Reasons Why the Japanese Were Fascinated with General Macarthur

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sex Morals and the Law in Ancient Egypt and Babylon James Bronson Reynolds

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 5 | Issue 1 Article 4 1914 Sex Morals and the Law in Ancient Egypt and Babylon James Bronson Reynolds Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation James Bronson Reynolds, Sex Morals and the Law in Ancient Egypt and Babylon, 5 J. Am. Inst. Crim. L. & Criminology 20 (May 1914 to March 1915) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. SEX MORALS AND THE LAW IN ANCIENT EGYPT AND BABYLON. JAMEs BuoNsoN REYNoLDS.' EGYPT. Present knowledge of the criminal law of ancient Egypt relating to sex morals is fragmentary and incomplete in spite of the fact that considerable light has been thrown upon the subject by recent excava- tions and scholarship. We have not yet, however, sufficient data to de- termine the character or moral value of Egyptian law, or of its in- fluence on the Medeterranean world. Egyptian law was, however, elaborately and carefully expanded during the flourishing period of the nation's history.2 Twenty thousand volumes are said to have been written on the Divine law of Hermes, the traditional law-giver of Egypt, whose position is similar to that of Manu in relation to the laws of India. And while it is impossible to trace the direct influence of Egyptian law on the laws of later nations, its indirect influence upon the founders of Grecian law is established beyond ques- tion. -

Overlord Volume 10 - Capítulo 3

Overlord Volume 10 - Capítulo 3 O Império Baharuth Tradutor: União Overlord Revisor: Tio Vlad Parte 1 Albedo estava prestes a partir para o Reino em um dia claro e ensolarado, e Ainz foi ao pátio de sua residência para se despedir dela. Havia cinco carruagens luxuosas estacionadas lá. Uma delas era para Albedo e outra para sua bagagem. Uma das carruagens restantes continha presentes para o rei, para dar ênfase na diferença entre o poder do Reino e do Reino Arcano. Em torno destas carruagens estavam 20 Cavaleiros da Morte que Ainz tinha criado. Teria sido muito mais fácil apenas tele transportá-los para o Reino, mas haviam escolhido não fazer isso. Albedo e seu grupo eram os responsáveis por demonstrar o poder do Reino Arcano. Parte disso significava usar monstros no lugar de cavalos para puxar as carruagens. Uma ameaça implícita, por assim dizer. "Então, Ainz-sama, por favor, se cuide por um tempo." "Umu, tenha cuidado. Ainda não encontramos as pessoas que controlaram Shalltear. É por isso que não podemos excluir a possibilidade de que eles possam estar tentando controlá-la, e então usá-la como parte de uma grande aposta para infligir danos maciços em Nazarick. " "Claro. Eu vou ser cuidadosa e nunca deixarei isso acontecer comigo." Albedo estava abraçando um item de classe mundial em seu peito. "Eu acredito que possuir isso deva eliminar o risco de ser hipnotizada por um Item de classe mundial. No entanto, o inimigo pode não estar limitado a usar apenas esse item. Além disso, embora este Item de Classe Mundial que você possui é o mais poderoso contra objetos físicos, não se esqueça que não é muito útil contra alvos individuais." "É assim mesmo? Mas, usarei isto como uma arma principal assim que mudar sua forma..." "É mais fraco do que um item de classe divina especializado. -

Read Overlord, Vol. 7 (Light Novel) (Overlord Light Novels, #7) Online, Download Best Book Overlord, Vol

Overlord, Vol. 7 (light novel) (Overlord Light Novels, #7) by Kugane Maruyama, Read PDF Overlord, Vol. 7 (light novel) (Overlord Light Novels, #7) Online, Download PDF Overlord, Vol. 7 (light novel) (Overlord Light Novels, #7), Full PDF Overlord, Vol. 7 (light novel) (Overlord Light Novels, #7), All Ebook Overlord, Vol. 7 (light novel) (Overlord Light Novels, #7), PDF and EPUB Overlord, Vol. 7 (light novel) (Overlord Light Novels, #7), PDF ePub Mobi Overlord, Vol. 7 (light novel) (Overlord Light Novels, #7), Reading PDF Overlord, Vol. 7 (light novel) (Overlord Light Novels, #7), Book PDF Overlord, Vol. 7 (light novel) (Overlord Light Novels, #7), Read online Overlord, Vol. 7 (light novel) (Overlord Light Novels, #7), Overlord, Vol. 7 (light novel) (Overlord Light Novels, #7) Kugane Maruyama pdf, by Kugane Maruyama Overlord, Vol. 7 (light novel) (Overlord Light Novels, #7), book pdf Overlord, Vol. 7 (light novel) (Overlord Light Novels, #7), by Kugane Maruyama pdf Overlord, Vol. 7 (light novel) (Overlord Light Novels, #7), Kugane Maruyama epub Overlord, Vol. 7 (light novel) (Overlord Light Novels, #7), pdf Kugane Maruyama Overlord, Vol. 7 (light novel) (Overlord Light Novels, #7), the book Overlord, Vol. 7 (light novel) (Overlord Light Novels, #7), Kugane Maruyama ebook Overlord, Vol. 7 (light novel) (Overlord Light Novels, #7), Overlord, Vol. 7 (light novel) (Overlord Light Novels, #7) E-Books, Online Overlord, Vol. 7 (light novel) (Overlord Light Novels, #7) Book, pdf Overlord, Vol. 7 (light novel) (Overlord Light Novels, #7), Overlord, Vol. 7 (light novel) (Overlord Light Novels, #7) E-Books, Overlord, Vol. 7 (light novel) (Overlord Light Novels, #7) Online Read Best Book Online Overlord, Vol. -

Download Overlord Vol 2 Light Novel Pdf Book by Kugane Maruyama

Download Overlord Vol 2 light novel pdf book by Kugane Maruyama You're readind a review Overlord Vol 2 light novel ebook. To get able to download Overlord Vol 2 light novel you need to fill in the form and provide your personal information. Ebook available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Gather your favorite ebooks in your digital library. * *Please Note: We cannot guarantee the availability of this file on an database site. Book Details: Original title: Overlord, Vol. 2 - light novel Series: Overlord (Book 2) 256 pages Publisher: Yen On (September 27, 2016) Language: English ISBN-10: 9780316363914 ISBN-13: 978-0316363914 ASIN: 031636391X Product Dimensions:5.8 x 1 x 8.8 inches File Format: PDF File Size: 1336 kB Description: It has been a week since Momonga logged in to his favorite RPG one last time and stranded himself there. Now he leads his guild as the Ainz Ooal Gown overlord. Finding himself in dire need of better information, he travels disguised as an adventurer to the walled city of E-Rantel, with Narberal the battle maid at his side. The pair accept a mission... Review: I liked the first books premise and so I ordered the second book which I also liked but I thought the book was too short, it barely got started rolling along and it was over already. The main character is doing okay at coping with his situation but seems t be realizing just how limited mentally his minions may be as they one track minds keep glossing... Ebook File Tags: light novels pdf, light novel pdf, looking forward pdf, main character pdf, great book pdf, enjoy -

Learning from SHOGUN

Learning from Shǀgun Japanese History and Western Fantasy Edited by Henry Smith Program in Asian Studies University of California, Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, California 93106 Contents Designed by Marc Treib Contributors vi Copyright © 1980 by Henry D. Smith II Maps viii for the authors Preface xi Distributed by the Japan Society, 333 East 47th Street, New York, Part I: The Fantasy N.Y. 10017 1 James Clavell and the Legend of the British Samurai 1 Henry Smith 2 Japan, Jawpen, and the Attractions of an Opposite 20 Illustrations of samurai armor are David Plath from Murai Masahiro, Tanki yǀryaku 3 Shǀgun as an Introduction to Cross-Cultural Learning 27 (A compendium for the mounted Elgin Heinz warrior), rev. ed., 1837, woodblock edition in the Metropolitan Museum Part II: The History of Art, New York 4 Blackthorne’s England 35 Sandra Piercy 5 Trade and Diplomacy in the Era of Shǀgun 43 Ronald Toby 6 The Struggle for the Shogunate 52 Henry Smith 7 Hosokawa Gracia: A Model for Mariko 62 Chieko Mulhern This publication has been supported by Part III: The Meeting of Cultures grants from: 8 Death and Karma in the World of Shǀgun 71 Consulate General of Japan, Los William LaFleur Angeles 9 Learning Japanese with Blackthorne 79 Japan-United States Susan Matisoff Friendship Commission 10 The Paradoxes of the Japanese Samurai 86 Northeast Asia Council, Henry Smith Association for Asian Studies 11 Consorts and Courtesans: The Women of Shǀgun 99 USC-UCLA Joint East Asia Henry Smith Studies Center 12 Raw Fish and a Hot Bath: Dilemmas of Daily Life 113 Southern California Conference on Henry Smith International Studies Who’s Who in Shǀgun 127 Glossary 135 For Further Reading 150 Postscript: The TV Transformation 161 vi Contributors vii Sandra Piercy is a graduate student in English history of the Tudor- Stuart period at the University of California, Santa Barbara. -

Meitei-Naga Relationship

Imphal Times Supplementary issue 2 Editorial MEITEI-NAGA RELATIONSHIP Wednesday, September 19, 2018 By - Amung Hungyo Having observed all the hues and So much so, the narrow plains severed Naga’s land to make the (A Naga Public) cries in both the print and electronic comprising 20% of the present state of Manipur, Ukhrul Spirit of Hijam Irabot still runs media about the slogans of bandhs, geographical area have 40 MLAs Assam and Arunachal Pradesh. strikes, dharnas and blockades, I while the rest 80% of the total land Keep in mind, the compact and Will Naga Political Solution in Manipur Journalists find that “the Meitei community is area is given just 20 MLAs. Only contiguous Naga country was negatively impact Sanaleibak? really very proud to say that they in this state, mob is the ruler and never allotted by the The Meitei’s Manipur or have 2000 years of history.” I authority in any matter. One Government of India nor was Kangleipak or Sanaleibak will lose Media will resume to play its part appreciate their love for their land cannot easily forget the incident loaned by any Manipur Rajas. nothing by removing Naga and history. I have no objection to like the one which happened in So, India cannot manipulate the territory from the present Map of the Meitei’s having 2000 years or December, 2012 popularly known Nagas’ fate like this. Among Manipur. It can be still larger than Almost every section of the Manipuri society including 7000 years history. What I wonder as Momoko Incident of Chandel many others, we are narrating Goa. -

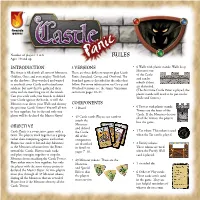

INTRODUCTION Objective 3 Versions

® fireside games ® Number of players: 1 to 6 RS ULE Ages: 10 and up INTRODUCTION 3 Versions • 6 Walls with plastic stands: Walls keep Monsters out The forest is filled with all sorts of Monsters. There are three different ways to play Castle of the Castle Goblins, Orcs, and even mighty Trolls lurk Panic: Standard, Co-op, and Overlord. The and can be in the shadows. They watched and waited Standard game is described in the rules that rebuilt if they as you built your Castle and trained your follow. For more information on Co-op and are destroyed. soldiers, but now they’ve gathered their Overlord versions, see the Game Variations (The first time Castle Panic is played, the army and are marching out of the woods. section on pages 10–11. plastic stands will need to be put on the Can you work with your friends to defend Walls and Towers.) your Castle against the horde, or will the Monsters tear down your Walls and destroy Components the precious Castle Towers? You will all win • 1 Board • 6 Towers with plastic stands: or lose together, but in the end only one Towers are the heart of the player will be declared the Master Slayer! Castle. If the Monsters destroy • 49 Castle cards: Players use cards to all of the Towers, the players attack the lose the game. Monsters OBJectiVE and defend Castle Panic is a cooperative game with a the Castle. • 1 Tar token: This token is used twist. The players work together as a group All of the when the Tar card is played. -

Carrion Crown Session Summary 02/02/2014

Carrion Crown Summary 02/02/2014 Carrion Crown Session Summary 02/02/2014 Attendance Chris is busying himself with readying the table when Bruce pings in on the Google Hangout to report that while he’s still in Richardson, he’ll be showing up in Round Rock in just a moment. Chris observes that the technology to support that request is not quite in place yet, though maybe next year it will be. He notes that Bruce will be sad that he missed out on the donuts, theatrically gesturing at the two boxes of donuts he has procured for the group. They then migrate to the subject of hummus and its lack of change in appearance through the entire digestive process. Paul appears in time to report that he cooked some tomatoes down “English style”, by which he means he cooked them until they turned pink and mushy. But he also brought donuts! “English style” donuts! He adds them to the pile. Patrick is not choosy: “Mmmm! Donuts!” Ernest shows up a bit later with a cry of triumph! Everyone hopes that he didn’t bring donuts. He assures them that he did not! He brought kolaches and red velvet cake! The pile of baked goods reaches epic proportions. Matt appears to find everyone else staring at him with a sense of almost palpable expectation. Chris even turns the webcam around so Bruce can stare at him. He asks somewhat tenuously, “What’s up?” Soon enough, he learns that he is one of the few folks remaining in the group who have not had a chance to receive the Official Turner Late Christmas Gift. -

Indian Serpent Lore Or the Nagas in Hindu Legend And

D.G.A. 79 9 INDIAN SERPENT-LOEE OR THE NAGAS IN HINDU LEGEND AND ART INDIAN SERPENT-LORE OR THE NAGAS IN HINDU LEGEND AND ART BY J. PH. A'OGEL, Ph.D., Profetsor of Sanskrit and Indian Archirology in /he Unircrsity of Leyden, Holland, ARTHUR PROBSTHAIN 41 GREAT RUSSELL STREET, LONDON, W.C. 1926 cr," 1<A{. '. ,u -.Aw i f\0 <r/ 1^ . ^ S cf! .D.I2^09S< C- w ^ PRINTED BY STEPHEN AUSTIN & SONS, LTD., FORE STREET, HERTFORD. f V 0 TO MY FRIEND AND TEACHER, C. C. UHLENBECK, THIS VOLUME IS DEDICATED. PEEFACE TT is with grateful acknowledgment that I dedicate this volume to my friend and colleague. Professor C. C. Uhlenbeck, Ph.D., who, as my guru at the University of Amsterdam, was the first to introduce me to a knowledge of the mysterious Naga world as revealed in the archaic prose of the Paushyaparvan. In the summer of the year 1901 a visit to the Kulu valley brought me face to face with people who still pay reverence to those very serpent-demons known from early Indian literature. In the course of my subsequent wanderings through the Western Himalayas, which in their remote valleys have preserved so many ancient beliefs and customs, I had ample opportunity for collecting information regarding the worship of the Nagas, as it survives up to the present day. Other nations have known or still practise this form of animal worship. But it would be difficult to quote another instance in which it takes such a prominent place in literature folk-lore, and art, as it does in India. -

610 96566 001 EN Serpent Kingd

™ Sample file 620_96566_SerpentKingdom3.indd 1 5/11/04, 11:57:14 AM Sample file TABLE OF CONTENTS Slavery . 57 The Insidious Plot . 137 The Scaled Races. 58 Slithering into a New Area. 137 Contents Dwellings . 58 Into the Open . 138 Introduction . 4 Sarrukh Characters . 58 PCs in the Middle. 138 Abbreviations . 4 Magic of the Sarrukh . 59 Avenging Snakes . 138 What You Need to Play . 4 Deities of the Sarrukh. 59 Religious Differences . 139 The Progenitors . 5 Sacrifi ce . 59 The Old Trick . 139 Scaleless Ones . 5 The Fragmentation Orders of the Faith . 139 Scaled Ones . 5 of the World Serpent . 59 Snake Companions. 139 The Insidious Threat. 6 Relations with Other Races . 60 Familiars . 140 The Ideal . 6 Sarrukh Equipment. 60 Secret Organizations . 140 Covert Control . 6 Sarrukh Encounters . 60 Major Yuan-ti NPCs . 140 Pil’it’ith. 60 Zstulkk Ssarmn. 142 Chapter 1: Yuan-Ti . 8 Nhyris D’Hothek . 143 Overview . 8 Chapter 6: Monsters . 62 Description . 8 Amphisbaena. 62 Chapter 9: Feats. 144 Purebloods . 8 Deathcoils . 63 Feat Descriptions . 144 Halfbloods . 8 Dinosaur . 64 Abominations . 8 Ceratosaur . 64 Chapter 10: Equipment . 148 Anathemas . 9 Pteranadon . 65 Armor . 148 Other Yuan-ti Subraces . 9 Stegosaurus. 66 Weapons. 149 Racial History. 9 Jaculi. 66 Special Substances . 149 Outlook . 9 Lizard King/Queen . 68 Poisons . 149 Yuan-ti Society . 10 Lycanthrope, Wereserpent . 69 Lizardfolk Poisons . 149 Yuan-ti Characters . 17 Mlarraun. 70 Yuan-ti Poisons . 149 Purebloods . 17 Muckdweller . 71 Osssra . 149 Tainted Ones and Broodguards . 17 Naga . 72 Magic Items . 151 Magic of the Yuan-ti. 18 Banelar Naga. -

Religious Worship Era's in Kas'mira {Kashmir} Naga's

RELIGIOUS WORSHIP ERA’S IN KAS’MIRA {KASHMIR} NAGA’S - ARYAN’S TO KUL DEVI’S “The place is more beautiful than the heaven and is the benefactor of supreme bliss and happiness. It seems to me that I am taking a bath in the lake of nectar here.” - {Translated} Sanskrit Poet Kalidasa { This piece of our religious history is for my Grand-Daughter Praharshita, which gives a peep into way of life of Naga’s; Manus {Aryans} , their connection with original inhabitants and immigration to various parts of Bharatvarsha and Kas’mira; Vedic Religion and evolution of a mixed culture and religion of Naga’s and Aryans in Kas’mira. Which transited through Buddhism, Shaivism and finally to Kul Devi worship. } Kas’mira - The Vale of Gods And Evolution The Vale of Gods. Ancient Greeks called Kas’mira ‘Kasperia’ and the Chinese pilgrim Huen- Tsang, who visited the valley around 631 AD, called it “KaShi-Mi-Lo”. Sir Walter Lawrence writes this about Kas’mira; “The valley is an emerald set in pearls; a land of lakes, clear streams, green turf, magnificent trees and mighty mountains where the air is cool, and the water sweet …”. Sir Francis Young Husband, adventurer, who blazed trail across Himalayas writes about a temple in Kas’mira: “…... built on the most sublime site occupied by any building in the world-finer than the site of Parthenon, or of the Taj Mahal, or of Saint Peters or of the Escurial…...the snowy ranges which bound it-so situated in fact as to be encircled, yet not overwhelmed by snowy mountains-stand the ruins of a temple second only to the Egyptians in massiveness and strength, and to the Greeks in elegance and grace…. -

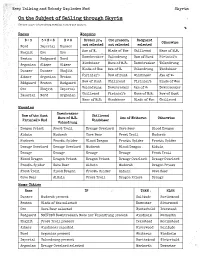

On the Subject of Sailing Through Skyrim

Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes Mod Skyrim On the Subject of Sailing through Skyrim Use the power of the Cheat Sheet to disarm the module. Races Weapons B < 3 3 ≤ B < 6 B ≥ 6 Breton pr., Orc present, Redguard Otherwise not selected not selected selected Nord Imperial Dunmer Axe of W. Blade of Woe Chillrend Mace of M.B. Khajiit Orc Orc Dawnbreaker Volendrung Bow of Hunt Firiniel’s Breton Redguard Nord Windshear Mace of M.B. Dawnbreaker Volendrung Argonian Altmer Altmer Blade of Woe Axe of W. Volendrung Windshear Dunmer Dunmer Khajiit Firiniel’s Bow of Hunt Windshear Axe of W. Altmer Argonian Breton Bow of Hunt Chillrend Firiniel’s Blade of Woe Redguard Breton Redguard Volendrung Dawnbreaker Axe of W. Dawnbreaker Orc Khajiit Imperial Chillrend Firiniel’s Mace of M.B. Bow of Hunt Imperial Nord Argonian Mace of M.B. Windshear Blade of Woe Chillrend Enemies Dawnbreaker Bow of the Hunt Chillrend Mace of M.B. Axe of Whiterun Otherwise Firiniel’s End Windshear Volendrung Dragon Priest Frost Troll Draugr Overlord Cave Bear Blood Dragon Alduin Mudcrab Cave Bear Frost Troll Mudcrab Mudcrab Frostb. Spider Blood Dragon Frostb. Spider Frostb. Spider Draugr Overlord Draugr Overlord Mudcrab Blood Dragon Alduin Draugr Draugr Draugr Draugr Frost Troll Blood Dragon Dragon Priest Dragon Priest Draugr Overlord Draugr Overlord Frostb. Spider Cave Bear Alduin Mudcrab Dragon Priest Frost Troll Blood Dragon Frostb. Spider Alduin Cave Bear Cave Bear Alduin Frost Troll Dragon Priest Draugr Home Cities Race IF THEN ↓ ELSE Dunmer Mudcrab present Solitude Rorikstead