Historical-Climatology-Of-The-Southern Yukon.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yukon Nuggets by Year Lake Laberge Yukon Nuggets by and There on the Marge of Lake Laberge, I Cremated Alphabet Sam Macgee

HOUGEN BUSINESS YUKON HISTORY HOUGEN FAMILY CONTACT SubmitY QueryUKON N UGGETS before 1890 | 1890s | 1900s | YUKON HISTORY 1910s | 1920s | 1930s | 1940s | 1950s | 1960s | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s Historical Facts by Year Historical Facts by 1840 1849 1865 1867 1869 1871 1875 1879 1882 1883 1884 1886 1887 Alphabet Yukon Nuggets by Year Lake Laberge Yukon Nuggets by And there on the marge of Lake Laberge, I cremated Alphabet Sam MacGee. That lake, made famous around the Yukon Facts world by Robert Service was named for a Quebecer. Hamacher Photos Like many other place names in the Yukon, Lake Laberge had at least several native names. In 1862, explorer Aurel Krause recorded the Tlinget name as Print-Friendly Version Tahini-wud. In 1883, the American explorer Frederick Schwatka , recorded the Tagish name "Kluk-tas-si". But it was William Dall , director of the Scientific corp of the Western Union Telegraph expedition, who gave the lake its present day name. He named Lake Laberge after Michael Laberge of Chateauguay, Quebec. Laberge along with Frank Ketchum of New Brunswick, were explorers for the Western Union who came up river from Fort Yukon to Fort Selkirk in 1867. They were looking for a possible route for the Collins Overland Telegraph line being built from New York to Paris. No-one knows for sure if Michael Laberge ever saw his lake, but it is clear that he had it described to him by native people who lived along the river. The Collins Telegraph line was never built, but the lake went on to Charles Labarge, a relative, served on the Northwestel Board. -

Chilkoot Trail and Yukon River Canoe

The Historic Klondike Route Hike the Chilkoot Trail and Canoe the Yukon River on an 18 day trip following in the footsteps of Yukon Gold Rush Stampeders! “The Klondike Gold Rush captured the imagination of the world. Rich and poor, young and old, women and men were attracted to the Klondike from all parts of the globe. No imagine better represents this historic event than the endless line of stampeders struggling over the Chilkoot Pass during the winter of 1897-98. Today the Chilkoot Trail National and Klondike Gold Rush National Historic Park commemorate this extraordinary journey. The contract between the scenic grandeur of the coastal mountains and the fragile remains of the stampeders’ goods and temporary structures make the Chilkoot a unique backcountry trail.” A hiker’s guide to the Chilkoot trail Historic Klondike Route Information Join us for 18 days of adventure in the Alaska and the Yukon. We’ll start our trip in historic Skagway, Alaska with a 5-day hike over the Chilkoot Trail, traveling in the footsteps of gold rushers from 100 years ago. Once over the trail we’ll trade hiking boots for paddles and begin the 400 miles of canoeing that will bring us to Dawson City Yukon, and the heart of the Klondike gold country. Along the way we’ll pass derelict steam ships, native villages, gold dredges, current day fish camps, trappers cabins, Fort Selkirk, and other relics from the Gold Rush. We’ll also visit Whitehorse, the capital of the Yukon, we’ll run the famous Five Finger Rapids, and pass through Lake Labarge. -

Pits 99Front Pages

GranularGranular ResourcesResources DirectoryDirectory YukonYukon Indian Affairs and Northern Development Canada 1999 Granular Resources Directory Yukon Indian Affairs and Northern Development Canada 1999 Prepared by Inukshuk Planning & Development In association with K-L Services, Whitehorse © 1999, Indian Affairs and Northern Development, Canada Recommended citation: Inukshuk Planning and Development, 1999. Granular Resources Directory: Yukon. Prepared for the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, Ottawa, Canada, by Inukshuk Planning and Development, Whitehorse, Yukon, in association with K-L Services, Whitehorse, Yukon. March, 1999. 30 pages. Additional copies of this directory may be obtained from: Land Use Section, Land Resources Northern Affairs Program - Yukon Indian and Northern Affairs Canada Room 320 – 300 Main Street Whitehorse, Yukon Y1A 2B5 For further information on this directory and other northern granular resources studies, contact: Manager, Land Programs Northern Affairs Program Indian and Northern Affairs Canada Room 618, North Tower Les Terrasses de la Chaudiere Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0H4 PREFACE The roles and responsibilities of governments and institutions in the North are evolving rapidly as a result of land claims and self-government agreements, devolution to the territorial governments and the creation of a new territory, Nunavut. New institutions of public government with responsibilities for land use planning and resources management are being created pursuant to land claim settlements. Resource management boards have, or will assume from DIAND, many of its historical regulatory responsibilities. However, in the interim, DIAND is still responsible for managing federal lands in a way that complements the activities of the new institutions and governments. This includes, as a specific component of DIAND’s sustainable development strategy, continuing to develop a program for the effective management of granular resources. -

Yrqhistory.Pdf

About the Yukon River The Yukon River was called Kweek-puk (Great River) by the Alaskan Inupiat, and Kwitchpak by the exploring Russians. In the Yukon Territory it is Takambo (Wide Open Waters Place) to the Kwanlin Dun at Whitehorse and Tage Cho Ge to the Selkirk people at Pelly Crossing/Fort Selkirk. Robert Campbell, a trader for the Hudson’s Bay Company (H.B.Co.), travelled to what he called the “Lewes” River in 1843 via the Liard and Pelly rivers. John Bell, also of the H.B.Co., first saw the “Youcon” River in 1845 when he explored the western Mackenzie drainage and travelled down the Porcupine River. In 1862 Campbell confirmed that his “Lewes” and Bell’s “Youcon” were the same river. At various times the source of the Yukon was thought to be the Teslin, the Lewes or the Pelly rivers. After the Klondike Gold Rush of 1897-98, the riverboat pilots distinguished parts of the river by name, such as the Fiftymile from Marsh Lake to Lake Laberge, and the Thirtymile from Lake Laberge to the Teslin. In 1964 “Yukon River” was applied to the entire watercourse from Marsh Lake in the Yukon Territory to the Bering Sea at the Alaska coast. By whatever name, the Yukon has been a major transportation route and a bountiful source of food since the last Ice Age. – from the Yukon Territorial Government sign at the Yukon River bridge on the Alaska Highway, near where the river begins at Marsh Lake History of the Yukon River Quest ‘The race to the midnight sun’ By JEFF BRADY YRQ Media Director The Yukon River Quest had its beginnings during the Klondike Gold Rush Centennial years. -

Studies on the Freshwater and Anadromous Fishes of the Yukon River Within Canada

I." Environment Canada Environnement Canada Fisheries Service des peches and Marine Service et des sciences de la mer Studies on the freshwater and anadromous fishes of the Yukon River within Canada C.E. Walker PAC T/76-7 North B.C. & Yukon Br Pacific Region STUDIES ON THE FRESHWATER AND ANADROMOUS FISHES OF THE YUKON RIVER WITHIN CANADA By: C.E. Walker PAC T/76-7 Department of the Environment Fisheries and Harine Service 1090 \vest Pender Street Vancouver, B. C. V6E 2P1 July, 1976 i ABSTRACT Characteristics of the adult chinook and chum salmon populations of the Yukon River within Canada are described. Significant differences were found between the composition of the catch and the composition of the escapement in terms of sex and length. It is hypothesized that any change in the fishery from wheels to gillnet will result in greater catch of larger size fish and also of females. Such a change may have severe con sequences on the reproductive capacity of the populations. Ten fish populations, other than adult salmon, are described for an area from Tatchun Creek to Fort Selkirk. Salmon is the most abundant fish, with longnose sucker, Arctic grayling and slimy sculpin occurring in this order. Growth data are presented for some species. In general, the growth of fish in the Yukon River is slower than that in tributary st~eams and other waterways of the territory. The predictive value of pre-determining the location of salmon spawning habitat based on pinpointing areas that are ice-free and/or have ground water intrusion was nil. -

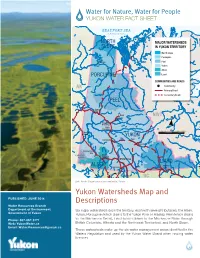

Yukon Watersheds Map and Descriptions

Water for Nature, Water for People YUKON WATER FACT SHEET Left: North Slope tundra and wetlands, Yukon Yukon Watersheds Map and PUBLISHED: JUNE 2014 Descriptions Water Resources Branch Department of Environment Six major watersheds drain the territory, each with several tributaries: the Alsek, Government of Yukon Yukon, Porcupine (which drains to the Yukon River in Alaska), Peel (which drains to the Mackenzie Delta), Liard (which drains to the Mackenzie Basin through Phone: 867-667-3171 Web: YukonWater.ca British Columbia, Alberta and the Northwest Territories), and North Slope. Email: [email protected] These watersheds make up the six water management areas identified in the Waters Regulation and used by the Yukon Water Board when issuing water licences. 1 Water for Nature, Water for People YUKON WATER FACT SHEET City of Whitehorse, and Yukon River Yukon River Basin (including the Alsek River Basin Porcupine River Basin) The Alsek River drains the southwestern portion of the Yukon to the Pacific Ocean. It is classified as a The Yukon River Headwaters contains the Southern Canadian Heritage River because of its significant Lakes region of Yukon and Northern British Columbia; natural resources: massive ice fields, high mountain there are glaciers throughout the mountains of these peaks, unique geologic history, coastal and interior headwaters. The Teslin River joins the Yukon River plant communities, significant grizzly bear population, north of Lake Laberge, contributing water mainly from and diverse bird species. snowmelt runoff in the upper portions of the basin. The Pelly and Stewart Rivers drain the eastern portion of the drainage, including mountainous terrain. -

Yukon River: Thirty Mile Section 20-Year Monitoring Report

Yukon River: Thirty Mile Section 20-year Monitoring Report Prepared for: Yukon Parks Department of Environment Government of Yukon and the Canadian Heritage Rivers Board Prepared by: Bruce K. Downie PRP Parks: Research & Planning Inc. Whitehorse, Yukon Purpose of the Report The Thirty Mile Section of the Yukon River was designated as a Canadian Heritage River in 1991 – the second designation in Yukon. The CHRS requires regular monitoring of the natural, heritage and recreational values underpinning each designation. This report presents the results of the 20- year review of the river values and key elements of the intended and articulated management strategies for the area. This analysis points out the characteristics and qualities of the designated river that have been consistently and naturally maintained as well as those activities and management actions being implemented to ensure continued integrity of the river values. This report is not intended to be a thorough review of the management plan but will make a contribution to formal management plan reviews when they are undertaken. Acknowledgements Thanks are due to those individuals consulted through this analysis and especially to the dedicated individuals in Yukon and First Nations governments who continue to work towards the protection of the natural and cultural values of the Thirty Mile segment of the Yukon River. Thanks are also extended to the Parks Canada Agency for funding this project in part and providing support through the Canadian Heritage Rivers Board Secretariat. -

PUBLIC FLOOD UPDATE July 30, 2021 at 4:00 P.M

PUBLIC FLOOD UPDATE July 30, 2021 at 4:00 p.m. The Emergency Measures Organization and Water Resources Branch are working closely to monitor water levels across the Yukon and provide accurate information to communities. There are evacuation alerts in effect for: areas of Lake Laberge, Tagish, Marsh Lake and Lewes River Road An evacuation order is in effect for: a property on Shallow Bay Road at Lake Laberge For more details about these evacuation alerts or orders, visit Yukon.ca/emergencies The following advisories are in effect: Flood warning for Southern Lakes is being maintained (issued July 27) Flood warning for Lake Laberge is being maintained (issued July 27) High streamflow advisory for Yukon River at Whitehorse is being maintained (issued July 23) Boil water advisory for residents of Southern Lakes, Lake Laberge, Kusawa Lake and Takhini River areas (issued July 7) Boil water advisory for residents of Army Beach and South M’Clintock with private wells or underground water storage tanks (issued July 7) Boil water advisory for residents of Carmacks with private wells (issued June 25) The following areas are closed: Riverside boardwalks in Carmacks Marsh Lake Recreation Site (Army Beach) including the parking lot, pedestrian bridge and tenting sites Conrad Historic Site Parts of the Marsh Lake campground, including sites 10 to 15 Tagish Campground Extended hours at Waste Management Facilities: Waste Management Facilities are now open 7 days per week in the Southern Lakes and Lake Laberge. The operating hours for specific facilities are: Marsh Lake: Mon-Tue from 6:30 am to 2:30 pm; Wed-Sun from 10:00 a.m. -

Manufacturing a National Identity Using Robert Service's Poetry

k.barnes 2017 The Canadian “North”: Manufacturing a National Identity Using Robert Service’s Poetry Despite having a combined population smaller than the province of Prince Edward Island or the city of Kelowna, the Canadian Territories of Nunavut, Yukon, and the Northwest have a leading role in portraying Canada as a “northern nation”. We are the “True North, strong and free”. Polar bears inhabit our two-dollar coins. Even the inukshuk, a traditional Inuit landmark, is a common sight in modern Canadian iconography, as seen in the 2010 Vancouver Winter Olympics, despite the fact that British Columbia has plenty of local Indigenous symbols and art that could have been appropriated for the same use. As a result, these conceptualizations of the “North1” are both culturally significant and a political focal point for Canada which influences the image of Canadians both domestically and abroad. These images of the North, its landscape and its people play an indelible part in the formation of the Canadian identity. Nevertheless, even though the northern landscape is a major part of Canadian myth- making and identity, very few Canadians have crossed the 60th Parallel to visit this region and even less people live there; for example, less than 35,000 people live in Yukon. Yet it is undeniable that this territory in particular is integral to Canadian lore as a northern, frontier nation, with its imagery of the treacherous Chilkoot Pass, the historic “sin city” of Dawson, the Midnight Sun, and the Northern Lights. With this consideration in mind, some questions arise— why are Canadians so obsessed with the North as a part of our collective identity and where did it come from? There’s a land where the mountains are nameless, And the rivers all run God knows where; 1 I will be capitalizing the word “North”, as I will treat the North if it is a defined place, or character. -

Yukon River Heritage an Illustrated Introduction for River Travellers

Yukon River Heritage An illustrated introduction for river travellers Revised edition © 2013 Government of Yukon, Department of Tourism and Culture ISBN 978-1-55362-654-1 Front cover, top: Men and dog in a boat, ca. 1900. University of Washington Libraries #11633 Front cover, bottom: Mountie Arthur Thornthwaite on Tantalus Butte/Gum Tthi, ca. 1920. YA, Claude and Mary Tidd fonds, #7714 Back cover, top: Chief Isaac (left) and two other Hän men, ca. 1900. YA, AHL collection, #4232 Back cover, background: Gold rush boats on their way to Dawson at the mouth of the Stewart River, 1898. YA, Greenbank collection, 89/19 #14 Back cover, bottom: The Dawson waterfront, 1917. YA, Emil Forrest fonds, 80/60 #590 Please go to www.travelyukon.com for information about planning river trips. Drift Into History An introduction to the heritage of the Yukon River This publication offers a glimpse of some of the heritage sites along the Yukon River. It is intended to give you an idea of the timeless heritage and beauty of one of the world’s great rivers. The booklet is not a comprehensive history The wheelhouse of theS.S. Bailey. and should not be used for YA, H.C. Barley fonds, #5202 navigation purposes. There are books, maps, charts and guides that provide detailed histories or planning and route information. Enjoy your journey. The Yukon River The Yukon River is the fifth longest river in North YA, Eric Hegg fonds, #2783 America. It drains almost 900,000 square kilometres (km), about half of which are in Canada and half in the United States. -

PUBLIC FLOOD UPDATE July 16, 2021 at 1:00 P.M

PUBLIC FLOOD UPDATE July 16, 2021 at 1:00 p.m. The Emergency Measures Organization and Water Resources Branch are working closely to monitor water levels across the Yukon and provide accurate information to communities. There are evacuation alerts in effect for: areas of Lake Laberge, Tagish, Marsh Lake and the Lewes River Road An evacuation order is in effect for: a property on Shallow Bay Road at Lake Laberge For more details about these evacuation alerts or orders, visit Yukon.ca/emergencies The following advisories are in effect: Flood warning for Southern Lakes (issued July 13) Flood warning for Lake Laberge (issued July 13) Flood watch for Kusawa Lake and Takhini River (issued July 9) High streamflow advisory for Yukon River at Carmacks (issued July 9) High streamflow advisory for Yukon River at Whitehorse (issued July 5) Boil water advisory for residents of Southern Lakes, Lake Laberge, Kusawa Lake and Takhini River areas (issued July 7) Boil water advisory for residents of Army Beach and South M’Clintock with private wells or underground water storage tanks (issued July 7) Boil water advisory for residents of Carmacks with private wells (issued June 25) The following areas are closed: Riverside boardwalks and River Drive in Carmacks Marsh Lake Recreation Site (Army Beach) including the parking lot, pedestrian bridge and tenting sites Conrad Historic Site Parts of the Marsh Lake campground, including sites 10 to 15 Tagish Campground Jackfish Bay Road is open to local traffic only Extended hours at Waste Management Facilities: Waste Management Facilities are now open 7 days per week in the Southern Lakes and Lake Laberge. -

Southern Lakes Flood Public Update July 20, 2021 at 6:00 P.M

Southern Lakes Flood public update July 20, 2021 at 6:00 p.m. General update The Government of Yukon has declared a local State of Emergency under the Civil Emergency Measures Act in response to flooding in Southern Lakes and Lake Laberge. An evacuation order was issued for a property on Shallow Bay Road at Lake Laberge. An evacuation alert remains in effect for specific areas of Lake Laberge, Tagish, What is an evacuation alert? and Marsh Lake. Visit This means you need to be ready to leave Yukon.ca/emergencies for more details. on short notice. Flood information sheets are now What is an evacuation order? posted on bulletin boards at all This means you are at risk and must leave sandbag stations, including a sign-up the area immediately and register with the sheet for residents who require Canadian Red Cross by phone or at the volunteer assistance. reception centre. Yukon Emergency Social Both the Hootalinqua sandbag station and Carcross sandbag station have Services and the Red Cross are on standby more than enough filled sandbags. So, to provide supports to evacuees in the we are moving filled sandbags from event of an order. these station to more critical areas in need. There will be plenty of sandbags leftover for property owners to use. The Southern Lakes flood information map can be found on Yukon.ca/emergencies. Water levels as of 11:00 a.m. on July 20 Difference from Rate of increase in Water body Current level (m) 2007 (cm) last 24 hours (cm) Bennett Lake 3.573 8.9 -1.6 Tagish Lake 8.442 4.6 -0.3 Marsh Lake 4.116 13.3 -1.8 Lake Laberge 9.690 39 -1.6 FOR MORE INFORMATION, PLEASE CONTACT: [email protected] or 867-332-7084 Southern Lakes Flood public update July 20, 2021 at 6:00 p.m.