From Cars to Planes and Back Again, Part Three by Andre Swygert the First Two Articles in This Series About Automobile Manufactu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ford Tri-Motor Design

1003cent.qxd 9/12/03 10:11 AM Page 1 he Ford Tri-Motor design was Liberty engines during World War I, Tone of the most successful early Stout was employed by the govern- transports. Nicknamed the Tin ment to build an all-metal single- Goose, it was one of the largest all- wing torpedo bomber. Using the metal aircraft built in America up to knowledge he learned during this that time. It featured corrugated alu- project, he founded the Stout Metal minum covering on the fuselage, Airplane Company, with a focus on wings, tail, and on the internally building civil aircraft of composite braced cantilever wing. The Ford metal and wood construction. Tri-motor was an inherently stable Many factors drove metal con- airplane, designed to fly well on two struction. Maintenance accounted engines and to maintain level flight for a large portion of an aircraft’s di- on one. The first three Tri-Motors rect operating cost. In particular, built seated the pilot in an open Ford’s fabric needed regular replacement cockpit, as many pilots doubted that after every 750 to 1000 flying hours. a plane could be flown without the Eliminating the periodic replace- direct “feel of the wind.” Tri-Motor ment of fabric offset the increased Henry Ford is credited with cost of metal aircraft coverings. founding American commercial The Ford Tri-Motor, Ford supported Stout’s ideas by aviation when the Ford Freight building an airplane factory with a Service, comprising six aircraft, affectionately known as the landing field, and leasing it to the began flying between Chicago and “Tin Goose,” was the Stout Metal Airplane Company. -

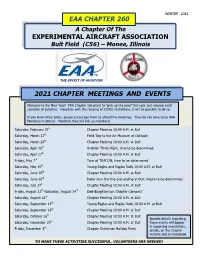

Eaa Chapter 260

WINTER 2021 EAA CHAPTER 260 A Chapter Of The EXPERIMENTAL AIRCRAFT ASSOCIATION Bult Field (C56) – Monee, Illinois THE SPIRIT OF AVIATION 2021 CHAPTER MEETINGS AND EVENTS Welcome to the New Year! EAA Chapter 260 plans to “pick up the pace” this year and resume a full schedule of activities. Hopefully with the relaxing of COVID restrictions, it will be possible to do so. If you know other pilots, please encourage them to attend the meetings. They do not have to be EAA Members to attend. Hopefully they will join as members! Saturday, February 20th Chapter Meeting 10:00 A.M. at Bult Saturday, March 13th Field Trip to the Air Museum at Oshkosh Saturd ay, March 20th Chapter Meeting 10:00 A.M. at Bult th Saturd ay, April 10 Aviation Trivia Night, time to be determined Saturday, April 17th Chapter Meeting 10:00 A.M. at Bult Friday, May 7th Tour of TRACON, time to be determined Saturd ay, May 15th Young Eagles and Eagles Rally 10:00 A.M. at Bult th Saturd ay, June 19 Chapter Meeting 10:00 A.M. at Bult Saturday, June 26th Poker Run Starting and ending at Bult. Route to be determined Saturday, July 17th Chapter Meeting 10:00 A.M. at Bult Friday, August 13th–Saturday, August 14th Dad-daughter/son Chapter Campout st Saturd ay, August 21 Chapter Meeting 10:00 A.M. at Bult Saturday, September 11th Young Eagles and Eagles Rally 10:00 A.M. at Bult Saturday, September 18th Chapter Meeting 10:00 A.M. at Bult Saturd ay, October 16th Chapter Meeting 10:00 A.M. -

Research Center New and Unprocessed Archival Accessions

NEW AND UNPROCESSED ARCHIVAL ACCESSIONS List Published: April 2020 Benson Ford Research Center The Henry Ford 20900 Oakwood Boulevard ∙ Dearborn, MI 48124-5029 USA [email protected] ∙ www.thehenryford.org New and Unprocessed Archival Accessions April 2020 OVERVIEW The Benson Ford Research Center, home to the Archives of The Henry Ford, holds more than 3000 individual collections, or accessions. Many of these accessions remain partially or completely unprocessed and do not have detailed finding aids. In order to provide a measure of insight into these materials, the Archives has assembled this listing of new and unprocessed accessions. Accessions are listed alphabetically by title in two groups: New Accessions contains materials acquired 2018-2020, and Accessions 1929-2017 contains materials acquired since the opening of The Henry Ford in 1929 through 2017. The list will be updated periodically to include new acquisitions and remove those that have been more fully described. Researchers interested in access to any of the collections listed here should contact Benson Ford Research Center staff (email: [email protected]) to discuss collection availability. ACCESSION NUMBERS Each accession is assigned a unique identification number, or accession number. These are generally multi-part codes, with the left-most digits indicating the year in which the accession was acquired by the Archives. There, are however, some exceptions. Numbering practices covering the majority of accessions are outlined below. - Acquisitions made during or after the year 2000 have 4-digit year values, such as 2020, 2019, etc. - Acquisitions made prior to the year 2000 have 2-digit year values, such as 99 for 1999, 57 for 1957, and so forth. -

Ford Trimotor

Ford Trimotor The Ford Trimotor (also called the “Tri-Motor”, and The Ford Trimotor using all-metal construction was not a nicknamed “The Tin Goose”) was an American three- revolutionary concept, but it was certainly more advanced engined transport aircraft. Production started in 1925 by than the standard construction techniques of the 1920s. the companies of Henry Ford and until June 7, 1933. A The aircraft resembled the Fokker F.VII Trimotor (ex- total of 199 Ford Trimotors were made.[1] It was designed cept for being all-metal which Henry Ford to claimed for the civil aviation market, but also saw service with made it “the safest airliner around”).[3] Its fuselage and military units. The Ford Trimotor was sold around the wings followed a design pioneered by Junkers[4] during world. World War I with the Junkers J.I and used postwar in a series of airliners starting with the Junkers F.13 low- wing monoplane of 1920 of which a number were ex- 1 Design and development ported to the US, the Junkers K 16 high-wing airliner of 1921, and the Junkers G 24 trimotor of 1924. All of these were constructed of aluminum alloy, which was corrugated for added stiffness, although the resulting drag reduced its overall performance.[5] So similar were the designs that Junkers sued and won when Ford attempted to export an aircraft to Europe.[6] In 1930, Ford counter- sued in Prague, and despite the possibility of anti-German sentiment, was decisively defeated a second time, with the court finding that Ford had infringed upon Junkers’ patents.[6] Although designed primarily for passenger use, the Tri- motor could be easily adapted for hauling cargo, since its seats in the fuselage could be removed. -

FORD TRI-MOTOR HOMECOMING RECORDS, 1955-1958 Accession 613

Finding Aid for FORD TRI-MOTOR HOMECOMING RECORDS, 1955-1958 Accession 613 Finding Aid Published: October 2011 Electronic conversion of this finding aid was funded by a grant from the Detroit Area Library Network (DALNET) http://www.dalnet.lib.mi.us 20900 Oakwood Boulevard ∙ Dearborn, MI 48124-5029 USA [email protected] ∙ www.thehenryford.org Ford Tri-Motor homecoming records Accession 613 OVERVIEW REPOSITORY: Benson Ford Research Center The Henry Ford 20900 Oakwood Blvd Dearborn, MI 48124-5029 www.thehenryford.org [email protected] ACCESSION NUMBER: 613 CREATOR: Ford Motor Company. Office of Public Relations. TITLE: Ford Tri-Motor homecoming records INCLUSIVE DATES: 1955-1958 QUANTITY: 0.8 cubic ft. LANGUAGE: The materials are in English ABSTRACT: The Ford Tri-Motor airplane was produced in 1927 by the Stout Metal Airplane Company, owned by Henry Ford. In 1955 an anniversary celebration was held for the aircraft and in 1958 it was commemorated again with a historical marker in Dearborn. This collection includes photographs, correspondence, clippings and programs from these two events. Page 2 of 5 Ford Tri-Motor homecoming records Accession 613 ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION ACCESS RESTRICTIONS: The collection is open for research COPYRIGHT: Copyright has been transferred to The Henry Ford by the donor. Copyright for some items in the collection may still be held by their respective creator(s). ACQUISITION: Ford Motor Company Archives donation, 1964 RELATED MATERIAL: Related material held by The Henry Ford - Stout Metal Airplane Division records subseries, 1920- 1942, Accession 18, 251 and 383. PREFERRED CITATION: Item, folder, box, accession 613, Ford Tri-Motor homecoming records, Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford PROCESSING INFORMATION: Collection processed by Ford Motor Company Archives staff, May 1964. -

Lw.924.....· ...1.M93~2,-- # 'M Record

7(1«) JlmORC.,.lIIUCBma S!otrrwrJIi ..lllPUD C~An DlSCRlP1'IOR or !HI IICCIrIS ACCESSION 18 ¥g.ep_'PTIIIL""h£~c~hIllH~_,~QnIuriJiI.~~!",,!,,", ~.~_.~. -_~o ~9io129l1ii1.~ -.~.JIoii:096""-~_~_~ ... .... _. ..... __ ....l!I#r* r'D R.cOl'ds ot orderl placed with TeDders. the'tout "tal J.1rp1ue .. - ... ~ - c~ tor parts .. _tArials.. fhq are tUed :lD ...r1cal m.r with the hiBheat _'bert. the tront ot each tolder. OIders were - . not :l.sna.d 1a ....rical ••quelice theret..e do not toll_ a striot chronological order. Thea. orden are .erl•• ~ oil ·'10026 .. Q 19800 - 98'00. !hls Parch... Order tUe o.priles orde~1 trOll 'OM airplane oner. tor part. and a.nioe. t. be tarni.hed lIT the.St. Mltal J.1rp1ane C~UV', oontaini"l the pvohue or4er, correspcmde.e ad other aupporting dooumeDt...AftupmeDt·18 alphabetical • cutau.. lIaJIe. There 11 no oenaei.t.1It .ethod ot arrugeJn.at vith1Dea. tolder 'but genera111 the lateet .-del' il to the tront ot each t11e. These purcha.e orders a.prise orders tor parts aDd aenices trom custamerl other than Pord airplane CIW118rl. ArraDged chronololicl1l7 by year. Belated d~eJltl aDd correspondence are tiled with the parch..e OJ'der. &V.:.:B~, ...:;Mp..,;:o_.........=br.lOj.:u'loZ.',-=r..::l~IIIIi'iI.:..- --=lw.924.....·_...1.M93~2,-- # 'm Record. trClll the otf'1ce .t V. B. JllTo, Tice ~81deDt ot Stoat Mltl1 Airplane CompalV and EXecutive Director of all aviation operations in the Ford Motor aompaui~ 1925 - ~932. They are arranged alphabetically b7 subject headiDg. -

The Mighty Ford Trimotor: Helping to Forge a Global Aviation System on June 11, 1926, the Ford Trimotor Made Its First Flight

The Mighty Ford Trimotor: Helping to Forge a Global Aviation System On June 11, 1926, the Ford Trimotor made its first flight. The plane, produced by the Ford Motor Company, and designed by William Bushnell Stout, revolutionized air transportation around the world. The Trimotor, one of the first all-metal airplanes, was the first plane built to carry passengers rather the mail. The original 4-AT model seated eight passengers, later increased to twelve, and then thirteen passengers. The plane had three engines, which allowed it to fly higher and faster than other airplanes of the same time period. It could reach speeds up to 150 miles per hour. The plane, affectionately called the Tin Goose or the Flying Washboard, proved exceptionally reliable, able to land safely with just one of its three engines. The nicknames apparently reflected the plane’s attributes. Flying Washboard because of its corrugated external body. Tin Goose, perhaps because many called Ford’s Model T car, the Tin Lizzie. Writer Larry Janoff offers another explanation for the name: “it ‘waddled’ down the runway like a goose and the three loud engines could sound like a goose honking.” Ford, like other automobile companies, entered the aviation business during World War I, building Liberty engines. After the war, it returned to auto manufacturing until 1925. That year, Henry Ford acquired the Stout Metal Airplane Company for an estimated $1 million. In announcing his purchase on August 6, Henry Ford remarked, “The first thing that must be done with aerial navigation is make it fool-proof . What the Ford Motor Company means to do is prove whether commercial flying can be done safely and profitably.” Ford remarked that he had never been in the air and had no desire to fly. -

DICKINSON COUNTY HISTORY – TRANSPORTATION – AIRPLANES [Compiled & Transcribed by William J

DICKINSON COUNTY HISTORY – TRANSPORTATION – AIRPLANES [Compiled & Transcribed by William J. Cummings] EARLY AIR EAGLE WILL SCREAM TRANSPORTATION _____ Iron Mountain Press, Iron Mountain, Iron Mountain Is Planning Dickinson County, Michigan, Volume 17, Biggest Celebration Number 15 [Thursday, August 29, in the U.P. 1912], page 1, column 6 _____ MAY BE VISITED The call issued by Mayor Cruse for a BY AEROPLANE meeting of citizens to consider the matter of _____ a Fourth of July celebration was held at the city hall last Monday evening and was well Only Aeroplane Built in U.P. to Make attended. Maiden Flight Soon. The meeting was opened by his honor, who after stating the object of the meeting, If the Iron Mountain people should voiced a desire to make the celebration a awaken some morning and gazing upward county affair and invite Norway neighbors to see a huge, bird-like object flying over their participate in the “doings.” housetops they should neither summon A temporary organization was perfected help nor run for their shot-guns [sic – by the election of Mayor Cruse as chairman shotguns], as it will only be an aeroplane, and S. Rex Plowman performed the duties invented and constructed by E.E. Lesard, of scribe. formerly of St. Louis, machinist at the Frank M. Milliman, Henry LaFountaine Negaunee garage of Charles J.A. Forell, and John Andrews, Jr., were named a Jr. Mr. Lessard is seriously thinking of committee on permanent organization. A flying with his hydro-aeroplane in this general committee of arrangements was direction for the purpose of demonstrating named, as follows: Louis J. -

The Newsletter of the NWA History Centre Dedicated to Preserving the History of a Great Airline and Its People

Vol.14, no.3 nwahistory.org facebook.com/NWA.History.Centre September 2016 REFLECTIONS The Newsletter of the NWA History Centre Dedicated to preserving the history of a great airline and its people. NORTHWEST AIRLINES 1926-2010 ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ FOUNDING FATHERS by Robert DuBert starring LEWIS HOTCHKISS BRITTIN Director, St. Paul Association and founder of Northwest Airways WILLIAM BENSON MAYO Chief Engineer, Ford Motor Company WILLIAM BUSHNELL STOUT Founder, Stout Metal Airplane Company and President, Stout Air Lines and HENRY FORD SUPPORTING CAST Edsel Ford Eddie Stinson Bill Mara Paul Henderson James McDonnell with Charles Dickinson Edward Budd Camille Stein Robert Stranahan Frederick Rentschler and members of The Detroit Athletic Club If this were a documentary film, that's how the introduction to the screenplay might read. The founding of Northwest Airways, later to become Northwest Airlines, was not inevitable. It was the fortunate result of the individual and joint endeavors of a group of business leaders and an unfolding chain of events occuring over the span of just a few years, whose outcome no one could have predicted in advance. Some executives of the Ford Motor Company played key roles, and with events unfolding simultaneously in Detroit and the Twin Cities, it is impossible to tell this story in a strictly chronological order without some “backing and filling.” So please bear with me as I serve as your explorer, to focus on the galaxie of people whose fusion of effort gave Lewis Brittin (no country squire he) the business edge he needed to get our airline off the ground. CONNECTICUT YANKEE Lewis Hotchkiss Brittin was born in Derby, a fateful turn of events which brought him to the Twin Cities on Conn. -

Finding Aid for the Photographic Vertical File Series

Finding Aid for PHOTOGRAPHIC VERTICAL FILE SERIES, 1860-1980 (BULK 1890-1955) Accession 1660 Finding Aid Published: March 2012 Electronic conversion of this finding aid was funded by a grant from the Detroit Area Library Network (DALNET) http://www.dalnet.lib.mi.us Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford 20900 Oakwood Boulevard ∙ Dearborn, MI 48124-5029 USA [email protected] ∙ www.thehenryford.org Ford Motor Company photographs collection Archives (Ford Motor Company) photographs subgroup Photographic vertical file series Accession 1660 OVERVIEW REPOSITORY: Benson Ford Research Center The Henry Ford 20900 Oakwood Blvd Dearborn, MI 48124-5029 www.thehenryford.org [email protected] ACCESSION NUMBER: 1660 CREATOR: Ford Motor Company. Archives. TITLE: Photographic vertical file series INCLUSIVE DATES: 1860-1980 BULK DATES: 1890-1955 QUANTITY: 53.33 linear ft LANGUAGE: The materials are in English. ABSTRACT: The Photographic vertical file series is an assembled collection of photographs from a variety of sources. The series contains both original photographs and copy photographs, covering a wide range of topics. Page 2 of 115 Ford Motor Company photographs collection Archives (Ford Motor Company) photographs subgroup Photographic vertical file series Accession 1660 ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION ACCESS RESTRICTIONS: The collection is open for research. COPYRIGHT: Copyright has been transferred to The Henry Ford by the donor. Copyright for some items in the collection may still be held by their respective creator(s). -

Innermarker-March 2001

INNERMARKER Newsletter of the Aviation Law Section State Bar of Michigan Donald C. Frank, Editor VOLUME 9, NO. 1 www.michbar.org/sections/aviation JULY 2002 screening, airport security personnel, flight deck secu- I. General Aviation rity, and deployment of air marshals. It also establishes Security in Michigan an entirely new federal agency, the Transportation Security Administration. By: Thomas Krashen Michigan Bureau of Aeronautics GENERAL AVIATION AIRPORTS – SECURITY PLAN REQUIRED BY MAC The horrific attacks on the United States of Sep- General aviation airports and operators initially were tember 11, 2001 have had widespread effect on life in not affected by these new federal security measures. this country. Arguably, no profession or industry has However, many states have adopted a plan to include been affected as much as aviation in the aftermath of general aviation airports in security planning. In many the attacks. The response by federal and state govern- cases states taken this action in the hope that addi- ment has resulted in numerous new regulations, proce- tional federal measures would not be forthcoming. dures, and restrictions that were beyond imagination nine months ago. Indeed, it is not an exaggeration to Michigan’s approach has been to assist operators say that our industry will never be the same. of general aviation airports in adopting security plans which are appropriate for their level of activity. It is rec- AIR CARRIER AIRPORTS ognized that airports of varying size will have different Among the first responses to the terrorist attacks, security needs. was sweeping new federal legislation directed at the In November 2001 the Michigan Aeronautics nation’s air carrier airports. -

CAMP Insight JUN 2012 20Pg.Indd

p18 THE RENAISSANCE MAN OOF THE “BIG FOUR” BY GIACINTAF BRADLEY KOONTZ T H E “ B IG F O U R JUNE 2012 ” TTRAINING?WWHY GET Serving R H BY BILLA DE DECKERY the Business Aviation Community IN G I E N T G ? p4 AAMSTAT: FIRST 40 QQUARTERM NEW Since 1968 + S U T A A R T DDELIVERIEST : E E F L R I BY JUDYI NERWINSKI R V N S E E T R W p7 IE S CaCatctch UpUp Witith CACAMPMP – SeSee yoyou atat thehesese cononfefererencnceess – Upcoming:UpU p co SEESES BACK COVER FOR DETAILS o E SSeminarCAMPC mim BAB e ingn A A g CKC m M : K Nashville,NaN TN C a JulyJ 24in P OVO shs u V h l a ERE y r R vivi F lll 2 ORO le,e 4 D T ETE N TAIA LSL S CAMP DIRECTORY | www.CAMPSYSTEMS.com (West continued) (International continued) (WebECTM continued) Contents LOCATIONS Tom Ritrovato, West RSM George Rossides, International RSM Tel: 631-588-3200 ext. 239 NORTH AMERICA Tel (direct): 603-821-6430 Tel: 631-588-3200 ext. 212 Efax: 1-800-521-9109 Greetings New York (Headquarters) Toll Free: 1-800-558-6327 Toll Free: 1-877-411-2267 Toll Free: 1-877-411-2267 ext. 239 Camp Systems International Inc. E: [email protected] E: [email protected] E: [email protected] 04 INDUSTRY INSIGHTS LI MacArthur Airport Why Get Training? 999 Marconi Avenue North Central (IL, IN, IA, KY, MI, OEM BASED WebECTM SUPPORT June greetings, positioned By Bill de Decker Ronkonkoma, NY 11779 USA MN, MO, NE, ND, OH, SD, WV, WI) Wichita 375 Roland-Th errien, Suite 140 across fi ve Have you been strategizing about Eli Stepp, Jr., HBC / Cessna Field Service Rep Longueuil, QC J4H 4A6 Tel: 631-588-3200 regions of North Central Regional FSR Th omas Williams Canada 07 AMSTAT MARKET ANALYSIS how you can work more effi ciently since Fax: 631-588-3294 the U.S., and Mobile: 217-801-3701 CAMP Systems International Inc.