Secrets of Metaethics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

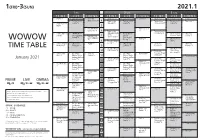

7(Thu) 2021.1

24(###)-27(###) 2021.1 1(FRI)-3(SUN) 2021.1 24 SUN. 25 MON. 26 TUE. 27 WED. 1 FRI. 2 SAT. 3 SUN. PRIME LIVE CINEMA PRIME LIVE CINEMA PRIME LIVE CINEMA PRIME LIVE CINEMA PRIME LIVE CINEMA PRIME LIVE CINEMA PRIME LIVE CINEMA 2:05 Siberia(2018)*1 2:15 La Liga 20-21 Season*2 2:50 Beruseruku Ougon Jidai Hen 2:15 La Liga 20-21 Season*2 2:30 Tokyo Jihen 00 The Big Shot 2:00 Eternal Love of 2:40 La Liga 20-21 Season*2 3:00 The Vow from Hiroshima*1 15 Eiga Kobo*5 25 Songland*5 3:15 K-20 Kaijin 20 3:00 X-Men*1 2:45 La Liga 20-21 Season*2 15 Enter the 0:00 MOZU Season 1...*4 2:45 La Liga 20-21 Season*2 3:45 Creed II*1 0:00 MOZU Season 1...*4 2:15 La Liga 20-21 Season*2 20 Hanbun no Sekai*1 45 La Liga 20-21 50 Ford v Ferrari*1 45 La Liga 20-21 2020.7.24 Uruu (2019)*1 4 Dream*4 45 Tenisugurandosuramu 30 Little Monsters 35 Inside Man*1 Menso Den*1 58 La Liga 20-21 Dragon(1973)*1 4 55 Night at the 45 La Liga 20-21 30 Spider-Man: 45 La Liga 20-21 45 Han Ochi*1 Season*2 Season*2 vision Tokuban Mei Shobu Sen*2 (2018)*1 Season*2 Museum*1 Season*2 Homecoming*1 Season*2 News Flash*3 20 Level Up*1 15 CONTACT ART ~ Harada 00 X-Men United 5 50 ~~~ ~ Kyukyoku 45 Don't Sleep*1 (X2)*1 5 00 The 15 The Great Kakutougi ~ UFC 00 Parallel World 00 Kumo no Su Jo 257*2 Flintstones*1 6 45 Kimu~ Namuju× War*1 45 Kimu~ Namuju× Love Story*1 6 45 Night at the *1 45 Spider-Man: Far 05 CONTACT ART ~ Harada 25 Shuto 05 Kimu~ Namuju× Chi~jini~ Chi~jini~ Misutei Chi~jini~ Misutei 15 X-Men: The Last 00 UEFA EUROTM Museum: Battle 05 Excite Match from Home*1 05 Hajimete no Danshi 00 -

Rassegna INDICE RASSEGNA STAMPA Rassegna

rassegna INDICE RASSEGNA STAMPA rassegna Si parla di noi Repubblica Firenze 14/10/2017 p. XIV Searching for X Japan Il nostro drammma rock" Fulvio Paloscia 1 Tirreno 14/10/2017 p. 23 Il cult X Japan stasera al Festival dei Popoli 3 Corriere Fiorentino 14/10/2017 p. 14 GIAPPONE ROCK 4 D - La Repubblica 14/10/2017 p. 14 BIG IN JAPAN 5 Delle Donne Si gira in Toscana Bisenzio 7 13/10/2017 p. 44 Girata l'ultima scena del diavolo di Rimondeto 6 Indice Rassegna Stampa Pagina I Festival dei PopoliAlla Compagnia Yoshiki, il leader della band giapponese e il film su una storia di successi e ferite (stasera) SearchingforXJapan nostro (1ranmiaroc Si parla di noi Pagina 1 FULVIO PALOSCIA arretrato quando si parla di rock». prattutto il ritratto di Yoshiki, della fra- IL DOCUMENTARIO Si conoscono e formano la band appe- gilità fisica e psicologica che si porta Alcune scene di "We OSHIKi deve essere grato a na quindicenni. A 20 anni la Sony li dietro fin da quando, da bambino, assi- are >("che racconta Stephen Kijiak, il regista mette sotto contratto. Con il loro abbi- ste al suicidio del padre, gesto che ha la storia degli X del documentario We are X gliamento che rilegge il glam con spiri- cercato più volte di ripercorrere lui stes- Japan, la più grande che racconta tutta, ma pro- to manga e che scavalcai generi sessua- so: «Un nostro produttore dice che, sin rock band del prio tutta la storia degliX Ja- li, con i loro capelli punk e le loro canzo- da ragazzo, emanavo un senso di mor- Giappone. -

The Apology | the B-Side | Night School | Madonna: Rebel Heart Tour | Betting on Zero Scene & Heard

November-December 2017 VOL. 32 THE VIDEO REVIEW MAGAZINE FOR LIBRARIES N O . 6 IN THIS ISSUE One Week and a Day | Poverty, Inc. | The Apology | The B-Side | Night School | Madonna: Rebel Heart Tour | Betting on Zero scene & heard BAKER & TAYLOR’S SPECIALIZED A/V TEAM OFFERS ALL THE PRODUCTS, SERVICES AND EXPERTISE TO FULFILL YOUR LIBRARY PATRONS’ NEEDS. Learn more about Baker & Taylor’s Scene & Heard team: ELITE Helpful personnel focused exclusively on A/V products and customized services to meet continued patron demand PROFICIENT Qualified entertainment content buyers ensure frontlist and backlist titles are available and delivered on time SKILLED Supportive Sales Representatives with an average of 15 years industry experience DEVOTED Nationwide team of A/V processing staff ready to prepare your movie and music products to your shelf-ready specifications Experience KNOWLEDGEABLE Baker & Taylor is the Full-time staff of A/V catalogers, most experienced in the backed by their MLS degree and more than 43 years of media cataloging business; selling A/V expertise products to libraries since 1986. 800-775-2600 x2050 [email protected] www.baker-taylor.com Spotlight Review One Week and a Day and target houses that are likely to be empty while mourners are out. Eyal also goes to the HHH1/2 hospice where Ronnie died (and retrieves his Oscilloscope, 98 min., in Hebrew w/English son’s medical marijuana, prompting a later subtitles, not rated, DVD: scene in which he struggles to roll a joint for Publisher/Editor: Randy Pitman $34.99, Blu-ray: $39.99 the first time in his life), gets into a conflict Associate Editor: Jazza Williams-Wood Wr i t e r- d i r e c t o r with a taxi driver, and tries (unsuccessfully) to hide in the bushes when his neighbors show Editorial Assistant: Christopher Pitman Asaph Polonsky’s One Week and a Day is a up with a salad. -

1(Tue)-3(Thu) 2018.5

24(THU)-27(SUN) 2018.5 1(TUE)-3(THU) 2018.5 24 THU. 25 FRI. 26 SAT. 27 SUN. 1 TUE. 2 WED. 3 THU. PRIME LIVE CINEMA PRIME LIVE CINEMA PRIME LIVE CINEMA PRIME LIVE CINEMA PRIME LIVE CINEMA PRIME LIVE CINEMA PRIME LIVE CINEMA 00 Fantastic Beasts 2:00 NBA Basketball 3:00 Yoshida Rui...*1 00 Passengers 2:00 NBA Basketball 00 Kaze Tachinu 3:30 Rugby French 2:00 NBA Basketball 1:45 Tsuioku(2017)*1 2:00 NBA Basketball 00 Women's Golf 3:00 Pirates of the 2:30 Shizumanu 3:20 Liga Espanola 00 X-Men: 1:00 Shizumanu 2:00 NBA Basketball 00 The Conjuring 2 1:20 Shizumanu 2:30 Liga Espanola...*2 2:45 Source Code*1 and Where to 17-18 Season 30 Shunkinsho (2016)*1 17-18 Season (1976)*1 4 League TOP 14 17-18 Season 30 Terms of 17-18 Season LPGA Tour Caribbean :Dead Taiyo*4 17-18 Season*2 Apocalypse*1 4 Taiyo*4 17-18 Season*2 *1 Taiyo*4 30 Endeavour*4 30 Moon(2009)*1 Find Them*1 Playoffs Final*2 Playoffs Final*2 17-18 Season Playoffs Final*2 Playoffs Final*2 2018 Michigan Man's Chest*1 (1976)*1 Endearment*1 10 Nonfiction W*5 00 The Bleeder Playoffs LPGA Volvik 5 5 (Chuck)*1 30 2.5 Jigen Danshi 30 MUCC 45 Fai bei sogni*1 Semifinals 45 Yogaku BREAK*3 30 Storks*1 Championship 45 Pirates of the 15 Hayaoki Oshi TV*5 10 La vita possibile 15 Hayaoki 20 Shunen (Live Coverage) 00 Excite Match Day-3 Caribbean: At 15 Hayaoki Rakugo 00 Liga Espanola 15 Hayaoki Rakugo 15 Hollywood Kinen LIVE World's End*1 Rakugo*5 *1 Rakugo*5 6 *2 World 45 Eiga Kobo*5 (Live Coverage) *5 17-18 Season 6 *5 45 Women's Golf 30 Salt(2010)*1 45 Eiga Kobo*5 Express*5 Nippon Professional *2 Real -

The Sermons of Edwin Sandys

S E R M N S MISCELLANEOUS PIECES ARCHBISHOP SANDYS. Cfjc ^arfter *<metg. SnetituteD a.H. i*l. ©<£<£<£. Sit. jFor ttje ^uolication of tfj* ffiftlorfee of tfjc ^Fatfjere anD (fParlp ftgUritcre of tlje Urformrn THE SERMONS EDWIN SANDYS, D- D., SUCCESSIVELY BISHOP OF WORCESTER AND LONDON, AND ARCHBISHOP OF YORK; TO WHICH ARI ADDED SOME MISCELLANEOUS PIECES, THE SAME AUTHOR. EDITED FOR BY THE REV. JOHN AYRE, M.A., MINISTER OF ST JOHN'S CHAPEL, HAMPSTEAP. CAMBRIDGE: PRINTED AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS. M.DCCC.XLII. ( ONT K N T S. Biographical Notice of Archbishop Sandys i Epistle to the Reader i Order and Matter of the Sermons 5 Sermons 7 MISCELLANEOUS PIECES. Advice concerning Rites and Ceremonies in the Synod I5fi2 438 Orders for the Bishops and Clergy 434 Advertisement to the translation of Luther's Commentary on Galatians 435 Epistola Pastoralis Episcopo Cestrensi 43'! The same translated 430 Prayers to be used at Hawkshead School 443 Preamble to the Archbishop's will 440 Notes 453 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTICE ARCHBISHOP SANDYS. Edwin Sandys or Sandes was born in the year 1519, near Havvkshead, in the part of Lancashire called Furness Fells. He was the third son of William Sandys, Esq. and Margaret his wife, a descendant of the ancient barons of Kendal. As Easthwaite Hall was the principal resi- dence of the father, it is probable that it was in this house that Edwin first saw the light. It is not certainly known at what seminary the future archbishop received the rudiments of his education : it has however been conjectured with some plausibility by a bio- grapher that, as the school of Furness Abbey was then highly distinguished, and as his family were feudatories of that house, he was a pupil of the monks. -

Following Is a Listing of Public Relations Firms Who Have Represented Films at Previous Sundance Film Festivals

Following is a listing of public relations firms who have represented films at previous Sundance Film Festivals. This is just a sample of the firms that can help promote your film and is a good guide to start your search for representation. 11th Street Lot 11th Street Lot Marketing & PR offers strategic marketing and publicity services to independent films at every stage of release, from festival premiere to digital distribution, including traditional publicity (film reviews, regional and trade coverage, interviews and features); digital marketing (social media, email marketing, etc); and creative, custom audience-building initiatives. Contact: Lisa Trifone P: 646.926-4012 E: [email protected] www.11thstreetlot.com 42West 42West is a US entertainment public relations and consulting firm. A full service bi-coastal agency, 42West handles film release campaigns, awards campaigns, online marketing and publicity, strategic communications, personal publicity, and integrated promotions and marketing. With a presence at Sundance, Cannes, Toronto, Venice, Tribeca, SXSW, New York and Los Angeles film festivals, 42West plays a key role in supporting the sales of acquisition titles as well as launching a film through a festival publicity campaign. Past Sundance Films the company has represented include Joanna Hogg’s THE SOUVENIR (winner of World Cinema Grand Jury Prize: Dramatic), Lee Cronin’s THE HOLE IN THE GROUND, Paul Dano’s WILDLIFE, Sara Colangelo’s THE KINDERGARTEN TEACHER (winner of Director in U.S. competition), Maggie Bett’s NOVITIATE -

FEATURE DOCUMENTARY Catalogue

FEATURE DOCUMENTARY Catalogue ACTIVE MEASURES Active Measures chronicles the most successful espionage operation in Russian history, the American presidential election of 2016. Filmmaker Jack Bryan exposes a 30-year history of covert political warfare devised by Vladimir Putin to disrupt, and ultimately control world events. Running time: 1 x 109-minutes Produced by: Shooting Films Year of production: 2017 -2018 THE ALEXANDER COMPLEX (w/t) The words ‘tomb of Alexander’ draw one of the world’s foremost archaeologists and a team of experts, on 6 expeditions to uncover the truth. The stakes are high in this breathtaking game of strategy as they face fatwas, military interventions and the stoic bedrock of the ancient Middle-East. One man, code- named ‘The Inventor’ holds the exact coordinates of the tomb entrance – will he give up the secret? Running time: 1 x 90-minutes Produced by: Soilsiú Films & Fine Point Films production Year of production: 2019 ALIAS RUBY BLADE Kirsty Sword, a young Australian activist, aspired to be a documentary filmmaker in East Timor, but instead became an underground operative for the Timorese resistance against Indonesia in Jakarta. Her code name: Ruby Blade. Her task: to become a conduit for information and instruction between the resistance movement and its enigmatic leader, Kay Rala “Xanana” Gusmão, while he was serving a life sentence in prison for his revolutionary activities. Through correspondence, they fell in love. Alias Ruby Blade captures their incredible love story from its beginning to the ultimate triumph of freedom in East Timor, demonstrating the astonishing power of ordinary individuals to change the course of history. -

1. UK Films for Sale TIFF 2016

Prepared by Although great efforts have been made to present correct and up-to-date details, no warranty is made regarding the accuracy or completeness of the information in this listing. Films have been included because they match several criteria, including: Where completed, films are less than one year old (not seen at or before AFM 2015). They are represented in person by a contactable sales company at AFM in 2016. 47 Meters Down TAltitude Film Sales Cast: Claire Holt, Mandy Moore , Matthew Modine Robin Andrews +44 796 842 8658 Genre: Thriller [email protected] Director: Johannes Roberts Market Office: Loews #863 Status: Completed Home Office tel: +44 20 7478 7612 Synopsis: Twenty-something sisters Kate and Lisa are gorgeous, fun-loving and ready for the holiday of a lifetime in Mexico. When the opportunity to go cage diving to view Great White sharks presents itself, thrill-seeking Kate jumps at the chance while Lisa takes some convincing. After some not so gentle persuading, Lisa finally agrees and the girls soon find themselves two hours off the coast of Huatulco and about to come face to face with nature's fiercest predator. But what should have been the trip to end all trips soon becomes a living nightmare when the shark cage breaks free from their boat, sinks and they find themselves trapped at the bottom of the ocean. With less than an hour of oxygen left in their tanks, they must somehow work out how to get back to the boat above them through 47 meters of shark-infested waters. -

X Japan We Are X Mp3, Flac, Wma

X Japan We Are X mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Stage & Screen Album: We Are X Country: US Released: 2017 MP3 version RAR size: 1484 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1745 mb WMA version RAR size: 1559 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 426 Other Formats: DTS AIFF AHX RA WAV VQF ADX Tracklist We Are X Movie 1 We Are X Bonus 2 Yoshiki On We Are X 3 Last Live : Forever Love 4 Last Live : Kurenai 5 Deleted Scene : Yuko Yamaguchi And Yoshikitty 6 Deleted Scene : Hello Kitty Con 7 Deleted Scene : New Economy Summit 8 Deleted Scene : Tateyama 9 Deleted Scene : X Museum 10 Interview : Yoshiki 11 Interview : Toshi 12 Interview : Pata 13 Interview : Heath 14 Interview : Sugizo 15 Fan Video : Born To Be Free Companies, etc. Copyright (c) – XJ Films LLC Copyright (c) – Magnolia Home Entertainment Credits Bass – Heath , Taiji Cinematographer – John Maringouin, Stephen Kijak Drums, Piano – Yoshiki Edited By – John Maringouin, Mako Kamisuna Film Director – Stephen Kijak Film Producer – Diane Becker Guitar – Hide , Pata, Sugizo Producer – John Battsek Vocals – Toshi Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode (Scanned): 876964011563 Barcode (Printed): 8 76964 01156 3 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year 11155 X Japan We Are X (DVD, NTSC) Magnet 11155 US 2017 We Are X (Blu-ray + DVD France & none X Japan Eurozoom none 2018 + CD, Comp) Benelux We Are X (3xBlu-ray, TBR27346D X Japan Toho Records TBR27346D Japan 2017 S/Edition) We Are X (Blu-ray, Ltd, none X Japan The Blu none South Korea 2017 Red + CD, Album, Comp) Manga -

To Walk Invisible: the Brontë Sisters | All Governments Lie | the Great War | Strike a Pose | Keep Quiet | Rachel Carson Scene & Heard

July-August 2017 VOL. 32 THE VIDEO REVIEW MAGAZINE FOR LIBRARIES N O . 4 IN THIS ISSUE To Walk Invisible: The Brontë Sisters | All Governments Lie | The Great War | Strike A Pose | Keep Quiet | Rachel Carson scene & heard BAKER & TAYLOR’S SPECIALIZED A/V TEAM OFFERS ALL THE PRODUCTS, SERVICES AND EXPERTISE TO FULFILL YOUR LIBRARY PATRONS’ NEEDS. Learn more about Baker & Taylor’s Scene & Heard team: Experience Baker & Taylor is the ELITE most experienced in the Helpful personnel focused exclusively on A/V products and business; selling A/V customized services to meet continued patron demand products to libraries since 1986. PROFICIENT Qualified entertainment content buyers ensure frontlist and backlist titles are available and delivered on time SKILLED Supportive Sales Representatives with an average of 15 years industry experience DEVOTED Nationwide team of A/V processing staff ready to prepare your movie and music products to your shelf-ready specifications KNOWLEDGEABLE Full-time staff of A/V catalogers, backed by their MLS degree and more than 43 years of media cataloging expertise 800-775-2600 x2050 [email protected] www.baker-taylor.com Spotlight Review To Walk Invisible: and the delicate reticence of Anne (Charlie Murphy)—while also portraying Branwell The Brontë Sisters (Adam Nagaitis) and their father Patrick HHHH (Jonathan Pryce) with a touching degree of PBS, 120 min., not rated, sympathy, given the obvious flaws of both Publisher/Editor: Randy Pitman DVD: $29.99, Blu-ray: $34.99 men. In addition to the drama surrounding Associate Editor: Jazza Williams-Wood Branwell’s troubles, the narrative explores The most significant Editorial Assistant: Christopher Pitman the almost comical difficulties that the period (1845-48) in the sisters confronted in trying to protect their Graphic Designer: Carol Kaufman lives of 19th-century “intellectual property” interests while also British authors Anne, Marketing Director: Anne Williams preserving their anonymity after their nov- Charlotte, and Emily els became wildly popular. -

TRANSCULTURAL SPACES in SUBCULTURE: an Examination of Multicultural Dynamics in the Japanese Visual Kei Movement

TRANSCULTURAL SPACES IN SUBCULTURE: An examination of multicultural dynamics in the Japanese visual kei movement Hayley Maxime Bhola 5615A031-9 January 10, 2017 A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate School of International Culture and Communication Studies Waseda University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts TRANSCULTURAL SPACES IN SUBCULTURE 2 Abstract of the Dissertation The purpose of this dissertation was to examine Japanese visual kei subculture through the theoretical lens of transculturation. Visual kei (ヴィジュアル系) is a music based subculture that formed in the late 1980’s in Japan with bands like X Japan, COLOR and Glay. Bands are recognized by their flamboyant (often androgynous appearances) as well as their theatrical per- formances. Transculturation is a term originally coined by ethnographer Fernando Ortiz in re- sponse to the cultural exchange that took place during the era of colonization in Cuba. It de- scribes the process of cultural exchange in a way that implies mutual action and a more even dis- tribution of power and control over the process itself. This thesis looked at transculturation as it relates to visual kei in two main parts. The first was expositional: looking at visual kei and the musicians that fall under the genre as a product of transculturation between Japanese and non- Japanese culture. The second part was an effort to label visual kei as a transcultural space that is able to continue the process of transculturation by fostering cultural exchange and development among members within the subculture in Japan. Chapter 1 gave a brief overview of the thesis and explains the motivation behind conduct- ing the research. -

Official Festival Program 2015

TABLE Of Contents • BIFF Mission Statement ..................................................................................................................................... 5 • Greetings from the Founder & Executive Director .......................................................................... 7 • Meet Our Sponsors ............................................................................................................................................ 9 • BIFF Jurors ................................................................................................................................................................ 11 • Spirit of Freedom Narrative & Documentary Jury ........................................................................ 13 • New Visions Jury ................................................................................................................................................. 15 • Short Film Jury ..................................................................................................................................................... 17 • Opening Night Film ........................................................................................................................................... 18 • Closing Night Film .............................................................................................................................................. 19 • Special Screenings ............................................................................................................................................