P. D. JAMES - the Lighthouse in Memory of My Husband Connor Bantry White 1920–1964 CONTENTS AUTHOR’S NOTE Prologue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Unsuitable Job for a Woman Free

FREE AN UNSUITABLE JOB FOR A WOMAN PDF P. D. James | 240 pages | 17 Jun 2015 | FABER & FABER | 9780571228553 | English | London, United Kingdom An Unsuitable Job for a Woman () - IMDb Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Handsome Cambridge dropout Mark Callender died hanging by the neck with a faint trace of lipstick on his mouth. When the official verdict is suicide, his wealthy father hires fledgling private investigator Cordelia Gray to find out what led him to self-destruction. What she discovers instead is a twisting trail of secrets and sins, and the strong scent of murder. Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. Published April 17th by Scribner first published More Details Original Title. Cordelia Gray 1. Adam DalglieshCordelia Gray. Edgar Award Nominee for Best Novel Other Editions Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about An Unsuitable Job for a Womanplease sign up. Both are temporary typists sent to assist a cop-turned-private detective and end up becoming partners at the agency. Both consider going back to typing when things don't seem to go their way as investigators' sidekicks. Lara I was struck by the similarity in style and tone to The Cuckoo's Calling. Not to take anything away from that book, I enjoyed it, but Rowling was clea …more I was struck by the similarity in style and tone to The Cuckoo's Calling. -

New Information from Hearings That Were

REQUESTS FOR DETERMINATION Greenberg/Morachnick 17 Pocomo Road Laurentide Environmental, LLC 14 South Shore Road Nantucket, MA 02554 e-mail: [email protected] (508) – 332 – 9722 Field Inspection Report Date: September 1, 2015 Applicant / Owner: Mark Greenberg & Tami Morachnick Location: 17 Pocomo Road Agent: Blackwell & Associates - Art Gasbarro Comments: Developed lot off Pocomo Road. Due to time constraints, I was unable to visit the property on 9/1. Will be able to inspect on 9/16. The project narrative has the limit of work at the 25-foot buffer and the proposed garage no closer than 50 feet to the wetland boundary. These setbacks have usually required the filing of a NOI. However, the submitted plans show the limit of work in excess of 50-feet to the wetland boundary and the proposed garage partially outside the 100-foot buffer. Questions and Recommendations: Clarify the wetland setbacks for the project. Wait for the results of the wetland boundary review on 9/16. Inspector: B. Perry CERTIFICATES OF COMPLIANCE Otto 4 Brant Point Road SE48-2712 Draft Minutes Proposed Minutes for September 2, 2015 CONSERVATION COMMISSION PUBLIC MEETING 2 Bathing Beach Road Nantucket, Massachusetts 02554 www.nantucket-ma.gov Wednesday, September 2, 2015 4:00 P.M. 4 Fairgrounds Road, Training Room Commissioners: Ernie Steinauer (Chair), Andrew Bennett (Vice Chair), Ashley Erisman, David LaFleur, Ben Champoux, Ian Golding, Joe Topham Called to order at 4:00 p.m. Staff in attendance: Jeff Carlson, Natural Resources Coordinator Attending Members: Steinauer, Bennett, Erisman, LaFleur, Champoux, Golding, Topham Absent Members: None Late Arrivals: None Earlier Departure: None Agenda adopted by unanimous consent *Matter has not been heard I. -

Historically Famous Lighthouses

HISTORICALLY FAMOUS LIGHTHOUSES CG-232 CONTENTS Foreword ALASKA Cape Sarichef Lighthouse, Unimak Island Cape Spencer Lighthouse Scotch Cap Lighthouse, Unimak Island CALIFORNIA Farallon Lighthouse Mile Rocks Lighthouse Pigeon Point Lighthouse St. George Reef Lighthouse Trinidad Head Lighthouse CONNECTICUT New London Harbor Lighthouse DELAWARE Cape Henlopen Lighthouse Fenwick Island Lighthouse FLORIDA American Shoal Lighthouse Cape Florida Lighthouse Cape San Blas Lighthouse GEORGIA Tybee Lighthouse, Tybee Island, Savannah River HAWAII Kilauea Point Lighthouse Makapuu Point Lighthouse. LOUISIANA Timbalier Lighthouse MAINE Boon Island Lighthouse Cape Elizabeth Lighthouse Dice Head Lighthouse Portland Head Lighthouse Saddleback Ledge Lighthouse MASSACHUSETTS Boston Lighthouse, Little Brewster Island Brant Point Lighthouse Buzzards Bay Lighthouse Cape Ann Lighthouse, Thatcher’s Island. Dumpling Rock Lighthouse, New Bedford Harbor Eastern Point Lighthouse Minots Ledge Lighthouse Nantucket (Great Point) Lighthouse Newburyport Harbor Lighthouse, Plum Island. Plymouth (Gurnet) Lighthouse MICHIGAN Little Sable Lighthouse Spectacle Reef Lighthouse Standard Rock Lighthouse, Lake Superior MINNESOTA Split Rock Lighthouse NEW HAMPSHIRE Isle of Shoals Lighthouse Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse NEW JERSEY Navesink Lighthouse Sandy Hook Lighthouse NEW YORK Crown Point Memorial, Lake Champlain Portland Harbor (Barcelona) Lighthouse, Lake Erie Race Rock Lighthouse NORTH CAROLINA Cape Fear Lighthouse "Bald Head Light’ Cape Hatteras Lighthouse Cape Lookout Lighthouse. Ocracoke Lighthouse.. OREGON Tillamook Rock Lighthouse... RHODE ISLAND Beavertail Lighthouse. Prudence Island Lighthouse SOUTH CAROLINA Charleston Lighthouse, Morris Island TEXAS Point Isabel Lighthouse VIRGINIA Cape Charles Lighthouse Cape Henry Lighthouse WASHINGTON Cape Flattery Lighthouse Foreword Under the supervision of the United States Coast Guard, there is only one manned lighthouses in the entire nation. There are hundreds of other lights of varied description that are operated automatically. -

DOOR COUNTY LIGHTHOUSE FESTIVALS Spring Festival: June 12, 13, 14 | Fall Festival: October 3 & 4

27TH ANNUAL DOOR COUNTY LIGHTHOUSE FESTIVALS Spring Festival: June 12, 13, 14 | Fall Festival: October 3 & 4 ORDER TICKETS: Online at doorcountytickets.com Or by Calling the Door County Maritime Museum at 920.743.5958 Photo by Daniel Anderson Photography. MEMBERS-ONLY PRESALE TICKETS BEGIN ON FEBRUARY 24TH TICKETS OPEN TO THE PUBLIC ON MARCH 23RD SPRING LIGHTHOUSE FESTIVAL – LOCATION HOURS: PARTICIPANT INFORMATION: Door County Maritime Museum – Sturgeon Bay*: 9am-5pm all weekend • Arrive at the tour departure location at least 15 minutes before departure time Death’s Door Maritime Museum – Gills Rock*: 10am-5pm all weekend • Dress in layers as the weather can change quickly Cana Island Lighthouse – Baileys Harbor*: 10am-5pm all weekend Sherwood Point Lighthouse – Sturgeon Bay: 10am-4pm (Saturday & Sunday) • Take note of the lunch details of each tour USCG Canal Station – Sturgeon Bay: 10am-4pm (Saturday & Sunday) • Bring your camera, sunscreen, and bug spray Eagle Bluff Lighthouse – Peninsula State Park*: 10am-4pm all weekend • Wear sturdy close-toed shoes, especially when hiking Pottawatomie Lighthouse – Rock Island: 10am-4pm all weekend • Each lighthouse tour ticket includes free admission to the Death’s Door Maritime Museum in Gills Rock through the Ridges Range Lights – Baileys Harbor*: 11am-2pm all weekend end of the 2020 season *Please note, if you are planning a self-guided experience, there may be an admission rate. Order Tickets Online at doorcountytickets.com 27TH ANNUAL DOOR COUNTY LIGHTHOUSE FESTIVALS 27TH ANNUAL DOOR COUNTY LIGHTHOUSE FESTIVALS 2020 Tour Schedule Intensity is the level of difficulty in participating in the tour (“1” being the easiest “5” being the most difficult) Fall Lighthouse Spring Lighthouse Festival Festival Friday Saturday Sunday Saturday Sunday Airplane Tours Cost Length Capacity Intensity Lunch June 12 June 13 June 14 Oct. -

How the Detective Fiction of Pd James Provokes

THEOLOGY IN SUSPENSE: HOW THE DETECTIVE FICTION OF P.D. JAMES PROVOKES THEOLOGICAL THOUGHT Jo Ann Sharkey A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of MPhil at the University of St. Andrews 2011 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/3156 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons License THE UNIVERSITY OF ST. ANDREWS ST. MARY’S COLLEGE THEOLOGY IN SUSPENSE: HOW THE DETECTIVE FICTION OF P.D. JAMES PROVOKES THEOLOGICAL THOUGHT A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF DIVINITY INSTITUTE FOR THEOLOGY, IMAGINATION, AND THE ARTS IN CANDIDANCY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY BY JO ANN SHARKEY ST. ANDREWS, SCOTLAND 15 APRIL 2010 Copyright © 2010 by Jo Ann Sharkey All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT The following dissertation argues that the detective fiction of P.D. James provokes her readers to think theologically. I present evidence from the body of James’s work, including her detective fiction that features the Detective Adam Dalgliesh, as well as her other novels, autobiography, and non-fiction work. I also present a brief history of detective fiction. This history provides the reader with a better understanding of how P.D James is influenced by the detective genre as well as how she stands apart from the genre’s traditions. This dissertation relies on an interview that I conducted with P.D. James in November, 2008. During the interview, I asked James how Christianity has influenced her detective fiction and her responses greatly contribute to this dissertation. -

Lighthouse on the Hill: the Bluefield

The Bluefield College Story Lighthouse on the Hill: Retired Senior Professor of History By: Rev. David M. Armbrister Resiliency! This is a word that aptly fits the story of Bluefield College. Financial issues have beset the school since its beginning, often giv- ing those directly associated with its operation, as well as those simply interested in its welfare, concern about its continuance as an education- al institution. If there had not been men and women of strong faith and characterized by their willingness to make great sacrifices, the college might not exist today. There would be no eighty-fifth anniversary celebration in 2007. We can be thankful for that band of men who made that trip to Bristol, Virginia in a day when travel was not easy. The enthusiasm and drive that they took with them established a model that others would follow in supporting a Baptist college and, initially, a fitting school equivalent to a high school for southwest Vir- ginia. The courage and determination that ac- companied their great belief that the school was in God’s plan continued to uplift and guide the institution through its early years. These same qualities and convictions have enabled the school to overcome its problems and emerge as one of Virginia’s leading institutions of higher learning today. The author of this work has sought to present this marvelous story in a manner that will cap- ture the unique spirit of this school and those who have been associated with it through the years. His prayer is that the story will awaken a new understanding of the service that the col- lege has rendered in its eighty-five years and provide the groundwork on which it can go for- ward in the years ahead. -

To the Lighthouse Woolf, Virginia

To the Lighthouse Woolf, Virginia Published: 1927 Categorie(s): Fiction Source: http://gutenberg.net.au 1 About Woolf: Virginia Woolf (January 25, 1882 – March 28, 1941) was an English novelist and essayist regarded as one of the foremost modernist literary figures of the twentieth century. During the interwar period, Woolf was a significant figure in London literary society and a member of the Bloomsbury Group. Her most famous works include the novels Mrs Dal- loway (1925), To the Lighthouse (1927), and Orlando (1928), and the book-length essay A Room of One's Own (1929) with its famous dictum, "a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction". Also available on Feedbooks for Woolf: • Mrs. Dalloway (1925) • A Haunted House (1921) • The Waves (1931) • Mrs Dalloway in Bond Street (1923) • Between the Acts (1941) • The New Dress (1927) • The Mark on the Wall (1917) • The Duchess and the Jeweller (1938) • The Years (1937) • An Unwritten Novel (1920) Copyright: This work is available for countries where copyright is Life+70. Note: This book is brought to you by Feedbooks http://www.feedbooks.com Strictly for personal use, do not use this file for commercial purposes. 2 Part 1 The Window 3 Chapter 1 "Yes, of course, if it's fine tomorrow," said Mrs Ramsay. "But you'll have to be up with the lark," she added. To her son these words conveyed an extraordinary joy, as if it were settled, the expedition were bound to take place, and the wonder to which he had looked forward, for years and years it seemed, was, after a night's darkness and a day's sail, within touch. -

Jack's Costume from the Episode, "There's No Place Like - 850 H

Jack's costume from "There's No Place Like Home" 200 572 Jack's costume from the episode, "There's No Place Like - 850 H... 300 Jack's suit from "There's No Place Like Home, Part 1" 200 573 Jack's suit from the episode, "There's No Place Like - 950 Home... 300 200 Jack's costume from the episode, "Eggtown" 574 - 800 Jack's costume from the episode, "Eggtown." Jack's bl... 300 200 Jack's Season Four costume 575 - 850 Jack's Season Four costume. Jack's gray pants, stripe... 300 200 Jack's Season Four doctor's costume 576 - 1,400 Jack's Season Four doctor's costume. Jack's white lab... 300 Jack's Season Four DHARMA scrubs 200 577 Jack's Season Four DHARMA scrubs. Jack's DHARMA - 1,300 scrub... 300 Kate's costume from "There's No Place Like Home" 200 578 Kate's costume from the episode, "There's No Place Like - 1,100 H... 300 Kate's costume from "There's No Place Like Home" 200 579 Kate's costume from the episode, "There's No Place Like - 900 H... 300 Kate's black dress from "There's No Place Like Home" 200 580 Kate's black dress from the episode, "There's No Place - 950 Li... 300 200 Kate's Season Four costume 581 - 950 Kate's Season Four costume. Kate's dark gray pants, d... 300 200 Kate's prison jumpsuit from the episode, "Eggtown" 582 - 900 Kate's prison jumpsuit from the episode, "Eggtown." K... 300 200 Kate's costume from the episode, "The Economist 583 - 5,000 Kate's costume from the episode, "The Economist." Kat.. -

A Corpus-Based Study of French Translations of Two Novels by Virginia Woolf

Charlotte Isabelle Aline Bosseaux Translation and Narration: A Corpus-Based Study of French Translations of two Novels by Virginia Woolf Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy from the University of London Comparative Literature University College London 2004 1 UMI Number: U602628 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U602628 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract Narratology does not usually distinguish between original and translated fiction and narratological models do not pay any attention to the translator as a discursive subject, Since the 1990’s, the visibility of translators in translated narrative texts has been increasingly discussed and researchers like Schiavi (1996) and Hermans (1996) introduced the concept of the translator’s voice, which attempts to recognise the ‘other’ voice in translation, i.e. the presence of the translator. Corpus-based studies have also focused on recurrent features of translated language (see, for example, Baker 1993, Kenny 2001; Laviosa 1997; Olohan and Baker 2000), and corpus techniques and tools are being employed to identify the translators’ ‘style’ in their translations (Baker 2000). -

Scotland, Ocean, and Archipelago in to the Lighthouse

Fairfield University DigitalCommons@Fairfield English Faculty Publications English Department 2018 Recovering Islands: Scotland, Ocean, and Archipelago in To the Lighthouse Nels C. Pearson Fairfield University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/english-facultypubs Copyright © 2018 Hofstra University The author post-print has been archived here with permission from the copyright holder. Final publisher version available here: https://read.dukeupress.edu/twentieth-century-lit/article- abstract/64/3/347/135303 Peer Reviewed Repository Citation Pearson, Nels C., "Recovering Islands: Scotland, Ocean, and Archipelago in To the Lighthouse" (2018). English Faculty Publications. 139. https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/english-facultypubs/139 Published Citation Pearson, Nels. "Recovering Islands: Scotland, Ocean, and Archipelago in To the Lighthouse." Twentieth Century Literature 64.3 (2018): 347-370. https://doi.org/10.1215/0041462X-7142083 This item has been accepted for inclusion in DigitalCommons@Fairfield by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Fairfield. It is brought to you by DigitalCommons@Fairfield with permission from the rights- holder(s) and is protected by copyright and/or related rights. You are free to use this item in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses, you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons -

The Most Beautiful Lighthouse in the World

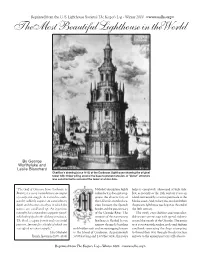

Reprinted from the U. S. Lighthouse Society's The Keeper's Log - Winter 2000 <www.uslhs.org> The Most Beautiful Lighthouse in theWorld By George Worthylake and Leslie Blanchard Chatillon's drawing (circa 1612) of the Cordouan Lighthouse showing the original tower with timber piling around the base to prevent erosion. A "donut" structure was constructed to surround the tower at a later date. “The Gulf of Gascony, from Cordouan to Michelet’s description, highly ledge is completely submerged at high tide. Biarritz, is a sea of contradictions; an enigma colored as it is, does not exag- But, as recently as the 15th century it was an of a strife and struggle. As it stretches south- gerate the chaotic fury of island connected by a narrow peninsula to the ward it suddenly acquires an extraordinary this 120-mile-stretch of sea- Medoc coast. And, in fact, was an island when depth and becomes an abyss in which the coast between the Spanish the present lighthouse was begun at the end of waters are swallowed up. An ingenious border and the great estuary the 16th century. naturalist has compared it to a gigantic funnel, of the Gironde River. The The swift, ever-shifting and unpredict- which abruptly absorbs all that pours into it. entrance of this waterway to able ocean currents rage with special violence The flood, escaping from it under an awful Bordeaux is flanked by two around the mouth of the Gironde. The entire pressure, [mounts] to a height of which our narrow channels bristling area is strewn with sunken rocks and shifting seas afford no other example.” with hidden reefs and an outcropping known sandbanks menacing the ships attempting — Jules Michelet as the Island of Cordouan. -

9 Great British Mystery Series You Won't Want to Put Down

RIOT HEADLINE COVID-19 UPDATES FROM THE BOOKISH WORLD 9 GREAT BRITISH MYSTERY SERIES YOU WON’T WANT TO PUT DOWN Emily Martin Jun 9, 2020 Looking to solve a few mysteries while you’re at home this weekend? Grab one of these great British mystery series and see how many books you can marathon read in one sitting. With page-turning mysteries like these, you won’t be able to put them down. Just be sure to have your tea, scones, and clotted cream nearby. THE ADAM DALGLIESH SERIES P.D. James’s character Adam Dalgliesh has been the protagonist of 14 mystery novels. In the first novel, Cover Her Face, Dalgliesh is a Detective Chief Inspector. In later novels, he becomes Commander in the Metropolitan Police Service at New Scotland Yard in London. In addition to these mysteries being thoughtfully plotted and compelling to read, one of the major draws to this series is of course the detective character himself. Dalgliesh is a thoughtful investigator who writes poetry in his spare time. Each mystery in this series works well as a standalone story, but it’s also fun to watch the detective’s growth throughout all 14 novels. And as an added bonus, Dalgliesh also appears as a character in P.D. James’s two novels featuring Cordelia Gray: An Unsuitable Job for a Woman and The Skull Beneath the Skin. THE LADY SHERLOCK SERIES While author Sherry Thomas is not British herself, it doesn’t get much more British than Sherlock Holmes. And in this historical mystery series, Sherry Thomas reimagines Sherlock Holmes as a female detective working under the assumed name Sherlock.