Working Children in Curvelo, Minas Gerais, Brazil Marcia Mikulak University of North Dakota, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Currency and Coin Management

The George Washington University WASHINGTON DC IBI - INSTITUTE OF BRAZILIAN BUSINESS AND PUBLIC MANAGEMENT ISSUES The Minerva Program Fall 2004 CURRENCY AND COIN MANAGEMENT: A COMPARISON OF AMERICAN AND BRAZILIAN MODELS Author: Francisco José Baptista Campos Advisor: Prof. William Handorf Washington, DC – December 2004 AKNOWLEDGMENTS ? to Dr. Gilberto Paim and the Instituto Cultural Minerva for the opportunity to participate in the Minerva Program; ? to the Central Bank of Brazil for having allowed my participation; ? to Professor James Ferrer Jr., Ph.D., and his staff, for supporting me at the several events of this Program; ? to Professor William Handorf, Ph.D., for the suggestions and advices on this paper; ? to Mr. José dos Santos Barbosa, Head of the Currency Management Department, and other Central Bank of Brazil officials, for the information on Brazilian currency and coin management; ? to the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and, in particular, to Mr. William Tignanelli and Miss Amy L. Eschman, who provided me precious information about US currency and coin management; ? to Mr. Peter Roehrich, GWU undergraduate finance student, for sharing data about US crrency and coin management; and, ? to Professor César Augusto Vieira de Queiroz, Ph.D., and his family, for their hospitality during my stay in Washington, DC. 2 ? TABLE OF CONTENTS I – Introduction 1.1. Objectives of this paper 1.2. A brief view of US and Brazilian currency and coin II – The currency and coin service structures in the USA and in Brazil 2.1. The US currency management structure 2.1.1. The legal basis 2.1.2. The Federal Reserve (Fed) and the Reserve Banks 2.1.3. -

Economic Impacts of Tourism in Protected Areas of Brazil

Journal of Sustainable Tourism ISSN: 0966-9582 (Print) 1747-7646 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsus20 Economic impacts of tourism in protected areas of Brazil Thiago do Val Simardi Beraldo Souza, Brijesh Thapa, Camila Gonçalves de Oliveira Rodrigues & Denise Imori To cite this article: Thiago do Val Simardi Beraldo Souza, Brijesh Thapa, Camila Gonçalves de Oliveira Rodrigues & Denise Imori (2018): Economic impacts of tourism in protected areas of Brazil, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, DOI: 10.1080/09669582.2017.1408633 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1408633 Published online: 02 Jan 2018. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsus20 Download by: [Thiago Souza] Date: 03 January 2018, At: 03:26 JOURNAL OF SUSTAINABLE TOURISM, 2017 https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1408633 Economic impacts of tourism in protected areas of Brazil Thiago do Val Simardi Beraldo Souzaa, Brijesh Thapa b, Camila Goncalves¸ de Oliveira Rodriguesc and Denise Imorid aChico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation and School of Natural Resources and Environment, EQSW, Complexo Administrativo, Brazil & University of Florida, Brasilia, DF, Brazil; bDepartment of Tourism, Recreation & Sport Management, FLG, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA; cDepartment of Business and Tourism, Rua Marquesa de Santos, Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil; dDepartment of Economy, Rua Comendador Miguel Calfat, University of S~ao Paulo, S~ao Paulo, SP, Brazil ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Protected areas (PAs) are globally considered as a key strategy for Received 31 October 2016 biodiversity conservation and provision of ecosystem services. -

Item 05.1 Vallourec Florestal Ltda.Pdf

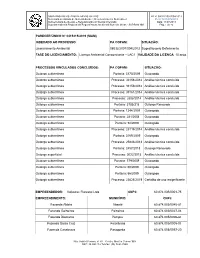

GOVERNO DO ESTADO DE MINAS GERAIS PA nº 08032/2007/004/2013 Secretaria de Estado de Meio Ambiente e Desenvolvimento Sustentável PU no 0415415/2019 Subsecretaria de Gestão e Regularização Ambiental Integrada Data: 11/07/2019 Superintendência Regional de Regularização Ambiental Norte de Minas - SUPRAM NM Pág. 1 de 94 PARECER ÚNICO Nº 0415415/2019 (SIAM) INDEXADO AO PROCESSO: PA COPAM: SITUAÇÃO: Licenciamento Ambiental 08032/2007/004/2013 Sugestão pelo Deferimento FASE DO LICENCIAMENTO: Licença Ambiental Concomitante – LAC1 VALIDADE DA LICENÇA: 10 anos PROCESSOS VINCULADOS CONCLUÍDOS: PA COPAM: SITUAÇÃO: Outorga subterrânea Portaria: 3170/2009 Outorgado Outorga subterrânea Processo: 33158/2014 Análise técnica concluída Outorga subterrânea Processo: 33159/2014 Análise técnica concluída Outorga subterrânea Processo: 33161/2014 Análise técnica concluída Outorga subterrânea Processo: 2808/2014 Análise técnica concluída Outorga subterrânea Portaria: 3785/218 Outorga Renovada Outorga subterrânea Portaria: 1244/2009 Outorgado Outorga subterrânea Portaria: 281/2008 Outorgado Outorga subterrânea Portaria: 52/2009 Outorgado Outorga subterrânea Processo: 25119/2014 Análise técnica concluída Outorga subterrânea Portaria: 3169/2009 Outorgado Outorga subterrânea Processo: 25846/2013 Análise técnica concluída Outorga subterrânea Portaria: 2457/2018 Outorga Renovada Outorga superficial Processo: 3022/2015 Análise técnica concluída Outorga subterrânea Portaria: 379/2009 Outorgado Outorga subterrânea Portaria: 60/2009 Outorgado Outorga subterrânea Portaria: -

Soybean Transportation Guide: Brazil 2018 (Pdf)

Agricultural Marketing Service July 2019 Soybean Transportation Guide: BRAZIL 2018 United States Department of Agriculture Marketing and Regulatory Programs Agricultural Marketing Service Transportation and Marketing Program July 2019 Author: Delmy L. Salin, USDA, Agricultural Marketing Service Graphic Designer: Jessica E. Ladd, USDA, Agricultural Marketing Service Preferred Citation Salin, Delmy. Soybean Transportation Guide: Brazil 2018. July 2019. U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Agricultural Marketing Service. Web. <http://dx.doi.org/10.9752/TS048.07-2019> USDA is an equal opportunity provider, employer, and lender. 2 Contents Soybean Transportation Guide: Brazil 2018 . 4 General Information. 7 2018 Summary . 8 Transportation Infrastructure. 25 Transportation Indicators. 28 Soybean Production . 38 Exports. 40 Exports to China . 45 Transportation Modes . 54 Reference Material. 66 Photo Credits. 75 3 Soybean Transportation Guide: Brazil 2018 Executive Summary The Soybean Transportation Guide is a visual snapshot of Brazilian soybean transportation in 2018. It provides data on the cost of shipping soybeans, via highways and ocean, to Shanghai, China, and Hamburg, Germany. It also includes information about soybean production, exports, railways, ports, and infrastructural developments. Brazil is one of the most important U.S. competitors in the world oilseed market. Brazil’s competitiveness in the world market depends largely on its transportation infrastructure, both production and transportation cost, increases in planted area, and productivity. Brazilian and U.S. producers use the same advanced production and technological methods, making their soybeans relative substitutes. U.S soybean competitiveness worldwide rests upon critical factors such as transportation costs and infrastructure improvements. Brazil is gaining a cost advantage. However, the United States retains a significant share of global soybean exports. -

Polyethylene Terephthalate Resin from Brazil

A-351-852 Investigation Public Document E&C/Office VII: EB/KW September 17, 2018 MEMORANDUM TO: Gary Taverman Deputy Assistant Secretary for Antidumping and Countervailing Duty Operations, performing the non-exclusive functions and duties of the Assistant Secretary for Enforcement and Compliance FROM: James Maeder Associate Deputy Assistant Secretary for Antidumping and Countervailing Duty Operations performing the duties of Deputy Assistant Secretary for Antidumping and Countervailing Duty Operations SUBJECT: Issues and Decision Memorandum for the Final Affirmative Determination in the Less-Than-Fair-Value Investigation of Polyethylene Terephthalate Resin from Brazil I. SUMMARY The Department of Commerce (Commerce) determines that polyethylene terephthalate (PET) resin from Brazil is being, or is likely to be, sold in the United States at less than fair value, as provided in section 735 of the Tariff Act of 1930, as amended (the Act). The period of investigation is July 1, 2016, through June 30, 2017. We analyzed the comments of the interested parties. As a result of this analysis, and based on our findings at verification, we made certain changes to M&G Polimeros Brasil S.A.’s (MGP Brasil’s) margin calculation program with respect to packing expenses. In addition, we applied total facts otherwise available, with an adverse inference, to Companhia Integrada Textil de Pernambuco (Textil de Pernambuco). We recommend that you approve the positions described in the “Discussion of the Issues” section of this memorandum. Below is the complete list of the issues in this investigation on which we received comments from parties. Comment 1: Whether MGP Brasil’s Unverified Bank Charges Should Result in the Application of Adverse Facts Available. -

Lista De Classificados Para a Etapa Regional

Lista de Classificados para a Etapa Regional 1 – Classificados para Etapa Regional. Módulo I Basquete Feminino SRE Município Escola Curvelo Curvelo E.E. Major Antônio Salvo Diamantina Alvorada de Minas E.E. José Madureira Horta Montes Claros Montes Claros Centro Educacional Ímpar Pirapora Ponto Chique E.E. Professor Edilson Brandão Januária Varzelândia E.E. Padre José Silveira Centro de Educação e Cultura - Janaúba Janaúba CEC Basquete Masculino SRE Município Escola Instituto Pequeno Príncipe Curvelo Curvelo Expansão Diamantina Alvorada de Minas E.E. José Madureira Horta Montes Claros Montes Claros Centro Educacional Ímpar Colégio Nossa Senhora do Pirapora Pirapora Santíssimo Sacramento Januária Varzelândia E.E. Padre José Silveira Centro de Educação e Cultura - Janaúba Janaúba CEC Futsal Feminino SRE Município Escola E.M. Geralda Márcia Pereira Curvelo Três Marias Gonçalves Diamantina Capelinha E.E. Rosarinha Pimentinha Montes Claros E.E. Doutor Carlos Albuquerque Montes Claros Patis E.E. Francisco Andrade Pirapora Pirapora E.E. Coronel Ramos Januária Icaraí de Minas E.E. Manoel Tibério E.M. Madre Cândida Maria de Janaúba Janaúba Jesus Futsal Masculino SRE Município Escola E.M. Geralda Márcia Pereira Curvelo Três Marias Gonçalves Diamantina Capelinha E.E. Rosarinha Pimentinha Montes Claros Capitão Enéas E.E. José Patrício da Silveira E.E. José Natalino Boaventura Pirapora Pirapora Leite E.M. Carmem Maria Andrade Januária Itacarambi Nogueira E.E. Professor José Américo Janaúba Mato Verde Barbosa Handebol Feminino SRE Município Escola E.M. Geralda Márcia Pereira Curvelo Três Marias Gonçalves Diamantina Minas Novas E.E. Presidente Costa Silva Montes Claros Colégio Sólido Montes Claros Bocaiúva E.E. Professor Gastão Valle Colégio Nossa Senhora do Pirapora Pirapora Santíssimo Sacramento E.M. -

A Fourth Decade of Brazilian Democracy

INTRODUCTION Peter R. Kingstone and Timothy J. Power A Fourth Decade of Brazilian Democracy Achievements, Challenges, and Polarization IN 2009 THE Economist magazine celebrated Brazil’s meteoric rise as an emerging power with a cover featuring Rio de Janeiro’s mountaintop icon, “Christ the Redeemer,” taking off into the stratosphere. Four years later, with the economy in decline and protestors marching in the streets, the magazine again featured the Cristo, this time in a horrific nosedive, asking “Has Brazil blown it?” Brazil’s situation had deteriorated but still remained hopeful enough to allow the incumbent Workers’ Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores; PT) president Dilma Rousseff to win reelection in October 2014. Within months of her victory, however, the country was plunged even deeper into re- cession and was caught up in the sharpest and most polarizing political crisis in the young democracy’s history. In a short period, Brazil had moved from triumphant emerging power to a nation divided against itself. At the heart of the political crisis was the impeachment of Dilma, a process that began barely a year into her second term. Dilma’s reelection campaign had withstood declining economic performance and a rapidly widening cor- ruption investigation—the Lava Jato (car wash) scandal that ensnared dozens of leading business people and politicians, including many key PT figures, though not Dilma herself. In October 2015, the Federal Accounting Court (Tribunal de Contas da União; TCU) rejected Dilma’s budget accounts, having identified a series of practices that violated federal budget and fiscal 3 © 2017 University of Pittsburgh Press. All rights reserved. -

Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations

Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations Updated July 6, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46236 SUMMARY R46236 Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations July 6, 2020 Occupying almost half of South America, Brazil is the fifth-largest and fifth-most-populous country in the world. Given its size and tremendous natural resources, Brazil has long had the Peter J. Meyer potential to become a world power and periodically has been the focal point of U.S. policy in Specialist in Latin Latin America. Brazil’s rise to prominence has been hindered, however, by uneven economic American Affairs performance and political instability. After a period of strong economic growth and increased international influence during the first decade of the 21st century, Brazil has struggled with a series of domestic crises in recent years. Since 2014, the country has experienced a deep recession, record-high homicide rate, and massive corruption scandal. Those combined crises contributed to the controversial impeachment and removal from office of President Dilma Rousseff (2011-2016). They also discredited much of Brazil’s political class, paving the way for right-wing populist Jair Bolsonaro to win the presidency in October 2018. Since taking office in January 2019, President Jair Bolsonaro has begun to implement economic and regulatory reforms favored by international investors and Brazilian businesses and has proposed hard-line security policies intended to reduce crime and violence. Rather than building a broad-based coalition to advance his agenda, however, Bolsonaro has sought to keep the electorate polarized and his political base mobilized by taking socially conservative stands on cultural issues and verbally attacking perceived enemies, such as the press, nongovernmental organizations, and other branches of government. -

De Suor, Fumaça E Munha: a Atividade De Carvoejamento Em Curvelo/Mg1

DE SUOR, FUMAÇA E MUNHA: A ATIVIDADE DE CARVOEJAMENTO EM CURVELO/MG1 ÉRIKA DE CÁSSIA OLIVEIRA CAETANO2 1- Introdução O presente trabalho tem como objetivo analisar a dinâmica, os processos e as produções sociais decorrentes da atividade de carvoejamento no município de Curvelo/MG, numa reflexão interdisciplinar entre a Sociologia do Trabalho e a História Ambiental. A pesquisa foi realizada nos anos de 2005 a 2008, centrada numa análise do trabalho e dos trabalhadores do carvão. Tendo como pano de fundo a mudança na paisagem do município de Curvelo/MG do cerrado às pastagens e destas às florestas homogêneas, a análise do processo de trabalho e suas consequências para os trabalhadores desdobrou-se em uma preocupação com o aspecto ambiental dada a forma peculiar de ocupação e uso do espaço natural. A questão das carvoarias apresentou-se como um campo propício aos estudos socioambientais e, como a História Ambiental é um campo de pesquisa relativamente novo e em expansão, que busca compreender “corno os seres humanos foram, através dos tempos, afetados pelo seu ambiente natural e, inversamente, como eles afetaram esse ambiente e com que resultados” (WOSTER, 1991, p. 02) considerou-se a possibilidade de refletir o tema pautado nesta abordagem historiográfica. Ainda considera-se, conforme Duarte (2005, p. 32): “compreender a historicidade das relações entre a sociedade e a natureza pode, certamente, dar-nos instrumentos para assumir uma postura mais crítica frente aos debates sobre o ambiente”. Desta maneira, este estudo visa contribuir para uma compreensão mais nítida da mudança da paisagem do município de Curvelo/MG como um processo histórico de intervenção humana sobre o espaço natural. -

Brasilia, Brazil Destination Guide

Brasilia, Brazil Destination Guide Overview of Brasilia Situated atop the Brazilian highlands, Brasilia is the country's purpose-built capital and seat of government. Most visitors pass through Brasilia International Airport, one of the continent's major transport hubs, without bothering to view the city. And, sadly, it's true that the city can't compete with the allure of Brazil's more mainstream destinations. Nevertheless, Brasilia is recognised as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and is a major drawcard for architecture aficionados, who come to marvel at its artistic layout and monumental modernist buildings. Designed to recreate a utopian city, Brasilia has been nicknamed 'ilha da fantasia' or 'Fantasy Island'. The buildings serve as monuments to progress, technology and the promise of the future, and, against a backdrop of perpetually blue sky, their striking, bleached-white granite and concrete lines are wonderfully photogenic. Among the most famous of Brasilia's modernist structures are the Cathedral of Santuario Dom Bosco, the monolithic Palácio do Itamaraty, and the TV tower which, at 240 feet (72m), offers the best views in town. The famous Brazilian architect, Oscar Niemeyer, designed all of the original city's buildings, while the urban planner, Lucio Costa, did the layout. The central city's intersecting Highway Axis makes it resemble an aeroplane when viewed from above. Getting around the city is easy and convenient, as there is excellent public transport, but walking is not usually an option given the vast distances between the picturesque landmarks. Brasilia is located 720 miles (1,160km) from Rio de Janeiro and 626 miles (1,007km) from Sao Paulo. -

Município SRE ABADIA DOS DOURADOS SRE MONTE

LISTA DOS MUNICÍPIO DE MINAS GERAIS POR SUPERINTENDÊNCIA REGIONAL DE ENSINO (SER) Município SRE ABADIA DOS DOURADOS SRE MONTE CARMELO ABAETÉ SRE PARÁ DE MINAS ABRE CAMPO SRE PONTE NOVA ACAIACA SRE OURO PRETO AÇUCENA SRE GOVERNADOR VALADARES ÁGUA BOA SRE GUANHÃES ÁGUA COMPRIDA SRE UBERABA AGUANIL SRE CAMPO BELO ÁGUAS FORMOSAS SRE TEÓFILO OTONI ÁGUAS VERMELHAS SRE ALMENARA AIMORÉS SRE GOVERNADOR VALADARES AIURUOCA SRE CAXAMBU ALAGOA SRE CAXAMBU ALBERTINA SRE POUSO ALEGRE ALÉM PARAÍBA SRE LEOPOLDINA ALFENAS SRE VARGINHA ALFREDO VASCONCELOS SRE BARBACENA ALMENARA SRE ALMENARA ALPERCATA SRE GOVERNADOR VALADARES ALPINÓPOLIS SRE PASSOS ALTEROSA SRE POÇOS DE CALDAS ALTO CAPARAÓ SRE CARANGOLA ALTO JEQUITIBÁ SRE MANHUAÇU ALTO RIO DOCE SRE BARBACENA ALVARENGA SRE CARATINGA ALVINÓPOLIS SRE PONTE NOVA ALVORADA DE MINAS SRE DIAMANTINA AMPARO DO SERRA SRE PONTE NOVA ANDRADAS SRE POÇOS DE CALDAS ANDRELÂNDIA SRE BARBACENA ANGELÂNDIA SRE DIAMANTINA ANTÔNIO CARLOS SRE BARBACENA ANTÔNIO DIAS SRE CORONEL FABRICIANO ANTÔNIO PRADO DE MINAS SRE MURIAÉ ARAÇAÍ SRE SETE LAGOAS ARACITABA SRE BARBACENA ARAÇUAÍ SRE ARAÇUAÍ ARAGUARI SRE UBERLÂNDIA ARANTINA SRE JUIZ DE FORA ARAPONGA SRE PONTE NOVA ARAPORÃ SRE UBERLÂNDIA ARAPUÁ SRE PATOS DE MINAS ARAÚJOS SRE DIVINÓPOLIS ARAXÁ SRE UBERABA ARCEBURGO SRE SÃO SEBASTIÃO DO PARAÍSO ARCOS SRE DIVINÓPOLIS AREADO SRE POÇOS DE CALDAS ARGIRITA SRE LEOPOLDINA ARICANDUVA SRE DIAMANTINA ARINOS SRE UNAÍ ASTOLFO DUTRA SRE UBÁ ATALÉIA SRE TEÓFILO OTONI AUGUSTO DE LIMA SRE CURVELO BAEPENDI SRE CAXAMBU BALDIM SRE SETE LAGOAS BAMBUÍ SRE -

Complementação Do Processo De

Complementação do processo de tombamento da Casa Grande Exercício 2013 de acordo com a deliberação nº01/2009 Luz / MG Pasta Quadro1/2) (Pasta III Complementação do Dossiê de Tombamento da Casa Grande – Luz/Minas Gerais 2 Agostinho Carlos Oliveira – Prefeito Municipal de Luz 44 ÍNDICE 1. INTRODUÇÃO ............................................................................................................................................................... 3 2. PARECER DE TOMBAMENTO DO CONSELHO ........................................................................................................... 6 3. PLANTA DE DELIMITAÇÃO DO PERÍMETRO DE ENTORNO ...................................................................................... 7 4. LAUDO DE AVALIAÇÃO SOBRE O ESTADO DE CONSERVAÇÃO ............................................................................. 8 5. FICHA TÉCNICA ........................................................................................................................................................... 20 6. HISTÓRICO RETIFICADO DO MUNICÍPIO .................................................................................................................. 21 7. ERRATA ........................................................................................................................................................................ 44 Chefe de Setor da Prefeitura: Fabrício J. Camargos Silva Rubrica : Data: 11 / jan/ 2012 Complementação do Dossiê de Tombamento da Casa Grande – Luz/Minas Gerais 1. INTRODUÇÃO