An Ethn0archae0l06ical Study of Mabuiag Island

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mediating the Imaginary and the Space of Encounter in the Papuan Gulf Dario Di Rosa

7 Mediating the imaginary and the space of encounter in the Papuan Gulf Dario Di Rosa Writing about the 1935 Hides–O’Malley expedition in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea, the anthropologist Edward Schieffelin noted that Europeans ‘had a well-prepared category – “natives” – in which to place those people they met for the first time, a category of social subordination that served to dissipate their depth of otherness’.1 However, this category was often nuanced by Indigenous representations of neighbouring communities, producing significant effects in shaping Europeans’ understanding of their encounters. Analysing the narrative produced by Joseph Beete Jukes,2 naturalist on Francis Price Blackwood’s voyage of 1842–1846 on HMS Fly, I demonstrate the crucial role played by Torres Strait Islanders as mediators from afar of European encounters with Papuans along the coast of the Gulf of 1 Schieffelin and Crittenden 1991: 5. 2 Jukes 1847. As Beer (1996) shows, the viewing position of on-board scientists during geographical explorations was a particular one, led by their interests (see, from a different perspective, Fabian (2000) on the relevance of ‘natural history’ as episteme of accounts of explorations). This is a reminder of the high degree of social stratification within the ‘European’ micro-social community of the ship’s crew, a social hierarchy that shaped the texts available to the historians. Although he does not treat the problem of social stratification as such, see Thomas 1994 for a well-argued discussion about the different projects that guided various colonial actors. See also Dening 1992 for vivid case of power relations in the micro-social cosmos of a ship. -

Natural and Cultural Histories of the Island of Mabuyag, Torres Strait. Edited by Ian J

Memoirs of the Queensland Museum | Culture Volume 8 Part 1 Goemulgaw Lagal: Natural and Cultural Histories of the Island of Mabuyag, Torres Strait. Edited by Ian J. McNiven and Garrick Hitchcock Minister: Annastacia Palaszczuk MP, Premier and Minister for the Arts CEO: Suzanne Miller, BSc(Hons), PhD, FGS, FMinSoc, FAIMM, FGSA , FRSSA Editor in Chief: J.N.A. Hooper, PhD Editors: Ian J. McNiven PhD and Garrick Hitchcock, BA (Hons) PhD(QLD) FLS FRGS Issue Editors: Geraldine Mate, PhD PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE BOARD 2015 © Queensland Museum PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone: +61 (0) 7 3840 7555 Fax: +61 (0) 7 3846 1226 Web: qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 1440-4788 VOLUME 8 IS COMPLETE IN 2 PARTS COVER Image on book cover: People tending to a ground oven (umai) at Nayedh, Bau village, Mabuyag, 1921. Photographed by Frank Hurley (National Library of Australia: pic-vn3314129-v). NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the CEO. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed on the Queensland Museum website qm.qld.gov.au A Queensland Government Project Design and Layout: Tanya Edbrooke, Queensland Museum Printed by Watson, Ferguson & Company The geology of the Mabuyag Island Group and its part in the geological evolution of Torres Strait Friedrich VON GNIELINSKI von Gnielinski, F. -

Many Voices Queensland Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Languages Action Plan

Yetimarala Yidinji Yi rawarka lba Yima Yawa n Yir bina ach Wik-Keyangan Wik- Yiron Yam Wik Pa Me'nh W t ga pom inda rnn k Om rungu Wik Adinda Wik Elk Win ala r Wi ay Wa en Wik da ji Y har rrgam Epa Wir an at Wa angkumara Wapabura Wik i W al Ng arra W Iya ulg Y ik nam nh ar nu W a Wa haayorre Thaynakwit Wi uk ke arr thiggi T h Tjung k M ab ay luw eppa und un a h Wa g T N ji To g W ak a lan tta dornd rre ka ul Y kk ibe ta Pi orin s S n i W u a Tar Pit anh Mu Nga tra W u g W riya n Mpalitj lgu Moon dja it ik li in ka Pir ondja djan n N Cre N W al ak nd Mo Mpa un ol ga u g W ga iyan andandanji Margany M litja uk e T th th Ya u an M lgu M ayi-K nh ul ur a a ig yk ka nda ulan M N ru n th dj O ha Ma Kunjen Kutha M ul ya b i a gi it rra haypan nt Kuu ayi gu w u W y i M ba ku-T k Tha -Ku M ay l U a wa d an Ku ayo tu ul g m j a oo M angan rre na ur i O p ad y k u a-Dy K M id y i l N ita m Kuk uu a ji k la W u M a nh Kaantju K ku yi M an U yi k i M i a abi K Y -Th u g r n u in al Y abi a u a n a a a n g w gu Kal K k g n d a u in a Ku owair Jirandali aw u u ka d h N M ai a a Jar K u rt n P i W n r r ngg aw n i M i a i M ca i Ja aw gk M rr j M g h da a a u iy d ia n n Ya r yi n a a m u ga Ja K i L -Y u g a b N ra l Girramay G al a a n P N ri a u ga iaba ithab a m l j it e g Ja iri G al w i a t in M i ay Giy L a M li a r M u j G a a la a P o K d ar Go g m M h n ng e a y it d m n ka m np w a i- u t n u i u u u Y ra a r r r l Y L a o iw m I a a G a a p l u i G ull u r a d e a a tch b K d i g b M g w u b a M N n rr y B thim Ayabadhu i l il M M u i a a -

Your Labor Member in the Queensland Parliament

YOUR LABOR MEMBER IN THE QUEENSLAND PARLIAMENT Cape Vork / Douglas / Cooktown / Mareeba: Torres Strait / NPA P: 1800816264 - Fax: 07 40312437 P: 1800802391 - Fax: 07 4069 1620 PO Box 2080, Cairns 4870 PO Box 437, Thursday Island 4875 E: [email protected] E: cook.th [email protected] Submission to the Queensland Competition Authority Level 19 12 Creek Street BRISBANE QLD 4001 REVIEW OF SUN WATER PRICING STRUCTURE Submission to the Queensland Competition Authority by Jason O'Brien MP Member for Cook, on behalf of a constituent who is a Sun Water user, requesting changes to the pricing policy of Sun Water to their customers holding pension concession cards who access sun water for their domestic use only. Under the present Sun Water tariff structure they are able to negotiate how much revenue could be collected from variable and fixed charges. My submission is that Sun Water should be free to offer a Pensioner Water Subsidy Scheme for eligible pensions to reduce the impact of increased water price increases. This concession could be in the form of a rebate similar to the rate rebate scheme which applies across the state off local government rates charges. Sun Water must have the ability to provide water services to the community at a reasonable cost taking into account the most effective way to utilise the resource for the community's benefit. To this end pensions accessing Sun Water's resource purely for domestic use should be considered in a wider public interest context. Prices should be cost reflective and take into account relevant public interest matters such as pensioners accessing their resource In conclusion I submit that Sun Water should be providing a Pensioner Water Subsidy Scheme and the Queensland Competition Authority should recognise this as a public interest issue. -

LAADE W01 Sound Recordings Collected by Wolfgang Laade, 1963

Interim Finding aid LAADE_W01 Sound recordings collected by Wolfgang Laade, 1963-1965 Prepared February 2013 by MH Last updated 23 December 2016 ACCESS Availability of copies Listening copies are available. Contact the AIATSIS Audiovisual Access Unit by completing an online enquiry form or phone (02) 6261 4212 to arrange an appointment to listen to the recordings or to order copies. Restrictions on listening Some materials in this collection are restricted and may only be listened to by clients who have obtained permission from AIATSIS as well as the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community. For more details, contact Access and Client Services by sending an email to [email protected] or phone (02) 6261 4212. Restrictions on use This collection is partially restricted. It contains some materials which may only be copied by clients who have obtained permission from AIATSIS as well as the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community. For more details, contact Access and Client Services by sending an email to [email protected] or phone (02) 6261 4212. Permission must be sought from AIATSIS as well as the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community for any publication or quotation of this material. Any publication or quotation must be consistent with the Copyright Act (1968). SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE Date: 1963-1965 Extent: 82 sound tape reels (ca. 34 hrs. 30 min.) : analogue, 3 3/4 ips, 2 track, mono. ; 7 in. (not held). Production history These recordings were collected by Dr Wolfgang Laade of the Freie Universität, West Berlin, between 1963 and 1965 at various locations on Cape York Peninsula and the Torres Strait Islands, Queensland, Australia. -

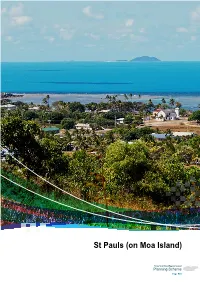

St Pauls (On Moa Island) - Local Plan Code

7.2.13 St Pauls (on Moa Island) - local plan code Part 7: Local Plans St Pauls (on Moa Island) St Pauls (on Moa Island) Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 523 Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 524 Part 7: Local Plans St Pauls (on Moa Island) Papua New Guinea Saibai Ugar Boigu Stephen Island Erub Dauan Darnley Island Masig Yorke Island Iama Mabuyag Yam Island Mer Poruma Murray Island Coconut Island Badu Kubin Moa SStt PPaulsauls Warraber Sue Island Keriri Hammond Island Mainland Australia Mainland Australia Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 525 Editor’s Note – Community Snapshot Location Topography and Environment • St Pauls is located on the eastern side of Moa • Moa Island, like other islands in the group, is Island, which is part of the Torres Strait inner and a submerged remnant of the Great Dividing near western group of islands. St Paul’s nearest Range, now separated by sea. The island neighbour is Kubin, which is located on the comprises of largely of rugged, open forest and south-western side of Moa Island. Approximately is approximately 17km in diameter at its widest 15km from the outskirts of St Pauls. point. • Native flora and fauna that have been identified Population near St Pauls include fawn leaf nosed bat, • According to the most recent census, there were grey goshawk, emerald monitor, little tern, 258 people living in St Pauls as at August 2011, red goshawk, radjah shelduck, lipidodactylus however, the population is highly transient and primilus, bare backed fruit bat, torresian tube- this may not be an accurate estimate. -

Part 16 Transport Infrastructure Plan

Figure 7.3 Option D – Rail Line from Cairns to Bamaga Torres Strait Transport Infrastructure Plan Masig (Yorke) Island Option D - Rail Line from Cairns to Bamaga Major Roads Moa Island Proposed Railway St Pauls Kubin Waiben (Thursday) Island ° 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 Kilometres Seisia Bamaga Ferry and passenger services as per current arrangements. DaymanPoint Shelburne Mapoon Wenlock Weipa Archer River Coen Yarraden Dixie Cooktown Maramie Cairns Normanton File: J:\mmpl\10303705\Engineering\Mapping\ArcGIS\Workspaces\Option D - Rail Line.mxd 29.07.05 Source of Base Map: MapData Sciences Pty Ltd Source for Base Map: MapData Sciences Pty Ltd 7.5 Option E – Option A with Additional Improvements This option retains the existing services currently operating in the Torres Strait (as per Option A), however it includes additional improvements to the connections between Horn Island and Thursday Island. Two options have been strategically considered for this connection: Torres Strait Transport Infrastructure Plan - Integrated Strategy Report J:\mmpl\10303705\Engineering\Reports\Transport Infrastructure Plan\Transport Infrastructure Plan - Rev I.doc Revision I November 2006 Page 91 • Improved ferry connections; and • Roll-on roll-of ferry. Improved ferry connections This improvement considers the combined freight and passenger services between Cairns, Bamaga and Thursday Island, with a connecting ferry service to OSTI communities. Possible improvements could include co-ordinating fares, ticketing and information services, and also improving safety, frequency and the cost of services. Roll-on roll-off ferry A roll-on roll-off operation between Thursday Island and Horn Island would provide significant benefits in moving people, cargo, and vehicles between the islands. -

Between Australia and New Guinea-Ecological and Cultural

Geographical Review of Japan Vol. 59 (Ser. B), No. 2, 69-82, 1986 Between Australia and New Guinea-Ecological and Cultural Diversity in the Torres Strait with Special Reference to the Use of Marine Resources- George OHSHIMA* The region between lowland Papua and the northern tip of the Australian continent presents a fascinating panorama of ecological, cultural and socio-economic diversity. In lowland Papua and on its associated small islands such as Saibai, Boigu and Parama, a combination of coastal forests and muddy shores dominates the scene, whereas the Torres Strait Islands of volcanic and limestone origin, together with raised coral islands and their associated reef systems present a range of island ecosystems scattered over a broad territory some 800km in extent. Coralline habitats extend south wards to the Cape York Peninsula and some parts of Arnhem Land. Coupled with those ecological diversities within a relatively small compass across the Torres Strait, the region has evoked important questions concerning the archaeological and historical dichotomy between Australian hunter-gatherers and Melanesian horticulturalists. This notion is also reflectd in terms of its complex linguistic, ethnic and political composition. In summarizing the present day cultural diversity of the region, at least three major components emerge: hunter-gatherers in the Australian Northern Territory, Australian islanders and tribal Papuans. Historically, these groups have interacted in complex ways and this has resulted in an intricate intermingling of cultures and societies. Such acculturation processes operating over thousands of years make it difficult to isolate meaning ful trends in terms of "core-periphery" components of the individual cultures. -

Abelmoschus Moschatus Subsp

Cooktown Botanic Gardens Index Plantarum 2011 Family Published Taxon Name Plate No Acanthaceae Eranthemum pulchellum Andrews 720 Acanthaceae Graptophyllum excelsum (F.Meull.) Druce 515 Acanthaceae Graptophyllum spinigerum (F.Meull.) 437 Acanthaceae Megaskepasma erythrochlamys Lindau 107 Acanthaceae Pseuderanthemum variabile (R.Br.) Radlk. 357 Adiantaceae Adiantum formosum R.Br. 761 Adiantaceae Adiantum hispidulum Sw. 762 Adiantaceae Adiantum philippense L. 765 Adiantaceae Adiantum silvaticum Tindale 763 Adiantaceae Adiantum Walsh River 764 Agavaceae Beaucarnea recurvata Lem. 399 Agavaceae Furcraea foetida (L.) Haw. 637 Agavaceae Furcraea gigantea (L.) Haw. 049 Agavaceae Yucca elephantipes Hort.ex Regel 388 Agavaceae Agave sisalana Perrine. 159 Amarylidaceae Scadoxus Raf. sp 663 Amaryllidacea, Crinum angustifolium R.Br. 536 Liliaceae Amaryllidacea, Crinum asiaticum var. procerum (Herb. et Carey) Baker 417 Liliaceae Amaryllidacea, Crinum pedunculatum R.Br. 265 Liliaceae Amaryllidacea, Crinum uniflorum F.Muell. 161 Liliaceae Amaryllidaceae Hymenocallis Salisb. americanus 046 Amaryllidaceae Hymenocallis Salisb. peruvianna 045 Amaryllidaceae Proiphys amboinensis (L.) Herb. 041 Anacardiaceae Anacardium occidentale L. 051 Anacardiaceae Buchanania arborescens (Blume) Blume. 022 Anacardiaceae Euroschinus falcatus Hook.f. var. falcatus 429 Anacardiaceae Mangifera indica L. 009 Anacardiaceae Pleiogynium timorense (DC.) Leenh. 029 Anacardiaceae Semecarpus australiensis Engl. 368 Annonaceae Annona muricata L. 054 Annonaceae Annona reticulata L. 053 Annonaceae Annona squamosa 602 Annonaceae Cananga odorata (Lam.) Hook.f.&Thomson 406 Annonaceae Melodorum leichhardtii (F.Muell.) Diels. 360 Annonaceae Rollinia deliciosa Saff. 098 Apiaceae Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. 570 Apocynaceae Adenium obesum (Forssk.) Roem. & Schult. 489 Apocynaceae Allamanda cathartica L. 047 Apocynaceae Allamanda violacea Gardn. & Field. 048 Apocynaceae Alstonia actinophylla (A.Cunn.) K.Schum. 026 Apocynaceae Alstonia scholaris (L.) R.Br. 012 Apocynaceae Alyxia ruscifolia R.Br. -

Net Primary Productivity, Global Climate Change and Biodiversity In

This file is part of the following reference: Fuentes, Mariana Menezes Prata Bezerra (2010) Vulnerability of sea turtles to climate change: a case study within the northern Great Barrier Reef green turtle population. PhD thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/11730 Vulnerability of sea turtles to climate change: A case study with the northern Great Barrier Reef green turtle population PhD thesis submitted by Mariana Menezes Prata Bezerra FUENTES (BSc Hons) February 2010 For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Earth and Environmental Sciences James Cook University Townsville, Queensland 4811 Australia “The process of learning is often more important than what is being learned” ii Statement of access I, the undersigned, author of this work, understand that James Cook University will make this thesis available for use within the University Library, via the Australian Theses Network, or by other means allow access to users in other approved libraries. I understand that as an unpublished work, a thesis has significant protection under the Copyright Act and beyond this, I do not wish to place any restriction access to this thesis. _______________________ ____________________ Signature, Mariana Fuentes Date iii Statement of sources declaration I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in any form for another degree or diploma at any university or other institution of tertiary education. Information derived from the published or unpublished work of others has been duly acknowledged in the text and a list of references is given. ________________________ _____________________ Signature, Mariana Fuentes Date iv Statement of contribution of others Research funding: . -

Publisher Version (Open Access)

EUROCENTRIC VALUES AT PLAY MODDING THE COLONIAL FROM THE INDIGENOUS PERSPECTIVE RHETT LOBAN AND THOMAS APPERLEY Indigenous people and cultures are rarely included in digital games, and if they are it is often in a rather thoughtless manner. The indigenous peoples and cultures of many parts of the world have been portrayed in digital games in several ways that show little respect or understanding of the important issues these populations face. For example, in the Australian-made Ty the Tasmanian Tiger (Electronic Arts, 2002), Australian Aboriginal people are completely absent, replaced by anthropomorphized indigenous animals some of whom wear traditional face paint, while the plot involves rescuing other animals from the “dreamtime.” So while a secularized white settler version of Aboriginal culture is a core part of the game, the people are absent. The controversial mobile game Survival Island 3: Australia Story (NIL Entertainment, 2015), was removed from the Google Play and Apple stores in January 2016, largely because of an online petition that was concerned the game encouraged violence against indigenous Australians. The game portrayed Aboriginal people as “savages” who contributed to the difficulty of surviving in the Australian outback. Other games have appropriated indigenous iconography and culture, like Mark of Kri (Sony Computer Entertainment, 2002) which used traditional Māori (the indigenous people of Aotearoa/New Zealand) facial tattoo or Tā moko on characters in the game. These examples are disappointing, and seem to represent a common 1 occurrence in commercial non-indigenous media. However, there have also recently been a number of critically acclaimed commercial gaming projects which deal with indigenous culture and issues from an indigenous perspective, for example the game Never Alone/Kisima Inŋitchuŋa (E-Line Media, 2014), made by Upper One Games in partnership with 2 Alaska’s Cook Inlet Tribal Council. -

Land & Sea Management Strategy

LAND & SEA MANAGEMENT STRATEGY for TORRES STRAIT Funded under the Natural Heritage Trust LAND & SEA MANAGEMENT STRATEGY for TORRES STRAIT Torres Strait NRM Reference Group with the assistance of Miya Isherwood, Michelle Pollock, Kate Eden and Steve Jackson November 2005 An initiative funded under the Natural Heritage Trust program of the Australian Government with support from: the Queensland Department of Natural Resources & Mines the Australian Government Department of the Environment and Heritage and the Torres Strait Regional Authority. Prepared by: Bessen Consulting Services FOREWORD The Torres Strait region is of enormous significance from a land and sea management perspective. It is a geographically and ecologically unique region, which is home to a culturally distinct society, comprised of over 20 different communities, extending from the south-western coast of Papua New Guinea (PNG) to the northern tip of Cape York Peninsula. The Torres Strait is also a very politically complex area, with an international border and a Treaty governance regime that poses unique challenges for coordinating land and sea management initiatives. Torres Strait Islander and Aboriginal people, both within and outside of the region, have strong and abiding connections with their land and sea country. While formal recognition of this relationship has been achieved through native title and other legal processes, peoples’ aspirations to sustainably manage their land and sea country have been more difficult to realise. The implementation of this Strategy, with funding from the Australian Government’s Natural Heritage Trust initiative, presents us with an opportunity to progress community-based management in our unique region, through identifying the important land and sea assets, issues, information, and potential mechanisms for supporting Torres Strait communities to sustainably manage their natural resources.