University of Cincinnati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dec. 22, 2015 Snd. Tech. Album Arch

SOUND TECHNIQUES RECORDING ARCHIVE (Albums recorded and mixed complete as well as partial mixes and overdubs where noted) Affinity-Affinity S=Trident Studio SOHO, London. (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) R=1970 (Vertigo) E=Frank Owen, Robin Geoffrey Cable P=John Anthony SOURCE=Ken Scott, Discogs, Original Album Liner Notes Albion Country Band-Battle of The Field S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Island Studio, St. Peter’s Square, London (PARTIAL TRACKING) R=1973 (Carthage) E=John Wood P=John Wood SOURCE: Original Album liner notes/Discogs Albion Dance Band-The Prospect Before Us S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. (PARTIALLY TRACKED. MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Olympic Studio #1 Studio, Barnes, London (PARTIAL TRACKING) R=Mar.1976 Rel. (Harvest) @ Sound Techniques, Olympic: Tracks 2,5,8,9 and 14 E= Victor Gamm !1 SOUND TECHNIQUES RECORDING ARCHIVE (Albums recorded and mixed complete as well as partial mixes and overdubs where noted) P=Ashley Hutchings and Simon Nicol SOURCE: Original Album liner notes/Discogs Alice Cooper-Muscle of Love S=Sunset Sound Recorders Hollywood, CA. Studio #2. (TRACKED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Record Plant, NYC, A&R Studio NY (OVERDUBS AND MIX) R=1973 (Warner Bros) E=Jack Douglas P=Jack Douglas and Jack Richardson SOURCE: Original Album liner notes, Discogs Alquin-The Mountain Queen S= De Lane Lea Studio Wembley, London (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) R= 1973 (Polydor) E= Dick Plant P= Derek Lawrence SOURCE: Original Album Liner Notes, Discogs Al Stewart-Zero She Flies S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. -

Andy Roberts Urban Cowboy 01

ANDY ROBERTS 01 URBAN COWBOY www.thebeesknees.com ANDY ROBERTS 02 URBAN COWBOY The first seeds for this album were sown in October 1970. Everyone, my Morgan Studios had been started by well-known drummer Barry Morgan post Liverpool Scene band, was put out of business in a devastating four years before, and was Samwell’s studio of choice. His principal client instant when our long wheelbase Transit was side swiped in Basingstoke in those days was Cat Stevens, who was well on his way to being a global by a jack-knifing flatbed, killing Paul Scard, our 19-year-old roadie, and superstar. One day after a Matthews session I was taking my time packing injuring Andy Rochford, his colleague. up my guitars, when in strolled Alan Davies, who was Steve’s right hand man on acoustic (still is, as far as I know). Alan and I knew each other from The musicians in the band were all safely back in London when it way back, when we had both at various times played with Jeremy Taylor happened. Earlier we had played at Southampton University, and I was and Sydney Carter. I showed him the Kriwaczek String Organ I had with Plainsong rehearsal photographs by Harry Isles sitting in drummer John Pearson’s kitchen in Bruton Place, having a cup me (a unique stringed instrument, designed by a great friend of mine, of of tea with John, Dave Richards and Paul, when Andy Rochford phoned up which I was at that time the sole exponent!), and then we began playing to ask if Paul could possibly return to Southampton to fetch him. -

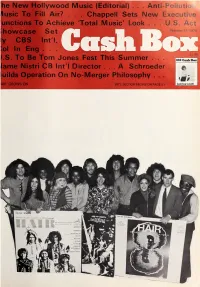

Howcas% Set February 21, 1970 '^ Ly CBS-' Int's

he New Hollywood Music (Editorial) . Anti-Pb^ yiusic To Fill Air? . , . Chappell Sets New Executive -unctions To Achieve Total Music' Look . U S. Act »howcas% Set February 21, 1970 '^ ly CBS-' Int'S ^ol In Eng . J.S. To Be Tom Jones Fest This Summer . Jame Nistri CB Int'l Director ... A. Schroeder luilds Operation On No-Merger Philosophy . lAIR' GROWS ON INT'L SECTION BEGINS ON PAGE 51 Theygot oii on ihewrongapple. And that’s where Gary Puckett and The Union Gap’s new single begins'' (Lets Give Adam and Eve) Another Chance.”A compelling rock-gospel song that ought to go all the way. And that shouldn’t be surprising. Because Gary Puckett just seems to have one hit single after another. So you don’t need too much help picking them. Gary Puckett and The Union Gap 99 (Lets GiveAdam And Eve) Another Chance (4S-45097) On Columbia Records h ® "COLUMBIA,"gMARCAS REG. PRINTED IN U.S.A. CcishBoK VOL XXXI - Number 30/February 21, 1970 Publication Office/ 1780 Broadway, New York, New York 10019 / Telephone JUdson 6-2640/Cable Address: Cash Box, N Y, GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher MARTY OSTROW Vice President IRV LICHTMAN Editor in Chief EDITORIAL MARV GOODMAN Assoc. Editor ALLAN RINDE West Coast Editor JOHN KLEIN NORMAN STEINBERG ED KELLEHER EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS MIKE MARTUCCI ANTHONY LANZETTA ADVERTISING EERNIE BLAKE Director of Advertising The ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES New STAN SOIFER, New York HARVEY GELLER, Hollywood WOODY HARDING Art Director COIN MACHINE & VENDING Hollywood Music ED ADLUM General Manager BOB COHEN, Assistant CAMILLE COMPASIO, Chicago LISSA MORROW, Hollywood CIRCULATION THERESA TORTOSA, Mgr. -

Lps Page 1 -.:: GEOCITIES.Ws

LPs ARTIST TITLE LABEL COVER RECORD PRICE 10 CC SHEET MUSIC UK M M 5 2 LUTES MUSIC IN THE WORLD OF ISLAM TANGENT M M 10 25 YEARS OF ROYAL AT LONDON PALLADIUM GF C RICHARD +E PYE 2LPS 1973 M EX 20 VARIETY JOHN+SHADOWS 4 INSTANTS DISCOTHEQUE SOCITY EX- EX 20 4TH IRISH FOLK FESTIVAL ON THE ROAD 2LP GERMANY GF INTRERCORD EX M 10 5 FOLKFESTIVAL AUF DER LENZBURG SWISS CLEVES M M 15 5 PENNY PIECE BOTH SIDES OF 5 PENNY EMI M M 7 5 ROYALES LAUNDROMAT BLUES USA REISSUE APOLLO M M 7 5 TH DIMENSION REFLECTION NEW ZEALAND SBLL 6065 EX EX 6 5TH DIMENSION EARTHBOUND ABC M M 10 5TH DIMENSION AGE OF AQUARIUS LIBERTY M M 12 5TH DIMENSION PORTRAIT BELL EX EX- 5 75 YEARS OF EMI -A VOICE WITH PINK FLOYD 2LPS BOX SET EMI EMS SP 75 M M 40 TO remember A AUSTR MUSICS FROM HOLY GROUND LIM ED NO 25 HG 113 M M 35 A BAND CALLED O OASIS EPIC M M 6 A C D C BACK IN BLACK INNER K 50735 M NM 10 A C D C HIGHWAY TO HELL K 50628 M NM 10 A D 33 SAME RELIGIOUS FOLK GOOD FEMALE ERASE NM NM 25 VOCALS A DEMODISC FOR STEREO A GREAT TRACK BY MIKE VICKERS ORGAN EXP70 M M 25 SOUND DANCER A FEAST OF IRISH FOLK SAME IRISH PRESS POLYDOR EX M 5 A J WEBBER SAME ANCHOR M M 7 A PEACOCK P BLEY DUEL UNITY FREEDOM EX M 20 A PINCH OF SALT WITH SHIRLEY COLLINS 1960 HMV NM NM 35 A PINCH OF SALT SAME S COLLINS HMV EX EX 30 A PROSPECT OF SCOTLAND SAME TOPIC M M 5 A SONG WRITING TEAM NOT FOR SALE LP FOR YOUR EYES ONLY PRIVATE M M 15 A T WELLS SINGING SO ALONE PRIVATE YPRX 2246 M M 20 A TASTE OF TYKE UGH MAGNUM EX EX 12 A TASTE OF TYKE SAME MAGNUM VG+ VG+ 8 ABBA GREATEST HITS FRANCE VG 405 EX EX -

Full Programme As

Notes Contents Contents 1 Abstracts (Alphabetically by Presenter) 4-20 Programme (Friday) 22-24 Programme (Saturday) 25-28 Programme (Sunday) 29-32 Underdog - THE AFTER PARTY - All Days 33 Films 34-35 Performers 37 Speaker Bios 38-46 Artists Bios 47-48 Sponsors 52 Contributors 53 Media Partners 53 Acknowledgements 50-51 University Map 55 Venue Map 56 General Info 57 Notes 57-60 Break Times Friday Saturday & Sunday 11:00 - 11:30 Break 11:00 - 11:30 Break 13:30 - 14:30 Lunch 13:00 - 14:30 Lunch Artwork: maze & brain logos by Blue Firth, front cover by Judith Way, inside back cover 16:30 - 17:00 Break 16:30 - 17:00 Break by Cameron Adams, back cover background by Dave King, booklet design and layout Giorgos Mitropapas Programme Design by Giorgos Mitropapas - www.gmitropapas.com 60 1 Notes 2 59 General Info Transport There is transport info on the website http://breakingconvention.co.uk/location/ and London transport info is available from http://www.t! .gov.uk Catering Regrettably there are no refreshments available in the conference centre during the weekend but you can bring your own and there are numerous cafés around outside the university within easy walking distance (5-10 mins) and we have reasonably long breaks. The university refectory is also open in the adjacent building (Queen Mary) and is serving cold snacks/meals and hot/cold drinks, but on Saturday & Sunday only! If you are a tea or co" ee addict, like me, you might consider bringing a ! ask of the black stu" to keep your blood-ca" eine levels high or be prepared for a small stroll to get your # x. -

Goldenjubilee Entomologist.Pdf (3.369Mb)

Golden Jubilee 1959- 50 years -2009 The Virginia Tech ENTOMOLOGIST m part en e t o D f h E c n e t o T m a i o n i l o g g r i y V 50 1 9 959-200 Dedicated to the memory of our rst Department Head James McDonald Grayson “Eulogy for Daddy” delivered by Nancy L. Grayson, March 10, 2008 On behalf of my sisters, our mother, and the rest of our family, I want to thank you – each of you – for being here with us today to celebrate the life of a man who was incredibly dear to us and, I suspect, most of you as well. So many people have come up to us in recent years to tell us how much they admired and appreciated daddy. They’ve recounted wonderful stories that we’ve loved hearing. Almost invariably, what has come through most strongly in these stories and memories is his deep integrity, his fairness in dealing with people, and his lack of pretension. Daddy really did value people for their character and accomplishments, not for their looks or their money or their social standing. He didn’t have much truck with people who put on airs or thought overly well of themselves. He had a particularly fine sense of proportion regarding life’s values and priorities that stemmed in part, I think, from his upbringing in the mountains of Southwest Virginia. Daddy grew up on a farm near Austinville in Wythe County and, for the first eight grades, went to school in a one-room schoolhouse. -

Cynthia Begin Forwarded Message: From: Will Meeks <Will Meeks@Fws

From: Cynthia Martinez To: D M Ashe; [email protected]; Jim Kurth; Betsy Hildebrandt; Matt Huggler; [email protected] Subject: Fwd: Complete turnover of the National Bison Range to a special interest group and in violation of every federal law that started and protects the National Wildlife Refuge System. Date: Sunday, February 07, 2016 4:51:08 PM Cynthia Begin forwarded message: From: Will Meeks <[email protected]> Date: February 7, 2016 at 4:46:13 PM EST To: Anna Munoz <[email protected]>, Cynthia Martinez <[email protected]> Subject: Fwd: Complete turnover of the National Bison Range to a special interest group and in violation of every federal law that started and protects the National Wildlife Refuge System. Will Meeks U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Mountain-Prairie Region Assistant Regional Director National Wildlife Refuge System 303-236-4303(w) 720-541-0319 (c) Begin forwarded message: From: Jeff King <[email protected]> Date: February 7, 2016 at 2:04:49 PM MST To: Noreen Walsh <[email protected]>, Will Meeks <[email protected]>, Mike Blenden <[email protected]>, Matt Hogan <[email protected]> Subject: Fwd: Complete turnover of the National Bison Range to a special interest group and in violation of every federal law that started and protects the National Wildlife Refuge System. Thanks jk Sent from my iPhone Begin forwarded message: From: Susan Reneau <[email protected]> Date: February 7, 2016 at 1:56:59 PM MST To: <[email protected]> Subject: Complete turnover of the National Bison Range to a special interest group and in violation of every federal law that started and protects the National Wildlife Refuge System. -

Flyer News, Vol. 62, No. 22

TUESDAY, MARCH 24, 2015 NEWS // Rumors of dramatic hous- A&E // Student band Funny Business OPINIONS // Student responds to on- SPORTS // Sooners outlast Flyers VOL. 62 NO. 22 ing changes are dispelled by residence explores different genres, takes to re- campus police mistreatment, pg. 11. in Round of 32, pg. 16. official, pg. 6. cording studio, pg. 7. Bridget Corrigan and Kristin Ackerman participate in Zeta Tau Alpha’s Car Smash for FLYER NEWS breast cancer awareness. Martin Sheen Flyers get first taste of Sweet 16 to receive STEVE MILLER honorary Asst. Sports Editor UD degree “The goal all along has been the Sweet Sixteen,” head coach Jim Jabir RACHEL CAIN reminded the UD women’s basketball Staff Writer team before their second-round game against the University of Kentucky on Sunday. Hollywood actor and social ac- Consider the mission accomplished. tivist Martin Sheen will join the Overcoming foul trouble with stel- class of 2015 at commencement lar free-throw and three-point per- May 3 where he will receive an centages, the seventh-seeded Flyers honorary degree for a lifetime knocked off second-seeded Kentucky commitment to social justice, ac- in the most monumental game in Day- cording to a University of Dayton ton women’s basketball history thus press release. f a r. Sheen, a practicing Roman This marks the first time in pro- Catholic, has earned fame for his gram history that the women’s team performances on stage, in films has advanced to the Sweet Sixteen. It and on television. In an acting was the sixth straight year, however, career spanning nearly 50 years, that UD appeared in the NCAA wom- Sheen has become best known en’s basketball tournament. -

An Investigation Into Subtitling in French and Spanish Heritage Cinema

AN INVESTIGATION INTO SUBTITLING IN FRENCH AND SPANISH HERITAGE CINEMA by JULIA MORRIS A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham For the degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Hispanic Studies School of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham December 2009 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis examines subtitles written for heritage films from France and Spain, using six films as case studies. Beginning by offering an overview of the history of subtitling, bringing together a range of different accounts of the field, it aims to situate current approaches to subtitling in relation to changing models of translation and language transfer as well as to developments in the study of audiovisual culture. The increasing importance of subtitling in recent decades, together with rapid technological changes, have had a great impact on subtitling practice, making it necessary to address the technical constraints and solutions diachronically and synchronically, in order to develop a framework for the comparative analysis of film subtitles from different periods and countries. By focusing on films of a particular genre, this limited the extent to which any technical differences might be attributed to internal features, and the choice of the heritage genre allowed greater scrutiny of linguistic and cultural issues in audiovisual translation. -

Please Do What Is Right for the Racehorse

WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 2, 2020 OP/ED: PLEASE DO WHAT 21-DAY VET'S LIST STINT RECOMMENDED FOR CLENBUTEROL IN KY IS RIGHT FOR THE by T. D. Thornton The Kentucky Equine Drug Research Council (EDRC), which RACEHORSE serves as an advisory board to the Kentucky Horse Racing Commission (KHRC), advanced a Dec. 1 recommendation to that full board that would require any horse who receives clenbuterol to be restricted via the veterinarian's list for 21 days and then test clear of that substance prior to being removed from the list and allowed to compete. Kentucky's current clenbuterol regulation requires a prescription that must be filed with the KHRC within 24 hours of dispensing the drug and a withdrawal time of 14 days, according to Bruce Howard, DVM, who serves as the equine medical director for the KHRC. Cont. p5 IN TDN EUROPE TODAY BEACH SEASON AT TATTERSALLS ON TUESDAY Asmussen argues that closing tracks one day a week is not in the Beach Frolic (GB) (Nayef) brought 2.2 million guineas from MV best interests of the horse or horse safety | Sarah Andrew Magnier during Tuesday’s session of the Tattersalls December Mare Sale. Chris McGrath and Emma Berry report from Park by Steve Asmussen Paddocks. Click or tap here to go straight to TDN Europe. With heightened accountability for the health and welfare of horses, trainers today are being held to the highest of standards--as we should. However, we can see every day that racetracks and track ownership groups are not held to that same standard. -

Steve Ashley

1 60's and 70's: Folk, Folk Rock ALBION (COUNTRY) BAND (ENG) UK US Battle of the Field 15 1976 Island HELP 25 Antilles 310 7 1985 Carthage CGLP 4420 (RI) The Prospect Before Us 15 1976 Harvest SHSP 4059 Rise up like the Sun 10 1978 Harvest SHSP 4092 7 1985 Carthage CGLP 4431 (RI) Lark Rise to Candleford 10 1979 Charisma CDS 4020 Light Shining 10 1982 Albino ALB 001 -- Shuffle Off 10 1983 Spindrift SPIN 103 -- Under the Rose 10 1984 Spindrift SPIN 110 -- A Christmas Present 15 1985 Fun FUN 003 -- Stella Maris 10 1987 Spindrift SPIN 130 -- The Wild Side of Town 10 1988 Celtic Music CM 042 -- I got new Shoes 10 1988 Spindrift SPIN 132 -- Give me a Saddle, I'll trade You a Car 7 1989 Topic 12 TS 454 -- 1990 7 1990 Topic 12 TS 457 -- Songs from the Shows, Vol. 1 1990 Albino ALB 003 -- Songs from the Shows, Vol. 2 1990 Albino ALB 005 -- BBC Live in Concert 1993 Windsong WINCD 041 -- Acousticity 1993 HTD HTDCD13 -- Captured 1994 HTD HTDCD19 -- The Etchingham Steam Band 1995 Fledg'ling FLED 3002 -- Albion Heart 1995 HTD HTDCD30 -- Demi paradise 1996 HTD HTDCD54 -- The Acoustic Years 1993-97 (Compilation) 1997 HTD HTDCD74 -- Happy Accident 1998 HTD HTDCD82 -- Along the Pilgrim's Way 1998 Mooncrest 028 -- Live At The Cambridge Folk Festival 1998 Strange Fruit CAFECD002 -- The BBC Sessions 1998 Strange Fruit SFRSCD050 -- Before Us Stands Yesterday 1999 HTD HTDCD90 -- Road Movies 2000 Topic TSCD523 -- An Evening With The Albion Band 2002 Talking Elephant TECD016 -- Acousticity on Tour 2004 Talking Elephant TECD061 -- Albion Heart On Tour (Live -

Artist / Bandnavn Album Tittel Utg.År Label/ Katal.Nr

ARTIST / BANDNAVN ALBUM TITTEL UTG.ÅR LABEL/ KATAL.NR. LAND LP KOMMENTAR A 80-talls synthpop/new wave. Fikk flere hitsingler fra denne skiva, bl.a The look of ABC THE LEXICON OF LOVE 1983 VERTIGO 6359 099 GER LP love, Tears are not enough, All of my heart. Mick fra den første utgaven av Jethro Tull og Blodwyn Pig med sitt soloalbum fra ABRAHAMS, MICK MICK ABRAHAMS 1971 A&M RECORDS SP 4312 USA LP 1971. Drivende god blues / prog rock. Min første og eneste skive med det tyske heavy metal bandet. Et absolutt godt ACCEPT RESTLESS AND WILD 1982 BRAIN 0060.513 GER LP album, med Udo Dirkschneider på hylende vokal. Fikk opplevd Udo og sitt band live på Byscenen i Trondheim november 2017. Meget overraskende og positiv opplevelse, med knallsterke gitarister, og sønnen til Udo på trommer. AC/DC HIGH VOLTAGE 1975 ATL 50257 GER LP Debuten til hardrocker'ne fra Down Under. AC/DC POWERAGE 1978 ATL 50483 GER LP 6.albumet i rekken av mange utgivelser. ACKLES, DAVID AMERICAN GOTHIC 1972 EKS-75032 USA LP Strålende låtskriver, albumet produsert av Bernie Taupin, kompisen til Elton John. HEADLINES AND DEADLINES – THE HITS WARNER BROS. A-HA 1991 EUR LP OF A-HA RECORDS 7599-26773-1 Samlealbum fra de norske gutta, med låter fra perioden 1985-1991 AKKERMAN, JAN PROFILE 1972 HARVEST SHSP 4026 UK LP Soloalbum fra den glimrende gitaristen fra nederlandske progbandet Focus. Akkermann med klassisk gitar, lutt og et stor orkester til hjelp. I tillegg rockere som AKKERMAN, JAN TABERNAKEL 1973 ATCO SD 7032 USA LP Tim Bogert bass og Carmine Appice trommer.