Social Revolution in Circassia: the Interdependence of Religion and the World- System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selected Works of Chokan Valikhanov Selected Works of Chokan Valikhanov

SELECTED WORKS OF CHOKAN VALIKHANOV CHOKAN OF WORKS SELECTED SELECTED WORKS OF CHOKAN VALIKHANOV Pioneering Ethnographer and Historian of the Great Steppe When Chokan Valikhanov died of tuberculosis in 1865, aged only 29, the Russian academician Nikolai Veselovsky described his short life as ‘a meteor flashing across the field of oriental studies’. Set against his remarkable output of official reports, articles and research into the history, culture and ethnology of Central Asia, and more important, his Kazakh people, it remains an entirely appropriate accolade. Born in 1835 into a wealthy and powerful Kazakh clan, he was one of the first ‘people of the steppe’ to receive a Russian education and military training. Soon after graduating from Siberian Cadet Corps at Omsk, he was taking part in reconnaissance missions deep into regions of Central Asia that had seldom been visited by outsiders. His famous mission to Kashgar in Chinese Turkestan, which began in June 1858 and lasted for more than a year, saw him in disguise as a Tashkent mer- chant, risking his life to gather vital information not just on current events, but also on the ethnic make-up, geography, flora and fauna of this unknown region. Journeys to Kuldzha, to Issyk-Kol and to other remote and unmapped places quickly established his reputation, even though he al- ways remained inorodets – an outsider to the Russian establishment. Nonetheless, he was elected to membership of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society and spent time in St Petersburg, where he was given a private audience by the Tsar. Wherever he went he made his mark, striking up strong and lasting friendships with the likes of the great Russian explorer and geographer Pyotr Petrovich Semyonov-Tian-Shansky and the writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky. -

Der VERMUTUNGEN

Das BUCH der VERMUTUNGEN. Marco Polo – Eine Legende und deren Weltbeschreibung am Prüfstand aktueller Forschungspositionen. DIPLOMARBEIT zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Magisters der Philosophie an der Geisteswissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz vorgelegt von Markus Robert HAUSMANN am Institut für Geschichte Begutachter: Ass.-Prof. Mag. Dr. phil. Johannes Giessauf Graz, Dezember 2013 Für mich. Für meine geduldige Familie. Für die (Nach-)Welt und deren Bücherregale. „Bei allem immanenten Interesse an Marco Polos Buch mag man doch zweifeln, ob es über Generationen hinweg auf viele Leser solch anhaltende Faszination ausgeübt hätte ohne die schwierigen Fragen, die es stellt. Es ist ein großartiges Werk voller Rätsel, wobei wir im Vertrauen auf das menschliche Wahrheitsstreben glauben, dass es zu jedem Rätsel eine Lösung gibt.“ (HENRY YULE, The Book of Ser Marco Polo) INHALTSVERZEICHNIS i. | MARCO SEI DANK! 5 I. | PROLOG – EINLEITUNG 6 II. | WER WAREN DIE POLOS? 11 III. | ZWEI SAGENHAFTE REISEN 19 IV. | KONTROVERSIELLE AUTORSCHAFT 37 V. | KOMPLEXITÄTEN DER ÜBERLIEFERUNG 44 V. I. | DIE FAMILIEN DER HANDSCHRIFTEN 44 V. II. | DISKUSSION UND FORSCHUNGSTENDENZEN 49 VI. | KOHÄRENZPROBLEME DES „ITINERARS“ 55 VI. I. | EIN GEO-ETHNOGRAPHISCHES DICKICHT 55 VI. II. | CHINESISCHE NAMEN IM PERSISCHEN KLEID 60 VII. | VERGESSENE ZIVILISATIONS-/KULTURASPEKTE 64 VII. I. | SCHRIFTLOSE DRUCKWERKE 67 VII. II. | VERSCHMÄHTE AUFGÜSSE 71 VII. III. | VON EINGEBUNDENEN FÜßEN UND KORMORANEN 73 VII. IV. | DIE ÜBERSEHENE GROßE MAUER 78 VIII. | EINE BEEINDRUCKENDE FÜLLE AN FAKTEN 83 IX. | VERMEINTLICHE ÄMTER UND AUFGABEN 96 IX. I. | DIE SELBSTERNANNTEN BELAGERUNGS-EXPERTEN 96 IX. II. | RÄTSELHAFTE GOUVERNEURSWÜRDEN 99 IX. III. | EIN JUGENDLICHER EMISSÄR & SEINE DIPLOMATEN 105 X. | DAS SCHWEIGEN DER QUELLEN 112 XI. -

ASTRA Salvensis, Supplement No. 1/2021 173 the ROLE OF

ASTRA Salvensis, Supplement no. 1/2021 THE ROLE OF ULUSES AND ZHUZES IN THE FORMATION OF THE ETHNIC TERRITORY OF THE KAZAKH PEOPLE Aidana KOPTILEUOVA1, Bolat KUMEKOV1, Meiramkul T. BIZHANOVA2 1Department of Eurasian Studies, L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University, Nur-Sultan, Republic of Kazakhstan 2Department of History of Kazakhstan, Al-Farabi Kazakh National University, Almaty, Republic of Kazakhstan Abstract: The article is devoted to one of the pressing issues of Kazakh historiography – the problems of the formation of the ethnic territory of the Kazakh people. The ethnic territory of the Kazakh people is the national borders of today’s Republic of Kazakhstan, inherited from the nomadic ancestors – the Kazakh Khanate. Uluses are a distinctive feature of the social structure of nomads, Zhuzes are one of the Kazakh nomads. In this regard, our goal is to determine their role in shaping the ethnic territory of the Kazakh people. To do this, a comparative analysis will be made according to different data and historiographic materials, in addition, the article will cover the issues of the appearance of the zhuzes system in Kazakh society and its stages. As a result of this work, the authorial offers are proposed – the hypothesis of the gradual formation of the ethnic territory and the Kazakh zhuzes system. Keywords: Kazakh historiography, Middle ages, the Mongol period, Kazakh Khanate, gradual formation. The formation of the ethnic territory of the Kazakh people is closely connected not only with the political events of the period under review, but with ethnic processes. Kazakhs consist of many clans and tribes that have their hereditary clan territories. -

Review the Legacy of Nomadic Empires in Steppe Landscapes Of

ISSN 10193316, Herald of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 2009, Vol. 79, No. 5, pp. 473–479. © Pleiades Publishing, Ltd., 2009. Original Russian Text © A.A. Chibilev, S.V. Bogdanov, 2009, published in Vestnik Rossiiskoi Akademii Nauk, 2009, Vol. 79, No. 9, pp. 823–830. Review Information about the impact of nomadic peoples on the landscapes of the steppe zone of northern Eurasia in the 18th–19th centuries is generalized against a wide historical–geographical background, and the objec tives of a new scientific discipline, historical steppe studies, are substantiated. DOI: 10.1134/S1019331609050104 The Legacy of Nomadic Empires in Steppe Landscapes of Northern Eurasia A. A. Chibilev and S. V. Bogdanov* The steppe landscape zone covering more than settlements with groundbased or earthsheltered 8000 km from east to west has played an important role homes were situated close to fishing areas, watering in the history of Russia and, ultimately, the Old World places, and migration paths of wild ungulates. Steppe for many centuries. The ethnogenesis of many peoples bioresources were used extremely selectively. of northern Eurasia is associated with the historical– Nomadic peoples affected the steppe everywhere. The geographical space of the steppes. The continent’s nomadic, as opposed to semisedentary, lifestyle steppe and forest–steppe vistas became the cradle of implies a higher development of the territory. The nomadic cattle breeding in the early Bronze Age (from zone of economic use includes the whole nomadic the 5th through the early 2nd millennium B.C.). By area. Owing to this, nomads had an original classifica the 4th millennium B.C., horses and cattle were pre tion of its parts with regard to their suitability for set dominantly bred in northern Eurasia. -

The Northern Black Sea Region in Classical Antiquity 4

The Northern Black Sea Region by Kerstin Susanne Jobst In historical studies, the Black Sea region is viewed as a separate historical region which has been shaped in particular by vast migration and acculturation processes. Another prominent feature of the region's history is the great diversity of religions and cultures which existed there up to the 20th century. The region is understood as a complex interwoven entity. This article focuses on the northern Black Sea region, which in the present day is primarily inhabited by Slavic people. Most of this region currently belongs to Ukraine, which has been an independent state since 1991. It consists primarily of the former imperial Russian administrative province of Novorossiia (not including Bessarabia, which for a time was administered as part of Novorossiia) and the Crimean Peninsula, including the adjoining areas to the north. The article also discusses how the region, which has been inhabited by Scythians, Sarmatians, Greeks, Romans, Goths, Huns, Khazars, Italians, Tatars, East Slavs and others, fitted into broader geographical and political contexts. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. Space of Myths and Legends 3. The Northern Black Sea Region in Classical Antiquity 4. From the Khazar Empire to the Crimean Khanate and the Ottomans 5. Russian Rule: The Region as Novorossiia 6. World War, Revolutions and Soviet Rule 7. From the Second World War until the End of the Soviet Union 8. Summary and Future Perspective 9. Appendix 1. Sources 2. Literature 3. Notes Indices Citation Introduction -

Appanage Russia

0 BACKGROUND GUIDE: APPANAGE RUSSIA 1 BACKGROUND GUIDE: APPANAGE RUSSIA Hello delegates, My name is Paul, and I’ll be your director for this year. Working with me are your moderator, Tristan; your crisis manager, Davis; and your analysts, Lawrence, Lilian, Philip, and Sofia. We’re going to be working together to make this council as entertaining and educational (yeah yeah, I know) as possible. A bit about me? I am a third year student studying archaeology, and this is also my third year doing UTMUN. Now enough about me. Let’s talk about something far more interesting: Russia. Russian history is as brutal as the land itself, especially during our time of study. Geography sets the stage with freezing winters and mud-ridden summers. This has huge effects on how Russia’s economy and society functions. Coupled with that are less-than-neighbourly neighbours: the power- hungry nations of western and central Europe, The Byzantine Empire (a consistent love- hate partner), and (big surprise) various nomadic groups, one of which would eventually pose quite a problem for the idea of Russian independence. Uh oh, it looks like it’s suddenly 1300 and all of you are Russian Princess.You are all under the rule of Toqta Khan of the Golden Horde (Halperin, 2009), one of the successor states to Genghis Khan’s massive empire. Bummer. But, there is hope: through working together and with wise reactions to the crises that will inevitably come your way, you might just be able shake off the Tatar Yoke. Of course, your problems are not so limited. -

A Brief History of Kabarda

A Brief History of Kabarda [from the Seventh Century AD] Amjad Jaimoukha T he Russians have been writing Kabardian (and Circassian) history according to their colonial prescriptions for more than a century, ever since they occupied Circassia in the middle years of the 19th century. Simplistic and oftentimes ridiculous accounts of this history were produced in the course of this time. Until this day, these historiographies, with added clauses to reduce the level of inanity and circumvent the rampant contradictions, constitute the official historical narrative in the Kabardino-Balkarian Republic (and with slight variations in the other ‘Circassian’ republics, namely the Karachai-Cherkess Republic and the Republic of Adigea). For one, the Kabardians were deemed to have opted to join Russia in the 16th century (much more on this ‘Union’ in the course of this article). In 1957, big celebrations were held in Kabarda commemorating the 400th anniversary of the ‘joyful’ event that saved the Kabardians from perdition. A statue was erected as a symbol of the fictitious union of Kabarda with Russia in downtown Nalchik. The Circassian maiden with an uplifted scroll is exquisite Gwascheney (or Gwaschene; Гуащэней, е Гуащэнэ), daughter of Temryuk Idar (Teimriqwe Yidar; Идар и къуэ Темрыкъуэ), who was betrothed to Ivan IV (1530-1584) on 21 August 1561 AD, to cement the treaty between Temryuk, Prince of Princes of Kabarda, and Ivan the Terrible, ‘Tsar of All Russia’.1 Tsarina Maria Temryukovna (Мария Темрюковна; 1544-1569), as was Gwascheney 1 The corresponding monument amongst the Western Circassians (Adigeans) was built in 1957 in Friendship Square in Maikop, the republican capital, “in honour of the 400th anniversary of the ‘Military and Political Union’ between the Russian State and Circassia”. -

Maria Paleologina and the Il-Khanate of Persia. a Byzantine Princess in an Empire Between Islam and Christendom

MARIA PALEOLOGINA AND THE IL-KHANATE OF PERSIA. A BYZANTINE PRINCESS IN AN EMPIRE BETWEEN ISLAM AND CHRISTENDOM MARÍA ISABEL CABRERA RAMOS UNIVERSIDAD DE GRANADA SpaIN Date of receipt: 26th of January, 2016 Final date of acceptance: 12th of July, 2016 ABSTRACT In the 13th century Persia, dominated by the Mongols, a Byzantine princess, Maria Paleologina, stood out greatly in the court of Abaqa Khan, her husband. The Il-Khanate of Persia was then an empire precariously balanced between Islam, dominant in its territories and Christianity that was prevailing in its court and in the diplomatic relations. The role of Maria, a fervent Christian, was decisive in her husband’s policy and in that of any of his successors. Her figure deserves a detailed study and that is what we propose in this paper. KEYWORDS Maria Paleologina, Il-khanate of Persia, Abaqa, Michel VIII, Mongols. CapitaLIA VERBA Maria Paleologa, Ilkhanatus Persiae, Abaqa, Michael VIII, Mongoles. IMAGO TEMPORIS. MEDIUM AEVUM, XI (2017): 217-231 / ISSN 1888-3931 / DOI 10.21001/itma.2017.11.08 217 218 MARÍA ISABEL CABRERA RAMOS 1. Introduction The great expansion of Genghis Khan’s hordes to the west swept away the Islamic states and encouraged for a while the hopes of the Christian states of the East. The latter tried to ally themselves with the powerful Mongols and in this attempt they played the religion card.1 Although most of the Mongols who entered Persia, Iraq and Syria were shamanists, Nestorian Christianity exerted a strong influence among elites, especially in the court. That was why during some crucial decades for the history of the East, the Il-Khanate of Persia fluctuated between the consolidation of Christian influence and the approach to Islam, that despite the devastation brought by the Mongols in Persia,2 Iraq and Syria remained the dominant factor within the Il-khanate. -

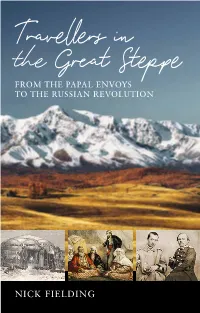

Nick Fielding

Travellers in the Great Steppe FROM THE PAPAL ENVOYS TO THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION NICK FIELDING “In writing this book I have tried to explain some of the historical events that have affected those living in the Great Steppe – not an easy task, as there is little study of this subject in the English language. And the disputes between the Russians and their neighbours and between the Bashkirs, the Kazakhs, the Turkomans, the Kyrgyz and the Kalmyks – not to mention the Djungars, the Dungans, the Nogai, the Mongols, the Uighurs and countless others – means that this is not a subject for the faint-hearted. Nonetheless, I hope that the writings referred to in this book have been put into the right historical context. The reasons why outsiders travelled to the Great Steppe varied over time and in themselves provide a different kind of history. Some of these travellers, particularly the women, have been forgotten by modern readers. Hopefully this book will stimulate you the reader to track down some of the long- forgotten classics mentioned within. Personally, I do not think the steppe culture described so vividly by travellers in these pages will ever fully disappear. The steppe is truly vast and can swallow whole cities with ease. Landscape has a close relationship with culture – and the former usually dominates the latter. Whatever happens, it will be many years before the Great Steppe finally gives up all its secrets. This book aims to provide just a glimpse of some of them.” From the author’s introduction. TRAVELLERS IN THE GREAT STEPPE For my fair Rosamund TRAVELLERS IN THE GREAT STEPPE From the Papal Envoys to the Russian Revolution NICK FIELDING SIGNAL BOOKS . -

Hijra and Forced Migration from Nineteenth-Century Russia to The

Cahiers du monde russe Russie - Empire russe - Union soviétique et États indépendants 41/1 | 2000 Varia Hijra and forced migration from nineteenth- century Russia to the Ottoman Empire A critical analysis of the Great Tatar emigration of 1860-1861 Brian Glyn Williams Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/monderusse/39 DOI: 10.4000/monderusse.39 ISSN: 1777-5388 Publisher Éditions de l’EHESS Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 2000 Number of pages: 79-108 ISBN: 2-7132-1353-3 ISSN: 1252-6576 Electronic reference Brian Glyn Williams, « Hijra and forced migration from nineteenth-century Russia to the Ottoman Empire », Cahiers du monde russe [Online], 41/1 | 2000, Online since 15 January 2007, Connection on 20 April 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/monderusse/39 ; DOI : 10.4000/monderusse.39 © École des hautes études en sciences sociales, Paris. BRIAN GLYN WILLIAMS HIJRA AND FORCED MIGRATION FROM NINETEENTH-CENTURY RUSSIA TO THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE A critical analysis of the Great Crimean Tatar emigration of 1860-1861 THE LARGEST EXAMPLES OF FORCED MIGRATIONS in Europe since the World War II era have involved the expulsion of Muslim ethnic groups from their homelands by Orthodox Slavs. Hundreds of thousands of Bulgarian Turks were expelled from Bulgaria by Todor Zhivkov’s communist regime during the late 1980s; hundreds of thousands of Bosniacs were cleansed from their lands by Republika Srbska forces in the mid-1990s; and, most recently, close to half a million Kosovar Muslims have been forced from their lands by Yugoslav forces in Kosovo in Spring of 1999. This process can be seen as a continuation of the “Great Retreat” of Muslim ethnies from the Balkans, Pontic rim and Caucasus related to the nineteenth-century collapse of Ottoman Muslim power in this region. -

The Caucasus.Pdf

NOTE. UJE ALEXAXDER B- was a captain in the Rwian dragoon gnarda. For his participation in the insurrection of 1825, he was sentenced to hnrd 1.t - - . - -- - ----"- - I THE DISTINGUISHED PFARRIOR-AUTHOR me Laucaaus. Shortly after his being restored to the rank of an officer, he was killed by the Ckcwsians, but his body waa never found. As a portrait of Beatoujef waa published at the had of his works, not with his name, bat with that of '<Mmlin&.** the Grand.---- Tlnbn-" M;nh=-r-*.,u*=. said .* - - 5 - AND THE GREAT EXILE. to the Czar: "PouwiU surely not dlow that people who have merited C,.n ha, hanged should be thua conspicuonsly exhibited." The Grand Duke possessed, in a high degreeJ the quality ofthose who, YI Voltaire have no mind-lir, the faciliq of making blmdem. up, ha. WITH TfIE MOST PROFOUND VENERATION. Mardinof, the h&d of the ciadetective police, whohaa mntedp.rn&iom to print the portrait of the author-soldier, was disgraced. THIS WORK IS DEDICATED, -- PBlTS1, DlJEZ, UDOD., C~APYIDB, AXn lrHW rPP-T, BLACPB-- iv COSTESTS. CONTENTS. T FAGB FAOX CHAPTER 111. CHAPTER VII. An Equcftrid Excursion on thc side of the Caspian Sea, by Bcstoujef- EXPLORATION OF TEE CAUCASUS. Fernerebe to the Caspian. .............. 39 /' The JIarch of the Ark -Prometheus-The Amazons of Herodotus-Expe& tion of the Argonauts-That of Alexander the Great-Mithridates-Strabo -Byzantius-Arabian Authors and their Knowledge of the Caucaus- CIX4PTER IV. Russian Princes-Invasions of the Mongols-Gengis-khan-Timour - MESATE. Missionaries-Genves Works on the Caucasus. ........ 93 T... -

Circassian Independence: Thoughts on the Current Political Situation of the Circassians

Circassian Independence: Thoughts on the Current Political Situation of the Circassians Amjad Jaimoukha The August 2008 war between Georgia and Russia is having and is slated to have profound and long-lasting effects on the political situation and attitudes in the whole of the Caucasus. One outcome that is of fundamental importance – and a source of great joy – to the overwhelming majority of Northwest Caucasians (Circassians=Adiga, Abkhaz-Abaza=Apswa, and Ubykh=Pakhy) in the Caucasus and diaspora is the recognition of Abkhazia’s independence by Russia (and a few days later also by Nicaragua and a number of internationally unrecognized entities). The ancient Abkhaz nation, which is steeped in tradition and classical history, seems to have taken yet another big step in the arduous path towards full independence. 1 The primordial will of a vigorous and lively nation has won yet another battle in the long war against the dark forces of hegemony and negation of the other. This exciting development has opened the door wide for the Circassians to openly express and co-ordinate their efforts to substantiate their demand for independence. Surely, if Russia could extend sovereign recognition to the 200,000 Abkhazians, then it would also be receptive to the justified demand of the more than one million Circassians in the Northwest Caucasus (and the multi-million strong Circassian diaspora) to consolidate and reunite their country ‘Circassia’, which had existed for millennia prior to Russian occupation in the 19th century, and to declare independence. 1 Those interested in gaining a perspective on Abkhaz history, and other issues, unadulterated by Georgian nationalist drivel can do worse than read Prof.