Número 23 • Octubre 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bird List Column A: 1 = 70-90% Chance Column B: 2 = 30-70% Chance Column C: 3 = 10-30% Chance

Colombia: Chocó Prospective Bird List Column A: 1 = 70-90% chance Column B: 2 = 30-70% chance Column C: 3 = 10-30% chance A B C Tawny-breasted Tinamou 2 Nothocercus julius Highland Tinamou 3 Nothocercus bonapartei Great Tinamou 2 Tinamus major Berlepsch's Tinamou 3 Crypturellus berlepschi Little Tinamou 1 Crypturellus soui Choco Tinamou 3 Crypturellus kerriae Horned Screamer 2 Anhima cornuta Black-bellied Whistling-Duck 1 Dendrocygna autumnalis Fulvous Whistling-Duck 1 Dendrocygna bicolor Comb Duck 3 Sarkidiornis melanotos Muscovy Duck 3 Cairina moschata Torrent Duck 3 Merganetta armata Blue-winged Teal 3 Spatula discors Cinnamon Teal 2 Spatula cyanoptera Masked Duck 3 Nomonyx dominicus Gray-headed Chachalaca 1 Ortalis cinereiceps Colombian Chachalaca 1 Ortalis columbiana Baudo Guan 2 Penelope ortoni Crested Guan 3 Penelope purpurascens Cauca Guan 2 Penelope perspicax Wattled Guan 2 Aburria aburri Sickle-winged Guan 1 Chamaepetes goudotii Great Curassow 3 Crax rubra Tawny-faced Quail 3 Rhynchortyx cinctus Crested Bobwhite 2 Colinus cristatus Rufous-fronted Wood-Quail 2 Odontophorus erythrops Chestnut Wood-Quail 1 Odontophorus hyperythrus Least Grebe 2 Tachybaptus dominicus Pied-billed Grebe 1 Podilymbus podiceps Magnificent Frigatebird 1 Fregata magnificens Brown Booby 2 Sula leucogaster ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WINGS ● 1643 N. Alvernon Way Ste. 109 ● Tucson ● AZ ● 85712 ● www.wingsbirds.com (866) 547 9868 Toll free US + Canada ● Tel (520) 320-9868 ● Fax (520) -

Wild Patagonia & Central Chile

WILD PATAGONIA & CENTRAL CHILE: PUMAS, PENGUINS, CONDORS & MORE! NOVEMBER 1–18, 2019 Pumas simply rock! This year we enjoyed 9 different cats! Observing the antics of lovely Amber here and her impressive family of four cubs was certainly the highlight in Torres del Paine National Park — Photo: Andrew Whittaker LEADERS: ANDREW WHITTAKER & FERNANDO DIAZ LIST COMPILED BY: ANDREW WHITTAKER VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM Sensational, phenomenal, outstanding Chile—no superlatives can ever adequately describe the amazing wildlife spectacles we enjoyed on this year’s tour to this breathtaking and friendly country! Stupendous world-class scenery abounded with a non-stop array of exciting and easy birding, fantastic endemics, and super mega Patagonian specialties. Also, as I promised from day one, everyone fell in love with Chile’s incredible array of large and colorful tapaculos; we enjoyed stellar views of all of the country’s 8 known species. Always enigmatic and confiding, the cute Chucao Tapaculo is in the Top 5 — Photo: Andrew Whittaker However, the icing on the cake of our tour was not birds but our simply amazing Puma encounters. Yet again we had another series of truly fabulous moments, even beating our previous record of 8 Pumas on the last day when I encountered a further 2 young Pumas on our way out of the park, making it an incredible 9 different Pumas! Our Puma sightings take some beating, as they have stood for the last three years at 6, 7, and 8. For sure none of us will ever forget the magical 45 minutes spent observing Amber meeting up with her four 1- year-old cubs as they joyfully greeted her return. -

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

On Birds of Santander-Bio Expeditions, Quantifying The

Facultad de Ciencias ACTA BIOLÓGICA COLOMBIANA Departamento de Biología http://www.revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/actabiol Sede Bogotá ARTÍCULO DE INVESTIGACIÓN / RESEARCH ARTICLE ZOOLOGÍA ON BIRDS OF SANTANDER-BIO EXPEDITIONS, QUANTIFYING THE COST OF COLLECTING VOUCHER SPECIMENS IN COLOMBIA Sobre las aves de las expediciones Santander-Bio, cuantificando el costo de colectar especímenes en Colombia Enrique ARBELÁEZ-CORTÉS1 *, Daniela VILLAMIZAR-ESCALANTE1 , Fernando RONDÓN-GONZÁLEZ2 1Grupo de Estudios en Biodiversidad, Escuela de Biología, Universidad Industrial de Santander, Carrera 27 Calle 9, Bucaramanga, Santander, Colombia. 2Grupo de Investigación en Microbiología y Genética, Escuela de Biología, Universidad Industrial de Santander, Carrera 27 Calle 9, Bucaramanga, Santander, Colombia. *For correspondence: [email protected] Received: 23th January 2019, Returned for revision: 26th March 2019, Accepted: 06th May 2019. Associate Editor: Diego Santiago-Alarcón. Citation/Citar este artículo como: Arbeláez-Cortés E, Villamizar-Escalante D, and Rondón-González F. On birds of Santander-Bio Expeditions, quantifying the cost of collecting voucher specimens in Colombia. Acta biol. Colomb. 2020;25(1):37-60. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/abc. v25n1.77442 ABSTRACT Several scientific reasons support continuing bird collection in Colombia, a megadiverse country with modest science financing. Despite the recognized value of biological collections for the rigorous study of biodiversity, there is scarce information on the monetary costs of specimens. We present results for three expeditions conducted in Santander (municipalities of Cimitarra, El Carmen de Chucurí, and Santa Barbara), Colombia, during 2018 to collect bird voucher specimens, quantifying the costs of obtaining such material. After a sampling effort of 1290 mist net hours and occasional collection using an airgun, we collected 300 bird voucher specimens, representing 117 species from 30 families. -

TOUR REPORT Southwestern Amazonia 2017 Final

For the first time on a Birdquest tour, the Holy Grail from the Brazilian Amazon, Rondonia Bushbird – male (Eduardo Patrial) BRAZIL’S SOUTHWESTERN AMAZONIA 7 / 11 - 24 JUNE 2017 LEADER: EDUARDO PATRIAL What an impressive and rewarding tour it was this inaugural Brazil’s Southwestern Amazonia. Sixteen days of fine Amazonian birding, exploring some of the most fascinating forests and campina habitats in three different Brazilian states: Rondonia, Amazonas and Acre. We recorded over five hundred species (536) with the exquisite taste of specialties from the Rondonia and Inambari endemism centres, respectively east bank and west bank of Rio Madeira. At least eight Birdquest lifer birds were acquired on this tour: the rare Rondonia Bushbird; Brazilian endemics White-breasted Antbird, Manicore Warbling Antbird, Aripuana Antwren and Chico’s Tyrannulet; also Buff-cheeked Tody-Flycatcher, Acre Tody-Tyrant and the amazing Rufous Twistwing. Our itinerary definitely put together one of the finest selections of Amazonian avifauna, though for a next trip there are probably few adjustments to be done. The pre-tour extension campsite brings you to very basic camping conditions, with company of some mosquitoes and relentless heat, but certainly a remarkable site for birding, the Igarapé São João really provided an amazing experience. All other sites 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Brazil’s Southwestern Amazonia 2017 www.birdquest-tours.com visited on main tour provided considerably easy and very good birding. From the rich east part of Rondonia, the fascinating savannas and endless forests around Humaitá in Amazonas, and finally the impressive bamboo forest at Rio Branco in Acre, this tour focused the endemics from both sides of the medium Rio Madeira. -

Birds of Chile a Photo Guide

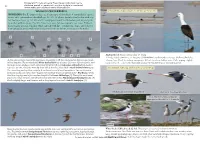

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be 88 distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical 89 means without prior written permission of the publisher. WALKING WATERBIRDS unmistakable, elegant wader; no similar species in Chile SHOREBIRDS For ID purposes there are 3 basic types of shorebirds: 6 ‘unmistakable’ species (avocet, stilt, oystercatchers, sheathbill; pp. 89–91); 13 plovers (mainly visual feeders with stop- start feeding actions; pp. 92–98); and 22 sandpipers (mainly tactile feeders, probing and pick- ing as they walk along; pp. 99–109). Most favor open habitats, typically near water. Different species readily associate together, which can help with ID—compare size, shape, and behavior of an unfamiliar species with other species you know (see below); voice can also be useful. 2 1 5 3 3 3 4 4 7 6 6 Andean Avocet Recurvirostra andina 45–48cm N Andes. Fairly common s. to Atacama (3700–4600m); rarely wanders to coast. Shallow saline lakes, At first glance, these shorebirds might seem impossible to ID, but it helps when different species as- adjacent bogs. Feeds by wading, sweeping its bill side to side in shallow water. Calls: ringing, slightly sociate together. The unmistakable White-backed Stilt left of center (1) is one reference point, and nasal wiek wiek…, and wehk. Ages/sexes similar, but female bill more strongly recurved. the large brown sandpiper with a decurved bill at far left is a Hudsonian Whimbrel (2), another reference for size. Thus, the 4 stocky, short-billed, standing shorebirds = Black-bellied Plovers (3). -

Environmental Sensitivity Index Guidelines Version 2.0

NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS ORCA 115 Environmental Sensitivity Index Guidelines Version 2.0 October 1997 Seattle, Washington noaa NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION National Ocean Service Office of Ocean Resources Conservation and Assessment National Ocean Service National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration U.S. Department of Commerce The Office of Ocean Resources Conservation and Assessment (ORCA) provides decisionmakers comprehensive, scientific information on characteristics of the oceans, coastal areas, and estuaries of the United States of America. The information ranges from strategic, national assessments of coastal and estuarine environmental quality to real-time information for navigation or hazardous materials spill response. Through its National Status and Trends (NS&T) Program, ORCA uses uniform techniques to monitor toxic chemical contamination of bottom-feeding fish, mussels and oysters, and sediments at about 300 locations throughout the United States. A related NS&T Program of directed research examines the relationships between contaminant exposure and indicators of biological responses in fish and shellfish. Through the Hazardous Materials Response and Assessment Division (HAZMAT) Scientific Support Coordination program, ORCA provides critical scientific support for planning and responding to spills of oil or hazardous materials into coastal environments. Technical guidance includes spill trajectory predictions, chemical hazard analyses, and assessments of the sensitivity of marine and estuarine environments to spills. To fulfill the responsibilities of the Secretary of Commerce as a trustee for living marine resources, HAZMAT’s Coastal Resource Coordination program provides technical support to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency during all phases of the remedial process to protect the environment and restore natural resources at hundreds of waste sites each year. -

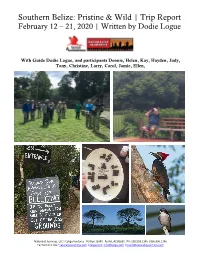

Trip Report February 12 – 21, 2020 | Written by Dodie Logue

Southern Belize: Pristine & Wild | Trip Report February 12 – 21, 2020 | Written by Dodie Logue With Guide Dodie Logue, and participants Dennis, Helen, Kay, Hayden, Judy, Tony, Christine, Larry, Carol, Jamie, Ellen, Naturalist Journeys, LLC | Caligo Ventures PO Box 16545 Portal, AZ 85632 PH: 520.558.1146 | 866.900.1146 Fax 650.471.7667 naturalistjourneys.com | caligo.com [email protected] | [email protected] Wed., Feb. 12 Early arrivals | Transfer to Crooked Tree | Pre-extension Today most of the group arrived; some had come in a day or two earlier on their own. There were airport shuttles and getting situated in the two lodges, Crooked Tree and Beck’s, which were just over a mile apart. Some of the earlier arrivals had a little time to bird the grounds of their lodge. Crooked Tree Village is a small area, NW of Belize City, about 45 minutes by car. The residents rely on tourism, as well as fishing and farming, for their livelihood. Crooked Tree Wildlife Sanctuary was established in 1984 and is run by Audubon. It encompasses around 25 square miles of government-sanctioned land, including freshwater lagoons, savannah, and broadleaf and pine woods. Some of the birds seen right on the grounds for the early arrivals were Black- cowled Oriole, Red-lored Parrot, and Lineated Woodpecker. There were two airport shuttles to pick up the various arrivals, and at 6:30 PM we all met as a group in the dining room at Beck’s for a meal of coconut curry fish, herbed chicken, and rice and beans. Hearty and delicious! Most were tired from a long travel day and, knowing about the early departure the next morning, we all went off to our lodges and were soon tucked in. -

ON 1196 NEW.Fm

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS ORNITOLOGIA NEOTROPICAL 25: 237–243, 2014 © The Neotropical Ornithological Society NON-RANDOM ORIENTATION IN WOODPECKER CAVITY ENTRANCES IN A TROPICAL RAIN FOREST Daniel Rico1 & Luis Sandoval2,3 1The University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, Nebraska. 2Department of Biological Sciences, University of Windsor, 401 Sunset Avenue, Windsor, ON, Canada, N9B3P4. 3Escuela de Biología, Universidad de Costa Rica, San Pedro, San José, Costa Rica, CP 2090. E-mail: [email protected] Orientación no al azar de las entradas de las cavidades de carpinteros en un bosque tropical. Key words: Pale-billed Woodpecker, Campephilus guatemalensis, Chestnut-colored Woodpecker, Celeus castaneus, Lineated Woodpecker, Dryocopus lineatus, Black-cheeked Woodpecker, Melanerpes pucherani, Costa Rica, Picidae. INTRODUCTION tics such as vegetation coverage of the nesting substrate, surrounding vegetation, and forest Nest site selection play’s one of the main roles age (Aitken et al. 2002, Adkins Giese & Cuth- in the breeding success of birds, because this bert 2003, Sandoval & Barrantes 2006). Nest selection influences the survival of eggs, orientation also plays an important role in the chicks, and adults by inducing variables such breeding success of woodpeckers, because the as the microclimatic conditions of the nest orientation positively influences the microcli- and probability of being detected by preda- mate conditions inside the nest cavity (Hooge tors (Viñuela & Sunyer 1992). Although et al. 1999, Wiebe 2001), by reducing the woodpecker nest site selections are well estab- exposure to direct wind currents, rainfalls, lished, the majority of this information is and/or extreme temperatures (Ardia et al. based on temperate forest species and com- 2006). Cavity entrance orientation showed munities (Newton 1998, Cornelius et al. -

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) – 2009-2012 Version Available for Download From

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) – 2009-2012 version Available for download from http://www.ramsar.org/ris/key_ris_index.htm. Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 (1990), as amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the 8th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2002) and Resolutions IX.1 Annex B, IX.6, IX.21 and IX. 22 of the 9th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2005). Notes for compilers: 1. The RIS should be completed in accordance with the attached Explanatory Notes and Guidelines for completing the Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands. Compilers are strongly advised to read this guidance before filling in the RIS. 2. Further information and guidance in support of Ramsar site designations are provided in the Strategic Framework and guidelines for the future development of the List of Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar Wise Use Handbook 14, 3rd edition). A 4th edition of the Handbook is in preparation and will be available in 2009. 3. Once completed, the RIS (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Ramsar Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the RIS and, where possible, digital copies of all maps. 1. Name and address of the compiler of this form: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. DD MM YY Beatriz de Aquino Ribeiro - Bióloga - Analista Ambiental / [email protected], (95) Designation date Site Reference Number 99136-0940. Antonio Lisboa - Geógrafo - MSc. Biogeografia - Analista Ambiental / [email protected], (95) 99137-1192. Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade - ICMBio Rua Alfredo Cruz, 283, Centro, Boa Vista -RR. CEP: 69.301-140 2. -

Colombia Trip Report Santa Marta Extension 25Th to 30Th November 2014 (6 Days)

RBT Colombia: Santa Marta Extension Trip Report - 2014 1 Colombia Trip Report Santa Marta Extension 25th to 30th November 2014 (6 days) Buffy Hummingbird by Clayton Burne Trip report compiled by tour leader: Clayton Burne RBT Colombia: Santa Marta Extension Trip Report - 2014 2 Our Santa Marta extension got off to a flying start with some unexpected birding on the first afternoon. Having arrived in Barranquilla earlier than expected, we wasted no time and headed out to the nearby Universidad del Norte – one of the best places to open our Endemics account. It took only a few minutes to find Chestnut- winged Chachalaca, and only a few more to obtain excellent views of a number of these typically localised birds. A fabulous welcome meal was then had on the 26th floor of our city skyscraper hotel! An early start the next day saw us leaving the city of Barranquilla for the nearby scrub of Caño Clarín. Our account opened quickly with a female Sapphire-throated Hummingbird followed by many Russet-throated Puffbirds. A Chestnut-winged Chachalaca by Clayton Burne White-tailed Nightjar was the surprise find of the morning. We added a number of typical species for the area including Caribbean Hornero, Scaled Dove, Green-and-rufous, Green and Ringed Kingfishers, Red-crowned, Red-rumped and Spot-breasted Woodpeckers, Stripe-backed and Bicolored Wrens, as well as Black-crested Antshrike. Having cleared up the common stuff, we headed off to Isla de Salamanca, a mangrove reserve that plays host to another very scarce endemic, the Sapphire-bellied Hummingbird. More good luck meant that the very first bird we saw after climbing out of the vehicle was the targeted bird itself. -

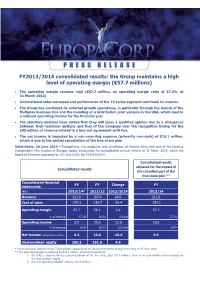

FY2013/2014 Consolidated Results: the Group Maintains a High Level of Operating Margin (€57.7 Millions)

FY2013/2014 consolidated results: the Group maintains a high level of operating margin (€57.7 millions) The operating margin remains high (€57.7 million, an operating margin ratio of 27.3% at 31 March 2014) International sales increased and performance of the TV series segment continued to improve The Group has continued its external growth operations, in particular through the launch of the Multiplex business line and the founding of a distribution joint venture in the USA, which lead to a reduced operating income for the financial year The statutory auditors have stated that they will issue a qualified opinion due to a divergence between their technical analysis and that of the Company over the recognition timing for the $45 million of revenue related to a buy-out agreement with Fox. The net income is impacted by a non-recurring expense (primarily non-cash) of €10.1 million, which is due to the partial cancellation of the free share plan Saint-Denis, 26 June 2014 – EuropaCorp, the producer and distributor of feature films and one of the leading independent film studios in Europe, today announces its consolidated annual results at 31 March 2014, which the Board of Directors approved on 25 June 2014, for FY2013/2014. Consolidated results adjusted for the impact of Consolidated results the cancelled part of the free share plan ** Consolidated financial FY FY Change FY statements (€m) 2013/14* 2012/13 2013/2014 2013/14 Revenue 211.8 185.8 26.0 211,8 Cost of sales -154.1 -129.7 -24.4 -154.1 Operating margin 57.7 56.1 1.6 57.7 % of revenue