Arxiv:1708.00534V1 [Q-Bio.NC] 1 Aug 2017 Myelin and Saltatory Conduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary - Cellbiology

1 Glossary - Cellbiology Blotting: (Blot Analysis) Widely used biochemical technique for detecting the presence of specific macromolecules (proteins, mRNAs, or DNA sequences) in a mixture. A sample first is separated on an agarose or polyacrylamide gel usually under denaturing conditions; the separated components are transferred (blotting) to a nitrocellulose sheet, which is exposed to a radiolabeled molecule that specifically binds to the macromolecule of interest, and then subjected to autoradiography. Northern B.: mRNAs are detected with a complementary DNA; Southern B.: DNA restriction fragments are detected with complementary nucleotide sequences; Western B.: Proteins are detected by specific antibodies. Cell: The fundamental unit of living organisms. Cells are bounded by a lipid-containing plasma membrane, containing the central nucleus, and the cytoplasm. Cells are generally capable of independent reproduction. More complex cells like Eukaryotes have various compartments (organelles) where special tasks essential for the survival of the cell take place. Cytoplasm: Viscous contents of a cell that are contained within the plasma membrane but, in eukaryotic cells, outside the nucleus. The part of the cytoplasm not contained in any organelle is called the Cytosol. Cytoskeleton: (Gk. ) Three dimensional network of fibrous elements, allowing precisely regulated movements of cell parts, transport organelles, and help to maintain a cell’s shape. • Actin filament: (Microfilaments) Ubiquitous eukaryotic cytoskeletal proteins (one end is attached to the cell-cortex) of two “twisted“ actin monomers; are important in the structural support and movement of cells. Each actin filament (F-actin) consists of two strands of globular subunits (G-Actin) wrapped around each other to form a polarized unit (high ionic cytoplasm lead to the formation of AF, whereas low ion-concentration disassembles AF). -

Interplay Between Gating and Block of Ligand-Gated Ion Channels

brain sciences Review Interplay between Gating and Block of Ligand-Gated Ion Channels Matthew B. Phillips 1,2, Aparna Nigam 1 and Jon W. Johnson 1,2,* 1 Department of Neuroscience, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15260, USA; [email protected] (M.B.P.); [email protected] (A.N.) 2 Center for Neuroscience, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15260, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-(412)-624-4295 Received: 27 October 2020; Accepted: 26 November 2020; Published: 1 December 2020 Abstract: Drugs that inhibit ion channel function by binding in the channel and preventing current flow, known as channel blockers, can be used as powerful tools for analysis of channel properties. Channel blockers are used to probe both the sophisticated structure and basic biophysical properties of ion channels. Gating, the mechanism that controls the opening and closing of ion channels, can be profoundly influenced by channel blocking drugs. Channel block and gating are reciprocally connected; gating controls access of channel blockers to their binding sites, and channel-blocking drugs can have profound and diverse effects on the rates of gating transitions and on the stability of channel open and closed states. This review synthesizes knowledge of the inherent intertwining of block and gating of excitatory ligand-gated ion channels, with a focus on the utility of channel blockers as analytic probes of ionotropic glutamate receptor channel function. Keywords: ligand-gated ion channel; channel block; channel gating; nicotinic acetylcholine receptor; ionotropic glutamate receptor; AMPA receptor; kainate receptor; NMDA receptor 1. Introduction Neuronal information processing depends on the distribution and properties of the ion channels found in neuronal membranes. -

Thenerveimpulse05.Pdf

The nerve impulse. INTRODUCTION Axons are responsible for the transmission of information between different points of the nervous system and their function is analogous to the wires that connect different points in an electric circuit. However, this analogy cannot be pushed very far. In an electrical circuit the wire maintains both ends at the same electrical potential when it is a perfect conductor or it allows the passage of an electron current when it has electrical resistance. As we will see in these lectures, the axon, as it is part of a cell, separates its internal medium from the external medium with the plasma membrane and the signal conducted along the axon is a transient potential difference1 that appears across this membrane. This potential difference, or membrane potential, is the result of ionic gradients due to ionic concentration differences across the membrane and it is modified by ionic flow that produces ionic currents perpendicular to the membrane. These ionic currents give rise in turn to longitudinal currents closing local ionic current circuits that allow the regeneration of the membrane potential changes in a different region of the axon. This process is a true propagation instead of the conduction phenomenon occurring in wires. To understand this propagation we will study the electrical properties of axons, which include a description of the electrical properties of the membrane and how this membrane works in the cylindrical geometry of the axon. Much of our understanding of the ionic mechanisms responsible for the initiation and propagation of the action potential (AP) comes from studies on the squid giant axon by A. -

Spatial Extent of Neurons: Dendrites and Axons

Spatial extent of neurons: dendrites and axons Morphological diversity of neurons Cortical pyramidal cell Purkinje cell Retinal ganglion cells Motoneurons Dendrites: spiny vs non-spiny Recording and simulating dendrites Axons - myelinated vs unmyelinated Axons - myelinated vs unmyelinated • Myelinated axons: – Long-range axonal projections (motoneurons, long-range cortico-cortical connections in white matter, etc) – Saltatory conduction; – Fast propagation (10s of m/s) • Unmyelinated axons: – Most local axonal projections – Continuous conduction – Slower propagation (a few m/s) Recording from axons Recording from axons Recording from axons - where is the spike generated? Modeling neuronal processes as electrical cables • Axial current flowing along a neuronal cable due to voltage gradient: V (x + ∆x; t) − V (x; t) = −Ilong(x; t)RL ∆x = −I (x; t) r long πa2 L where – RL: total resistance of a cable of length ∆x and radius a; – rL: specific intracellular resistivity • ∆x ! 0: πa2 @V Ilong(x; t) = − (x; t) rL @x The cable equation • Current balance in a cylinder of width ∆x and radius a • Axial currents leaving/flowing into the cylinder πa2 @V @V Ilong(x + ∆x; t) − Ilong(x; t) = − (x + ∆x; t) − (x; t) rL @x @x • Ionic current(s) flowing into/out of the cell 2πa∆xIion(x; t) • Capacitive current @V I (x; t) = 2πa∆xc cap M @t • Kirschoff law Ilong(x + ∆x; t) − Ilong(x; t) + 2πa∆xIion(x; t) + Icap(x; t) = 0 • In the ∆x ! 0 limit: @V a @2V cM = 2 − Iion @t 2rL @x Compartmental appoach Compartmental approach Modeling passive dendrites: Cable equation -

Structure and Function Relationship in Nerve Cells & Membrane Potential

Structure and Function Relationship in Nerve Cells & Membrane Potential Asist. Prof. Aslı AYKAÇ NEU Faculty of Medicine Biophysics Nervous System Cells • Glia – Not specialized for information transfer – Support neurons • Neurons (Nerve Cells) – Receive, process, and transmit information Neurons • Neuron Doctrine – The neuron is the functional unit of the nervous system • Specialized cell type – have very diverse in structure and function Neuron: Structure/Function • designed to receive, process, and transmit information – Dendrites: receive information from other neurons – Soma: “cell body,” contains necessary cellular machinery, signals integrated prior to axon hillock – Axon: transmits information to other cells (neurons, muscles, glands) • Information travels in one direction – Dendrite → soma → axon How do neurons work? • Function – Receive, process, and transmit information – Conduct unidirectional information transfer • Signals – Chemical – Electrical Membrane Potential Because of motion of positive and negative ions in the body, electric current generated by living tissues. What are these electrical signals? • receptor potentials • synaptic potentials • action potentials Why are these electrical signals important? These signals are all produced by temporary changes in the current flow into and out of cell that drives the electrical potential across the cell membrane away from its resting value. The resting membrane potential The electrical membrane potential across the membrane in the absence of signaling activity. Two type of ions channels in the membrane – Non gated channels: always open, important in maintaining the resting membrane potential – Gated channels: open/close (when the membrane is at rest, most gated channels are closed) Learning Objectives • How transient electrical signals are generated • Discuss how the nongated ion channels establish the resting potential. -

Effect of Hyperkalemia on Membrane Potential: Depolarization

❖ CASE 3 A 6-year-old boy is brought to the family physician after his parents noticed that he had difficulty moving his arms and legs after a soccer game. About 10 minutes after leaving the field, the boy became so weak that he could not stand for about 30 minutes. Questioning revealed that he had complained of weakness after eating bananas, had frequent muscle spasms, and occasionally had myotonia, which was expressed as difficulty in releasing his grip or diffi- culty opening his eyes after squinting into the sun. After a thorough physical examination, the boy was diagnosed with hyperkalemic periodic paralysis. The family was advised to feed the boy carbohydrate-rich, low-potassium foods, give him glucose-containing drinks during attacks, and have him avoid strenuous exercise and fasting. ◆ What is the effect of hyperkalemia on cell membrane potential? ◆ What is responsible for the repolarizing phase of an action potential? ◆ What is the effect of prolonged depolarization on the skeletal muscle Na+ channel? 32 CASE FILES: PHYSIOLOGY ANSWERS TO CASE 3: ACTION POTENTIAL Summary: A 6-year-old boy who experiences profound weakness after exer- cise is diagnosed with hyperkalemic periodic paralysis. ◆ Effect of hyperkalemia on membrane potential: Depolarization. ◆ Repolarization mechanisms: Activation of voltage-gated K+ conductance and inactivation of Na+ conductance. ◆ Effect of prolonged depolarization: Inactivation of Na+ channels. CLINICAL CORRELATION Hyperkalemic periodic paralysis (HyperPP) is a dominant inherited trait caused by a mutation in the α subunit of the skeletal muscle Na+ channel. It occurs in approximately 1 in 100,000 people and is more common and more severe in males. -

Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Signaling in Neuroprotection

Akinori Akaike · Shun Shimohama Yoshimi Misu Editors Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Signaling in Neuroprotection Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Signaling in Neuroprotection Akinori Akaike • Shun Shimohama Yoshimi Misu Editors Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Signaling in Neuroprotection Editors Akinori Akaike Shun Shimohama Department of Pharmacology, Graduate Department of Neurology, School of School of Pharmaceutical Sciences Medicine Kyoto University Sapporo Medical University Kyoto, Japan Sapporo, Hokkaido, Japan Wakayama Medical University Wakayama, Japan Yoshimi Misu Graduate School of Medicine Yokohama City University Yokohama, Kanagawa, Japan ISBN 978-981-10-8487-4 ISBN 978-981-10-8488-1 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-8488-1 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018936753 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2018. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the book’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. -

Information Processing in the Axon Dominique Debanne

Information processing in the axon Dominique Debanne To cite this version: Dominique Debanne. Information processing in the axon. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, Nature Publishing Group, 2004, 5 (4), pp.304-316. 10.1038/nrn1397. hal-01766862 HAL Id: hal-01766862 https://hal-amu.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01766862 Submitted on 27 Aug 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. INFORMATION PROCESSING IN THE AXON Dominique Debanne Axons link distant brain regions and are generally regarded as reliable transmission cables in which stable propagation occurs once an action potential has been generated. However, recent experimental and theoretical data indicate that the functional capabilities of axons are much more diverse than traditionally thought. Beyond axonal propagation, intrinsic voltage-gated conductances together with the intrinsic geometrical properties of the axon determine complex phenomena such as branch-point failures and reflected propagation. This review considers recent evidence for the role of these forms of axonal computation in the short-term dynamics of neural communication. GAP JUNCTIONS Since the pioneering work of Santiago Ramón y Cajal, of propagation and how intrinsic channels that are Morphological equivalent of the axon has been defined as a long neuronal process present in the axon shape the action potential. -

9.01 Introduction to Neuroscience Fall 2007

MIT OpenCourseWare http://ocw.mit.edu 9.01 Introduction to Neuroscience Fall 2007 For information about citing these materials or our Terms of Use, visit: http://ocw.mit.edu/terms. 9.01 Recitation (R02) RECITATION #2: Tuesday, September 18th Review of Lectures: 3, 4 Reading: Chapters 3, 4 or Neuroscience: Exploring the Brain (3rd edition) Outline of Recitation: I. Previous Recitation: a. Questions on practice exam questions from last recitation? II. Review of Material: a. Exploiting Axoplasmic Transport b. Types of Glia c. THE RESTING MEMBRANE POTENTIAL d. THE ACTION POTENTIAL III. Practice Exam Questions IV. Questions on Pset? Exploiting Axoplasmic Transport: Maps connections of the brain Rates of transport: - slow: - fast: Examples: Uses anterograde transport: - Uses retrograde transport: - - - Types of Glia: - Microglia: - Astrocytes: - Myelinating Glia: 1 THE RESTING MEMBRANE POTENTIAL: The Cast of Chemicals: The Movement of Ions: Influences by two factors: (1) Diffusion: (2) Electricity: Ohm’s Law: I = gV Ionic Equilibrium Potentials (EION): + Example: ENs * diffusional and electrical forces are equal 2 Nernst Equation: EION = 2.303 RT/zF log [ion]0/[ion]i Calculates equilibrium potential for a SINGLE ion. Inside Outside EION (at 37°C) + [K ] + [Na ] 2+ [Ca ] [Cl ] *Pumps maintain concentration gradients (ex. sodiumpotassium pump; calcium pump) Resting Membrane Potential (VM at rest): Measured resting membrane potential: 65 mV Goldman Equation: + + + + VM = 61.54 mV log (PK[K ]o + PNa[Na ]o)/ (PK[K ]I + PNa[Na ]i) + + Calculates membrane potential when permeable to both Na and K . Remember: at REST, gK >>> gNa therefore, VM is closer to EK THE ACTION POTENTIAL (Nerve Impulse): Phases of an Action Potential: Vm (mV) ENa 0 EK Time 3 Conductance of Ion Channels during AP: Remember: Changes in conductance, or permeability of the membrane to a specific ion, changes the membrane potential. -

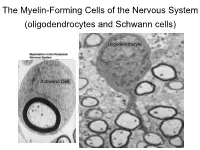

The Myelin-Forming Cells of the Nervous System (Oligodendrocytes and Schwann Cells)

The Myelin-Forming Cells of the Nervous System (oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells) Oligodendrocyte Schwann Cell Oligodendrocyte function Saltatory (jumping) nerve conduction Oligodendroglia PMD PMD Saltatory (jumping) nerve conduction Investigating the Myelinogenic Potential of Individual Oligodendrocytes In Vivo Sparse Labeling of Oligodendrocytes CNPase-GFP Variegated expression under the MBP-enhancer Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Ant Commissure Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Piriform Cortex Corpus Callosum Ant Commissure Characterization of Oligodendrocyte Morphology Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Caudate Putamen Cerebellum Brain Stem Spinal Cord Oligodendrocytes in disease: Cerebral Palsy ! CP major cause of chronic neurological morbidity and mortality in children ! CP incidence now about 3/1000 live births compared to 1/1000 in 1980 when we started intervening for ELBW ! Of all ELBW {gestation 6 mo, Wt. 0.5kg} , 10-15% develop CP ! Prematurely born children prone to white matter injury {WMI}, principle reason for the increase in incidence of CP ! ! 12 Cerebral Palsy Spectrum of white matter injury ! ! Macro Cystic Micro Cystic Gliotic Khwaja and Volpe 2009 13 Rationale for Repair/Remyelination in Multiple Sclerosis Oligodendrocyte specification oligodendrocytes specified from the pMN after MNs - a ventral source of oligodendrocytes -

1365.Full.Pdf

The Journal of Neuroscience May 1966, 6(5): 1365-1371 Analysis of the Carbohydrate Composition of Axonally Transported Glycoconjugates in Sciatic Nerve Clyde E. Hart and John G. Wood Department of Anatomy, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia 30322 Glycosidase enzyme digestion in combination with postembed- schlag and Stone, 1982, for reviews). Therefore, the ability to ding lectin cytochemistry was used to study the carbohydrate characterize in situ the carbohydrate compositionof lectin bind- composition of axonally transported glycoproteins. A cold block ing sites of intracellular membranecompartments and on the procedure for the interruption of axonal transport was employed cell surface may further our understandingof the site(s) of gly- to increase selectively the population of anterograde moving coprotein oligosaccharideprocessing in neurons. components on the proximal side of the transport block. Elec- tron-microscopic observations revealed that a cold block applied In this study we have used a modification of the cold block to the sciatic nerve of an anesthetized rat produced an increase technique of Hanson (1978) to interrupt axonal transport in the in axonal smooth membrane vesicles at a site directly proximal sciatic nerve of rats in order to increase the content of antero- to the cold block. Postembedding lectin cytochemistry of the gradely transported glycoproteins at a focal point along the nerve. sciatic nerve demonstrated a substantial increase in concanav- Results of postembedding lectin cytochemistry and endo- and alin A (Con A), wheat germ agglutinin (WGA), and succinylat- exo-glycosidase digestions of the cold-blocked sciatic nerve in- ed WGA binding sites in axons directly proximal to the cold dicated that some of the axonally transported glycoprotein car- block. -

Gathering at the Nodes

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS GLIA Gathering at the nodes Saltatory conduction — the process by which that are found at the nodes of Ranvier, where action potentials propagate along myelinated they interact with Na+ channels. When the nerves — depends on the fact that voltage- authors either disrupted the localization of gated Na+ channels form clusters at the nodes gliomedin by using a soluble fusion protein of Ranvier, between sections of the myelin that contained the extracellular domain of sheath. New findings from Eshed et al. show neurofascin, or used RNA interference to that Schwann cells produce a protein called suppress the expression of gliomedin, the gliomedin, and that this is responsible for characteristic clustering of Na+ channels at the clustering of these channels. the nodes of Ranvier did not occur. The formation of the nodes of Ranvier is Aggregation of the domain of gliomedin specified by the myelinating cells, not the that binds neurofascin and NrCAM on the axons, and an important component of this surface of purified neurons also caused process in the peripheral nervous system the clustering of neurofascin, Na+ channels is the extension of microvilli by Schwann and other nodal proteins. These findings cells. These microvilli contact the axons at support a model in which gliomedin on the nodes, and it is here that the Schwann References and links Schwann cell microvilli binds to neurofascin ORIGINAL RESEARCH PAPER Eshed, Y. et al. Gliomedin cells express the newly discovered protein and NrCAM on axons, causing them to mediates Schwann cell–axon interaction and the molecular gliomedin. cluster at the nodes of Ranvier, and leading assembly of the nodes of Ranvier.