The Memorial Chapel of the University of Glasgow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aberdeen History Trail the City Through Its Historical Times

Aberdeen History Trail The city through its historical times #aberdeentrails #aberdeentrails Aberdeen is bursting full of history! From its ancient origins to medieval burghs and King Robert The Bruce, from the Jacobite connections to the expansion in the Edwardian and Victorian times, the ‘Silver City by the Golden Sands’ has a long, important, and interesting history with many of its people contributing to the wider world. The city started out as three separate royal burghs – Old Aberdeen, New Aberdeen and Torry plus the parish of Woodside – which expanded and merged together to form the city as a whole. There was a major expansion in the Georgian, Edwardian and Victorian eras as the city made its first fortunes based on fishing, granite quarrying and shipbuilding and many of the grand buildings were built during these times. It also included the main thoroughfare, Union Street, which was raised up away from the mud and dirt and built on a series of bridges – it was such a major project it almost bankrupted the city! Enjoy exploring our beautiful city and finding out about its history! Picture Credits All images © Aberdeen City Council unless otherwise stated Introduction and all entries: This trail is extensively illustrated by period pictures from the Silver City Vault. The majority are from this source and we’re very grateful for their use and the help from this service. They are all used courtesy of Aberdeen City Libraries/Silver City Vault www.silvercityvault.org.uk 4: Used courtesy of the photographer © Roddy Millar. 14: Thomas Blake Glover courtesy Nagasaki Museum of History and Culture Left, New & Old Aberdeen maps: Details from Parson Gordon’s map of 1661. -

Challenges, Changes, Achievements a Celebration of Fifty Years of Geography at the University Plymouth Mark Brayshay

Challenges, Changes, Achievements A Celebration of Fifty Years of Geography at the University Plymouth Mark Brayshay Challenges, Changes, Achievements A Celebration of Fifty Years Challenges, Changes, Achievements A Celebration of Fifty Years of Geography at the University of Plymouth Mark Brayshay Challenges, Changes, Achievements A Celebration of Fifty Years of Geography at the University of Plymouth IV Challenges, Changes, Achievements A Celebration of Fifty Years of Geography at the University of Plymouth MARK BRAYSHAY University of Plymouth Press V VI Paperback edition first published in the United Kingdom in 2019 by University of Plymouth Press, Roland Levinsky Building, Drake Circus, Plymouth, Devon, PL4 8AA, United Kingdom. ISBN 978-1-84102-441-7 Copyright © Mark Brayshay and The School of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Plymouth, 2019 A CIP catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the author and The School of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Plymouth Printed and bound by Short Run Press Limited, Bittern Road, Sowton Industrial Estate, Exeter EX2 7LW This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

The Trinitarian Ecclesiology of Thomas F. Torrance

The Trinitarian Ecclesiology of Thomas F. Torrance Kate Helen Dugdale Submitted to fulfil the requirements for a Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Otago, November 2016. 1 2 ABSTRACT This thesis argues that rather than focusing on the Church as an institution, social grouping, or volunteer society, the study of ecclesiology must begin with a robust investigation of the doctrine of the Holy Trinity. Utilising the work of Thomas F. Torrance, it proposes that the Church is to be understood as an empirical community in space and time that is primarily shaped by the perichoretic communion of Father, Son and Holy Spirit, revealed by the economic work of the Son and the Spirit. The Church’s historical existence is thus subordinate to the Church’s relation to the Triune God, which is why the doctrine of the Trinity is assigned a regulative influence in Torrance’s work. This does not exclude the essential nature of other doctrines, but gives pre-eminence to the doctrine of the Trinity as the foundational article for ecclesiology. The methodology of this thesis is one of constructive analysis, involving a critical and constructive appreciation of Torrance’s work, and then exploring how further dialogue with Torrance’s work can be fruitfully undertaken. Part A (Chapters 1-5) focuses on the theological architectonics of Torrance’s ecclesiology, emphasising that the doctrine of the Trinity has precedence over ecclesiology. While the doctrine of the Church is the immediate object of our consideration, we cannot begin by considering the Church as a spatiotemporal institution, but rather must look ‘through the Church’ to find its dimension of depth, which is the Holy Trinity. -

Dr. James Ross Innes, Died 2Nd May, 1968

Dr. James Ross Innes, died 2nd May, 1968 102 Lepr'osy Review J ames Ross Innes M.D. ( EDINBURGH), D.T.M. ( LIVERPOOL) Editor, Leprosy Review, 1957-1968 Medical Secretary, LEPRA, 1957-1966 With the passing of Dr. James Ross Innes on Muir, who happened to be his travelling com 2nd May, 1968, at the age of 65, Leprosy Review panion on his voyage to India in 1928. As has lost a distinguished Editor and the cause of medical officer to the Khondwa Leper Asylum leprosy throughout the world is bereft of a wise and the Wadia Hospital of the Church of counsellor and advocate. Our deep sympathy Scotland Mission in Poona, India, he had every goes to his widow, who has herself for some opportunity of seeing the sad ravages of leprosy years been most active and efficient in the in the pre-sulphone days. conduct of the business side of the Review, and During leave in England in 1934, Ross Innes to his two daughters. took the course for the Diploma in Tropical It was as Medical Secretary of LEPRA that Medicine at the Liverpool School. He gained the he assumed the office of Editor, and after diploma, and also the Milne Medal as the most relinquishing the secretaryship in early 1966 distinguished student of his year. Within because of failing health, he continued as months, his thesis (on leprosy) for the M.D. of Editor; in fact, he had just seen the second issue Edinburgh University was accepted, 'with of 1968 offthe press when the call came. -

Can Scotland Still Call Itself a Fair Trade Nation?

Can Scotland still call itself a Fair Trade Nation? A report by the Scottish Fair Trade Forum JANUARY 2017 CAN SCOTLAND STILL CALL ITSELF A FAIR TRADE NATION? Scottish Fair Trade Forum Robertson House 152 Bath Street Glasgow G2 4TB +44 (0)141 3535611 www.sftf.org.uk www.facebook.com/FairTradeNation www.twitter.com/FairTradeNation [email protected] Scottish charity number SC039883 Scottish registered company number SC337384. Acknowledgements The Scottish Fair Trade Forum is very grateful for the help and advice received during the preparation of this report. We would like to thank everyone who has surveys and those who directly responded been involved, especially the Assessment to our personalised questionnaires: Andrew Panel members, Patrick Boase (social auditor Ashcroft (Koolskools Founding Partner), registered with the Social Audit Network UK Amisha Bhattarai (representative of Get Paper who chaired the Assessment Panel), Dr Mark Industry – GPI, Nepal), Mandira Bhattarai Hayes (Honorary Fellow in the Department of (representative of Get Paper Industry – GPI, Theology and Religion at Durham University, Nepal), Rudi Dalvai (President of the World Chair of the WFTO Appeals Panel and Fair Trade Organisation – WFTO), Patricia principal founder of Shared Interest), Penny Ferguson (Former Convener of the Cross Newman OBE (former CEO of Cafédirect and Party Group on Fair Trade in the Scottish currently a Trustee of Cafédirect Producers’ Parliament), Elen Jones (National Coordinator Foundation and Drinkaware), Sir Geoff Palmer at Fair Trade Wales), -

Glasgow Cinema Programmes 1908-1914

Dougan, Andy (2018) The development of the audience for early film in Glasgow before 1914. PhD thesis. https://theses.gla.ac.uk/9088/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] The development of the audience for early film in Glasgow before 1914 Andy Dougan Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Culture and Creative Arts College of Arts University of Glasgow May 2018 ©Andy Dougan, May 2018 2 In memory of my father, Andrew Dougan. He encouraged my lifelong love of cinema and many of the happiest hours of my childhood were spent with him at many of the venues written about in this thesis. 3 Abstract This thesis investigates the development of the audience for early cinema in Glasgow. It takes a social-historical approach considering the established scholarship from Allen, Low, Hansen, Kuhn et al, on the development of early cinema audiences, and overlays this with original archival research to provide examples which are specific to Glasgow. -

Archive Services: Annual Review 2013/14 1

Archive Services: Annual Review 2013/14 1. Overview of the year Our major achievements in support of the University Strategy this year are: Successfully applying to the Chancellor’s Fund to support the Campus Development initiative by capturing the architectural history of the University’s 172 buildings and presenting it as part of the University Story website. Enhancing the graduate attributes of 75 student interns from a diverse subject range and receiving a Learning & Teaching Fund award to investigate the potential for turning this into a core service to benefit students. Establishing a new partnership with the Centre for Battlefield Archaeology and the History subject area to ensure the University has an accurate and user-friendly dataset on which to base its Great War Commemoration activities. This work is supported by the Chancellors Fund for one year from March. The First Minister was among those to see the archive display at the Commonwealth Commemoration event marking the start of the First World War. Image: First Minister talks to staff and students about Glasgow University’s Great War. Securing National Manuscripts Conservation Trust funding to preserve and conserve our earliest shipbuilding drawings in the internationally important William Simons Collection. Sharing our knowledge by providing a Digital Preservation Traineeship as part of the Heritage Lottery Fund Skills for the Future Programme. This is in association with the University’s Digital Library Team and the Digital Preservation Coalition. Reaching over 2000 followers on Twitter, making us among the most followed Archive Services in the English speaking Higher Education sector. 2. Delivering excellent research 2.1 Enhancing research strengths In March we worked with Special Collections on a Research Inspiration event that was very well attended. -

Who, Where and When: the History & Constitution of the University of Glasgow

Who, Where and When: The History & Constitution of the University of Glasgow Compiled by Michael Moss, Moira Rankin and Lesley Richmond © University of Glasgow, Michael Moss, Moira Rankin and Lesley Richmond, 2001 Published by University of Glasgow, G12 8QQ Typeset by Media Services, University of Glasgow Printed by 21 Colour, Queenslie Industrial Estate, Glasgow, G33 4DB CIP Data for this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 0 85261 734 8 All rights reserved. Contents Introduction 7 A Brief History 9 The University of Glasgow 9 Predecessor Institutions 12 Anderson’s College of Medicine 12 Glasgow Dental Hospital and School 13 Glasgow Veterinary College 13 Queen Margaret College 14 Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama 15 St Andrew’s College of Education 16 St Mungo’s College of Medicine 16 Trinity College 17 The Constitution 19 The Papal Bull 19 The Coat of Arms 22 Management 25 Chancellor 25 Rector 26 Principal and Vice-Chancellor 29 Vice-Principals 31 Dean of Faculties 32 University Court 34 Senatus Academicus 35 Management Group 37 General Council 38 Students’ Representative Council 40 Faculties 43 Arts 43 Biomedical and Life Sciences 44 Computing Science, Mathematics and Statistics 45 Divinity 45 Education 46 Engineering 47 Law and Financial Studies 48 Medicine 49 Physical Sciences 51 Science (1893-2000) 51 Social Sciences 52 Veterinary Medicine 53 History and Constitution Administration 55 Archive Services 55 Bedellus 57 Chaplaincies 58 Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery 60 Library 66 Registry 69 Affiliated Institutions -

Recommended Public Holidays 2021

The Walled Garden, SJIB Circular 01/2021 Bush Estate Midlothian EH26 0SB 29 January 2021 Tel: 0131 445 9216 Fax: 0131 445 5548 www.sjib.org.uk To all SJIB and SELECT Members Dear Sir/Madam, LOCAL PUBLIC HOLIDAYS 2021 Please find attached a list of local Public Holiday dates for a number of towns and cities throughout Scotland for your information and records. Yours faithfully, Fiona Harper Pat Rafferty Alick Smith Secretary For UNITE the Union For SELECT Chairman: J. Simpson Director: A. Wilson LLM Secretary: F.M. Harper BA (Hons), MSc (Econ), FCIPD Established in 1969 by the constituent parties – SELECT and UNITE THE UNION Aberdeen City Council Spring Holiday 19 April * May Day 3 May * Trades Holiday 12 July * Autumn Holiday 27 September * Dumfries and Galloway Council Good Friday 2 April Easter Monday 5 April May Day 3 May Dundee City Council Easter Monday 5 April May Day 3 May Victoria Day 31 May Trades Holiday 26 July Autumn Holiday 4 October East Ayrshire Council Good Friday 2 April Easter Monday 5 April May Day 3 May September Weekend 17&20 September East Dunbartonshire Council Good Friday 2 April Easter Monday 5 April East Lothian Council Good Friday 2 April Easter Monday 5 April Autumn Holiday 17&20 September * East Renfrewshire Council Good Friday 2 April Easter Monday 5 April May Day 3 May * Spring Holiday 31 May * Autumn Holiday 24&27 September * City of Edinburgh Council Good Friday 2 April Easter Monday 5 April May Day 3 May Victoria Day 24 May Spring Holiday 31 May Autumn Holiday 30 September Falkirk Council Good Friday -

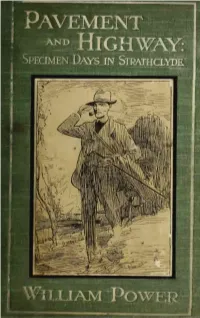

Pavement and Highway: Specimen Days in Strathclyde

Pavement *?S HIGHWAY: Specimen Days in Stimihclyde. ER Peter Orr—Copyright. GREY DAWN IN THE CITY. PAVEMENT AND HIGHWAY: SPECIMEN DAYS IN STRATHCLYDE. BY WILLIAM POWER. Glasgow: Archd. Sinclair. John Menzies & Co., Ltd., Glasgow and Edinburgh. 1911. TO F. HARCOURT KITCHIN. NOTE. Some part of the contents of this book has already appeared in substance in the Glasgow Herald, and is reproduced here by kind permission of the proprietors. The greater portion, however, is now published for the first time. My acknowledgments are also due to those who have given me permis- sion to reproduce the photographs which illustrate the text. As will probably be surmised, the first part of the book was irrevocably in type before the publication of Mr. Muirhead Bone's Glasgow Drawings. W. P. CONTENTS. PAGE. Picturesque Glasgow, ... l Glasgovia, 51 A Garden of Youth, 74 The City Walk, ------ 86 Ambitions, 98 Poet and Painter, 115 Above the Fog Line, 124 Back to the Land, 138 The Whangie, 144 The Loup of Fintry, 153 Mountain Corn, 162 Impressions of Galloway, - - - - 173 11 Doon the Watter," 183 A 1 ILLUSTRATIONS AND MAPS. Grey Dawn in the City - (Peter Orr) Frontispiece. St. Vincent Place - (A. R. Walker) Sketch Map of Giasgovia. At the Back o' Ballagioch (J. D. Cockburn) Mugdock Castle (Sir John Ure Primrose, Bart.) Gilmorehill, Evening (Peter Orr) Waterfoot, near Busby - (J. D. Cockburn) The Cart at Polnoon (J. D. Cockburn) Craigallian Loch and Dungoyne (A. R. Walker) Sketch Map of Firth of Clyde. PICTURESQUE GLASGOW. THE anthropomorphic habit of thought manifested in the polytheism of the Greeks and the mono- theism of the early Jews has been responsible, one supposes, for the familiar expression, "the body politic." But if the capital of a country be regarded as its head, there are few large states which have answered con- sistently to the anthropomorphic image. -

Sir Hector Hetherington and the Academicization of Glasgow Hospital Medicine Before the NHS

Medical History, 2001, 45: 207-242 Hector's House: Sir Hector Hetherington and the Academicization of Glasgow Hospital Medicine before the NHS ANDREW HULL* On 4 June 1945, Sir Alfred Webb-Johnson, the President of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, came to Glasgow to receive the Honorary Fellowship of the Royal Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons (RFPSG).' The Royal Faculty was an ancient medical licensing body whose office bearers and Fellows had traditionally made up the majority of the clinical elite in the two main local teaching hospitals.2 By the 1940s, however, the RFPSG was out of touch with the changing educational needs of the profession; both its local and national status were threatened by advances * Andrew John Hull, BA, MSc, PhD, Wellcome 'Alfred Edward Webb-Johnson, Baron Webb Unit for the History of Medicine, University of Johnson of Stoke-on-Trent (1880-1958), was Glasgow, 5 University Gardens, Glasgow G12 President of the Royal College of Surgeons, 8QQ. E-mail: ajh(arts.gla.ac.uk. 1941-9. See Dictionary of National Biography 1951-1960 (hereafter DNB), Oxford University This article was first given as a paper at the Third Press, 1971. Wellcome Trust Regional Forum in Glasgow on 11 2Founded in 1599, the Faculty of Physicians October 1997 when the author was a research and Surgeons of Glasgow (from 1909 Royal assistant on the Wellcome Trust funded project on Faculty and since 1962 Royal College) is one of the history ofthe Royal College of Physicians and the three ancient Scottish medical licensing bodies Surgeons of Glasgow. -

Matthew Mark Luke John

ACPN000702QK000.qxd 11/13/06 3:34 PM Page i Critical INTRODUCTION to the NEW TESTAMENT ACPN000702QK000.qxd 11/13/06 3:34 PM Page ii ACPN000702QK000.qxd 11/13/06 3:34 PM Page iii Critical INTRODUCTION to the NEW TESTAMENT Interpreting the Message and Meaning of Jesus Christ C ARL R. HOLLADAY Abingdon Press / Nashville ACPN000702QK000.qxd 11/13/06 3:34 PM Page iv A CRITICAL INTRODUCTION TO THE NEW TESTAMENT INTERPRETING THE MESSAGE AND MEANING OF JESUS CHRIST Copyright © 2005 by Abingdon Press All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, includ- ing photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission can be addressed to Abingdon Press, P.O. Box 801, 201 Eighth Avenue South, Nashville, TN 37202-0801, or e-mailed to [email protected]. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Holladay, Carl R. A critical introduction to the New Testament : interpreting the message and meaning of Jesus Christ / Carl R. Holladay. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-687-08569-1 (adhesive perfect binding : alk. paper) 1. Bible. N.T.—Criticism, interpretation, etc. I. Title. BS2361.3.H65 2005 225.6’1—dc22 2004030675 All scripture quotations unless noted otherwise are taken from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright 1989, by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America.