Arxiv:1905.02007V1 [Q-Bio.NC] 6 May 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SELF-PROPAGATING, NON-SYNAPTIC HIPPOCAMPAL WAVES RECRUIT NEURONS by ELECTRIC FIELD COUPLING by RAJAT SHAMACHAR SHIVACHARAN Submi

SELF-PROPAGATING, NON-SYNAPTIC HIPPOCAMPAL WAVES RECRUIT NEURONS BY ELECTRIC FIELD COUPLING By RAJAT SHAMACHAR SHIVACHARAN Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Thesis Advisor: Dominique M. Durand, PhD Department of Biomedical Engineering CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May 2019 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis dissertation of Rajat Shamachar Shivacharan candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy*. Committee Chair Jeffrey R. Capadona Thesis Advisor/Committee Member Dominque M. Durand Committee Member Cameron C. McIntyre Committee Member Hillel J. Chiel Date of Defense: April 8th, 2019 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. Dedication To my great grandfathers, Mr. Doddappa Acharya and Mr. Shilipi Shamachar; to my grandparents Mr. Y.S. Shamachar & Mrs. Lalitha, and Mr. H.D. Ramakrishna Sastry & Justice B.S. Indrakala; for being exemplary role models for me, and for being the luminaries of my family. To my Mom & Dad, my brother Manju, our loving, four-legged pup Rocky, and the rest of my family and friends near and far; for your unwavering love and support throughout my adventures. Table of Contents Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................... i List of Figures ................................................................................................................. -

Climbing Fiber Synapses Rapidly Inhibit Neighboring Purkinje Cells Via Ephaptic Coupling

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2019.12.17.879890; this version posted December 18, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Climbing fiber synapses rapidly inhibit neighboring Purkinje cells via ephaptic coupling Kyung-Seok Han*, Christopher H. Chen*, Mehak M. Khan, Chong Guo and Wade G. Regehr1 Department of Neurobiology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA *Co-first author 1Lead Contact Correspondence: [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2019.12.17.879890; this version posted December 18, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract Climbing fibers (CFs) from the inferior olive (IO) provide strong excitatory inputs onto the dendrites of cerebellar Purkinje cells (PC), and trigger distinctive responses known as complex spikes (CSs). We find that in awake, behaving mice, a CS in one PC suppresses conventional simple spikes (SSs) in neighboring PCs for several milliseconds. This involves a novel form of ephaptic coupling, in which an excitatory synapse nonsynaptically inhibits neighboring cells by generating large negative extracellular signals near their dendrites. The distance dependence of CS-SS ephaptic signaling, combined with the known divergence of CF synapses made by IO neurons, allows a single IO neuron to influence the output of the cerebellum by synchronously suppressing the firing of potentially over one hundred PCs. Optogenetic studies in vivo and dynamic clamp studies in slice indicate that such brief PC suppression can effectively promote firing in neurons in the deep cerebellar nuclei and motor thalamus. -

Thenerveimpulse05.Pdf

The nerve impulse. INTRODUCTION Axons are responsible for the transmission of information between different points of the nervous system and their function is analogous to the wires that connect different points in an electric circuit. However, this analogy cannot be pushed very far. In an electrical circuit the wire maintains both ends at the same electrical potential when it is a perfect conductor or it allows the passage of an electron current when it has electrical resistance. As we will see in these lectures, the axon, as it is part of a cell, separates its internal medium from the external medium with the plasma membrane and the signal conducted along the axon is a transient potential difference1 that appears across this membrane. This potential difference, or membrane potential, is the result of ionic gradients due to ionic concentration differences across the membrane and it is modified by ionic flow that produces ionic currents perpendicular to the membrane. These ionic currents give rise in turn to longitudinal currents closing local ionic current circuits that allow the regeneration of the membrane potential changes in a different region of the axon. This process is a true propagation instead of the conduction phenomenon occurring in wires. To understand this propagation we will study the electrical properties of axons, which include a description of the electrical properties of the membrane and how this membrane works in the cylindrical geometry of the axon. Much of our understanding of the ionic mechanisms responsible for the initiation and propagation of the action potential (AP) comes from studies on the squid giant axon by A. -

Spatial Extent of Neurons: Dendrites and Axons

Spatial extent of neurons: dendrites and axons Morphological diversity of neurons Cortical pyramidal cell Purkinje cell Retinal ganglion cells Motoneurons Dendrites: spiny vs non-spiny Recording and simulating dendrites Axons - myelinated vs unmyelinated Axons - myelinated vs unmyelinated • Myelinated axons: – Long-range axonal projections (motoneurons, long-range cortico-cortical connections in white matter, etc) – Saltatory conduction; – Fast propagation (10s of m/s) • Unmyelinated axons: – Most local axonal projections – Continuous conduction – Slower propagation (a few m/s) Recording from axons Recording from axons Recording from axons - where is the spike generated? Modeling neuronal processes as electrical cables • Axial current flowing along a neuronal cable due to voltage gradient: V (x + ∆x; t) − V (x; t) = −Ilong(x; t)RL ∆x = −I (x; t) r long πa2 L where – RL: total resistance of a cable of length ∆x and radius a; – rL: specific intracellular resistivity • ∆x ! 0: πa2 @V Ilong(x; t) = − (x; t) rL @x The cable equation • Current balance in a cylinder of width ∆x and radius a • Axial currents leaving/flowing into the cylinder πa2 @V @V Ilong(x + ∆x; t) − Ilong(x; t) = − (x + ∆x; t) − (x; t) rL @x @x • Ionic current(s) flowing into/out of the cell 2πa∆xIion(x; t) • Capacitive current @V I (x; t) = 2πa∆xc cap M @t • Kirschoff law Ilong(x + ∆x; t) − Ilong(x; t) + 2πa∆xIion(x; t) + Icap(x; t) = 0 • In the ∆x ! 0 limit: @V a @2V cM = 2 − Iion @t 2rL @x Compartmental appoach Compartmental approach Modeling passive dendrites: Cable equation -

Structure and Function Relationship in Nerve Cells & Membrane Potential

Structure and Function Relationship in Nerve Cells & Membrane Potential Asist. Prof. Aslı AYKAÇ NEU Faculty of Medicine Biophysics Nervous System Cells • Glia – Not specialized for information transfer – Support neurons • Neurons (Nerve Cells) – Receive, process, and transmit information Neurons • Neuron Doctrine – The neuron is the functional unit of the nervous system • Specialized cell type – have very diverse in structure and function Neuron: Structure/Function • designed to receive, process, and transmit information – Dendrites: receive information from other neurons – Soma: “cell body,” contains necessary cellular machinery, signals integrated prior to axon hillock – Axon: transmits information to other cells (neurons, muscles, glands) • Information travels in one direction – Dendrite → soma → axon How do neurons work? • Function – Receive, process, and transmit information – Conduct unidirectional information transfer • Signals – Chemical – Electrical Membrane Potential Because of motion of positive and negative ions in the body, electric current generated by living tissues. What are these electrical signals? • receptor potentials • synaptic potentials • action potentials Why are these electrical signals important? These signals are all produced by temporary changes in the current flow into and out of cell that drives the electrical potential across the cell membrane away from its resting value. The resting membrane potential The electrical membrane potential across the membrane in the absence of signaling activity. Two type of ions channels in the membrane – Non gated channels: always open, important in maintaining the resting membrane potential – Gated channels: open/close (when the membrane is at rest, most gated channels are closed) Learning Objectives • How transient electrical signals are generated • Discuss how the nongated ion channels establish the resting potential. -

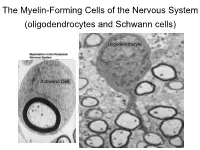

The Myelin-Forming Cells of the Nervous System (Oligodendrocytes and Schwann Cells)

The Myelin-Forming Cells of the Nervous System (oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells) Oligodendrocyte Schwann Cell Oligodendrocyte function Saltatory (jumping) nerve conduction Oligodendroglia PMD PMD Saltatory (jumping) nerve conduction Investigating the Myelinogenic Potential of Individual Oligodendrocytes In Vivo Sparse Labeling of Oligodendrocytes CNPase-GFP Variegated expression under the MBP-enhancer Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Ant Commissure Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Piriform Cortex Corpus Callosum Ant Commissure Characterization of Oligodendrocyte Morphology Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Caudate Putamen Cerebellum Brain Stem Spinal Cord Oligodendrocytes in disease: Cerebral Palsy ! CP major cause of chronic neurological morbidity and mortality in children ! CP incidence now about 3/1000 live births compared to 1/1000 in 1980 when we started intervening for ELBW ! Of all ELBW {gestation 6 mo, Wt. 0.5kg} , 10-15% develop CP ! Prematurely born children prone to white matter injury {WMI}, principle reason for the increase in incidence of CP ! ! 12 Cerebral Palsy Spectrum of white matter injury ! ! Macro Cystic Micro Cystic Gliotic Khwaja and Volpe 2009 13 Rationale for Repair/Remyelination in Multiple Sclerosis Oligodendrocyte specification oligodendrocytes specified from the pMN after MNs - a ventral source of oligodendrocytes -

Gathering at the Nodes

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS GLIA Gathering at the nodes Saltatory conduction — the process by which that are found at the nodes of Ranvier, where action potentials propagate along myelinated they interact with Na+ channels. When the nerves — depends on the fact that voltage- authors either disrupted the localization of gated Na+ channels form clusters at the nodes gliomedin by using a soluble fusion protein of Ranvier, between sections of the myelin that contained the extracellular domain of sheath. New findings from Eshed et al. show neurofascin, or used RNA interference to that Schwann cells produce a protein called suppress the expression of gliomedin, the gliomedin, and that this is responsible for characteristic clustering of Na+ channels at the clustering of these channels. the nodes of Ranvier did not occur. The formation of the nodes of Ranvier is Aggregation of the domain of gliomedin specified by the myelinating cells, not the that binds neurofascin and NrCAM on the axons, and an important component of this surface of purified neurons also caused process in the peripheral nervous system the clustering of neurofascin, Na+ channels is the extension of microvilli by Schwann and other nodal proteins. These findings cells. These microvilli contact the axons at support a model in which gliomedin on the nodes, and it is here that the Schwann References and links Schwann cell microvilli binds to neurofascin ORIGINAL RESEARCH PAPER Eshed, Y. et al. Gliomedin cells express the newly discovered protein and NrCAM on axons, causing them to mediates Schwann cell–axon interaction and the molecular gliomedin. cluster at the nodes of Ranvier, and leading assembly of the nodes of Ranvier. -

New Plasmon-Polariton Model of the Saltatory Conduction

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.17.910596; this version posted January 20, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Manuscript submitted to BiophysicalJournal Article New plasmon-polariton model of the saltatory conduction W. A. Jacak1,* ABSTRACT We propose a new model of the saltatory conduction in myelinated axons. This conduction of the action potential in myelinated axons does not agree with the conventional cable theory, though the latter has satisfactorily explained the electro- signaling in dendrites and in unmyelinated axons. By the development of the wave-type concept of ionic plasmon-polariton kinetics in axon cytosol we have achieved an agreement of the model with observed properties of the saltatory conduction. Some resulting consequences of the different electricity model in the white and the gray matter for nervous system organization have been also outlined. SIGNIFICANCE Most of axons in peripheral nervous system and in white matter of brain and spinal cord are myelinated with the action potential kinetics speed two orders greater than in dendrites and in unmyelinated axons. A decrease of the saltatory conduction velocity by only 10% ceases body functioning. Conventional cable theory, useful for dendrites and unmyelinated axon, does not explain the saltatory conduction (discrepancy between the speed assessed and the observed one is of one order of the magnitude). We propose a new nonlocal collective mechanism of ion density oscillations synchronized in the chain of myelinated segments of plasmon-polariton type, which is consistent with observations. -

The Calyx of Held

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by RERO DOC Digital Library Cell Tissue Res (2006) 326:311–337 DOI 10.1007/s00441-006-0272-7 REVIEW The calyx of Held Ralf Schneggenburger & Ian D. Forsythe Received: 6 April 2006 /Accepted: 7 June 2006 / Published online: 8 August 2006 # Springer-Verlag 2006 Abstract The calyx of Held is a large glutamatergic A short history of the calyx of Held synapse in the mammalian auditory brainstem. By using brain slice preparations, direct patch-clamp recordings can The size of a synapse is a significant technical constraint for be made from the nerve terminal and its postsynaptic target electrophysiological recording. The large dimensions of (principal neurons of the medial nucleus of the trapezoid some invertebrate synapses have been exploited to provide body). Over the last decade, this preparation has been considerable insight into presynaptic function (Llinas et al. increasingly employed to investigate basic presynaptic 1972; Augustine et al. 1985; Young and Keynes 2005). mechanisms of transmission in the central nervous system. However, the progress of similar studies in vertebrates was We review here the background to this preparation and long hampered by the technical difficulty of presynaptic summarise key findings concerning voltage-gated ion recording from small nerve terminals. Over the last 50 years, channels of the nerve terminal and the ionic mechanisms a range of preparations have contributed to our understand- involved in exocytosis and modulation of transmitter ing of presynaptic mechanisms, from the neuromuscular release. The accessibility of this giant terminal has also junction (Katz 1969) to chromaffin cells (Neher and Marty permitted Ca2+-imaging and -uncaging studies combined 1982), chick ciliary ganglion (Martin and Pilar 1963; with electrophysiological recording and capacitance mea- Stanley and Goping 1991), neurohypophysial nerve termi- surements of exocytosis. -

The Nervous System Action Potentials

The Nervous System Action potentials Jennifer Carbrey Ph.D. Department of Cell Biology Nervous System Cell types neurons glial cells Methods of communication in nervous system – action potentials How the nervous system is organized central vs. peripheral Voltage Gated Na+ & K+ Channels image by Rick Melges, Duke University Depolarization of the membrane is the stimulus which leads to both channels opening. To reset the Na+ channel from inactive to closed need to repolarize the membrane. Refractory period is when Na+ channels are inactivated. Action Potentials stage are rapid, “all or none” and do not decay over 1 2 3 4 5 distances top image by image by Chris73 (modified), http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Action_potential_%28no_labels%29.svg, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license bottom image by Rick Melges, Duke University Unidirectional Propagation of AP image by Rick Melges, Duke University Action potentials move one-way along the axon because of the absolute refractory period of the voltage gated Na+ channel. Integration of Signals Input: Dendrites: ligand gated ion channels, some voltage gated channels; graded potentials Cell body (Soma): ligand gated ion channels; graded potentials Output: Axon: voltage gated ion channels, action potentials Axon initial segment: highest density of voltage gated ion channels & lowest threshold for initiating an action potential, “integrative zone” Axon Initial Segment image by Rick Melges, Duke University Integration of signals at initial segment Saltatory Conduction Node of Ranvier Na+ action potential Large diameter, myelinated axons transmit action potentials very rapidly. Voltage gated channels are concentrated at the nodes. Inactivation of voltage gated Na+ channels insures uni-directional propagation along the axon. -

Neuronal Signaling Neuroscience Fundamentals > the Nerve Cell > the Nerve Cell

Neuronal Signaling Neuroscience Fundamentals > The Nerve Cell > The Nerve Cell NEURONAL SIGNALING SUMMARY ACTION POTENTIALS See: Action Potentials Key Features • All-or-nothing events • Self-propagating • Conduction speed determined by axon diameter (thicker means faster) and amount of myelination (more myelin means faster transmission). CHEMICAL SYNAPSE Steps of Chemical Synapsis 1) The action potential travels down axon of presynaptic neuron. 2) Vesicle fuses with plasma membrane and releases neurotransmitter into the synaptic cleft. 3) Neurotransmitters bind to ligand-gated ion channels, opening them. 4) Ions entering through the open channels cause a depolarization of the membrane, opening voltage-gated ion channels. 5) Ions pass through these voltage-gated ion channels, causing further depolarization of the membrane. 6) This depolarization (action potential) travels along the membrane as more voltage-gated ion channels are opened. ELECTRICAL SYNAPSE • Cytoplasms of adjacent neurons are connected, allowing ions (and action potentials) to travel directly to the next cell. NEURONAL CODING OF STIMULUS STRENGTH Action Potential Frequency • Stimulus strength is based on frequency of action potentials. Action Potential Strength • Strong stimuli can produce another action potential during the relative refractory period. 1 / 7 ABSOLUTE REFRACTORY PERIOD No further action potentials • Voltage-gated sodium channels are open or inactivated so another stimulus, no matter its strength, CANNOT elicit another action potential. RELATIVE REFRACTORY -

1 Title Neuronal Coupling by Endogenous Electric Fields

Title Neuronal coupling by endogenous electric fields: Cable theory and applications to coincidence detector neurons in the auditory brainstem Authors Joshua H. Goldwyn1,2,3 John Rinzel1,2 Contributions JHG and JR designed study, analyzed data, and wrote manuscript. JHG performed simulations. Affiliations 1 Center for Neural Science, New York University, New York, NY, United States 2 Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences, New York University, New York, NY, United States 3 Department of Mathematics, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, United States Running Head Neuronal coupling by endogenous electric fields Address for Correspondence Joshua H. Goldwyn 100 Math Tower 231 West 18th Avenue Columbus OH, 43210-1174 Phone: 614-292-5256 Fax: 614 292-1479 Email: [email protected] 1 Abstract The ongoing activity of neurons generates a spatially- and time-varying field of extracellular voltage (Ve). This Ve field reflects population-level neural activity, but does it modulate neural dynamics and the function of neural circuits? We provide a cable theory framework to study how a bundle of model neurons generates Ve and how this Ve feeds back and influences membrane potential (Vm). We find that these “ephaptic interactions” are small but not negligible. The model neural population can generate Ve with millivolt-scale amplitude and this Ve perturbs the Vm of “nearby” cables and effectively increases their electrotonic length. After using passive cable theory to systematically study ephaptic coupling, we explore a test case: the medial superior olive (MSO) in the auditory brainstem. The MSO is a possible locus of ephaptic interactions: sounds evoke large Ve in vivo in this nucleus (millivolt-scale).