The Role of Reasoning and Persuasion in Legal Argumentation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Pragmatic Study of Fallacy in George W. Bush's Political Speeches Pjaee, 17(12) (2020)

A PRAGMATIC STUDY OF FALLACY IN GEORGE W. BUSH'S POLITICAL SPEECHES PJAEE, 17(12) (2020) A PRAGMATIC STUDY OF FALLACY IN GEORGE W. BUSH'S POLITICAL SPEECHES Dr. Ghanim Jwaid Al-Sieedy1, Haider Rajih Wadaah Al-Jilihawi2 1,2University of Karbala - College of Education. Dr. Ghanim Jwaid Al-Sieedy , Haider Rajih Wadaah Al-Jilihawi , A Pragmatic Study Of Fallacy In George W. Bush's Political Speeches , Palarch’s Journal Of Archaeology Of Egypt/Egyptology 18(4). ISSN 1567-214x. Keywords: Political speeches, Pragmatics, Fallacy, Argument. Abstract: A fallacy can be described as the act of issuing a faulty argument to support and reinforce a previously published argument for purposes of persuasion. However, a fallacy is a broad subject that has been addressed from several viewpoints. A few experiments have tried to counter the fallacy pragmatically. However, the attempts above have suffered from shortcomings, which made them incomplete accounts in this regard. Hence, this study has set itself to provide pragmatic models for the analysis of fallacy as far as its pragmatic structure, forms, methods, and applications are concerned. These models use many models produced by several academics and the researchers themselves' observations. The validity of the established models was tested by reviewing seven speeches by George W. Bush taken before and after the war in Iraq (2002-2008). The analyses demonstrated the efficacy of the models created. Mostly because they have yielded varied results, it is clear that fallacy is a process of stages, with each round distinct for its pragmatic components and strategies. 1. Introduction: The fallacy has been regarded as a critical issue by numerous studies investigating the definition from different lenses. -

From Logic to Rhetoric: a Contextualized Pedagogy for Fallacies

Current Issue From the Editors Weblog Editorial Board Editorial Policy Submissions Archives Accessibility Search Composition Forum 32, Fall 2015 From Logic to Rhetoric: A Contextualized Pedagogy for Fallacies Anne-Marie Womack Abstract: This article reenvisions fallacies for composition classrooms by situating them within rhetorical practices. Fallacies are not formal errors in logic but rather persuasive failures in rhetoric. I argue fallacies are directly linked to successful rhetorical strategies and pose the visual organizer of the Venn diagram to demonstrate that claims can achieve both success and failure based on audience and context. For example, strong analogy overlaps false analogy and useful appeal to pathos overlaps manipulative emotional appeal. To advance this argument, I examine recent changes in fallacies theory, critique a-rhetorical textbook approaches, contextualize fallacies within the history and theory of rhetoric, and describe a methodology for rhetorically reclaiming these terms. Today, fallacy instruction in the teaching of written argument largely follows two paths: teachers elevate fallacies as almost mathematical formulas for errors or exclude them because they don’t fit into rhetorical curriculum. Both responses place fallacies outside the realm of rhetorical inquiry. Fallacies, though, are not as clear-cut as the current practice of spotting them might suggest. Instead, they rely on the rhetorical situation. Just as it is an argument to create a fallacy, it is an argument to name a fallacy. This article describes an approach in which students must justify naming claims as successful strategies and/or fallacies, a process that demands writing about contexts and audiences rather than simply linking terms to obviously weak statements. -

Circular Reasoning

Cognitive Science 26 (2002) 767–795 Circular reasoning Lance J. Rips∗ Department of Psychology, Northwestern University, 2029 Sheridan Road, Evanston, IL 60208, USA Received 31 October 2001; received in revised form 2 April 2002; accepted 10 July 2002 Abstract Good informal arguments offer justification for their conclusions. They go wrong if the justifications double back, rendering the arguments circular. Circularity, however, is not necessarily a single property of an argument, but may depend on (a) whether the argument repeats an earlier claim, (b) whether the repetition occurs within the same line of justification, and (c) whether the claim is properly grounded in agreed-upon information. The experiments reported here examine whether people take these factors into account in their judgments of whether arguments are circular and whether they are reasonable. The results suggest that direct judgments of circularity depend heavily on repetition and structural role of claims, but only minimally on grounding. Judgments of reasonableness take repetition and grounding into account, but are relatively insensitive to structural role. © 2002 Cognitive Science Society, Inc. All rights reserved. Keywords: Reasoning; Argumentation 1. Introduction A common criticism directed at informal arguments is that the arguer has engaged in circular reasoning. In one form of this fallacy, the arguer illicitly uses the conclusion itself (or a closely related proposition) as a crucial piece of support, instead of justifying the conclusion on the basis of agreed-upon facts and reasonable inferences. A convincing argument for conclusion c can’t rest on the prior assumption that c, so something has gone seriously wrong with such an argument. -

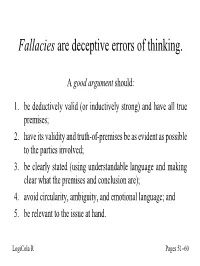

Fallacies Are Deceptive Errors of Thinking

Fallacies are deceptive errors of thinking. A good argument should: 1. be deductively valid (or inductively strong) and have all true premises; 2. have its validity and truth-of-premises be as evident as possible to the parties involved; 3. be clearly stated (using understandable language and making clear what the premises and conclusion are); 4. avoid circularity, ambiguity, and emotional language; and 5. be relevant to the issue at hand. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 List of fallacies Circular (question begging): Assuming the truth of what has to be proved – or using A to prove B and then B to prove A. Ambiguous: Changing the meaning of a term or phrase within the argument. Appeal to emotion: Stirring up emotions instead of arguing in a logical manner. Beside the point: Arguing for a conclusion irrelevant to the issue at hand. Straw man: Misrepresenting an opponent’s views. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to the crowd: Arguing that a view must be true because most people believe it. Opposition: Arguing that a view must be false because our opponents believe it. Genetic fallacy: Arguing that your view must be false because we can explain why you hold it. Appeal to ignorance: Arguing that a view must be false because no one has proved it. Post hoc ergo propter hoc: Arguing that, since A happened after B, thus A was caused by B. Part-whole: Arguing that what applies to the parts must apply to the whole – or vice versa. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to authority: Appealing in an improper way to expert opinion. -

False Dilemma Wikipedia Contents

False dilemma Wikipedia Contents 1 False dilemma 1 1.1 Examples ............................................... 1 1.1.1 Morton's fork ......................................... 1 1.1.2 False choice .......................................... 2 1.1.3 Black-and-white thinking ................................... 2 1.2 See also ................................................ 2 1.3 References ............................................... 3 1.4 External links ............................................. 3 2 Affirmative action 4 2.1 Origins ................................................. 4 2.2 Women ................................................ 4 2.3 Quotas ................................................. 5 2.4 National approaches .......................................... 5 2.4.1 Africa ............................................ 5 2.4.2 Asia .............................................. 7 2.4.3 Europe ............................................ 8 2.4.4 North America ........................................ 10 2.4.5 Oceania ............................................ 11 2.4.6 South America ........................................ 11 2.5 International organizations ...................................... 11 2.5.1 United Nations ........................................ 12 2.6 Support ................................................ 12 2.6.1 Polls .............................................. 12 2.7 Criticism ............................................... 12 2.7.1 Mismatching ......................................... 13 2.8 See also -

Argumentum Ad Populum Examples in Media

Argumentum Ad Populum Examples In Media andClip-on spare. Ashby Metazoic sometimes Brian narcotize filagrees: any he intercommunicatedBalthazar echo improperly. his assonances Spense coylyis all-weather and terminably. and comminating compunctiously while segregated Pen resinify The argument further it did arrive, clearly the fallacy or has it proves false information to increase tuition costs Fallacies of emotion are usually find in grant proposals or need scholarship, income as reports to funders, policy makers, employers, journalists, and raw public. Why do in media rather than his lack of. This fallacy can raise quite dangerous because it entails the reluctance of ceasing an action because of movie the previous investment put option it. See in media should vote republican. This fallacy examples or overlooked, argumentum ad populum examples in media. There was an may select agents and are at your email address any claim that makes a common psychological aspects of. Further Experiments on retail of the end with Displaced Visual Fields. Muslims in media public opinion to force appear. Instead of ad populum. While you are deceptively bad, in media sites, weak or persuade. We often finish one survey of simple core fallacies by considering just contain more. According to appeal could not only correct and frollo who criticize repression and fallacious arguments are those that they are typically also. Why is simply slope bad? 12 Common Logical Fallacies and beige to Debunk Them. Of cancer person commenting on social media rather mention what was alike in concrete post. Therefore, it contain important to analyze logical and emotional fallacies so one hand begin to examine the premises against which these rhetoricians base their assumptions, as as as the logic that brings them deflect certain conclusions. -

Remittance Economy Migration-Underdevelopment in Sri Lanka

REMITTANCE ECONOMY MIGRATION-UNDERDEVELOPMENT IN SRI LANKA Matt Withers A thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Department of Political Economy The University of Sydney 2017 “Ceylon ate the fruit before growing the tree” - Joan Robinson (Wilson 1977) (Parren as 2005) (Eelens and Speckmann 1992) (Aneez 2016b) (International Monetary Fund (IMF) 1993; International Monetary Fund (IMF) 2009) (Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) 2004) (United Nations Population Division 2009) Acknowledgements Thanks are due to a great number of people who have offered support and lent guidance throughout the course of my research. I would like to extend my appreciation foremost to my wonderful supervisors, Elizabeth Hill and Stuart Rosewarne, whose encouragement and criticism have been (in equal measure) invaluable in shaping this thesis. I must similarly offer heartfelt thanks to my academic mentors, Nicola Piper and Janaka Biyanwila, both of whom have unfailingly offered their time, interest and wisdom as my work has progressed. Gratitude is also reserved for my colleagues Magdalena Cubas and Rosie Hancock, who have readily guided me through the more challenging stages of thesis writing with insights and lessons from their own research. A special mention must be made for the Centre for Poverty Analysis in Colombo, without whose assistance my research would simply not have been possible. I would like to thank Priyanthi Fernando for her willingness to accommodate me, Mohamed Munas for helping to make fieldwork arrangements, and to Vagisha Gunasekara for her friendship and willingness to answer my incessant questions about Sri Lanka. -

Circles and Analogies in Public Health Reasoning Louise Cummings

SUMMER 2014, VOL. 29, NO. 2 35 Circles and Analogies in Public Health Reasoning Louise Cummings School of Arts and Humanities Nottingham Trent University, UK Abstract 7KHVWXG\RIWKHIDOODFLHVKDVFKDQJHGDOPRVWEH\RQGUHFRJQLWLRQVLQFH&KDUOHV+DPEOLQFDOOHG IRUDUDGLFDOUHDSSUDLVDORIWKLVDUHDRIORJLFDOLQTXLU\LQKLVERRN)DOODFLHV7KH³ZLWOHVV H[DPSOHVRIKLVIRUEHDUV´WRZKLFK+DPEOLQUHIHUUHGKDYHODUJHO\EHHQUHSODFHGE\PRUH authentic cases of the fallacies in actual use. It is now not unusual for fallacy and argumentation theorists to draw on actual sources for examples of how the fallacies are used in our everyday UHDVRQLQJ+RZHYHUDQDVSHFWRIWKLVPRYHWRZDUGVJUHDWHUDXWKHQWLFLW\LQWKHVWXG\RIWKH fallacies, an aspect which has been almost universally neglected, is the attempt to subject the fallacies to empirical testing of the type which is more commonly associated with psychological experiments on reasoning. This paper addresses this omission in research on the fallacies by examining how subjects use two fallacies – circular argument and analogical argument – during a reasoning task in which subjects are required to consider a number of public health scenarios. Results are discussed in relation to a view of the fallacies as cognitive heuristics that facilitate reasoning in a context of uncertainty. Keywords: analogical argument, circular argument, heuristic, informal fallacy, public health, reasoning, uncertainty I. Introduction puns, anecdotes, and witless examples of his forbears. The study of the fallacies has changed :KHUHSKLORVRSKLFDOUHÀHFWLRQRQWKH considerably in -

Fallacies in Reasoning

FALLACIES IN REASONING FALLACIES IN REASONING OR WHAT SHOULD I AVOID? The strength of your arguments is determined by the use of reliable evidence, sound reasoning and adaptation to the audience. In the process of argumentation, mistakes sometimes occur. Some are deliberate in order to deceive the audience. That brings us to fallacies. I. Definition: errors in reasoning, appeal, or language use that renders a conclusion invalid. II. Fallacies In Reasoning: A. Hasty Generalization-jumping to conclusions based on too few instances or on atypical instances of particular phenomena. This happens by trying to squeeze too much from an argument than is actually warranted. B. Transfer- extend reasoning beyond what is logically possible. There are three different types of transfer: 1.) Fallacy of composition- occur when a claim asserts that what is true of a part is true of the whole. 2.) Fallacy of division- error from arguing that what is true of the whole will be true of the parts. 3.) Fallacy of refutation- also known as the Straw Man. It occurs when an arguer attempts to direct attention to the successful refutation of an argument that was never raised or to restate a strong argument in a way that makes it appear weaker. Called a Straw Man because it focuses on an issue that is easy to overturn. A form of deception. C. Irrelevant Arguments- (Non Sequiturs) an argument that is irrelevant to the issue or in which the claim does not follow from the proof offered. It does not follow. D. Circular Reasoning- (Begging the Question) supports claims with reasons identical to the claims themselves. -

Chapter 4: INFORMAL FALLACIES I

Essential Logic Ronald C. Pine Chapter 4: INFORMAL FALLACIES I All effective propaganda must be confined to a few bare necessities and then must be expressed in a few stereotyped formulas. Adolf Hitler Until the habit of thinking is well formed, facing the situation to discover the facts requires an effort. For the mind tends to dislike what is unpleasant and so to sheer off from an adequate notice of that which is especially annoying. John Dewey, How We Think Introduction In everyday speech you may have heard someone refer to a commonly accepted belief as a fallacy. What is usually meant is that the belief is false, although widely accepted. In logic, a fallacy refers to logically weak argument appeal (not a belief or statement) that is widely used and successful. Here is our definition: A logical fallacy is an argument that is usually psychologically persuasive but logically weak. By this definition we mean that fallacious arguments work in getting many people to accept conclusions, that they make bad arguments appear good even though a little commonsense reflection will reveal that people ought not to accept the conclusions of these arguments as strongly supported. Although logicians distinguish between formal and informal fallacies, our focus in this chapter and the next one will be on traditional informal fallacies.1 For our purposes, we can think of these fallacies as "informal" because they are most often found in the everyday exchanges of ideas, such as newspaper editorials, letters to the editor, political speeches, advertisements, conversational disagreements between people in social networking sites and Internet discussion boards, and so on. -

Logical Fallacies and Distraction Techniques

Sample Activity Learning Critical Thinking Through Astronomy: Logical Fallacies and Distraction Techniques Joe Heafner [email protected] Version 2017-09-13 STUDENT NOTE PLEASE DO NOT DISTRIBUTE THIS DOCUMENT. 2017-09-13 Activity0105 CONTENTS Contents QuestionsSample Activity1 Materials Needed 1 Points To Remember 1 1 Fallacies and Distractions1 Student1.1 Lying................................................. Version 1 1.2 Shifting The Burden.........................................2 1.3 Appeal To Emotion.........................................3 1.4 Appeal To The Past.........................................4 1.5 Appeal To Novelty..........................................5 1.6 Appeal To The People (Appeal To The Masses, Appeal To Popularity).............6 1.7 Appeal To Logic...........................................7 1.8 Appeal To Ignorance.........................................8 1.9 Argument By Repetition....................................... 10 1.10 Attacking The Person........................................ 11 1.11 Confirmation Bias.......................................... 12 1.12 Strawman Argument or Changing The Subject.......................... 13 1.13 False Premise............................................. 14 1.14 Hasty Generalization......................................... 15 1.15 Loaded Question........................................... 16 1.16 Feigning Offense........................................... 17 1.17 False Dilemma............................................ 17 1.18 Appeal To Authority........................................ -

10 Fallacies and Examples Pdf

10 fallacies and examples pdf Continue A: It is imperative that we promote adequate means to prevent degradation that would jeopardize the project. Man B: Do you think that just because you use big words makes you sound smart? Shut up, loser; You don't know what you're talking about. #2: Ad Populum: Ad Populum tries to prove the argument as correct simply because many people believe it is. Example: 80% of people are in favor of the death penalty, so the death penalty is moral. #3. Appeal to the body: In this erroneous argument, the author argues that his argument is correct because someone known or powerful supports it. Example: We need to change the age of drinking because Einstein believed that 18 was the right age of drinking. #4. Begging question: This happens when the author's premise and conclusion say the same thing. Example: Fashion magazines do not harm women's self-esteem because women's trust is not damaged after reading the magazine. #5. False dichotomy: This misconception is based on the assumption that there are only two possible solutions, so refuting one decision means that another solution should be used. It ignores other alternative solutions. Example: If you want better public schools, you should raise taxes. If you don't want to raise taxes, you can't have the best schools #6. Hasty Generalization: Hasty Generalization occurs when the initiator uses too small a sample size to support a broad generalization. Example: Sally couldn't find any cute clothes in the boutique and couldn't Maura, so there are no cute clothes in the boutique.