District Human Development Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hampi, Badami & Around

SCRIPT YOUR ADVENTURE in KARNATAKA WILDLIFE • WATERSPORTS • TREKS • ACTIVITIES This guide is researched and written by Supriya Sehgal 2 PLAN YOUR TRIP CONTENTS 3 Contents PLAN YOUR TRIP .................................................................. 4 Adventures in Karnataka ...........................................................6 Need to Know ........................................................................... 10 10 Top Experiences ...................................................................14 7 Days of Action .......................................................................20 BEST TRIPS ......................................................................... 22 Bengaluru, Ramanagara & Nandi Hills ...................................24 Detour: Bheemeshwari & Galibore Nature Camps ...............44 Chikkamagaluru .......................................................................46 Detour: River Tern Lodge .........................................................53 Kodagu (Coorg) .......................................................................54 Hampi, Badami & Around........................................................68 Coastal Karnataka .................................................................. 78 Detour: Agumbe .......................................................................86 Dandeli & Jog Falls ...................................................................90 Detour: Castle Rock .................................................................94 Bandipur & Nagarhole ...........................................................100 -

Disaster Management Plan – 2020-21

Chairman, District Disaster Management Authority (DDMA) Cum, Deputy Commissioner, Chikkamagaluru - 577 101 District Disaster Management Authority, Chikkamagaluru District, Karnataka Chikkamagaluru District, Karnataka 08262-230401 (O), 231499 (ADC), 231222 (Fax) [email protected], deo@[email protected], [email protected] F O R E W O R D The bounty of nature with land, water, hills and so on are the beautiful creation of God which the so-called modern human beings cannot create or replicate despite advances in science and technology. The whole responsibility lies on us to maintain God's creation in its pristine state without disturbing or intervening in the ecological balance. It is observed that the more we rise in science and technology, the less we care about protecting and maintaining our environment. Indiscriminate, improper and injudicious use of environment will result in mother nature deviating from its original path and cause hazard to human life and property in the form of disasters. Chikkamagaluru district is one of the hazard prone district in Karnataka on account of landslides, drought, floods etc. The whole of the district has faced unprecedented rains in August 2019 and 2020 which has resulted in loss of human lives and destruction of property which has taught a lesson of prudence and sustainable growth to human beings. This District Disaster Management Plan devises a strategy for reducing the hazards and dangers of all kinds of disasters and accidents. It is a dedicated effort by the DDMA, Chikkamagaluru to prepare a comprehensive District Disaster Management Plan under the leadership of the District Administration. It contains the District Profile, an assessment of vulnerability and a list of possible disasters, risk assessment, the institutional and infrastructural mechanism for facing such disasters, the preparedness of the district to overcome the disasters, an effective communication plan containing the contact numbers of Officers and the standard operating procedures for effectively dealing with the disasters which are likely to occur. -

Journal of Recent Research and Applied Studies

Original Article Mohamed et al. 2017 ISSN: 2349ISSN: 2349- 4891 – 4891 International Journal of Recent Research and Applied Studies (Multidisciplinary Open Access Refereed e-Journal) Correlations of Biomechanical Characteristics with Ball Speed in Penalty Corner Push-In Facilities and Programmes to Promote Hockey Culture in Kodagu (Coorg) District of Karnataka State Mohamed Rafuqu Pasha1 & Dr. P. Kulandivelu2 1Research Scholar, Department of Physical Education, Karpagam University, Karpagam Academy of Higher Education, Coimbatore, Tamilnadu, India. 2Associate Professor, Department of Physical Education, Karpagam University, Karpagam Academy of Higher Education, Coimbatore, Tamilnadu, India. Received 15th June 2017, Accepted 1st August 2017 Abstract Purpose of the study is to find out the facilities and programmes to promote the hockey culture in Kodagu (coorg) District of Karnataka State. For the research purpose the collected information pertaining to the study are as follows, geographical features of Kodagu (Coorg) District, Hockey game as their cultural festival, the Olympians of the Kodagu (Coorg) District, the family hockey tournament, the relationship of game with army people, various sports organizations associate the nature of the tournaments, number of schools and hockey play grounds, and facilities and programmes of the region. Keywords: Hockey, Kodagu, Coorg, Kodavas, Family, Facility, Programme. © Copy Right, IJRRAS, 2017. All Rights Reserved. Introduction Hockey Game as their Cultural Festival Karnataka is a state consisting of thirty The clan of kodavas in the Indian state administrative districts in which Kodagu (Coorg) is one of Karnataka has a long history of association with the of the smallest administrative districts in Karnataka, game of field hockey. The district of kodagu land of India Before 1956, it was an administratively separate the kodavas is considered as the cradle of Indian hockey, state called Coorg and it was merged into an enlarged they conduct hockey tournaments every year as their Mysore state. -

International Journal for Scientific Research & Development

IJSRD - International Journal for Scientific Research & Development| Vol. 3, Issue 11, 2016 | ISSN (online): 2321-0613 Landslide Susceptibility Zonation in Kallar Halla, Upper Coonoor, Lower Coonoor, Upper Katteri and Lower Katteri Watershed in Part of Nilgiris District, Tami Nadu,India using Remote Sensing and GIL Backiaraj S1 Ram MohanV2 Ramamoorthy P3 1,2,3Department of Geology 1,2University of Madras, Guindy Campus, Chennai - 600 025, Tamil Nadu, India Abstract— Landslides play an important role in the were grown and the death toll was 4 due to a 1 km long evolution of landforms and represent a serious hazard in debris slide in Selas near Ketti. Settlements where less many areas of the World. In places, fatalities and economic damaged as they were in safe zones. Since, 1978-79, the damage caused by landslides are larger than those caused by frequency of landslides has increased and the landslide other natural hazards, including earthquakes, volcanic during October, 1990, buried more than 35 families in a eruptions and floods. The Nilgiris district is located in the place called Geddai and in 1993, the landslide in southern state of Tamilnadu in India, bounded on the north Marappalam killed 12 persons, 15 were reported missing by the state of Karnataka, on the east by Coimbatore and and 21 persons were killed when two busses were washed Erode districts, on the south by Coimbatore district and on away down steep slopes (Ganapathy, Hada, 2012). In 2009, the west by the state of Kerala. Although most parts of heavy rains resulted in the death of 42 persons. -

District Disaster Management Plan (DDMP)

District Disaster Management Plan (DDMP) FOR CHIKKAMAGALURU DISTRICT 2019-20 Approved by: Chairman, District Disaster Management Authority (DDMA) Cum. Deputy Commissioner Chikkamagaluru District, Karnataka Preparerd by: District Disaster Management Authority Chikkamagaluru District, Karnataka OFFICE OF THE DEPUTY COMMISSIONER Chikkamagaluru District, Karnataka Ph: 08262-230401(O); 231499 (ADC); 231222 (Fax) e.mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] 1 P R E F A C E Chikkamagaluru district is a district with varied climatic and geographic conditions. While part of the district falls in the Malnad region, another part falls in the plain lands. Therefore the problems faced by these areas may also be different and diverse. Due to unlimited human intervention with nature and exploitation of nature, the frequency and probability of the disasters and accidents have increased drastically in the recent times. The heavy rains of August 2019 has taught the Administration to be alert and prepared for such type of disasters which are unforeseen. On the one hand heavy rains may cause floods, water logging and intense landslides, there may also be situations of drought and famine. In view of this the district has to be ready and gear itself up to meet any situation of emergency that may occur. The District Disaster Management Plan is the key for management of any emergency or disaster as the effects of unexpected disasters can be effectively addressed. This plan has been prepared based on the experiences of the past in the management of various disasters that have occurred in the district. This plan contains the blue print of the precautionary measures that need to be taken for the prevention of such disasters as well as the steps that have to be taken for ensuring that the human suffering and misery is reduced by appropriate and timely actions in rescuing the affected persons, shifting them to safer places and providing them with timely medical care and attention. -

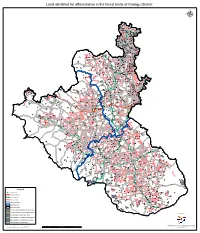

Land Identified for Afforestation in the Forest Limits of Kodagu District Μ

Land identified for afforestation in the forest limits of Kodagu District µ Hampapura Kesuru Santapura Doddakodi Malaganahalli Kasuru Mavinahalli Hosahalli Janardanahalli Nirgunda KallahalliKodlipet Mollepura Kattepura Nandipura Ramenahalli Ichalapura Ramenahalli Chikkakunda Agali Konginahalli Kattepura Mallahalli Doddakunda Basavanahalli Kudlu Besuru Nilavagilu Urugutti Lakham Kudluru Chikkabandara Bettiganahalli Korgallu Bemballur Hemmane Kiribilaha Talaguru Taluru Doddabilaha Avaredalu Lakkenahalle Siraha Hulukadu Kitturu Harohalli Toyahalli Managali Madare Bageri Dandhalli Hosahalli Bettadahalli Dundalli Mudaravalli Kujageri Kerehalli Hosapura Yedehalli Bellarhalli Kallahalli Sanivarsante Chikanahalli Huluse Gudugalale Sirangala Doddakolaturu Choudenahalli Hemmane Sidagalale Settiganahalli Doddahalli Appasethalli Gangavara Vaderapura Kyatanahalli Gopalpura Kysarahalli Bettadahalli Hittalkeri Nidta Menasa Modagadu Sigemarur Hunsekayihosahalli Mulur Ramenahalli Forest Quarters Mailatapura Mallalli Honnekopal Kurudavalli Nagur Amballi Hattihalli Badabanahalli Nandigunda Kodhalli Nagarahalli Kuti Kundahalli Heggula Bachalli Kanave Basavanahalli Harohalli Bidahalli Kumarhalli Santveri Heggademane Singanhalli Koralalhalli Basavanakoppa Hosagutti Kundahalli Inkalli Dinnehesahalli Tolur Shetthalli Hasahalli Jakhanalli Mangalur Nadenahalli Gaudahalli Malambi Sunti Ajjalli Bettadahalli Doddatolur Kugur Chikkara Santhalli Kogekodi Kantebasavanahalli Gejjihanakodu Chennapuri Alur Honnahalli Siddapura Kudigana Hirikara HitiagaddeKallahalli Sulimolate -

Kodagu District, Karnataka

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET KODAGU DISTRICT, KARNATAKA SOMVARPET KODAGU VIRAJPET SOUTH WESTERN REGION BANGALORE AUGUST 2007 FOREWORD Ground water contributes to about eighty percent of the drinking water requirements in the rural areas, fifty percent of the urban water requirements and more than fifty percent of the irrigation requirements of the nation. Central Ground Water Board has decided to bring out district level ground water information booklets highlighting the ground water scenario, its resource potential, quality aspects, recharge – discharge relationship, etc., for all the districts of the country. As part of this, Central Ground Water Board, South Western Region, Bangalore, is preparing such booklets for all the 27 districts of Karnataka state, of which six of the districts fall under farmers’ distress category. The Kodagu district Ground Water Information Booklet has been prepared based on the information available and data collected from various state and central government organisations by several hydro-scientists of Central Ground Water Board with utmost care and dedication. This booklet has been prepared by Shri M.A.Farooqi, Assistant Hydrogeologist, under the guidance of Dr. K.Md. Najeeb, Superintending Hydrogeologist, Central Ground Water Board, South Western Region, Bangalore. I take this opportunity to congratulate them for the diligent and careful compilation and observation in the form of this booklet, which will certainly serve as a guiding document for further work and help the planners, administrators, hydrogeologists and engineers to plan the water resources management in a better way in the district. Sd/- (T.M.HUNSE) Regional Director KODAGU DISTRICT AT A GLANCE Sl.No. -

Status of Stree Shakti Groups in Karnataka

www.ijird.com April, 2016 Vol 5 Issue 5 ISSN 2278 – 0211 (Online) Status of Stree Shakti Groups in Karnataka Geeta Koogi Research Scholar, Department of Studies in Economics, Karnataka University, Dharwad, India Dr. S. T. Bagalkoti Professor, Department of Studies in Economics, Karnataka University, Dharwad, India Abstract: The present study deals with the streeshakti groups in Karnataka, StreeShakthi Groups (SSGs) are formed at the village level to inculcate the savings habit in the members empowering the women economically. About 15 to 20 women members who are from below poverty line families, landless agricultural labourers. The aim of the present paper is reviewing the growth and commenting on the present status of the government sponsored SHGs in Karnataka. The data is compiled from the Statistical Abstracts of Karnataka and Karnataka at a Glance for various years. The data is analyzed using simple statistical tools like growth rates, percentage shares, and ratios. Principal component analysis is employed to construct composite indices of SHG development. The state had formed 1.40 lakh SSGs with a membership of more than 20 lakh women members, the coverage of members was hardly 14% of the eligible population in the state. Keywords: Stree Shakti groups, women empowerment, micro credit, rural employment, rural women 1. Introduction Many types of development interventions are implemented through different institutions and agencies. Poverty is still a very huge social malady and in most countries poverty has a significant gender dimension as the work of women is often not accounted for and hence not paid. Therefore, poverty alleviation, through schemes for women empowerment, is expected to strengthen women economically and make their contribution to household income count in the real sense. -

Expectant Urbanism Time, Space and Rhythm in A

EXPECTANT URBANISM TIME, SPACE AND RHYTHM IN A SMALLER SOUTH INDIAN CITY by Ian M. Cook Submitted to Central European University Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisors: Professor Daniel Monterescu CEU eTD Collection Professor Vlad Naumescu Budapest, Hungary 2015 Statement I hereby state that the thesis contains no material accepted for any other degrees in any other institutions. The thesis contains no materials previously written and/or published by another person, except where appropriate acknowledgment is made in the form of bibliographical reference. Budapest, November, 2015 CEU eTD Collection Abstract Even more intense than India's ongoing urbanisation is the expectancy surrounding it. Freed from exploitative colonial rule and failed 'socialist' development, it is loudly proclaimed that India is having an 'urban awakening' that coincides with its 'unbound' and 'shining' 'arrival to the global stage'. This expectancy is keenly felt in Mangaluru (formerly Mangalore) – a city of around half a million people in coastal south Karnataka – a city framed as small, but with metropolitan ambitions. This dissertation analyses how Mangaluru's culture of expectancy structures and destructures everyday urban life. Starting from a movement and experience based understanding of the urban, and drawing on 18 months ethnographic research amongst housing brokers, moving street vendors and auto rickshaw drivers, the dissertation interrogates the interplay between the city's regularities and irregularities through the analytical lens of rhythm. Expectancy not only engenders violent land grabs, slum clearances and the creation of exclusive residential enclaves, but also myriad individual and collective aspirations in, with, and through the city – future wants for which people engage in often hard routinised labour in the present. -

BEDS DETAILS in GOVERNMENT HOSPITALS AS on 05/07/2021 Total Beds Alloted for Covid-19 Occupied Unoccupied S

Government of Karnataka COVID-19 War Room, Mysuru Daily Report COVID-19 Positive Cases Analysis of Mysuru District as on 05/0 7/2021 (as on 07:30 PM) Mysuru District COVID -19 War Room, DC Office, Mysuru Page 1 of 27 Prepared By – District Covid-19 War Room MYSURU DISTRICT COVID WAR ROOM MEDIA BULLETIN DATED : 05-07-2021 Situation till: 6:00 PM Screening of all COVID -19 suspects continues Summary as below: Total number of persons observed to date 815691 Total number of persons who have completed 7 days of isolation 637323 Total number of persons isolated in the home for 7 days 10211 Total 3678 Isolated in Dedicated COVID Government 281 hospital's Private 968 Isolated in Dedicated COVID Government 88 Total active cases Health Care Private 221 Government 462 Isolated in COVID Care Centers Private 0 Isolated in Home 1658 Today's Samples Tested 10903 Total samples Tested Total 1591351 Today's Positive Cases 371 Cumulative Positive's 168157 Today's Discharge 490 Cumulative Discharged 162270 Today's Death 6 Cumulative Death’s 2209 Page 2 of 27 Prepared By – District Covid-19 War Room ANALYSIS AND ANALYTICS OF CORONA POSITIVE PATIENTS IN MYSURU DISTRICT (as on 05.07.2021 at 07:30 PM) Total Cases 168157 Total Recovered 162270 Total Death 2209 New Cases in last 24 371 Hrs Positive Death Sl Positive Active Death cases in TALUK Discharges cases No Cases Cases cases last 24 reported hours 1 H.D.KOTE 5158 4966 131 61 16 0 2 HUNSUR 9393 8985 324 84 50 2 3 K.R.NAGAR 9998 9540 377 81 47 0 4 NANJANGUDU 10630 10238 269 123 12 0 5 PERIYAPATNA 6633 6150 -

Thinking the Future: Coffee, Forests and People

Thinking the Future: Coffee, Forests and People Conservation and development in Kodagu Advanced Master « Forêt Nature Société » - 2011 Maya Leroy, Claude Garcia, Pierre-Marie Aubert, Vendé Jérémy Claire Bernard, Joëlle Brams, Charlène Caron, Claire Junker, Guillaume Payet, Clément Rigal, Samuel Thevenet AgroParisTech -ENGREF Environmental evaluation training course TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ....................................................................................................3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................5 I. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 15 II. METHODS ................................................................................................................ 19 II.1. TERRITORIAL PROSPECTIVE: GOALS AND OBJECTIVES .......................................................19 II.2. UNDERSTANDING THE TERRITORY: A STRATEGIC DIAGNOSIS ............................................21 II.3. INTERVIEWING TO UNDERSTAND PRESENT STRATEGIES AND IMAGINE FUTURE CHANGES 21 II.4. IMPLEMENTING OUR METHODOLOGY: A FOUR STEP APPROACH.........................................24 III. LANDSCAPE MODEL ......................................................................................... 27 III.1. HEURISTIC MODEL: REPRESENTING THE LANDSCAPE ...................................................28 III.2. COUNTERBALANCING EVOLUTION FACTORS: CONFLICTS AND LAND TENURE SYSTEM -

Contextualizing the Contemporary Caste Count

THE POLITICS OF THE COUNT: Caste in Contemporary India By Trina Vithayathil B.A., Carleton College, 1998 M.P.P., Harvard University, 2002 M.A., Brown University, 2010 Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Sociology at Brown University PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND MAY 2014 @ COPYRIGHT Trina Vithayathil 2014 ii This dissertation by Trina Vithayathil is accepted in its present form by the Department of Sociology as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date__________________ __________________________________ Leah K. VanWey, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date__________________ __________________________________ Patrick Heller, Committee Member Date__________________ __________________________________ José Itzigsohn, Committee Member Date__________________ __________________________________ Paget Henry, Reader Date__________________ __________________________________ Gregory Elliott, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date__________________ __________________________________ Peter M. Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii VITAE Trina Vithayathil, born in St. Louis, MO, attended parochial and public schools before completing her B.A. in Geology at Carleton College in 1998. After working for two years at the U.S. Geological Survey‘s National Earthquake Information Center in Golden, CO she completed an M.P.P. in political and economic development at Harvard University‘s Kennedy School of Government in 2002, where she was a Public Service Fellow. She then spent several years working in Bangalore, India at the Public Affairs Centre and in New York City, NY at the Program on Forced Migration and Health at Columbia University, among other places, during which time she taught as an adjunct lecturer in the Political Science Department at Hunter College.