Tracking the Residual Voice on the Travelling Fun Fair

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Cultural Geography of Civic Pride in Nottingham

A Cultural Geography of Civic Pride in Nottingham Thomas Alexander Collins Submitted in accordance with the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Leeds School of Geography April 2015 ii The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2015 The University of Leeds and Tom Collins The right of Tom Collins to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. iii Acknowledgements Thanks to David Bell, Nichola Wood and everyone at the School of Geography. Thanks to the people of Nottingham and all the participants I interviewed. Thanks to my family. Thanks to Kate, Dan, Rachel, Martin, Tom, Sam, Luca, Taylor and to everyone who has heard me witter on about civic pride over the past few years. iv Abstract This thesis examines how people perceive, express, contest and mobilise civic pride in the city of Nottingham. Through interviews, participant observation and secondary resource analysis, I explore what people involved in the civic life of the city are proud of about Nottingham, what they consider the city’s (civic) identity to be and what it means to promote, defend and practice civic pride. Civic pride has been under-examined in geography and needs better theoretical and empirical insight. -

Circus Friends Association Collection Finding Aid

Circus Friends Association Collection Finding Aid University of Sheffield - NFCA Contents Poster - 178R472 Business Records - 178H24 412 Maps, Plans and Charts - 178M16 413 Programmes - 178K43 414 Bibliographies and Catalogues - 178J9 564 Proclamations - 178S5 565 Handbills - 178T40 565 Obituaries, Births, Death and Marriage Certificates - 178Q6 585 Newspaper Cuttings and Scrapbooks - 178G21 585 Correspondence - 178F31 602 Photographs and Postcards - 178C108 604 Original Artwork - 178V11 608 Various - 178Z50 622 Monographs, Articles, Manuscripts and Research Material - 178B30633 Films - 178D13 640 Trade and Advertising Material - 178I22 649 Calendars and Almanacs - 178N5 655 1 Poster - 178R47 178R47.1 poster 30 November 1867 Birmingham, Saturday November 30th 1867, Monday 2 December and during the week Cattle and Dog Shows, Miss Adah Isaacs Menken, Paris & Back for £5, Mazeppa’s, equestrian act, Programme of Scenery and incidents, Sarah’s Young Man, Black type on off white background, Printed at the Theatre Royal Printing Office, Birmingham, 253mm x 753mm Circus Friends Association Collection 178R47.2 poster 1838 Madame Albertazzi, Mdlle. H. Elsler, Mr. Ducrow, Double stud of horses, Mr. Van Amburgh, animal trainer Grieve’s New Scenery, Charlemagne or the Fete of the Forest, Black type on off white backgound, W. Wright Printer, Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, 205mm x 335mm Circus Friends Association Collection 178R47.3 poster 19 October 1885 Berlin, Eln Mexikanermanöver, Mr. Charles Ducos, Horaz und Merkur, Mr. A. Wells, equestrian act, C. Godiewsky, clown, Borax, Mlle. Aguimoff, Das 3 fache Reck, gymnastics, Mlle. Anna Ducos, Damen-Jokey-Rennen, Kohinor, Mme. Bradbury, Adgar, 2 Black type on off white background with decorative border, Druck von H. G. -

The World of Smurfs Free

FREE THE WORLD OF SMURFS PDF Matt Murray | 128 pages | 01 Aug 2011 | Abrams | 9781419700729 | English | New York, United States 40+ Best The World of Smurfs images | smurfs, schleich, toy collection Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Preview — The World of Smurfs by Matt. The World of Smurfs A Copy. Hardcoverpages. More Details Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about The World of Smurfsplease sign up. Lists with This Book. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 4. Rating details. More filters. Sort order. Jul 13, Rebecca McNutt rated it it was amazing Shelves: non-fictionhistoryartpop-culture. I'm not exactly what you might call a huge Smurfs fan, but since my mom and sister have been watching the 's cartoon episodes online, it's gotten me to wondering more about the history of these characters and why they became so popular over the years. This large coffee table book was surprisingly interesting and well put together, containing lots of info and photos looking behind-the-scenes and the artists, voice actors and companies that helped bring everything to life. There was a lot of g I'm not exactly what you might call a huge Smurfs fan, but since my mom and sister have been watching the 's cartoon episodes online, it's gotten me to wondering more about the history of these characters and why they became so popular over the years. -

Pre-Owned 1970S Sheet Music

Pre-owned 1970s Sheet Music 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 PLEASE NOTE THE FOLLOWING FOR A GUIDE TO CONDITION AND PRICES PER TITLE ex No marks or deterioration Priced £15. good As appropriate for age of the manuscript. Slight marks on front cover (shop stamp or owner's name). Possible slight marking (pencil) inside.Priced £12. fair Some damage such as edging tears. Reasonable for age of manuscript. Priced £5 Album Contains several songs and photographs of the artist(s). Priced £15+ condition considered. Year Year of print.Usually the same year as copyright (c) but not always. Photo Artist(s) photograph on front cover. n/a No artist photo on front cover LOOKING FOR THESE ARTISTS?You’ve come to the right place for The Bee Gees, Eric Clapton, Russ Conway, John B.Sebastian, Status Quo or even Wings or “Woodstock”. Just look for the artist’s name on the lists below. 1970s TITLE WRITER & COMPOSER CONDITION PHOTO YEAR $7,000 and you Hugo & Luigi/George David Weiss ex The Stylistics 1977 ABBA – greatest hits Album of 19 songs from ex Abba © 1992 B.Andersson/B.Ulvaeus After midnight John J.Cale ex Eric Clapton 1970 After the goldrush Neil Young ex Prelude 1970 Again and again Richard Parfitt/Jackie Lynton/Andy good Status Quo 1978 Bown Ain‟t no love John Carter/Gill Shakespeare ex Tom Jones 1975 Airport Andy McMaster ex The Motors 1976 Albertross Peter Green fair Fleetwood Mac 1970 Albertross (piano solo) Peter Green ex n/a ©1970 All around my hat Hart/Prior/Knight/Johnson/Kemp ex Steeleye Span 1975 All creatures great and Johnny -

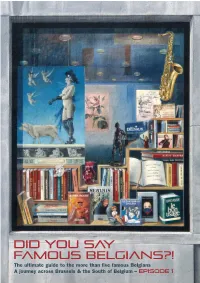

The Ultimate Guide to the More Than Five Famous Belgians a Journey

The ultimate guide to the more than five famous Belgians A journey across Brussels & the South of Belgium – Episode 1 Rue St André, Brussels © Jeanmart.eu/belgiumtheplaceto.be When a Belgian arrives in the UK for the delighted to complete in the near future first time, he or she does not necessarily (hence Episode I in the title). We Belgians expect the usual reaction of the British when are a colourful, slightly surreal people. they realise they are dealing with a Belgian: We invented a literary genre (the Belgian “You’re Belgian? Really?... Ha! Can you name strip cartoon) whose heroes are brilliant more than five famous Belgians?.” When we ambassadors of our vivid imaginations and then start enthusiastically listing some of of who we really are. So, with this Episode 1 our favourite national icons, we are again of Did you say Famous Belgians!? and, by surprised by the disbelieving looks on the presenting our national icons in the context faces of our new British friends.... and we of the places they are from, or that better usually end up being invited to the next illustrate their achievements, we hope to game of Trivial Pursuit they play with their arouse your curiosity about one of Belgium’s friends and relatives! greatest assets – apart, of course, from our beautiful unspoilt countryside and towns, We have decided to develop from what riveting lifestyle, great events, delicious food appears to be a very British joke a means and drink, and world-famous chocolate and of introducing you to our lovely homeland. beer - : our people! We hope that the booklet Belgium can boast not only really fascinating will help you to become the ultimate well- famous characters, but also genius inventors informed visitor, since.. -

Fairs and Music in Post-1945 Britain

This is a repository copy of ‘Only one can rule the night’: Fairs and music in post-1945 Britain. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/125906/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Trowell, I.M. orcid.org/0000-0001-6039-7765 (2018) ‘Only one can rule the night’: Fairs and music in post-1945 Britain. Popular Music History, 10 (3). pp. 262-279. ISSN 1740-7133 https://doi.org/10.1558/pomh.34399 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ O usic in post-1945 Britain Abstract This article charts and examines the relationship between popular music and the British travelling fairground in the post-1945 years. I set out a historical trajectory of the importance of sound and noise within the fairground, and examine how music in the post- 1945 years emerged as an important aspect of this wider soundscape. -

October Events 2014.Xlsx

DATE TITLE NAME DESCRIPTION To promote the adoption of dogs from local shelters, the ASPCA sponsors this important observance. "Make Pet Adoption Your First Optionr" is a message the organization promotes throughout the year Oct 1‐31 ADOPT‐A‐SHELTER‐DOG MONTH ADOPTASHELTERDOG MON in an effort to end the euthanasia of all adoptable animals. 4th annual. American Cheese Month is a celebration of North American artisan, specialty and farmstead cheeses, held in communities throughout North America. From "Meet the Cheesemaker" and "Farmers Market"‐style events, to special cheese tastings and classes at creameries and cheese shops, to cheese‐centric menus featured in restaurants and cafe acus, American Cheese Month is Oct 1‐31 AMERICAN CHEESE MONTH AMERICAN CHEESE MONT celebrated by cheese lovers in communities large and small. A month to remember those who have been injured or who have died as a result of taking antidepressants or at the hands of someone who was on antidepressants. Any adverse reactions or death while taking any drug should be reported to the Food and Drug Administration at Oct 1‐31 ANTIDEPRESSANT DEATH AWARENESS MONTH ANTIDEPRESSANT DEATH www.fda.gov/Safety/Medwatch/default.htm or by calling (800) FDA‐1088. In the fifth inning of game three of the 1932 World Series, with a count of two balls and two strikes and with hostile Cubs fans shouting epithets at him, Babe Ruth pointed to the center field bleachers in Chicago's Wrigley Field and followed up by hitting a soaring home run high above the very spot to which he had just gestured. -

Friends of the Fairground Heritage Trust

Friends of the Fairground Heritage Trust ith the major rides starring in the new museum original organisers in Sheffield, including the National W building a new display for the old building has Fairground Archive, and the Sheffield Galleries and been launched for the 2007 season. With support from the Museums Trust, the popular Pleasurelands exhibition has NEWSLETTER No. 12: JULY 2007 12: JULY NEWSLETTER No. RARE & OUT OF PRINT BOOKS The Trust has a selection of good copies of rare and out of print books available for sale. These can be ordered by post, or have a look at our sales stand at the Great Dorset Steam Fair (in the World’s Fair marquee) or at any of this year’s special events at the Fairground Heritage Centre. Fairground Architecture by David Braithwaite (First Edition, 195pp hardback, published by Hugh Evelyn 1968). £50.00 + £5.30 P&P. Fairground Architecture by David Braithwaite (Second Edition, 195pp soft back with dust jacket, published by Hugh Evelyn 1976). £40.00 + £3.20 P&P. Pat Collins, King of Showmen by Above: Mounts from the Pleasurelands Exhibition. Freda Allen and Ned Williams (Published by Uralia Press 1991, limited been reconstructed using many of the of ephemera relating to Freak Shows, edition of 2500 numbered copies, 265pp original exhibits along with the displays, Menageries and other Shows. hardback). Very scarce £80.00 + £6.00 banners, interactives and audio visuals. Another gallery contains many P&P. The 2007 season was launched by examples of mounts from rides. Like Savage of Kings Lynn by David hosting the Fairground Society’s Annual the rest of the exhibition, this section is Braithwaite (First Edition, 136pp General Meeting. -

Smurfs: Doctor Smurf 20 Kindle

SMURFS: DOCTOR SMURF 20 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Peyo | 48 pages | 01 Mar 2016 | Papercutz | 9781629914336 | English | New York, United States Smurfs: Doctor Smurf 20 PDF Book Android 3. Hefty Smurf warns Master Ludovic that Gargamel is the Smurfs' enemy, but Gargamel convinces Ludovic that it's just a misunderstanding, so the Smurfs grudgingly guide both to the village. So here are 20 little-known facts about the diminutive blue gnomes that might surprise even the smurfiest Smurfs fan. Add the first question. Once, while Papa Smurf was away on some kind of trip, the Smurfs held an election to see who would lead the village while Papa was away. By choosing I Accept , you consent to our use of cookies and other tracking technologies. The unquestioned leader and the smartest of the Smurfs. Handy Smurf voice. After this, several other Smurfs begin to try their own methods like hydrotherapy, physiotherapy, podiatry, etc. User Ratings. Smurf wears a white coat, a stethoscope around his neck and carries a thermometer. User Reviews. Redirected from Docteur Schtroumpf. During this, Doctor Smurf forgets he was attending Clumsy Smurf, who is left naked waiting for his examination. What Happened to Unreal Tournament? Maybe turn them into cat toys for his pet kitty? It's kind of surreal to think that today many of us are playing Cyberpunk , CD Projekt Red's latest He also begins wearing a white coat. Peyo Mar The A. It's another classic Smurfs adventure from master cartoonist Peyo. Tweets by NexusHubZA. Categories :. This wiki. Everything That's New on Netflix in December. -

Leisure, War and Marginal Communities: Travelling Showpeople

Leisure, War and Marginal Communities: Travelling Showpeople and Outdoor Pleasure-Seeking in Britain 1889-1945. Elijah Bell A Thesis Submitted For The Degree of PHD Department Of History University Of Essex i Contents ❖ Contents II ❖ Acknowledgements III ❖ Abstract IV ❖ Glossary of Terms V1 ❖ Introduction 1 ❖ I 20 1885-1914, Persecution to Amalgamation; The Legislative Attack and the Formation of the Showmen’s Guild ❖ II 67 New Opportunities and New Challenges; Regulation, Recreation, and Travelling Showpeople During The Great War ❖ III 115 Relocation, Regulation and Restructuring – Legislation, The Rise Of Municipal Control, and The Showmen’s Guild 1918-1939 ❖ IV 160 An English Tober? – The Culture of Recreation, Societal Contestation, and the Travelling Fairground 1918-1939. ❖ V 204 Outcasts and Funfair Kings – Travelling Fairgrounds During the Second World War 1939-1945. ❖ Conclusion 257 ❖ Appendix 269 ❖ Bibliography 279 ii Acknowledgements I would like to extend my gratitude to all those who have given support, advice, and assistance throughout the completion of this thesis. I would like to thank my family for putting up with the long spells with sporadic contact, the fleeting visits, and the constant chattering about fairgrounds over the last four years. The latter apology is also due to my friends and colleagues, who have been a constant source of inspiration and support. I wish to extend my thanks to everyone who has stopped me in a corridor to ask how things are going, willingly read large sections of text, discussed ideas over a pint, and all who have voiced their belief in me to complete what at times seemed an overwhelming task. -

Film 178D Please Note That Some Items May Not Be Available to View Due to the Age and Condition of the Film and Equipment Needed to View Material

Film 178D Please note that some items may not be available to view due to the age and condition of the film and equipment needed to view material. All requests for access must be made to the NFA prior to visit. 178D1 – Dave Homer Collection 178D2 – Liz Gray Collection 178D3 – Dick Price Collection 178D4 – Geoff Stevens Collection 178D5 – Noel Drewe Collection 178D6 – NFA Collection 178D7 – David Braithwait Collection 178D8 – George Bolesworth Collection 178D9 – Cyril Critchlow Collection 178D10 – BBC Timeshift Series Collection 178D11 – Peter Wellen Collection 178D12 – George Williams Collection 178D13 – Circus Friends Association Collection 178D14 – Smart Family Collection 178D15 – Birt Acres Collection 178D16 – Harry Paulo Family Collection 178D17 – Christopher Palmer Collection 178D18 – O’Beirne Collection 178D19 – Circus250 Archive Collection 178D20 – Vic King Fairground Film Collection 178D21 – Sanger Family Collection 178D22 – Skinning the Cat Collection 178D23 – WGH Rides Collection Dave Homer Collection 178D1 178D1.1 Roundabouts Volume Three Dave Homer Video 1993 180 mins VHS PAL Fairs England Schofield, Jack Locations iclude Glasgow, Sheffield Owlerton, Meadowhall, Stoke-on- Trent, Retford, Grantham, Daisy Nook, Hampstead Heath, kingsbury, Hazel Grove, Cranleigh, Harrogate and Glossop Dave Homer Collection 178D1.2 Roundabouts Volume Four Dave Homer Video 1993 1 160 mins VHS PAL Fairs England Shaw, John Locations include Manchester, Hull, Torquay, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Leeds, Dave Homer Collection 178D1.3 Roundabouts Volume One Dave -

Maps, Charts and Plans 178M

Maps, Charts and Plans 178M 178M1 – Tommy Green Collection 178M2 – Ron Kinder Collection 178M3 – NFA Collection 178M4 – Jack Leeson Collection 178M5 – Arthur Jones Collection 178M6 – Harry Lee Collection 178M7 – David Braithwaite Collection 178M8 – Ilkeston Fair Collection 178M9 – Glen Miller Collection (Newcastle Fair) 178M10 – Leisure Park – Six Piers Collection (Rhyl plus other parks) 178M11– Leisure Park – Six Piers Collection (Battersea General) 178M12– Leisure Park – Six Piers Collection (Battersea Water Chute) 178M13– Leisure Park – Six Piers Collection (Belle Vue) 178M14 – John Bramwell Taylor Collection 178M15 – Orton and Spooner Collection 178M16 – Circus Friends Association Collection 178M17 – Smart Family Collection 178M18 – Frankie Roberto Collection 178M19 – Jack Wilkinson Collection 178M20 – Vic King Collection Tommy Green Collection 178M1 178M1.1 Bolton Summer Fair 1969 A plan of the layout prepared by the Green family Scale 16ft. to 1 inch 600 x 755mm Tommy Green Collection 178M1.2 Bolton New Year’s Fair 1969/70 A plan of the layout prepared by the Green family Bolton, 1969 Scale 16ft. to 1 inch. c.720 x 730mm Tommy Green Collection 178M1.3 Bolton New Year’s Fair 1968-69. [A plan of the layout prepared by the Green family]. Bolton, 1968. Scale 16ft. to 1 inch. c.690x740mm Tommy Green Collection 178M1.4 Bolton.-County Borough of Bolton.-Markets Department Plan of the Wholesale Market (New Year’s Fair 1914) Bolton, Borough Surveyor’s Office, 1896. Scale 16ft. to 1 inch. c.555x755mm A layout of the fair superimposed on the original plan Tommy Green Collection 178M1.5 Bolton.-County Borough of Bolton.-Borough Engineer’s Department Town Hall and surrounding area.