BMH.WS0971.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irish Language Court Interpreting 1801-1922

Irish Language Court Interpreting 1801-1922 Mary Phelan Thesis submitted for the qualification of PhD Supervisor: Dr. Dorothy Kenny School of Applied Language and Intercultural Studies Dublin City University 2013 Declaration I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of PhD is entirely my own work, and that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copyright, and has not been taken from the work others save to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed ID No. 58106154 Date: 21st January 2013 i Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to Dr Dorothy Kenny for her supportive supervision, excellent suggestions and incisive feedback. Thanks are also due to my previous supervisor Professor Jenny Williams from whom I learnt a lot. This research would not have been possible without the help of a number of people. I would like to thank Professor Emeritus Leo Hickey for inadvertently sowing the seed for this study; Dr Aidan Kane, NUI Galway, for telling me about the House of Commons Parliamentary Papers database; Siobhán Dunne, DCU Library, for promptly organising access to that database; Gregory O’Connor, National Archives of Ireland, for sharing his in-depth knowledge of registered papers, country letter books and grand jury presentment books; staff at the National Archives of Ireland, National Library of Ireland and Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI). -

Paseta Text.Indd

The Kehoe Lecture in Irish History 2018 Suffrage and citizenship in Ireland, 1912–18 Senia Pašeta LONDON INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Published by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU 2019 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN 978-1-912702-18-3 (PDF edition) ISBN 978-1-912702-31-2 (paperback edition) DOI 10.14296/119.9781912702183 Senia Pašeta is professor of modern history at the University of Oxford and a fellow of St Hugh’s College, Oxford. A specialist in the history of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Ireland, Senia’s current research focuses on women’s political activism and on connections between Irish and British radical politics. Her publications include Irish Nationalist Women, 1900–1918 (Cambridge, 2013) and Uncertain Futures: Essays about the Irish Past (Oxford, 2016). The Kehoe Lecture in Irish Historyis one of the principal named lectures hosted each year by the Institute of Historical Research, University of London. Inaugurated in 2016, the Kehoe Lecture promotes new research undertaken by leading scholars of Irish history and culture. Suffrage and citizenship in Ireland, 1912–18 Senia Pašeta Presented on 15 November 2018 at the Institute of Historical Research, University of London All Irish historians and anyone interested in Irish history will know that we have for some time been in the middle of a decade of centenaries. -

Recollections of Dublin Castle Q

Rec olle c tio n s of ’ Dubli n Castle Q o f Dublin Society Recollections of Dublin Castle 9 @ of Dublin Society O F old D — dear, , and dirty ublin Lady Mor ’ - — gan s well known descriptio n I was a denizen So am for forty years and more . I well s versed in all its ways , humour , delusions , and amiable deceits , and might claim to know — it by heart . Dear it was old , certainly and b dilapidated eyond dispute . As to the dirt , it was unimpeachable . No native , however , was known to admit any of these blemishes . It is a pleasant and rather original old oo d find city, where people of g spirits will ' ofi erin plenty to entertain them , but g one enjoyable characteristic in the general spirit “ ” of make-believe (humbug is too coarse a term) which prevails everywhere . The natives I A 206109 8 Recollections of Dublin Castle will maintain against all comers that it is the “ fi nest city going , and that its society is second ” to none , sir . Among themselves even there is a good-natured sort of conspiracy to keep up ” fi ction the , always making believe , as much as the Little Marchioness herself. Where , a my boy, would you see such be utiful faces or ’ ' — ’ — ’ th I rish eyes don t tell me and where ud ’ ’ (this u d is a favourite abbrevi ation) u d find ih you hear such music , or such social tercourse divarshions I , or such general , was all i like the rest , beguiled by th s and i all was l bel eved in it , and it not unti years after I had left that the glamour dissolved . -

List of Officers and Men Serving in the First Canadian Contingent of The

7* LIST OF OFFICERS AND MEN Serving in the FIRST Canadian Contingent of the British Expeditionary Force, 1914. : COMPILED BY PAY AND RECORD OFFICE, CANADIAN CONTINGENT, 36, VICTORIA STREET, LONDON, S.W. D 54? INDEX. PAGES. HEADQUARTERS, FIRST CANADIAN CONTINGENT 5, 6 DIVISIONAL HEADQUARTERS SUBORDINATE STAF?... ... ... 6-8 FIRST INFANTRY BRIGADE HEADQUARTERS ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 8 IST BATTALION 9-21 2ND BATTALION 21-34 SRD BATTALION ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 34-47 4TH BATTALION 47-60 SECOND INFANTRY BRIGADE HEADQUARTERS 60,61 STH BATTALION 61-74 6TH BATTALION 75-87 ?TH BATTALION 88-101 STH BATTALION 101-114 THIRD INFANTRY BRIGADE HEADQUARTERS 114 13ra BATTALION 115-128 - 14TH BATTALION ... 128-141 15TH BATTALION 141-153 16iH BATTALION 154-167 FOURTH INFANTRY BRIGADE STAFF, &c. 167 BATTALION ".., 168-180 y9ra V 10TH BATTALION .... .,; 181-192 HTH BATTALION ...'. 192-206 12iH BATTALION 206-217 17iH BATTALION (NOT BRIGADED) 217-227 PRINCESS PATRICIA'S CANADIAN LIGHT INFANTRY ... ... 227-238 DIVISIONAL SIGNAL COMPANY 238-240 DIVISIONAL CAVALRY 241,242 DIVISIONAL CYCLIST COMPANY ... : i,.. ... 243 ROYAL CANADIAN DRAGOONS 244-250 LORD STRATHCONA'S HORSE (R.C.) ... ....**.. 251-257 DIVISIONAL ARTILLERY HEADQUARTERS 258 FIRST ARTILLERY BRIGADE AND AMMUNITION COLUMN 258-267 3 A2 SECOND CANADIAN FIELD ARTILLERY BRIGADE PAGES. BRIGADE STAFF 267,268 4iH BATTERY 268-270 STH BATTERY 270-272 6TH BATTERY 272-274 AMMUNITION COLUMN 274-276 THIRD CANADIAN FIELD ARTILLERY BRIGADE BRIGADE STAFF 277 7TH BATTERY 277-279 STH BATTERY 280,281 9ra BATTERY 282-284 AMMUNITION COLUMN 285,286 No. 1 HEAVY BATTERY 286-288 ROYAL CANADIAN HORSE ARTILLERY 289-294 DIVISIONAL ENGINEERS 294-302 DIVISIONAL TRAIN 303-308 DIVISIONAL SUPPLY COLUMN, M.T 308-311 DIVISIONAL AMMUNITION COLUMN , 311-318 DIVISIONAL AMMUNITION PARK, WITH C.F.A. -

Author's and Readers' Updates to "Up to Rawdon"

Updates - UP TO RAWDON, © by Daniel B. Parkinson Page 1 of 100 , revised October 2, 2019 UP TO RAWDON was published in paperback and PDF formats, on February 16, 2013. See www.uptorawdon.com/#order. This document Author’s and Readers’ Updates (www.uptorawdon.com/updates) contains revised text, comments and contacts for readers interested in particular families. It is updated periodically. Associated photographs are found at www.uptorawdon.com/updates-photo Page Family Details i Cover: Johnston Cabin (Tenth Range, Lot 24 South) by the late Linda Blagrave, photographed by Richard Prud’homme, of Rawdon. Ken McRory, Guelph, Ontario designer. Part One correction: ISBN 978-0-9917126-0-1 (paper) ii correction: ISBN 978-0-9917126-2-5 (e-book) Part One, map correction: The title should say RAWDON TOWNSHIP IN 1820; the caption makes it clear the map was page iv originally drawn in 1805. This map image is found in Part One and Part Two. and Part Two. How a copy of the map was used by William Holtby when Township Secretary Treasurer is described in Part page iv One, page xviii, paragraph four. Photo www.uptorawdon.com/photop372 of Michael E. Holtby of Denver, Colorado holding his 3X great grandfather’s copy of the map and which Michael has given to me. This 1840 and later Rawdon Township map is accessible to all at http://uptorawdon.com/research.html. Page xiii Colclough Background on the crown agent Guy Carleton Colclough and his father Major Beauchamp Colclough and their P’gph. 2 connection to the former Governor of Quebec: http://uptorawdon.com/41-Beauchamp-Colclough.pdf Page xviii Holtby Michael Holtby is a 3X great grandson of William Holtby P’gph. -

United Irish League, and M.P

From: Redmond Enterprise Ronnie Redmond To: FOMC-Regs-Comments Subject: Emailing redmond.pdf Date: Wednesday, October 14, 2020 2:44:55 PM Attachments: redmond.pdf NONCONFIDENTIAL // EXTERNAL I want this cause im a Redmond and i want to purchase all undeveloped and the government buildings the Queen of England even if i have to use PROBATES LAW RONNIE JAMES REDMOND Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 118 PAPERS OF JOHN REDMOND MSS 3,667; 9,025-9,033; 15,164-15,280; 15,519-15,521; 15,523-15,524; 22,183- 22,189; 18,290-18,292 (Accessions 1154 and 2897) A collection of the correspondence and political papers of John Redmond (1856-1918). Compiled by Dr Brian Kirby holder of the Studentship in Irish History provided by the National Library of Ireland in association with the National Committee for History. 2005-2006. The Redmond Papers:...........................................................................................5 I Introduction..........................................................................................................5 I.i Scope and content: .....................................................................................................................5 I.ii Biographical history: .................................................................................................................5 I.iii Provenance and extent: .........................................................................................................7 I.iv Arrangement and structure: ..................................................................................................8 -

Paseta 21Jan.Indd

Downloaded from the Humanities Digital Library http://www.humanities-digital-library.org Open Access books made available by the School of Advanced Study, University of London ***** Publication details: Suffrage and citizenship in Ireland, 1912–18 Senia Pašeta http://humanities-digital-library.org/index.php/hdl/catalog/book/paseta DOI: 10.14296/119.9781912702183 ***** This edition published 2019 by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU, United Kingdom ISBN 978-1-912702-18-3 This work is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses Suff rage and citizenship in Ireland, 1912–18 The Kehoe Lecture in Irish History 2018 Senia Pašeta IHR SHORTS The Kehoe Lecture in Irish History 2018 Suffrage and citizenship in Ireland, 1912–18 Senia Pašeta LONDON INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Published by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU 2019 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN 978-1-912702-18-3 DOI 10.14296/119.9781912702183 Senia Pašeta is professor of modern history at the University of Oxford and a fellow of St Hugh’s College, Oxford. A specialist in the history of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Ireland, Senia’s current research focuses on women’s political activism and on connections between Irish and British radical politics. -

Bbm:978-1-349-18546-7/1.Pdf

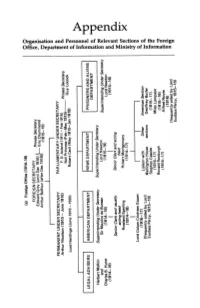

(a) Foreign Office (1914-18) 00 FOREIGN SECRETARY Private Secretary Edward Grey (until Dec 1916) }-Eric Drummond ..~i ... Arthur Balfour (after Dec 1916) (1915-19) oil tD a. I "tS 0 I l ~ =:s PERMANENT UNDER SECRETARY PARLIAMENTARY UNDER SECRETARY Arthur Nicolson (1910- June 1916) F. D. Acland (1911- Feb 1915) Private Secretary i=tD c. Neil Primrose (Feb-May 1915)-- Cecil (May 1915-Jan 1919) Guy Locock a~ Lord Hardinge (June 1916 -1920) Robert 0 tD ....-o ;! I I I I S.s > LEGAL ADVISERS 'AMERICAN DEPARTMENT' 'NEWS DEPARTMENT' PRISONERS AND ALIENS t!. ~ I I DEPARTMENT a ~ a. ~ Herbert Malkin Superintending Under Secretary Superintending Under Secretary Newton g.:= and Sir Maurice de BUnsen Lord Superintending Under Secretary tD (1915-16) =:s ro Charles B. Hurst (1914-18) Lord Newton ~ -tD (1914-18) I I (1915-16) =:s < ~ Senior Clerk and usually Senior Clerk and acting c.= a:: ... 0.. acting head head ... Cll ,.... Sperling Hubert Montgomery Rowland ...=:s I')tD (1914-18) (1914-17) X I I ---~ ~§ Lord Colum Crichton Stuart I 0 fll (1916-17) Liaison with Other American Section .... 0 (frequently aided by Lord Wellington House sections Geoffrey Butler =:f .... Eustace Percy, 1915-16) Stephen Gaselee (1915-17) a'Ef (1916-171 Miles Lampson ... tD Ronald Roxburgh (1915-16) 2 :r (1916-17) Alfred Noyes a.; (1916) 0 ... (frequently aided by Lord =:s~ Eustace Percy, 1915-16) (b) Department of Information (Feb 1917-Jan 1918) SUPERINTENDING CABINET MINISTER Lloyd George (Feb-Sep 1917) Edward Carson (Sep 1917-Jan 1918) I DIRECTOR John Buchan-Private Secretary: 1 Stair Gillion I l I l AND LIBRARY [INTELLIGENCE STAF~ ADMINISTRATION-ALLIED I~RT I ~u~~;-~~TAFFJ AND NEUTRAL PROPAGANDA Assistant Director Financial Assistant Director Deputy Director Charles Masterman Comptroller Major-General Lord Hubert Montgomery ~-·--I Edward Gleichen I -, I -1 Books Distribution Pictorial Art t~- Pamphlets Publications ATFO ABROAD Newspapers Exhibitions USA USA Ronald Roxburgh Geoffrey Butler Far East and Moslem H. -

Fifteenth Battalion

(ISSUED WITH MILITIA ORDERS, 1915.) CANADIAN EXPEDITIONARY FORCE FIFTEENTH BATTALION NOMINAL ROLL OF OFFICERS, NON -COMMISSIONED OFFICERS AND MEN. OTTAWA GOVERNMENT PRINTING BUREAU 75501-1 1915 15th BATTALION. t :, Reg. Country TAKEN ON STRENGTH No. Rank. Name, Surname First. Corps (if any). Naine of Next of Kin. Address of Next of Kin. of Birth. Place. Date. i I I 1914. Lieut. -Col Currie, John Allister 48th W Regt.... Currie, Helen 33 Howland Ave., Toronto, Ont Canada ! Valcartier.. Sept. 22 Major Marshall, William Renwick C. M. R Marshall, Elizabeth (Mrs.).... 575 Huron St., Toronto, Ont Canada Captain Valcartier.. Sept. 22 Darling, Robert Clifford R. M. C Darling, Phyllis Alleyne 1106 C.P.R. Bldg., Toronto, Ont Canada I Valcartier.. Sept. 22 Captain Warren, Trumbell R. M. C Warren, Marjory Laura (Mrs.) 47 Yonge St., Toronto, Ont England Valcartier.. Sept. 20 Captain Donaldson, Robert L. M 43rd Regt Donaldson, J. B. (Lt.-Cor.) . 197 McKay St., Ottawa, Ont !Canada Valcartier.. Sept. 23 Hon. Captain... Mabee, Oliver Hugel 48th Regt Mabee, C. P Fort Erie, Ont (Canada Valcartier.. Sept. 22 Lieutenant Lawson, Walter B 48th Regt Lawson, J. L Barrie, Ont Canada Valcartier.. Sept. 23 Supr. Lieut Long, firnest J 1st Hus Long, J. C Beamsville, Ont Canada Valcartier..! Sept. 20 Lieutenant McKessock, Robert Russell... 97th Regt McKessock, Caroline Box 302, Sudbury, Ont d Canada .. Valcartier.. Sept. 20 Major MacKenzie, Alexander J 148th Regt MacKenzie, P. H Lucknow, Ont Canada Valcartier.. (Sept. 22 cs "A" COMPANY. Captain McGregor, Archibald R 48th Regt McGregor, Duncan Martintown, Glengarry, Ont Canada Valcartier.. Sept. 22 Lieutenant Davidson, Robert Hay '48th Regt Davidson, Mrs 18 Madison Ave., Toronto, Ont Canada Valcartier. -

A Decade of Change: Donegal and Ireland 1912 - 1923

DONEGAL COUNTY ARCHIVES CARTLANN CHONTAE DHÚN NA NGALL A DECADE OF CHANGE: DONEGAL AND IRELAND 1912 - 1923 DOCUMENT STUDY PACK design: onthedotmultimedia.com 087 9130155 Contents PART ONE: CONTEXT Overview of Ireland, 1870 - 1912 3 Introduction 3 Diversity in Nineteenth Century Ireland 4 Land Reform, Home Rule and the Land War 5 Rise of Unionism 7 Cultural Nationalism 8 Donegal in 1912 9 PART TWO: 1912 – 1923 The Third Home Rule Bill 10 Resistance to Home Rule 12 World War One 15 The 1916 Rising 18 The General Election of 1918 20 The War of Independence 22 Truce and the Anglo-Irish Treaty 26 The Civil War 28 Aftermath and Legacy 31 PART THREE: BIOGRAPHIES The National Leaders 34 The Local Leaders 37 PART FOUR: DEALING WITH DOCUMENTS 40 References 42 Additional Reading 42 Acknowledgements 44 1 PART ONE CONTEXT PART ONE: CONTEXT Overview of Ireland tensions, while the establishment of different forms of Christian religions during the Reformation and 1870 – 1912 the attempts to impose the Reformation on Ireland had added religious tensions. In addition, attempts INTRODUCTION by the Irish population to regain control of the land and the country had led to rebellion and counter- The period 1912 – 1923 is perhaps one of the most rebellion. The 1798 rebellion was the first and important in Irish history. The events that occurred only time that people from all religious creeds in during this decade transformed the island of Ireland Ireland united in pursuit of a common goal – liberty and have had a lasting legacy on Irish politics and and equality for Ireland through freedom from Britain. -

1918 Diary of Sir Horace Curzon Plunkett (1854–1932) Transcribed, Annotated and Indexed by Kate Targett

1918 Diary of Sir Horace Curzon Plunkett (1854–1932) Transcribed, annotated and indexed by Kate Targett. December 2012 NOTES ‘There was nothing wrong with my head, but only with my handwriting, which has often caused difficulties.’ Horace Plunkett, Irish Homestead, 30 July 1910 Conventions In order to reflect the manuscript as completely and accurately as possible and to retain its original ‘flavour’, Plunkett’s spelling, punctuation, capitalisation and amendments have been reproduced unless otherwise indicated. The conventions adopted for transcription are outlined below. 1) Common titles (usually with an underscored superscript in the original) have been standardised with full stops: Archbp. (Archbishop), Bp. (Bishop), Capt./Capt’n., Col., Fr. (Father), Gen./Gen’l , Gov./Gov’r (Governor), Hon. (Honourable), Jr., Ld., Mr., Mrs., Mgr. (Monsignor), Dr., Prof./Prof’r., Rev’d. 2) Unclear words for which there is a ‘best guess’ are preceded by a query (e.g. ?battle) in transcription; alternative transcriptions are expressed as ?bond/band. 3) Illegible letters are represented, as nearly as possible, by hyphens (e.g. b----t) 4) Any query (?) that does not immediately precede a word appears in the original manuscript unless otherwise indicated. 5) Punctuation (or lack of) Commas have been inserted only to reduce ambiguity. ‘Best guess’ additions appear as [,]. Apostrophes have been inserted in: – surnames beginning with O (e.g. O’Hara) – negative contractions (e.g. can’t, don’t, won’t, didn’t) – possessives, to clarify context (e.g. Adams’ house; Adam’s house). However, Plunkett commonly indicates the plural of surnames ending in ‘s’ by an apostrophe (e.g. -

QCG 1851 Wmark.Pdf (2.845Mb)

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Calendar for Queen's College, Galway Author(s) Queen's College Galway Publication Date 1851 Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/1485 Downloaded 2021-09-26T06:14:09Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. j!t,;I,,1 ... :-~;.;;"""<,... ... ,.•. Q .......................... ,/ -' ~(;,~, ~" cJTbfr ~ . f ..a, ;) ""~ i61 a...,';')."A'''o •••••••••••••••••• a •• ·.. / . .,-~·'-c..d-P1f..n..-..±;Iotc··iF'·/:..-· :~~.). )v1 w \<\ oJ. t'~lJ'. to, •• l.~ •••••••••••• ~ •. N~f S~~~~~~~D.l~p. Fft~~~~~~:. UAL OF ARITHMETIC, for the Use of' Ools -and -(Jolleg.",·, Ii)' '00 B.m.v. J. G4UJRAIT .... .4.. M .• an the EV. SAMUEL HAUGHTON, A. H., Fellows of Trinity College,D~ .• p. sewed, 28. • :, ... '" , , .»y the sam,e Au~)l"r~·.. .. .... 1 f j MANUAL OF· ·MEGH.:A:,N,I-QS,....:.for.. _the.....lIs.e of Schools and Colleges. Fcap. sewed. 2•. ELEMENTS OF CHEMISTRY, THEORETICAL AND PRACTICAL. Including the most recent Discoveries, and its Application to Medicine and Pharmacy, to Agriculture, and to Ma nufactures. Second Edition, with 230 Wood-cuts. By SIR ROBKRT K4NE, M. D., F. R. S. I vol. thick 8vo. 28,. A TREATISE ON CONIC SECTIONS, contain- ing an Account of the most mollern Algebraic and Geometric Methods. By the REV. GEORGE SALMON, A. M., F. T. C. D. Second Edition. I vo\. 8vo. 12 •. THEOCRITUS. A Selection from the Remains of Theocritus, "Uon. and Moschus; with a Glossary and Prolegomena. By F. H. Ih'GWOOD, A. M .• Head Master of the Royal School, Dun gannon.