Contextualizing the Contemporary Caste Count

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hampi, Badami & Around

SCRIPT YOUR ADVENTURE in KARNATAKA WILDLIFE • WATERSPORTS • TREKS • ACTIVITIES This guide is researched and written by Supriya Sehgal 2 PLAN YOUR TRIP CONTENTS 3 Contents PLAN YOUR TRIP .................................................................. 4 Adventures in Karnataka ...........................................................6 Need to Know ........................................................................... 10 10 Top Experiences ...................................................................14 7 Days of Action .......................................................................20 BEST TRIPS ......................................................................... 22 Bengaluru, Ramanagara & Nandi Hills ...................................24 Detour: Bheemeshwari & Galibore Nature Camps ...............44 Chikkamagaluru .......................................................................46 Detour: River Tern Lodge .........................................................53 Kodagu (Coorg) .......................................................................54 Hampi, Badami & Around........................................................68 Coastal Karnataka .................................................................. 78 Detour: Agumbe .......................................................................86 Dandeli & Jog Falls ...................................................................90 Detour: Castle Rock .................................................................94 Bandipur & Nagarhole ...........................................................100 -

Journal of Recent Research and Applied Studies

Original Article Mohamed et al. 2017 ISSN: 2349ISSN: 2349- 4891 – 4891 International Journal of Recent Research and Applied Studies (Multidisciplinary Open Access Refereed e-Journal) Correlations of Biomechanical Characteristics with Ball Speed in Penalty Corner Push-In Facilities and Programmes to Promote Hockey Culture in Kodagu (Coorg) District of Karnataka State Mohamed Rafuqu Pasha1 & Dr. P. Kulandivelu2 1Research Scholar, Department of Physical Education, Karpagam University, Karpagam Academy of Higher Education, Coimbatore, Tamilnadu, India. 2Associate Professor, Department of Physical Education, Karpagam University, Karpagam Academy of Higher Education, Coimbatore, Tamilnadu, India. Received 15th June 2017, Accepted 1st August 2017 Abstract Purpose of the study is to find out the facilities and programmes to promote the hockey culture in Kodagu (coorg) District of Karnataka State. For the research purpose the collected information pertaining to the study are as follows, geographical features of Kodagu (Coorg) District, Hockey game as their cultural festival, the Olympians of the Kodagu (Coorg) District, the family hockey tournament, the relationship of game with army people, various sports organizations associate the nature of the tournaments, number of schools and hockey play grounds, and facilities and programmes of the region. Keywords: Hockey, Kodagu, Coorg, Kodavas, Family, Facility, Programme. © Copy Right, IJRRAS, 2017. All Rights Reserved. Introduction Hockey Game as their Cultural Festival Karnataka is a state consisting of thirty The clan of kodavas in the Indian state administrative districts in which Kodagu (Coorg) is one of Karnataka has a long history of association with the of the smallest administrative districts in Karnataka, game of field hockey. The district of kodagu land of India Before 1956, it was an administratively separate the kodavas is considered as the cradle of Indian hockey, state called Coorg and it was merged into an enlarged they conduct hockey tournaments every year as their Mysore state. -

List of Successful Candidates

11 - LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES CONSTITUENCY WINNER PARTY Andhra Pradesh 1 Nagarkurnool Dr. Manda Jagannath INC 2 Nalgonda Gutha Sukender Reddy INC 3 Bhongir Komatireddy Raj Gopal Reddy INC 4 Warangal Rajaiah Siricilla INC 5 Mahabubabad P. Balram INC 6 Khammam Nama Nageswara Rao TDP 7 Aruku Kishore Chandra Suryanarayana INC Deo Vyricherla 8 Srikakulam Killi Krupa Rani INC 9 Vizianagaram Jhansi Lakshmi Botcha INC 10 Visakhapatnam Daggubati Purandeswari INC 11 Anakapalli Sabbam Hari INC 12 Kakinada M.M.Pallamraju INC 13 Amalapuram G.V.Harsha Kumar INC 14 Rajahmundry Aruna Kumar Vundavalli INC 15 Narsapuram Bapiraju Kanumuru INC 16 Eluru Kavuri Sambasiva Rao INC 17 Machilipatnam Konakalla Narayana Rao TDP 18 Vijayawada Lagadapati Raja Gopal INC 19 Guntur Rayapati Sambasiva Rao INC 20 Narasaraopet Modugula Venugopala Reddy TDP 21 Bapatla Panabaka Lakshmi INC 22 Ongole Magunta Srinivasulu Reddy INC 23 Nandyal S.P.Y.Reddy INC 24 Kurnool Kotla Jaya Surya Prakash Reddy INC 25 Anantapur Anantha Venkata Rami Reddy INC 26 Hindupur Kristappa Nimmala TDP 27 Kadapa Y.S. Jagan Mohan Reddy INC 28 Nellore Mekapati Rajamohan Reddy INC 29 Tirupati Chinta Mohan INC 30 Rajampet Annayyagari Sai Prathap INC 31 Chittoor Naramalli Sivaprasad TDP 32 Adilabad Rathod Ramesh TDP 33 Peddapalle Dr.G.Vivekanand INC 34 Karimnagar Ponnam Prabhakar INC 35 Nizamabad Madhu Yaskhi Goud INC 36 Zahirabad Suresh Kumar Shetkar INC 37 Medak Vijaya Shanthi .M TRS 38 Malkajgiri Sarvey Sathyanarayana INC 39 Secundrabad Anjan Kumar Yadav M INC 40 Hyderabad Asaduddin Owaisi AIMIM 41 Chelvella Jaipal Reddy Sudini INC 1 GENERAL ELECTIONS,INDIA 2009 LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATE CONSTITUENCY WINNER PARTY Andhra Pradesh 42 Mahbubnagar K. -

Nuclear Issues

YEAR 2013 Select Questions and Answers from the Indian Parliament on Nuclear Issues Compiled by Centre for Nuclear & Arms Control 1, Development Enclave, Rao Tula Ram Marg, New Delhi-110010 Visit us: www.idsa.in Nuclear and Arms Control Centre GOVERNMENT OF INDIA DEPARTMENT OF ATOMIC ENERGY LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO.475 TO BE ANSWERED ON 27.02.2013 PROTEST AGAINST NUCLEAR POWER PLANTS 475. SHRI SYED SHAHNAWAZ HUSSAIN: Will the PRIME MINISTER be pleased to state: (a) whether in view of the violent protests against the proposed Kudankulam and Jaitapur Nuclear Power Plants, the Nuclear Power Corporation of India Ltd. has launched a nation wide organised campaign to allay the public apprehensions regarding radioactive radiations from these plants; (b) if so, the details thereof; and (c) if not, the reasons therefor? ANSWER THE MINISTER OF STATE FOR PERSONNEL, PUBLIC GRIEVAN CES & PENSIONS AND PRIME MINISTER’S OFFICE (SHRI V. NARAYANNASAMY): (a) to (c) The ongoing public outreach programmes were intensified following the Fukushima incident to allay the people’s apprehensions about safety of nuclear power, radiation and other related aspects in a credible and structured manner. Nuclear Power Corporation of India Limited (NPCIL) has scaled up these programmes adopting a multi-pronged approach. The focus of the outreach have been the local community, decision makemakers & people’s representatives, press and media, students & teachers, opinion makers, and the public at large. The efforts included creation of appropriate public awareness materials and their dissemination to all target groups. **** (http://dae.nic.in/writereaddata/parl/bud2013/lsus475.pdf) Visit us: www.idsa.in 1 Nuclear and Arms Control Centre GOVERNMENT OF INDIA DEPARTMENT OF ATOMIC ENERGY LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO.526 TO BE ANSWERED ON 27.02.2013 SETTING UP OF HEAVY WATER UNIT 526. -

Karnataka, India

Natural Perception by Kodagu communities Georgina Zamora - Karnataka, India- UNIVERSITAT AUTÒNOMA DE BARCELONA Tutor Victoria Reyes-García, ICREA Ethnoecology Laboratory Georgina Zamora Quílez Degree on Environmental Sciences 1 Natural Perception by Kodagu communities Georgina Zamora Detailed Index Advertisement ............................................................................................................. 5 Acknowledgments ....................................................................................................... 6 I. INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................ 7 II. LITERATURE REVISION .......................................................................................... 8 1. Natural Capital Origins ............................................................................................. 8 2. Natural Goods and services....................................................................................... 9 2.1 Natural resources............................................................................................... 9 2.2 Ecosystem services ............................................................................................ 9 2.3 NNRR/Ecosystem services and sustainable development ..................................... 10 3 Natural Capital........................................................................................................ 11 3.1 Concept.......................................................................................................... -

Myths and Beliefs on Sacred Groves Among Kembatti Communities: a Case Study from Kodagu District, South-India

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH CULTURE SOCIETY ISSN: 2456-6683 Volume - 1, Issue - 10, Dec – 2017 UGC Approved Monthly, Peer-Reviewed, Refereed, Indexed Journal Impact Factor: 3.449 Publication Date: 31/12/2017 Myths and beliefs on sacred groves among Kembatti communities: A case study from Kodagu District, South-India Goutham A M.1, Annapurna M 2 1Research Scholar, Department of Studies in Anthropology, University of Mysore, Manasagangothri, Mysore, India 2Professor, Department of Studies in Anthropology(Rtd), University of Mysore, Manasagangothri, Mysore, India Email – [email protected] Abstract: Sacred groves are forest patches of pristine vegetation left untouched by the local inhabitants for centuries in the name of deities, related socio-cultural beliefs and taboos. Though the different scientists defined it from various points of view, the central idea or the theme of sacred grove remains the same. Conservation of natural resources through cultural and religious beliefs has been the practice of diverse communities in India, resulting in the occurrence of sacred groves all over the country. Though they are found in all bio-geographical realms of the country, maximum number of sacred groves is reported from Western Ghats, North East India and Central India. In Karnataka, sacred groves are known by many local names such as: Devarakadu, Kaan forest, Siddaravana, Nagabana, Bana etc. This paper gives detailed insight on sacred groves of kodagu District of Karnataka. Indigenous communities like Kembatti Holeyas and Kudiyas defined them as ‘tracts of virgin forest that were left untouched, harbour rich biodiversity, and are protected by the local people due to their cultural and religious beliefs and taboos that the deities reside in them and protect the villagers from different calamities’. -

List of Winning Candidated Final for 16Th

Leading/Winning State PC No PC Name Candidate Leading/Winning Party Andhra Pradesh 1 Adilabad Rathod Ramesh Telugu Desam Andhra Pradesh 2 Peddapalle Dr.G.Vivekanand Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 3 Karimnagar Ponnam Prabhakar Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 4 Nizamabad Madhu Yaskhi Goud Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 5 Zahirabad Suresh Kumar Shetkar Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 6 Medak Vijaya Shanthi .M Telangana Rashtra Samithi Andhra Pradesh 7 Malkajgiri Sarvey Sathyanarayana Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 8 Secundrabad Anjan Kumar Yadav M Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 9 Hyderabad Asaduddin Owaisi All India Majlis-E-Ittehadul Muslimeen Andhra Pradesh 10 Chelvella Jaipal Reddy Sudini Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 11 Mahbubnagar K. Chandrasekhar Rao Telangana Rashtra Samithi Andhra Pradesh 12 Nagarkurnool Dr. Manda Jagannath Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 13 Nalgonda Gutha Sukender Reddy Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 14 Bhongir Komatireddy Raj Gopal Reddy Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 15 Warangal Rajaiah Siricilla Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 16 Mahabubabad P. Balram Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 17 Khammam Nama Nageswara Rao Telugu Desam Kishore Chandra Suryanarayana Andhra Pradesh 18 Aruku Deo Vyricherla Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 19 Srikakulam Killi Krupa Rani Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 20 Vizianagaram Jhansi Lakshmi Botcha Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 21 Visakhapatnam Daggubati Purandeswari -

Review of Research Issn: 2249-894X Impact Factor : 5.7631(Uif) Ugc Approved Journal No

Review of ReseaRch issN: 2249-894X impact factoR : 5.7631(Uif) UGc appRoved JoURNal No. 48514 volUme - 8 | issUe - 9 | JUNe - 2019 A SOCIAL AND CULTURAL STUDY OF WOMEN IN KARNATAKA (1900-2020) Khajappa Itaga1 and Dr. Sarvodaya S. S.2 1Research Student 2M.A., M.Phil., Ph.D , Reserch Guide, Associate Professor, Post Graduate Department of Studies in History Government College, Kalaburagi. ABSTRACT: Culture assumes a significant job in the advancement of any country. It speaks to a lot of shared frames of mind, qualities, objectives and practices. Culture and inventiveness show themselves in practically all financial, social and different exercises. A nation as differing as India is symbolized by the majority of its way of life. India has one of the world's biggest assortments of melodies, music, move, theater, society customs, performing expressions, rituals and ceremonies, works of art and compositions that are known, as the 'Immaterial Cultural Heritage' (ICH) of mankind. So as to save these components, the Ministry of Culture actualizes various plans and projects planned for giving money related help to people, gatherings and social associations occupied with performing, visual and artistic expressions and so on. KEYWORDS: Culture assumes , qualities, objectives and practices. INTRODUCTION : surprisingly. Karnataka has hurled Mansur, T. Chaudiah, K.K.Hebbar, Karnataka's social legacy is remarkable characters of Panith Bheemasen Joshi, Gangubai rich and variegated. Kannada authentic criticalness. In the Hangal, B.V. Karanth U.R. Anantha writing saw its first work melodic guide of India, the State Murthy, Girish Karnad, during ninth Century and in has brilliant spots, regardless of Chandrashekar Kambar are a quite a while it has made whether it is Hindustani or couple of brilliant appearances seven champs of Jnanapeetha Karnatak, the last having started that sparkle forward. -

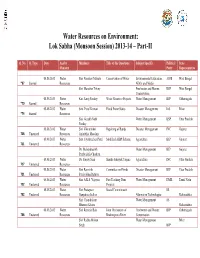

Water Resources on Environment: Lok Sabha (Monsoon Session) 2013-14 – Part-II

Water Resources on Environment: Lok Sabha (Monsoon Session) 2013-14 – Part-II Q. No. Q. Type Date Ans by Members Title of the Questions Subject Specific Political State Ministry Party Representative 08.08.2013 Water Shri Narahari Mahato Conservation of Water Environmental Education, AIFB West Bengal *67 Starred Resources NGOs and Media Shri Manohar Tirkey Freshwater and Marine RSP West Bengal Conservation 08.08.2013 Water Km. Saroj Pandey Water Resource Projects Water Management BJP Chhattisgarh *70 Starred Resources 08.08.2013 Water Smt. Putul Kumari Flood Prone States Disaster Management Ind. Bihar *74 Starred Resources Shri Gorakh Nath Water Management BSP Uttar Pradesh Pandey 08.08.2013 Water Shri Vikrambhai Repairing of Bunds Disaster Management INC Gujarat 708 Unstarred Resources Arjanbhai Maadam 08.08.2013 Water Smt. Jayshreeben Patel Modified AIBP Scheme Agriculture BJP Gujarat 711 Unstarred Resources Dr. Mahendrasinh Water Management BJP Gujarat Pruthvisinh Chauhan 08.08.2013 Water Dr. Sanjay Sinh Sharda Sahayak Yojana Agriculture INC Uttar Pradesh 717 Unstarred Resources 08.08.2013 Water Shri Ramsinh Committee on Floods Disaster Management BJP Uttar Pradesh 721 Unstarred Resources Patalyabhai Rathwa 08.08.2013 Water Shri A.K.S. Vijayan Fast Tracking Dam Water Management DMK Tamil Nadu 722 Unstarred Resources Projects 08.08.2013 Water Shri Prataprao Social Commitment SS 752 Unstarred Resources Ganpatrao Jadhav Alternative Technologies Maharashtra Shri Chandrakant Water Management SS Bhaurao Khaire Maharashtra 08.08.2013 Water -

Parliamentary Bulletin

RAJYA SABHA Parliamentary Bulletin PART-II Nos.: 51236-51237] WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 4, 2013 No. 51236 Committee Co-ordination Section Meeting of the Parliamentary Forum on Youth As intimated by the Lok Sabha Secretariat, a meeting of the Parliamentary Forum on Youth on the subject ‘Youth and Social Media: Challenges and Opportunities’ will be held on Thursday, 05 September, 2013 at 1530 hrs. in Committee Room No.074, Ground Floor, Parliament Library Building, New Delhi. Shri Naman Pugalia, Public Affairs Analyst, Google India will make a presentation. 2. Members are requested to kindly make it convenient to attend the meeting. ——— No. 51237 Committee Co-ordination Section Re-constitution of the Department-related Parliamentary Standing Committees (2013-2014) The Department–related Parliamentary Standing Committees have been reconstituted w.e.f. 31st August, 2013 as follows: - Committee on Commerce RAJYA SABHA 1. Shri Birendra Prasad Baishya 2. Shri K.N. Balagopal 3. Shri P. Bhattacharya 4. Shri Shadi Lal Batra 2 5. Shri Vijay Jawaharlal Darda 6. Shri Prem Chand Gupta 7. Shri Ishwarlal Shankarlal Jain 8. Shri Shanta Kumar 9. Dr. Vijay Mallya 10. Shri Rangasayee Ramakrishna LOK SABHA 11. Shri J.P. Agarwal 12. Shri G.S. Basavaraj 13. Shri Kuldeep Bishnoi 14. Shri C.M. Chang 15. Shri Jayant Chaudhary 16. Shri K.P. Dhanapalan 17. Shri Shivaram Gouda 18. Shri Sk. Saidul Haque 19. Shri S. R. Jeyadurai 20. Shri Nalin Kumar Kateel 21. Shrimati Putul Kumari 22. Shri P. Lingam 23. Shri Baijayant ‘Jay’ Panda 24. Shri Kadir Rana 25. Shri Nama Nageswara Rao 26. Shri Vishnu Dev Sai 27. -

Shri Kamal Nath

LOK SABHA ___ SYNOPSIS OF DEBATES (Proceedings other than Questions & Answers) ______ Monday, June 1, 2009 / Jyaistha 11, 1931 (Saka) ______ NATIONAL ANTHEM The National Anthem was played OBSERVANCE OF SILENCE MR. SPEAKER PRO TEM (SHRI MANIKRAO HODLYA GAVIT): We are meeting today on a solemn occasion. A new Lok Sabha has been elected under the Constitution charged with great and heavy responsibilities for the welfare of the country and our people. It is fit and proper, as is customary on such an occasion, that we all stand in silence for a short while before we begin our proceedings. The Members then stood in silence for a short while ANNOUNCEMENT BY SPEAKER PRO TEM Welcome to the Members of New Lok Sabha MR. SPEAKER PRO TEM: It gives me great pleasure to welcome all the Members who have been elected to the Fifteenth Lok Sabha. I am sure you will all help the Chair in Maintaining the high traditions of this House and thereby strengthening the roots of parliamentary democracy in our country. I wish you all success in your endeavours. RESIGNATION BY MEMBER MR. SPEAKER PRO TEM: I have to inform the house that the Speaker had received a letter dated the 21 May, 2009 from Shri Akhilesh Yadav, an elected Member from Firozabad and Kannauj constituencies of Uttar Pradesh resigning from the membership of Lok Sabha from the Firozabad constituency of Uttar Pradesh. The Speaker has accepted his resignation with effect from 26th May, 2009. OATH OR AFFIRMATION The following 335 members took the oath or made the affirmation as follows, signed the Roll of members and took their seats in the House. -

Being Brahmin, Being Modern

Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:12 24 May 2016 Being Brahmin, Being Modern Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:12 24 May 2016 ii (Blank) Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:12 24 May 2016 Being Brahmin, Being Modern Exploring the Lives of Caste Today Ramesh Bairy T. S. Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:12 24 May 2016 First published 2010 by Routledge 912–915 Tolstoy House, 15–17 Tolstoy Marg, New Delhi 110 001 Simultaneously published in UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Transferred to Digital Printing 2010 © 2010 Ramesh Bairy T. S. Typeset by Bukprint India B-180A, Guru Nanak Pura, Laxmi Nagar Delhi 110 092 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 978-0-415-58576-7 Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:12 24 May 2016 For my parents, Smt. Lakshmi S. Bairi and Sri. T. Subbaraya Bairi. And, University of Hyderabad. Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:12 24 May 2016 vi (Blank) Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:12 24 May 2016 Contents Acknowledgements ix Chapter 1 Introduction: Seeking a Foothold