CAFOD Workshops on Laudato Si’ CONTRIBUTION to a GLOBAL DIALOGUE on PROGRESS ______Augusto Zampini Davies, for CAFOD

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

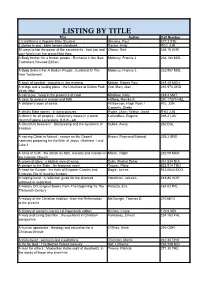

Parish Library Listing

LISTING BY TITLE Title Author Call Number 2 Corinthians (Lifeguide Bible Studies) Stevens, Paul 227.3 STE 3 stories in one : bible heroes storybook Rector, Andy REC JUN 50 ways to tap the power of the sacraments : how you and Ghezzi, Bert 234.16 GHE your family can live grace-filled lives A Body broken for a broken people : Eucharist in the New Moloney, Francis J. 234.163 MOL Testament Revised Edition A Body Broken For A Broken People : Eucharist In The Moloney, Francis J. 232.957 MOL New Testament A book of comfort : thoughts in late evening Mohan, Robert Paul 248.48 MOH A bridge and a resting place : the Ursulines at Dutton Park Ord, Mary Joan 255.974 ORD 1919-1980 A call to joy : living in the presence of God Matthew, Kelly 248.4 MAT A case for peace in reason and faith Hellwig, Monika K. 291.17873 HEL A children's book of saints Williamson, Hugh Ross / WIL JUN Connelly, Sheila A child's Bible stories : in living pictures Ryder, Lilian / Walsh, David RYD JUN A church for all peoples : missionary issues in a world LaVerdiere, Eugene 266.2 LAV church Eugene LaVerdiere, S.S.S - edi A Church to believe in : Discipleship and the dynamics of Dulles, Avery 262 DUL freedom A coming Christ in Advent : essays on the Gospel Brown, Raymond Edward 226.2 BRO narritives preparing for the Birth of Jesus : Matthew 1 and Luke 1 A crisis of truth - the attack on faith, morality and mission in Martin, Ralph 282.09 MAR the Catholic Church A crown of glory : a biblical view of aging Dulin, Rachel Zohar 261.834 DUL A danger to the State : An historical novel Trower, Philip 823.914 TRO A heart for Europe : the lives of Emporer Charles and Bogle, James 943.6044 BOG Empress Zita of Austria-Hungary A helping hand : A reflection guide for the divorced, Horstman, James L. -

Solidarity As Spiritual Exercise: a Contribution to the Development of Solidarity in the Catholic Social Tradition

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by eScholarship@BC Solidarity as spiritual exercise: a contribution to the development of solidarity in the Catholic social tradition Author: Mark W. Potter Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/738 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2009 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Boston College The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Department of Theology SOLIDARITY AS SPIRITUAL EXERCISE: A CONTRIBUTION TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF SOLIDARITY IN THE CATHOLIC SOCIAL TRADITION a dissertation by MARK WILLIAM POTTER submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2009 © copyright by MARK WILLIAM POTTER 2009 Solidarity as Spiritual Exercise: A Contribution to the Development of Solidarity in the Catholic Social Tradition By Mark William Potter Director: David Hollenbach, S.J. ABSTRACT The encyclicals and speeches of Pope John Paul II placed solidarity at the very center of the Catholic social tradition and contemporary Christian ethics. This disserta- tion analyzes the historical development of solidarity in the Church’s encyclical tradition, and then offers an examination and comparison of the unique contributions of John Paul II and the Jesuit theologian Jon Sobrino to contemporary understandings of solidarity. Ultimately, I argue that understanding solidarity as spiritual exercise integrates the wis- dom of John Paul II’s conception of solidarity as the virtue for an interdependent world with Sobrino’s insights on the ethical implications of Christian spirituality, orthopraxis, and a commitment to communal liberation. -

Initial Proclamation of Christ in Melanesia: a Situationer

Study Days on the Salesian Mission and the Initial Proclamation of Christ in Oceania Acts of the Study Days on the Salesian Mission and the Initial Proclamation of Christ in Oceania in the Context of Traditional Religions and Cultures, and Cultures in the Process of Secularisation August 21 – 25, 2011 Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea edited by Alfred Maravilla SDB Missions Department & FMA Sector for Mission ad/inter Gentes Rome 2013 Editrice S.D.B. Edizione extra commerciale Direzione Generale Opere Don Bosco Via della Pisana, 1111 Casella Postale 18333 00163 Roma Table of Contents INTRODUCTION Don Bosco come to Oceania!.. X The Study Days ........ X Rediscover the Dynamics of Initial Proclamation .... X Fr. Václav Klement SDB, General Councillor for the Missions What Do We “Say” about Jesus to the Peoples of Oceania?..... X Sr. Alaíde Deretti FMA, General Councillor for Mission ad/inter Gentes An Overview of the Topic of Study Days from Prague to Port Moresby ..... X Fr. Alfred Maravilla SDB PART I. ANALYSIS OF THE SITUATION Initial Proclamation of Christ in Melanesia: A Situationer.. X Fr. John Cabrido SDB Towards a Common Understanding of Initial Proclamation in Oceania according to Church Documents and in Ecclesia in Oceania .... X Sr. Pamela Vecina FMA PART II. STUDY & REFLECTION Initial Proclamation of Christ in the Context of Traditional Cultures and Religions in Melanesia.... X Fr. Franco Zocca SVD A Response to Franco Zocca.... X Fr. Peter Baquero SDB Initial Proclamation in Societies in the Process of Secularisation.. X Fr. David Willis OP A Response to David Willis ...... X Sr. Margaret Bentley FMA PART III. -

Catholic Social Teaching and the Ethics of Public Policy Outcomes in New Zealand

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. ARE WE DOING GOOD? Catholic Social Teaching and the ethics of public policy outcomes in New Zealand A THESIS SUBMITTED IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN PUBLIC POLICY MASSEY UNIVERSITY ALBANY BRENDA MARGARET RADFORD 2010 i Dedicated to my father John Robert Fittes 1920 – 2005 His calm guidance shaped my ethical perspective and sense of fair play in the light of our rich spiritual heritage Requiescat in pace ii ABSTRACT From the perspective that avoidable social and environmental injustices exist in New Zealand, this research examines the ethics of public policy. It suggests that our society would be more justly sustainable if the ethics of policy outcomes were to supersede political expediency as the dominant influence in government’s decision-making. An Appreciative Inquiry with expert interviewees is applied to the two-part proposition that: (a) a greater focus on ethics and social morality is required for effective policy-making; and (b) the application of the principles of Catholic Social Teaching would enhance the ethical coherence of government policy, programme and service development. The research has found that the public policy system in New Zealand enables its workers to ‘do well,’ but often prevents them from ‘doing good,’ in policy domains such as housing and employment. Erroneous assumptions by policy actors that their work is morally neutral limit their appreciation of the effects that government decisions have on society and the natural environment. -

New Evangelization, Conversion and Catholic Education

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2013 New evangelization, conversion and Catholic education Mark Tynan University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Religion Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Tynan, M. (2013). New evangelization, conversion and Catholic education (Master of Philosophy (MPhil)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/97 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 University of Notre Dame Sydney New Evangelization, Conversion and Catholic Education Mark Tynan Bachelor of Arts Honours (Psychology) Graduate Diploma of Education (Secondary) 20103447 A dissertation submitted in fulfillment of the Masters of Philosophy (Theology) 23rd of August 2013. 2 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Chapter 1. Identifying the need for the New Evangelization ......................................................... -

“You Will Receive Power When the Holy Spirit Has Come Upon You; and You Will Be My Witnesses ” (Acts 1:8)

XXIII WORLD YOUTH DAY MESSAGE OF THE HOLY FATHER BENEDICT XVI TO THE YOUNG PEOPLE OF THE WORLD ON THE OCCASION OF THE XXIII WORLD YOUTH DAY, 2008 “You will receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you; and you will be my witnesses ” (Acts 1:8) My dear young friends! 1. The XXIII World Youth Day I always remember with great joy the various occasions we spent together in Cologne in August 2005. At the end of that unforgettable manifestation of faith and enthusiasm that remains engraved on my spirit and on my heart, I made an appointment with you for the next gathering that will be held in Sydney in 2008. This will be the XXIII World Youth Day and the theme will be: “You will receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you; and you will be my witnesses” (Acts 1:8). The underlying theme of the spiritual preparation for our meeting in Sydney is the Holy Spirit and mission. In 2006 we focussed our attention on the Holy Spirit as the Spirit of Truth. Now in 2007 we are seeking a deeper understanding of the Spirit of Love. We will continue our journey towards World Youth Day 2008 by reflecting on the Spirit of Fortitude and Witness that gives us the courage to live according to the Gospel and to proclaim it boldly. Therefore it is very important that each one of you young people - in your communities, and together with those responsible for your education - should be able to reflect on this Principal Agent of salvation history, namely the Holy Spirit or the Spirit of Jesus. -

Acta Apostolicae Sedis

An. et vol. XCIX 3 Martii 2007 N. 3 ACTA APOSTOLICAE SEDIS COMMENTARIUM OFFICIALE Directio: Palazzo Apostolico – Citta` delVaticano – Administratio: Libreria Editrice Vaticana ACTA BENEDICTI PP. XVI ADHORTATIO APOSTOLICA POSTSYNODALIS Ad Episcopos Sacerdotes Consecratos Consecratasque necnon Christifideles laicos de Eucharistia vitae missionisque Ecclesiae fonte et culmine EXORDIUM 1. Sacramentum caritatis,1 Sanctissima Eucharistia donum est Iesu Christi se ipsum tradentis, qui Dei infinitum nobis patefacit in singulos ho- mines amorem. Hoc in mirabili Sacramento « maior » manifestatur amor is, qui efficit « ut animam suam quis ponat pro amicis suis » (Io 15, 13). Iesus enim « in finem dilexit eos » (Io 13, 1). Verbis his infinitae actum humilitatis exhibet Evangelista quem Ille patravit: antequam in cruce pro nobis moria- tur, praecingens se linteo, suorum discipulorum pedes lavat. Eodem quidem modo in eucharistico Sacramento Iesus « in finem », usque scilicet ad corpus sanguinemque tradendum, diligere nos pergit. Qui stupor pro illis factis Do- minique verbis Apostolorum inter cenandum invasit corda! Quam admiratio- nem in cordibus nostris concitare debet eucharisticum Mysterium! Veritatis alimonia 2. In altaris Sacramento, Dominus obviam se dat homini, ad imaginem ac similitudinem Dei creato (cfr Gn 1, 27), itineris comitem se praebens. Hoc enim sacramento cibus fit Dominus hominis, veritatem libertatemque appe- tentis. Una quandoquidem veritas nos liberos revera reddit (cfr Io 8, 36), 1 Cfr S. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, III, q. 73, art. 3. 106 Acta Apostolicae Sedis — Commentarium Officiale Christus fit pro nobis Veritatis cibus. Cum hominis naturam plane perspiceret sanctus Augustinus, collustravit quemadmodum sua sponte, non vi, movere- tur homo, cum coram illa re esset, eum alliciente ac desiderium in eo conci- tante. -

Dissertation

DISSERTATION Inculturation: Rooting the Gospel firmly in Ghanaian Culture. A Necessary Requirement for Effective Evangelization for the Catholic Church in Ghana. Verfasser Mag. Emmanuel Richard Mawusi angestrebter akademischer Grad Zur Erlangung des akademischen Doktorgrades der Theologie (Dr. Theo.) Wien, im Mail, 2009 Studenkennzahl: 0006781 Dissertationsgebiet Dogmatik Betreuer: Univ. Prof. Dr. Bertram Stubenrauch ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to express my sincere thanks, gratitude and appreciation to all whose collaboration and support enabled me to complete this work. During the period of my studies and the subsequent writing of this Thesis, I was privileged to benefit from the magnanimity and benevolence of various individuals whose invaluable assistance has enabled me to complete this work. I wish to express my special thanks to Univ.Prof. Dr. Bertram Stubenrauch, of the Lehrstuhl für Dogmatik und Ökumenische Theologie, Katholisch-Theologische Fakultät, Ludwig-Maximillians-Universität, München, Deutschland, who directed my doctoral Thesis. I am most grateful to him for his supervision, guidance and especially for reading through the entire work and making the necessary corrections and suggestions. I am also grateful to Univ. Prof. Mag. Dr. Ingeborg Gerda Gabriel, Vorständin des Instituts für Sozialethik, Universität Wien, for her assessment of the entire work.. I am equally indebted to my Mag. William Bush of the Department of Social Ethic, University of Vienna for reading through the entire work and making the necessary corrections. I am grateful to Univ. Prof. Dr. Paul Zulehner, of the Pastoral Theological Faculty, University of Vienna. To all who helped in one way or the other, many thanks and gratitude. I owe special gratitude to the Archdiocese of Vienna, Stift Klosterneuburg and Afro- Asiatische Institut - Vienna (AAR ARGE) for supporting me financially during the period of my Studies at the University of Vienna. -

Doniosłość Wschodniej Kodyfikacji Jana Pawła Ii W Aspekcie Kan

STUDIA PRAWNO-EKONOMICZNE, t. LXXXIII, 2011 PL ISSN 0081-6841 s. 63–101 Ewa GAJDA* DONIOSŁOŚĆ WSCHODNIEJ KODYFIKACJI JANA PAWŁA II W ASPEKCIE KAN. 1 CIC I KAN. 1 CCEO 1. Zagadnienia wstępne Karol Kardynał Wojtyła, wybrany na konklawe 16 października 1978 r. papieżem, przybrał imię Jana Pawła II. Pontyfikat Jana Pawła II był jednym z najdłuższych w historii Kościoła katolickiego. Nie wymaga przypomnienia, że Jan Paweł II wprowadził Kościół w trzecie tysiąclecie (List Apostolski Tertio millenio adveniente z 10 listopada 1994 r.)1, a nauczanie papieskie jest niezwykle bogate. Magisterium papieża Jana Pawła II zawiera – co oczywiste – doktrynę katolicką, teologię moralną, teologię duchową. Główne dokumen- ty pontyfikatu Jana Pawła II to: 14 encyklik, 15 adhortacji apostolskich2, * Dr, Katedra Prawa Kanonicznego, Uniwersytet Mikołaja Kopernika w Toruniu. 1 Zob. np. La documentation catholique [dalej jako: DC], 1994, no 2105, s. 1017–1032. 2 Tj. Catechesi tradendae z 16.10.1979 r., DC 1979, no 1773, s. 901–922; Familiaris consortio z 22.11.1981 r., Acta Apostolicae Sedis [dalej jako: AAS] 1981, no 73, s. 81–1991; DC 1982, no 1821, s. 1–37; Redemptoris donum z 25.03.1984 r., AAS 1984, no 76, s. 513–546; DC 1984, no 1872, s. 401–412; Reconciliatio et paenitentia z 2.12.1984 r., AAS 1985, no 77, s. 185–275; DC 1985, no 1887, s. 1–31; Christifidelis laici z 30.12.1988 r., AAS 1989, no 81, s. 393–521; DC 1989, no 1978, s. 152–196; Redemptoris custos z 15.08.1989 r., AAS 1990, no 82, s. 5–34; DC 1989, no 1994, s. -

Principles of the New Evangelization: Analysis and Directions

PRINCIPLES OF THE NEW EVANGELIZATION: ANALYSIS AND DIRECTIONS By Richard M. Rymarz, B.Sc (Hons), M.Sc, M.Ed.Studies, Grad Dip Ed, Ed.D, M.A (Theol). A thesis submitted as full requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Australian Catholic University. School of Theology Faculty of Philosophy and Theology Australian Catholic University Date of Submission: 25th of May 2010 University Research Services Office Melbourne Campus Locked Bag 4115 Fitzroy VIC 3065 1 STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP AND SOURCES This thesis contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a thesis by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree or diploma. No part of this thesis has been submitted towards the award of any other degree or diploma in any other tertiary institution. No other person’s work has been used without due acknowledgement in the main text of the thesis. Richard M. Rymarz 2 ABSTRACT This thesis, after appropriate analysis, proposes a number of principles, which guide both an understanding of the new evangelization as formulated by Pope John Paul II and how the new evangelization can be applied. The key insight of the new evangelization is that growing numbers of people, especially in Western countries such as Australia, whilst retaining what can be termed a “loose” form of Christian affiliation, can no longer be described as having a living sense of the Gospel. This makes these people distinct from the classical focus of missionary activity, namely, those who have never heard the Gospel proclaimed. Pope John Paul II’s exposition of the new evangelization arose from his understanding of key conciliar and post-conciliar documents. -

Pearls in the Deep: Inculturation and Ecclesia in Oceania ”

Bulletin Vol. 36, No. 1/2 - January/February 2004 Rethinking Mission Hugh MacMahon, SSC 3 Towards a Paradigm Shift in Mission Amongst the Indigenous Peoples in Asia Jojo M. Fung, SJ 6 Lʼémigration des Philippins : Chance ou handicap pour le pays ? Michel de Gigord, MEP 18 Les étrangers au Japon frappent à la porte (et au cœur) de lʼÉglise catholique Adolfo Nicolas, SJ 28 Pearls in the Deep: Inculturation and “Ecclesia in Oceania” Philip Gibbs, SVD 32 Sedos Annual Report 2003 Pierre-Paul Walraet, OSC 41 Subject Index 2003 45 Coming Events 48 Sedos - Via dei Verbiti, 1 - 00154 ROMA - TEL.: (+39)065741350 / FAX: (+39)065755787 SEDOS e-mail address: [email protected] - SEDOS Homepage: http://www.sedos.org Servizio di Documentazione e Studi - Documentation and Research Centre Centre de Documentation et de Recherche - Servicio de Documentación e Investigación 2004/2 Editorial SEDOS begins volume 36 of the Bulletin with a prayer for Peace in the World and blessings for all our readers and members. We begin the New Year with the hope for a better understanding and cooperation between all the peoples in the World and a commitment to continue to proclaim the “Good News” as Jesus taught us to. A word of warm greetings to all of you from all the members of the staff and especially from myself as I begin my new service as the person in charge of this office. Counting on your unreserved cooperation SEDOS Bulletin will continue to be published every two months with 48 pages, an increase of 14 pages, so as not to change the over-all annual content. -

Priestly Formation According to Pastores Dabo Vobis* 1

305 ❚Special Issues❚ □ Priestly Formation in the Asian Contexts Priestly Formation According to Pastores Dabo Vobis* 1 Fr. Thomas Cheruparambil 〔St. Joseph Pontifical Seminary, India〕 Introduction 1. Historical Antecedents of Pastores Dabo Vobis 2. The 1990 Synod of Bishops: Some Particulars 3. Highlights on the Priestly Formation in Pastores Dabo Vobis 4. Biblical Foundation of Priesthood 5. Priestly Vocation and the Challenges of Priestly Formation 6. Human Formation 7. Spiritual Formation 8. Intellectual Formation 9. Pastoral Formation 10. Agents of Priestly Formation 11. Ongoing Formation of Priests Conclusion Introduction Jesus the high priest began his public ministry with the following proclamation: “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me because he has anointed *1이 글은 2015년 ‘재단법인 신학과사상’의 연구비 지원을 받아 연구·작성된 논문임. 306 Priestly Formation in the Asian Contexts me to bring good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor” (Lk 4:18, 19). Jesus was filled with the Holy Spirit before his public ministry. All Christian faithful, irrespective of their sate of vocation are called to attain perfection and sanctity. As there are different kinds of vocations, the way to Christian perfection also differs. Every vocation and ministry is specific in its nature. Accordingly, one may speak about the specificity of priestly ministry and formation. In this connection, one may ask: what is the specific nature of priestly formation keeping in mind the specific nature of priestly ministry? There may be different views and opinions about priestly formation.