zombie Beaters 2013 Stunt Performer TV Series Frontier - Season 3 2018 “Wadlow” Core Stunt Performer A Place to Call Home 2016 Fight Trainer The Code 2016 Stunt Performer Old School 2014 “The Cobra” Behind Mansion Walls 2013 “Peter Dabish” Love Child 2013 Stunt Performer Power Games 2013 Stunt Performer Underbelly: Razor 2012 Stunt Performer Home and Away 2012 -2015 Stunt Performer Underbelly: Badness 2011 “Huge Wharfie” Wild Boys 2011 Stunt Performer Bikie Wars: Brothers in Arms 2011 Stunt Performer Houso’s 2010 Stunt Performer TV Commercials Sensis 2015 Stunt Performer NRL 2013 NRL Footballer double Sporting Bet 2012 NFL Player Stunt Performer Lexus 2012 Stunt Performer Nestle Kit Kat 2011 Stunt Jet Skier Live Shows Spiderman: Live Dubai 2011 “Electro” Spiderman: Live India 2010 “Electro” . -

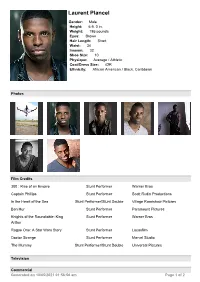

Laurent Plancel

Laurent Plancel Gender: Male Height: 6 ft. 0 in. Weight: 195 pounds Eyes: Brown Hair Length: Short Waist: 34 Inseam: 32 Shoe Size: 10 Physique: Average / Athletic Coat/Dress Size: 42R Ethnicity: African American / Black, Caribbean Photos Film Credits 300 : Rise of an Empire Stunt Performer Warner Bros Captain Phillips Stunt Performer Scott Rudin Productions In the Heart of the Sea Stunt Performer/Stunt Double Village Roadshow Pictures Ben Hur Stunt Performer Paramount Pictures Knights of the Roundtable: King Stunt Performer Warner Bros Arthur Rogue One: A Star Wars Story Stunt Performer Lucasfilm Doctor Strange Stunt Performer Marvel Studio The Mummy Stunt Performer/Stunt Double Universal Pictures Television Commercial Generated on 10/05/2021 01:56:56 am Page 1 of 2 Stage Music Videos Motion Capture Guild Affiliations British Stunt Register Stunt Teams Stunt Skills Stunt Skills: Ratchets, High Fall, Air Rams, Martial Artist, Wire Work, Car Hits, Motion Capture, Martial Arts: Kung Fu, Martial Arts: Tae Kwon Do, Martial Arts: Wushu, Weapons: Guns, Weapons: Knife, Weapons: Staff, Weapons: Nunchaku, Weapons: Katana, Chinese Swords: Dao, Chinese Swords: Dadao, Chinese Swords: Niuweidao, Tumbling ~ Basic, Martial Arts: Black Belt, Descender, Weapons: Broadsword, Weapons: Smallsword, Bridge Jumping, Stage Fighting, Martial Arts: Kick Boxing, Weapons: Pistol, Martial Arts: Taekwondo Athletic Skills: Boxing , Cycling, Gymnastics, Martial Arts, Soccer, Acrobat, Gymnastics: Fast-Track /Track Accents: British, French, Jamaican, African Spoken Languages: -

Ralph Story Outtakes and Television Programs 0249

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt5v19s1rt No online items Finding Aid of Ralph Story outtakes and television programs 0249 Finding aid prepared by Rebecca Hirsch and Nick Hazelton The processing of this collection and the creation of this finding aid was funded by the generous support of the Council on Library and Information Resources. USC Libraries Special Collections Doheny Memorial Library 206 3550 Trousdale Parkway Los Angeles, California, 90089-0189 213-740-5900 [email protected] 2011 Finding Aid of Ralph Story 0249 1 outtakes and television programs 0249 Title: Ralph Story outtakes and television programs Collection number: 0249 Contributing Institution: USC Libraries Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 261.0 linear ft.286 film reel boxes, 1 banker's box Date (inclusive): 1964-1972 Abstract: The collection includes outtake reels from the television show Ralph Story's Los Angeles and footage (some including sound) from the 1971-1972 season of the show Story in Hollywood. creator: Story, Ralph Preferred Citation [Box/folder# or item name], Ralph Story outtakes and television programs, Collection no. 0249, Regional History Collections, Special Collections, USC Libraries, University of Southern California Conditions Governing Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE. Advance notice required for access. Related Archival Materials The Ralph Story papers, 1940-2007. UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division. Collection number: 867. Acquisition The collection was given to the University of Southern California by Ralph Snyder Story on December 17, 1991. Conditions Governing Use All requests for permission to use film must be submitted in writing to the Manuscripts Librarian. -

Eric Sweeney

Eric Sweeney Gender: Male Service: (818) 769-1777 Height: 5 ft. 10 in. Mobile: (818) 439-4077 Weight: 165 pounds E-mail: [email protected] Eyes: Blue Web Site: http://www.imdb.com/... Hair Length: Short Waist: 32 Inseam: 30 Shoe Size: 9.5 Physique: Athletic Coat/Dress Size: 40R Ethnicity: Caucasian / White, Eastern European Unique Traits: TATTOOS (Don't Have Them) Photos Film Credits Television Criminal Minds Stunt double (Morgan McClellan) Tom Elliot Shameless Stunt actor Eddie Perez Sharknado 2 Stunts Sean Christopher New Girl (2 episodes) Stunt double (Jullian Morris) (Max Jimmy Sharp Greenfield) How to Get Away with Murder Stunt double (Charlie Weber) Peewee Piemonte The Mindy Project Stunt double (Adam Pally) Chris O'Hara Scandal Stunt double (George Newbern) Don Ruffin Scorpion (3 episodes) Stunt double (Eddie Kaye Thomas) Hugh O'Brien American Horror Story Stunt double (Wes Bentley) Jimmy Sharp Generated on 09/29/2021 02:49:42 am Page 1 of 3 Helena Barrett Future Man Stunt double (Patrick Carlyle) Mike Gaines Making Friends Stunt double (Jonny Sweet) Al Jones Stay Stunt actor Pat Romano Commercial Stage Music Videos Motion Capture Guild Affiliations SAG / AFTRA Stunt Teams No Affiliation at this time. Stunt Skills Stunt Skills: Ratchets, Trampoline, High Fall, Squibs, Air Rams, Precision Driving, Fight-Guy/Gal - General, Reactions, Free-Running / Parkour, Wave Runner, Wire Work, Weapons ~ General, Jet Skiing, Car Hits, I Ground Pound, Motion Capture, Dialogue, Stunt Driving, Driving: 180's, Driving: 360's, Driving: 90 Degree Box Park, -

Download Heroic Grace: the Chinese Martial Arts Film Catalog (PDF)

UCLA Film and Television Archive Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office in San Francisco HEROIC GRACE: THE CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FILM February 28 - March 16, 2003 Los Angeles Front and inside cover: Lau Kar-fai (Gordon Liu Jiahui) in THE 36TH CHAMBER OF SHAOLIN (SHAOLIN SANSHILIU FANG ) present HEROIC GRACE: THE CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FILM February 28 - March 16, 2003 Los Angeles Heroic Grace: The Chinese Martial Arts Film catalog (2003) is a publication of the UCLA Film and Television Archive, Los Angeles, USA. Editors: David Chute (Essay Section) Cheng-Sim Lim (Film Notes & Other Sections) Designer: Anne Coates Printed in Los Angeles by Foundation Press ii CONTENTS From the Presenter Tim Kittleson iv From the Presenting Sponsor Annie Tang v From the Chairman John Woo vi Acknowledgments vii Leaping into the Jiang Hu Cheng-Sim Lim 1 A Note on the Romanization of Chinese 3 ESSAYS Introduction David Chute 5 How to Watch a Martial Arts Movie David Bordwell 9 From Page to Screen: A Brief History of Wuxia Fiction Sam Ho 13 The Book, the Goddess and the Hero: Sexual Bérénice Reynaud 18 Aesthetics in the Chinese Martial Arts Film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon—Passing Fad Stephen Teo 23 or Global Phenomenon? Selected Bibliography 27 FILM NOTES 31-49 PROGRAM INFORMATION Screening Schedule 51 Print & Tape Sources 52 UCLA Staff 53 iii FROM THE PRESENTER Heroic Grace: The Chinese Martial Arts Film ranks among the most ambitious programs mounted by the UCLA Film and Television Archive, taking five years to organize by our dedicated and intrepid Public Programming staff. -

The Phenomenological Aesthetics of the French Action Film

Les Sensations fortes: The phenomenological aesthetics of the French action film DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Alexander Roesch Graduate Program in French and Italian The Ohio State University 2017 Dissertation Committee: Margaret Flinn, Advisor Patrick Bray Dana Renga Copyrighted by Matthew Alexander Roesch 2017 Abstract This dissertation treats les sensations fortes, or “thrills”, that can be accessed through the experience of viewing a French action film. Throughout the last few decades, French cinema has produced an increasing number of “genre” films, a trend that is remarked by the appearance of more generic variety and the increased labeling of these films – as generic variety – in France. Regardless of the critical or even public support for these projects, these films engage in a spectatorial experience that is unique to the action genre. But how do these films accomplish their experiential phenomenology? Starting with the appearance of Luc Besson in the 1980s, and following with the increased hybrid mixing of the genre with other popular genres, as well as the recurrence of sequels in the 2000s and 2010s, action films portray a growing emphasis on the importance of the film experience and its relation to everyday life. Rather than being direct copies of Hollywood or Hong Kong action cinema, French films are uniquely sensational based on their spectacular visuals, their narrative tendencies, and their presentation of the corporeal form. Relying on a phenomenological examination of the action film filtered through the philosophical texts of Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Paul Ricoeur, Mikel Dufrenne, and Jean- Luc Marion, in this dissertation I show that French action cinema is pre-eminently concerned with the thrill that comes from the experience, and less concerned with a ii political or ideological commentary on the state of French culture or cinema. -

Critical Study on History of International Cinema

Critical Study on History of International Cinema *Dr. B. P. Mahesh Chandra Guru Professor, Department of Studies in Communication and Journalism, University of Mysore, Manasagangotri Karnataka India ** Dr.M.S.Sapna ***M.Prabhudevand **** Mr.M.Dileep Kumar India ABSTRACT The history of film began in the 1820s when the British Royal Society of Surgeons made pioneering efforts. In 1878 Edward Muybridge, an American photographer, did make a series of photographs of a running horse by using a series of cameras with glass plate film and fast exposure. By 1893, Thomas A. Edison‟s assistant, W.K.L.Dickson, developed a camera that made short 35mm films.In 1894, the Limiere brothers developed a device that not only took motion pictures but projected them as well in France. The first use of animation in movies was in 1899, with the production of the short film. The use of different camera speeds also appeared around 1900 in the films of Robert W. Paul and Hepworth.The technique of single frame animation was further developed in 1907 by Edwin S. Porter in the Teddy Bears. D.W. Griffith had the highest standing among American directors in the industry because of creative ventures. The years of the First World War were a complex transitional period for the film industry. By the 1920s, the United States had emerged as a prominent film making country. By the middle of the 19th century a variety of peephole toys and coin machines such as Zoetrope and Mutoscope appeared in arcade parlors throughout United States and Europe. By 1930, the film industry considerably improved its technical resources for reproducing sound. -

100 Per Cent Jackie Chan : the Essential Companion Pdf, Epub, Ebook

100 PER CENT JACKIE CHAN : THE ESSENTIAL COMPANION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jackie Chan | 160 pages | 01 Sep 2003 | Titan Books Ltd | 9781840234916 | English | London, United Kingdom 100 Per Cent Jackie Chan : The Essential Companion PDF Book Its really amazing and a lot of fun to watch just for the choreography aspect. Visit store. What surprised me the most is that Jackie is not the straight-forward good-guy like in most of his films though it's hard to tell at times. Reuse this content opens in new window. He began producing records professionally in the s and has gone on to become a successful singer in Hong Kong and Asia. Awards won. Both Jackie and Alan go out into the hall and bump into May, and Jackie has to cover his tracks by pretending that Alan knows that Lorelei is in Jackie's bedroom. To tell you the truth I hardly remember this film. Ones opinions to reserve I am Jackie Chan : some other viewers should be able to determine in regards to publication. Was this review helpful? Joan Lin , a Taiwanese actress. Payment methods. And all of that unnecessary violent effort is only to kidnap someone in order to make the main character do something for them that they don't want to pay for. This is an acceptable action movie distinguished by nicely cinematography of the spectacular sequences , and contains agreeable sense of humor as well as previous entries. People who viewed this item also viewed. The visuals are memorable. Jackie starting an unforgettable fight with the evil monks in a spacious refectory. -

The Fight Master, January 1986, Vol. 9 Issue 1

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Fight Master Magazine The Society of American Fight Directors 1-1986 The Fight Master, January 1986, Vol. 9 Issue 1 The Society of American Fight Directors Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/fight Part of the Acting Commons, Other Theatre and Performance Studies Commons, Performance Studies Commons, and the Theatre History Commons American Fencers Supply Co 1180 Folsom Street San Francisco CA 94103 415/863-7911 UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA, LAS VEGAS JOURNAL OF THE SOCIETY OF AMERICAN FIGHT DIRECTORS January 1986 Volume IX number 1 • 6 SOAP FIGHTS by J. Allen Suddeth • 12 STAGING REALISTIC VIOLENCE by David Leong • 16 ADVANCED FIGHT WORKSHOP by Joseph Martinez • 25 WEAPON NOTES by Michael Cawelti • 26 SO YOU WANT TO BE IN PIICTL,RES PiICTL-RES by David Boushey • 27 From Good to Bad in Shakespeare anc Sheridan • 27 Chinese Weapons •3 Editor's Comments •3 President's Report •4 Vice President's Report •4 Treasurer's Report • 5 Workshop Report • 32 Points of Interest • 33 Society News • 28 Letters to the Editor THE FIGHT MASTER SOCIETY OF AMERICAN FIGHT DIRECTORS President Joseph Martinez Journal of the Society of American Fight Directors Vice President Drew Fracher Treasurer David Boushey Editor Linda Carlyle McCollum Secretary Linda McCo/lum McCollum Associate Editor Olga Lyles Contributing Editors David Boushey !"r:eTt:e So-c:e!}' Soc,:ey ofOf American Fight Directors was founded in May, 197Z It is a non•non· Joseph Martinez profiTprofn organrzation organization whose aim is toTO promote the art of fight choreography as Graphics Akiko Onaka an .:ntegra'integra! panpa.11 of the entertainment industry. -

Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity

Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity Aesthetics, Representation, Circulation Man-Fung Yip Hong Kong University Press Th e University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © 2017 Hong Kong University Press ISBN 978-988-8390-71-7 (Hardback) All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any infor- mation storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. An earlier version of Chapter 2 “In the Realm of the Senses” was published as “In the Realm of the Senses: Sensory Realism, Speed, and Hong Kong Martial Arts Cinema,” Cinema Journal 53 (4): 76–97. Copyright © 2014 by the University of Texas Press. All rights reserved. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Paramount Printing Co., Ltd. in Hong Kong, China Contents Acknowledgments viii Notes on Transliteration x Introduction: Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity 1 1. Body Semiotics 24 2. In the Realm of the Senses 56 3. Myth and Masculinity 85 4. Th e Diffi culty of Diff erence 115 5. Marginal Cinema, Minor Transnationalism 145 Epilogue 186 Filmography 197 Bibliography 203 Index 215 Introduction Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity Made at a time when confi dence was dwindling in Hong Kong due to a battered economy and in the aft ermath of the SARS epidemic outbreak,1 Kung Fu Hustle (Gongfu, 2004), the highly acclaimed action comedy by Stephen Chow, can be seen as an attempt to revitalize the positive energy and tenacious resolve—what is commonly referred to as the “Hong Kong spirit” (Xianggang jingshen)—that has allegedly pro- pelled the city’s amazing socioeconomic growth.