Archiving Movements Short Essays on Anime and Visual Media Materials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPA : Redesigning Animation

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. UPA : redesigning animation Bottini, Cinzia 2016 Bottini, C. (2016). UPA : redesigning animation. Doctoral thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/69065 https://doi.org/10.32657/10356/69065 Downloaded on 05 Oct 2021 20:18:45 SGT UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI SCHOOL OF ART, DESIGN AND MEDIA 2016 UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI School of Art, Design and Media A thesis submitted to the Nanyang Technological University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.” Paul Klee, “Creative Credo” Acknowledgments When I started my doctoral studies, I could never have imagined what a formative learning experience it would be, both professionally and personally. I owe many people a debt of gratitude for all their help throughout this long journey. I deeply thank my supervisor, Professor Heitor Capuzzo; my cosupervisor, Giannalberto Bendazzi; and Professor Vibeke Sorensen, chair of the School of Art, Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore for showing sincere compassion and offering unwavering moral support during a personally difficult stage of this Ph.D. I am also grateful for all their suggestions, critiques and observations that guided me in this research project, as well as their dedication and patience. My gratitude goes to Tee Bosustow, who graciously -

Motion Enriching Using Humanoide Captured Motions

MASTER THESIS: MOTION ENRICHING USING HUMANOIDE CAPTURED MOTIONS STUDENT: SINAN MUTLU ADVISOR : A NTONIO SUSÌN SÀNCHEZ SEPTEMBER, 8TH 2010 COURSE: MASTER IN COMPUTING LSI DEPERTMANT POLYTECNIC UNIVERSITY OF CATALUNYA 1 Abstract Animated humanoid characters are a delight to watch. Nowadays they are extensively used in simulators. In military applications animated characters are used for training soldiers, in medical they are used for studying to detect the problems in the joints of a patient, moreover they can be used for instructing people for an event(such as weather forecasts or giving a lecture in virtual environment). In addition to these environments computer games and 3D animation movies are taking the benefit of animated characters to be more realistic. For all of these mediums motion capture data has a great impact because of its speed and robustness and the ability to capture various motions. Motion capture method can be reused to blend various motion styles. Furthermore we can generate more motions from a single motion data by processing each joint data individually if a motion is cyclic. If the motion is cyclic it is highly probable that each joint is defined by combinations of different signals. On the other hand, irrespective of method selected, creating animation by hand is a time consuming and costly process for people who are working in the art side. For these reasons we can use the databases which are open to everyone such as Computer Graphics Laboratory of Carnegie Mellon University. Creating a new motion from scratch by hand by using some spatial tools (such as 3DS Max, Maya, Natural Motion Endorphin or Blender) or by reusing motion captured data has some difficulties. -

The Anime Galaxy Japanese Animation As New Media

i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i Herlander Elias The Anime Galaxy Japanese Animation As New Media LabCom Books 2012 i i i i i i i i Livros LabCom www.livroslabcom.ubi.pt Série: Estudos em Comunicação Direcção: António Fidalgo Design da Capa: Herlander Elias Paginação: Filomena Matos Covilhã, UBI, LabCom, Livros LabCom 2012 ISBN: 978-989-654-090-6 Título: The Anime Galaxy Autor: Herlander Elias Ano: 2012 i i i i i i i i Índice ABSTRACT & KEYWORDS3 INTRODUCTION5 Objectives............................... 15 Research Methodologies....................... 17 Materials............................... 18 Most Relevant Artworks....................... 19 Research Hypothesis......................... 26 Expected Results........................... 26 Theoretical Background........................ 27 Authors and Concepts...................... 27 Topics.............................. 39 Common Approaches...................... 41 1 FROM LITERARY TO CINEMATIC 45 1.1 MANGA COMICS....................... 52 1.1.1 Origin.......................... 52 1.1.2 Visual Style....................... 57 1.1.3 The Manga Reader................... 61 1.2 ANIME FILM.......................... 65 1.2.1 The History of Anime................. 65 1.2.2 Technique and Aesthetic................ 69 1.2.3 Anime Viewers..................... 75 1.3 DIGITAL MANGA....................... 82 1.3.1 Participation, Subjectivity And Transport....... 82 i i i i i i i i i 1.3.2 Digital Graphic Novel: The Manga And Anime Con- vergence........................ 86 1.4 ANIME VIDEOGAMES.................... 90 1.4.1 Prolongament...................... 90 1.4.2 An Audience of Control................ 104 1.4.3 The Videogame-Film Symbiosis............ 106 1.5 COMMERCIALS AND VIDEOCLIPS............ 111 1.5.1 Advertisements Reconfigured............. 111 1.5.2 Anime Music Video And MTV Asia......... -

Marco Balzarotti

MARCO BALZAROTTI (Curriculum Professionale liberamente fornito dall'utente a Voci.FM) link originale (thanks to): http://www.antoniogenna.net/doppiaggio/voci/vocimbal.htm Alcuni attori e personaggi doppiati: FILM CINEMA Spencer Garrett in "Il nome del mio assassino" (Ag. Phil Lazarus), "Il cammino per Santiago" (Phil) Viggo Mortensen in "American Yakuza" (Nick Davis / David Brandt) Michael Wisdom in "Masked and Anonymous" (Lucius) John Hawkes in "La banda del porno - Dilettanti allo sbaraglio!" (Moe) Jake Busey in "The Hitcher II - Ti stavo aspettando" (Jim) Vinnie Jones in "Brivido biondo" (Lou Harris) Larry McHale in "Joaquin Phoenix - Io sono qui!" (Larry McHale) Paul Sadot in "Dead Man's Shoes - Cinque giorni di vendetta" (Tuff) Jerome Ehlers in "Presa mortale" (Van Buren) John Surman in "I'll Sleep When I'm Dead" (Anatomopatologo) Anthony Andrews in "Attacco nel deserto" (Magg. Meinertzhagen) William Bumiller in "OP Center" (Lou Bender) Miles O'Keefe in "Liberty & Bash" (Liberty) Colin Stinton in "The Commander" (Ambasc. George Norland) Norm McDonald in "Screwed" Jeroen Krabbé in "The Punisher - Il Vendicatore" (1989) (Gianni Franco, ridopp. TV) Malcolm Scott in "Air Bud vince ancora" (Gordon) Robert Lee Oliver in "Oh, mio Dio! Mia madre è cannibale" (Jeffrey Nathan) John Corbett in "Prancer - Una renna per amico" (Tom Sullivan) Paul Schrier in "Power Rangers: Il film" e "Turbo - A Power Rangers Movie" (Bulk) Samuel Le Bihan in "Frontiers - Ai confini dell'inferno" (Goetz) Stefan Jürgens in "Porky college 2 - Sempre più duro!" (Padre di Ryan) Tokuma Nishioka in "Godzilla contro King Ghidora" (Prof. Takehito Fujio) Kunihiko Mitamura in "Godzilla contro Biollante" (Kazuhito Kirishima) Choi Won-seok in "La leggenda del lago maledetto" (Maestro Myo-hyeon) Eugene Nomura in "Gengis Khan - Il grande conquistatore" (Borchu) FILM D'ANIMAZIONE (CINEMA E HOME-VIDEO) . -

Animation: Types

Animation: Animation is a dynamic medium in which images or objects are manipulated to appear as moving images. In traditional animation, images are drawn or painted by hand on transparent celluloid sheets to be photographed and exhibited on film. Today most animations are made with computer generated (CGI). Commonly the effect of animation is achieved by a rapid succession of sequential images that minimally differ from each other. Apart from short films, feature films, animated gifs and other media dedicated to the display moving images, animation is also heavily used for video games, motion graphics and special effects. The history of animation started long before the development of cinematography. Humans have probably attempted to depict motion as far back as the Paleolithic period. Shadow play and the magic lantern offered popular shows with moving images as the result of manipulation by hand and/or some minor mechanics Computer animation has become popular since toy story (1995), the first feature-length animated film completely made using this technique. Types: Traditional animation (also called cel animation or hand-drawn animation) was the process used for most animated films of the 20th century. The individual frames of a traditionally animated film are photographs of drawings, first drawn on paper. To create the illusion of movement, each drawing differs slightly from the one before it. The animators' drawings are traced or photocopied onto transparent acetate sheets called cels which are filled in with paints in assigned colors or tones on the side opposite the line drawings. The completed character cels are photographed one-by-one against a painted background by rostrum camera onto motion picture film. -

Computerising 2D Animation and the Cleanup Power of Snakes

Computerising 2D Animation and the Cleanup Power of Snakes. Fionnuala Johnson Submitted for the degree of Master of Science University of Glasgow, The Department of Computing Science. January 1998 ProQuest Number: 13818622 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818622 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 GLASGOW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY U3 ^coji^ \ Abstract Traditional 2D animation remains largely a hand drawn process. Computer-assisted animation systems do exists. Unfortunately the overheads these systems incur have prevented them from being introduced into the traditional studio. One such prob lem area involves the transferral of the animator’s line drawings into the computer system. The systems, which are presently available, require the images to be over- cleaned prior to scanning. The resulting raster images are of unacceptable quality. Therefore the question this thesis examines is; given a sketchy raster image is it possible to extract a cleaned-up vector image? Current solutions fail to extract the true line from the sketch because they possess no knowledge of the problem area. -

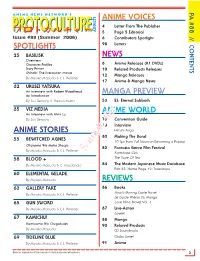

Protoculture Addicts

PA #88 // CONTENTS PA A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S ANIME VOICES 4 Letter From The Publisher PROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]-PROTOCULTURE ADDICTS 5 Page 5 Editorial Issue #88 (Summer 2006) 6 Contributors Spotlight SPOTLIGHTS 98 Letters 25 BASILISK NEWS Overview Character Profiles 8 Anime Releases (R1 DVDs) Story Primer 10 Related Products Releases Shinobi: The live-action movie 12 Manga Releases By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 17 Anime & Manga News 32 URUSEI YATSURA An interview with Robert Woodhead MANGA PREVIEW An Introduction By Zac Bertschy & Therron Martin 53 ES: Eternal Sabbath 35 VIZ MEDIA ANIME WORLD An interview with Alvin Lu By Zac Bertschy 73 Convention Guide 78 Interview ANIME STORIES Hitoshi Ariga 80 Making The Band 55 BEWITCHED AGNES 10 Tips from Full Moon on Becoming a Popstar Okusama Wa Maho Shoujo 82 Fantasia Genre Film Festival By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Sample fileKamikaze Girls 58 BLOOD + The Taste Of Tea By Miyako Matsuda & C. Macdonald 84 The Modern Japanese Music Database Part 35: Home Page 19: Triceratops 60 ELEMENTAL GELADE By Miyako Matsuda REVIEWS 63 GALLERY FAKE 86 Books Howl’s Moving Castle Novel By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Le Guide Phénix Du Manga 65 GUN SWORD Love Hina, Novel Vol. 1 By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 87 Live-Action Lorelei 67 KAMICHU! 88 Manga Kamisama Wa Chugakusei 90 Related Products By Miyako Matsuda CD Soundtracks 69 TIDELINE BLUE Otaku Unite! By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 91 Anime More on: www.protoculture-mag.com & www.animenewsnetwork.com 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ LETTER FROM THE PUBLISHER A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S PROTOCULTUREPROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]- ADDICTS Over seven years of writing and editing anime reviews, I’ve put a lot of thought into what a Issue #88 (Summer 2006) review should be and should do, as well as what is shouldn’t be and shouldn’t do. -

The University of Chicago Looking at Cartoons

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LOOKING AT CARTOONS: THE ART, LABOR, AND TECHNOLOGY OF AMERICAN CEL ANIMATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CINEMA AND MEDIA STUDIES BY HANNAH MAITLAND FRANK CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2016 FOR MY FAMILY IN MEMORY OF MY FATHER Apparently he had examined them patiently picture by picture and imagined that they would be screened in the same way, failing at that time to grasp the principle of the cinematograph. —Flann O’Brien CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES...............................................................................................................................v ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................................vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS....................................................................................................................viii INTRODUCTION LOOKING AT LABOR......................................................................................1 CHAPTER 1 ANIMATION AND MONTAGE; or, Photographic Records of Documents...................................................22 CHAPTER 2 A VIEW OF THE WORLD Toward a Photographic Theory of Cel Animation ...................................72 CHAPTER 3 PARS PRO TOTO Character Animation and the Work of the Anonymous Artist................121 CHAPTER 4 THE MULTIPLICATION OF TRACES Xerographic Reproduction and One Hundred and One Dalmatians.......174 -

Cel Animation and Define the Words That

Chapter 5-Animation Objective The students will be able to: define animation and describe how it can be used in multimedia. discuss the origins of cel animation and define the words that originate from this technique. define the capabilities of computer animation and the mathematical techniques that differ from traditional cel animation. discuss some of the general principles and factors that apply to the creation of computer animation for multimedia presentations. Overview Introduction to animation. Computer-generated animation. File formats used in animation. Making successful animations. Introduction to Animation Animation is defined as the act of making something come alive. It is concerned with the visual or aesthetic aspect of the project. Animation is an object moving across or into or out of the screen. Introduction to Animation Animation is possible because of a biological phenomenon known as persistence of vision and a psychological phenomenon called phi. In animation, a series of images are rapidly changed to create an illusion of movement. Usage of Animation Artistic purposes Storytelling Displaying data (scientific visualization) Instructional purposes 12 Basic Principles of Animation 1. Timing The basics are: more drawings between poses slow and smooth the action. Fewer drawings make the action faster and crisper. A variety of slow and fast timing within a scene adds texture and interest to the movement. 12 Basic Principles of Animation 2. Secondary Action This action adds to and enriches the main action and adds more dimension to the character animation, supplementing and/or re-enforcing the main action. 12 Basic Principles of Animation 3. Follow Through and Overlapping Action When the main body of the character stops, all other parts will continue to catch up to the main mass of the character, such as arms, long hair, clothing, coat tails or a dress, floppy ears or a long tail (these follow the path of action). -

Piracy Or Productivity: Unlawful Practices in Anime Fansubbing

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aaltodoc Publication Archive Aalto-yliopisto Teknillinen korkeakoulu Informaatio- ja luonnontieteiden tiedekunta Tietotekniikan tutkinto-/koulutusohjelma Teemu Mäntylä Piracy or productivity: unlawful practices in anime fansubbing Diplomityö Espoo 3. kesäkuuta 2010 Valvoja: Professori Tapio Takala Ohjaaja: - 2 Abstract Piracy or productivity: unlawful practices in anime fansubbing Over a short period of time, Japanese animation or anime has grown explosively in popularity worldwide. In the United States this growth has been based on copyright infringement, where fans have subtitled anime series and released them as fansubs. In the absence of official releases fansubs have created the current popularity of anime, which companies can now benefit from. From the beginning the companies have tolerated and even encouraged the fan activity, partly because the fans have followed their own rules, intended to stop the distribution of fansubs after official licensing. The work explores the history and current situation of fansubs, and seeks to explain how these practices adopted by fans have arisen, why both fans and companies accept them and act according to them, and whether the situation is sustainable. Keywords: Japanese animation, anime, fansub, copyright, piracy Tiivistelmä Piratismia vai tuottavuutta: laittomat toimintatavat animen fanikäännöksissä Japanilaisen animaation eli animen suosio maailmalla on lyhyessä ajassa kasvanut räjähdysmäisesti. Tämä kasvu on Yhdysvalloissa perustunut tekijänoikeuksien rikkomiseen, missä fanit ovat tekstittäneet animesarjoja itse ja julkaisseet ne fanikäännöksinä. Virallisten julkaisujen puutteessa fanikäännökset ovat luoneet animen nykyisen suosion, jota yhtiöt voivat nyt hyödyntää. Yhtiöt ovat alusta asti sietäneet ja jopa kannustaneet fanien toimia, osaksi koska fanit ovat noudattaneet omia sääntöjään, joiden on tarkoitus estää fanikäännösten levitys virallisen lisensoinnin jälkeen. -

Re-Imagining Animation the Changing Face of The

RiA cover UK AW.qxd 6/3/08 10:40 AM Page 1 – – – – – – Chapter 05 Chapter 04 Chapter 03 Chapter 02 Chapter 01 The disciplinary shift Approaches and outlooks The bigger picture Paul Wells / Johnny Hardstaff Paul Wells Re-imagining Animation RE-IMAGINING RE-IMAGINING ANIMATION ANIMATION – The Changing Face of the Moving Image The Changing Face Professor Paul Wells is Director of the Re-imagining Animation is a vivid, insightful Re-imagining Animation Other titles of interest in AVA's Animation Academy at Loughborough and challenging interrogation of the animated addresses animation’s role at the heart THE CHANGING THEAcademia CHANG range include: University, UK, and has published widely film as it becomes central to moving image of moving-image practice through an in the field of animation, including practices in the contemporary era. engagement with a range of moving-image Visible Signs: The Fundamentals of Animation and Animation was once works – looking at the context in which FACE OF THE FACEAn introduction OF to semiotics THE Basics Animation: Scriptwriting. constructed frame-by-frame, one image they were produced; the approach to their following another in the process of preparation and construction; the process of Visual Research: Johnny Hardstaff is an internationally constructing imagined phases of motion, their making; the critical agenda related to MOVING IMAGE MOVINGAn introduction to research IM established, award-winning designer, film- but now the creation and manipulation the research; developmental and applied methodologies in graphic design maker and artist. He is the creator of The of the moving image has changed. aspects of the work; the moving-image History of Gaming and The Future of With the digital revolution outcomes; and the status of the work within Visual Communication: Gaming, and innovative popular music videos, invading every creative enterprise and form contemporary art and design practices. -

The Uses of Animation 1

The Uses of Animation 1 1 The Uses of Animation ANIMATION Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of the rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon. Animators are artists who specialize in the creation of animation. Animation can be recorded with either analogue media, a flip book, motion picture film, video tape,digital media, including formats with animated GIF, Flash animation and digital video. To display animation, a digital camera, computer, or projector are used along with new technologies that are produced. Animation creation methods include the traditional animation creation method and those involving stop motion animation of two and three-dimensional objects, paper cutouts, puppets and clay figures. Images are displayed in a rapid succession, usually 24, 25, 30, or 60 frames per second. THE MOST COMMON USES OF ANIMATION Cartoons The most common use of animation, and perhaps the origin of it, is cartoons. Cartoons appear all the time on television and the cinema and can be used for entertainment, advertising, 2 Aspects of Animation: Steps to Learn Animated Cartoons presentations and many more applications that are only limited by the imagination of the designer. The most important factor about making cartoons on a computer is reusability and flexibility. The system that will actually do the animation needs to be such that all the actions that are going to be performed can be repeated easily, without much fuss from the side of the animator.