Sigur Rós: Reception, Borealism, and Musical Style

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 189.Pmd

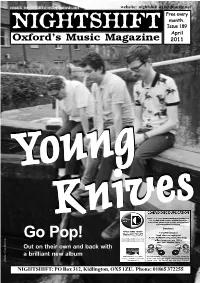

email: [email protected] NIGHTSHIFTwebsite: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every Oxford’s Music Magazine month. Issue 189 April 2011 YYYYYYoungoungoungoung KnivesKnivesKnivesKnives Go Pop! Out on their own and back with a brilliant new album photo: Cat Stevens NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net WILCO JOHNSON AND listings for the weekend, plus ticket DEACON BLUE are the latest details, are online at names added to this year’s www.oxfordjazzfestival.co.uk Cornbury Festival bill. The pair join already-announced headliners WITNEY MUSIC FESTIVAL returns James Blunt, The Faces and for its fifth annual run this month. Status Quo on a big-name bill that The festival runs from 24th April also includes Ray Davies, Cyndi through to 2nd May, featuring a Lauper, Bellowhead, Olly Murs, selection of mostly local acts across a GRUFF RHYS AND BELLOWHEAD have been announced as headliners The Like and Sophie Ellis-Bextor. dozen venues in the town. Amongst a at this year’s TRUCK FESTIVAL. Other new names on the bill are host of acts confirmed are Johnson For the first time Truck will run over three full days, over the weekend of prog-folksters Stackridge, Ben Smith and the Cadillac Blues Jam, 22nd-24th July at Hill Farm in Steventon. The festival will also enjoy an Montague & Pete Lawrie, Toy Phousa, Alice Messenger, Black Hats, increased capacity and the entire site has been redesigned to accommodate Hearts, Saint Jude and Jack Deer Chicago, Prohibition Smokers new stages. -

Volcanic Action and the Geosocial in Sigur Rós's “Brennisteinn”

Journal of Aesthetics & Culture ISSN: (Print) 2000-4214 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/zjac20 Musical aesthetics below ground: volcanic action and the geosocial in Sigur Rós’s “Brennisteinn” Tore Størvold To cite this article: Tore Størvold (2020) Musical aesthetics below ground: volcanic action and the geosocial in Sigur Rós’s “Brennisteinn”, Journal of Aesthetics & Culture, 12:1, 1761060, DOI: 10.1080/20004214.2020.1761060 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/20004214.2020.1761060 © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. Published online: 04 May 2020. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=zjac20 JOURNAL OF AESTHETICS & CULTURE 2020, VOL. 12, 1761060 https://doi.org/10.1080/20004214.2020.1761060 Musical aesthetics below ground: volcanic action and the geosocial in Sigur Rós’s “Brennisteinn” Tore Størvold Department of Musicology, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway ABSTRACT KEYWORDS This article presents a musicological and ecocritical close reading of the song “Brennisteinn” Sigur Rós; anthropocene; (“sulphur” or, literally, “burning rock”) by the acclaimed post-rock band Sigur Rós. The song— ecomusicology; ecocriticism; and its accompanying music video—features musical, lyrical, and audiovisual means of popular music; Iceland registering the turbulence of living in volcanic landscapes. My analysis of Sigur Rós’s music opens up a window into an Icelandic cultural history of inhabiting a risky Earth, a condition captured by anthropologist Gísli Pálsson’s concept of geosociality, which emerged from his ethnography in communities living with volcanoes. -

Jazz, Identity and Sound Design in a Melting Pot

ACADEMY OF MUSIC AND DRAMA Jazz, identity and sound design in a melting pot Lauri Kallio Independent Project (Degree Project), 15 HEC, Bachelor of Fine Arts in (Name of Program) Spring, 2019 Independent Project (Degree Project), 15 higher education credits Bachelor of Fine Arts in (Name of Program) Academy of Music and Drama, University of Gothenburg Spring, 2019 Author: Lauri Kallio Title: Jazz, identity and sound design in a melting pot Supervisor: Dr. Joel Eriksson Examiner: ABSTRACT In this piece of artistic research the author explores his musical toolbox and aesthetics for creating music. Finding compositional and music productional identity are also the main themes of this work. These aspects are being researched through the process creating new music. The author is also trying to build a bridge between his academic and informal studies over the years. The questions researched are about originality in composition and sound, and the challenges that occur during the working period. Key words: Jazz, Improvisation, Composition, Music Production, Ensemble, Free, Ambient 2 (34) Table of contents: 1. Introduction 1.1. Background 4 1.2. Goal and Questions 5 1.3. Method 6 2. Pre-recorded material 2.1.” 2147” 6 2.2. ”SAKIN” 7 2.3. ”BLE” 8 2.4. The selected elements 9 3. The compositions 3.1. “Mobile” 10 3.1.2. The rehearsing process 11 3.2. “ONEHE-274” 12 3.2.2. The rehearsing process 14 3.3. “TURBULENCE” 15 3.3.2. The rehearsing process 16 3.4. Rehearsing with electronics only 17 4. Conclusion 19 5. Afterword 20 6. -

Amiina Puzzle Mp3, Flac, Wma

amiina Puzzle mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Rock Album: Puzzle Country: Iceland Released: 2010 Style: Post Rock, Experimental MP3 version RAR size: 1913 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1146 mb WMA version RAR size: 1116 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 195 Other Formats: RA WAV DMF AU MP2 AHX APE Tracklist Hide Credits Ásinn 1 5:31 Bass – Kjartan Sveinsson 2 Over And Again 3:39 What Are We Waiting For? 3 Bass – Kjartan SveinssonCello – Kristín LárusdóttirDouble Bass – Borgar MagnasonViola – 5:26 Guðrún Hrund HarðardóttirViolin – Bjarni Frímann Bjarnason, Ingrid Karlsdóttir 4 Púsl 6:13 In The Sun 5 4:16 Double Bass – Borgar Magnason 6 Mambó 4:56 Sicsak 7 Bass – Kjartan SveinssonCello – Kristín LárusdóttirDouble Bass – Borgar MagnasonViola – 6:51 Guðrún Hrund HarðardóttirViolin – Bjarni Frímann Bjarnason, Ingrid Karlsdóttir Thoka 8 Vocals [Additional] – Bryndís Nielsen, Inga Harðardóttir, Jóhann Ágúst Jóhannsson, Kjartan 3:55 Sveinsson, Sigtryggur Baldursson* Companies, etc. Recorded At – Sundlaugin Studio Recorded At – Grundarstíg Recorded At – Brekkustíg Recorded At – Granda Mixed At – Sundlaugin Studio Mastered At – Sterling Sound Credits Layout, Design – Sólrún Sumarliðadóttir Mastered By – Greg Calbi Mixed By – Birgir Jón Birgisson, amiina Music By, Performer – amiina Photography By [Photographs] – Lilja Birgisdóttir Notes Recorded in Sundlaugin, Grundarstíg, Brekkustíg, Granda and JL. Mixed in Sundlaugin Studio. Mastered at Sterling Sound, NYC. Digipak packaging The catalog# only appears on the CD matrix and sticker Track 4 was called "Þristurinn", track 7 "Tvisturinn" on their self-released record "Re Minore" Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout: AMIINA5 *040415 Barcode (on sticker): 5 690351 110722 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Sound Of A shake 011, Puzzle (LP, shake 011, Amiina Handshake, Sound Of Germany 2011 SHAKE 011 Album) SHAKE 011 A Handshake Puzzle (CD, amiina5 amiina Amínamúsík Ehf. -

The Sound of Ruins: Sigur Rós' Heima and the Post

CURRENT ISSUE ARCHIVE ABOUT EDITORIAL BOARD ADVISORY BOARD CALL FOR PAPERS SUBMISSION GUIDELINES CONTACT Share This Article The Sound of Ruins: Sigur Rós’ Heima and the Post-Rock Elegy for Place ABOUT INTERFERENCE View As PDF By Lawson Fletcher Interference is a biannual online journal in association w ith the Graduate School of Creative Arts and Media (Gradcam). It is an open access forum on the role of sound in Abstract cultural practices, providing a trans- disciplinary platform for the presentation of research and practice in areas such as Amongst the ways in which it maps out the geographical imagination of place, music plays a unique acoustic ecology, sensory anthropology, role in the formation and reformation of spatial memories, connecting to and reviving alternative sonic arts, musicology, technology studies times and places latent within a particular environment. Post-rock epitomises this: understood as a and philosophy. The journal seeks to balance kind of negative space, the genre acts as an elegy for and symbolic reconstruction of the spatial its content betw een scholarly w riting, erasures of late capitalism. After outlining how post-rock’s accommodation of urban atmosphere accounts of creative practice, and an active into its sonic textures enables an ‘auditory drift’ that orients listeners to the city’s fragments, the engagement w ith current research topics in article’s first case study considers how formative Canadian post-rock acts develop this concrete audio culture. [ More ] practice into the musical staging of urban ruin. Turning to Sigur Rós, the article challenges the assumption that this Icelandic quartet’s music simply evokes the untouched natural beauty of their CALL FOR PAPERS homeland, through a critical reading of the 2007 tour documentary Heima. -

Development of Musical Ideas in Compositions by Tortoise

DEVELOPMENT OF MUSICAL IDEAS IN COMPOSITIONS BY TORTOISE Reiner Krämer Prologue For more than 25 years, the Chicago-based experimental rock band Tortoise has crossed over multiple popular music genres (ambient music, krautrock, dub, electronica, drums and bass, reggae, etc.) as well as different types of jazz music, and has made use of minimalist Western art music.1 The group is often labeled a pioneer of the »post-rock« genre. Allegedly, Simon Reynolds first used the term in his review of the album Hex by the English east Lon- don band Bark Psychosis (Reynolds 1994a) and shortly afterwards in his arti- cle »Shaking the Rock Narcotic« (Reynolds 1994b: 28-32). In connection to Tortoise he used »post-rock« in his review article of their 1996 album Mil- lions Now Living Will Never Die (Reynolds 1996). Reynolds describes music he labels as ›post-rock‹ where bands use guitars »in [non-rock] ways« to manipulate »timbre and texture rather than riff[s]« and »augment rock's basic guitar-bass-drums lineup with digital technology such as samplers and sequencers« (Reynolds 2017: 509). Most members of Tortoise act as multi- instrumentalists that play different combinations of instruments at different times. As Jeanette Leech (2017: 16) has stated, a typical Tortoise stage set- up can feature vibraphones, marimbas, two drum sets, and a multitude of synthesizers. With regards to the instrumental setup Leech draws up paral- lels with progressive rock of the 1970s but points to one decisive difference within the genres: »for Tortoise, the range of instrumentation [is] about creating mood, not showboating« (ibid.). -

Phonographic Performance Company of Australia Limited Control of Music on Hold and Public Performance Rights Schedule 2

PHONOGRAPHIC PERFORMANCE COMPANY OF AUSTRALIA LIMITED CONTROL OF MUSIC ON HOLD AND PUBLIC PERFORMANCE RIGHTS SCHEDULE 2 001 (SoundExchange) (SME US Latin) Make Money Records (The 10049735 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) 100% (BMG Rights Management (Australia) Orchard) 10049735 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) Music VIP Entertainment Inc. Pty Ltd) 10065544 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) 441 (SoundExchange) 2. (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) NRE Inc. (The Orchard) 100m Records (PPL) 777 (PPL) (SME US Latin) Ozner Entertainment Inc (The 100M Records (PPL) 786 (PPL) Orchard) 100mg Music (PPL) 1991 (Defensive Music Ltd) (SME US Latin) Regio Mex Music LLC (The 101 Production Music (101 Music Pty Ltd) 1991 (Lime Blue Music Limited) Orchard) 101 Records (PPL) !Handzup! Network (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) RVMK Records LLC (The Orchard) 104 Records (PPL) !K7 Records (!K7 Music GmbH) (SME US Latin) Up To Date Entertainment (The 10410Records (PPL) !K7 Records (PPL) Orchard) 106 Records (PPL) "12"" Monkeys" (Rights' Up SPRL) (SME US Latin) Vicktory Music Group (The 107 Records (PPL) $Profit Dolla$ Records,LLC. (PPL) Orchard) (SME US Latin) VP Records - New Masters 107 Records (SoundExchange) $treet Monopoly (SoundExchange) (The Orchard) 108 Pics llc. (SoundExchange) (Angel) 2 Publishing Company LCC (SME US Latin) VP Records Corp. (The 1080 Collective (1080 Collective) (SoundExchange) Orchard) (APC) (Apparel Music Classics) (PPL) (SZR) Music (The Orchard) 10am Records (PPL) (APD) (Apparel Music Digital) (PPL) (SZR) Music (PPL) 10Birds (SoundExchange) (APF) (Apparel Music Flash) (PPL) (The) Vinyl Stone (SoundExchange) 10E Records (PPL) (APL) (Apparel Music Ltd) (PPL) **** artistes (PPL) 10Man Productions (PPL) (ASCI) (SoundExchange) *Cutz (SoundExchange) 10T Records (SoundExchange) (Essential) Blay Vision (The Orchard) .DotBleep (SoundExchange) 10th Legion Records (The Orchard) (EV3) Evolution 3 Ent. -

The Search for Consistent Intonation: an Exploration and Guide for Violoncellists

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2017 THE SEARCH FOR CONSISTENT INTONATION: AN EXPLORATION AND GUIDE FOR VIOLONCELLISTS Daniel Hoppe University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2017.380 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Hoppe, Daniel, "THE SEARCH FOR CONSISTENT INTONATION: AN EXPLORATION AND GUIDE FOR VIOLONCELLISTS" (2017). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 98. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/98 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

Stan Magazynu Caĺ†Oĺıäƒ Lp Cd Sacd Akcesoria.Xls

CENA WYKONAWCA/TYTUŁ BRUTTO NOŚNIK DOSTAWCA ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - AT FILLMORE EAST 159,99 SACD BERTUS ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - AT FILLMORE EAST (NUMBERED 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - BROTHERS AND SISTERS (NUMBE 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - EAT A PEACH (NUMBERED LIMIT 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - IDLEWILD SOUTH (GOLD CD) 129,99 CD GOLD MOBILE FIDELITY ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - THE ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND (N 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY ASIA - ASIA 179,99 SACD BERTUS BAND - STAGE FRIGHT (HYBRID SACD) 89,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY BAND, THE - MUSIC FROM BIG PINK (NUMBERED LIMITED 89,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY BAND, THE - THE LAST WALTZ (NUMBERED LIMITED EDITI 179,99 2 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY BASIE, COUNT - LIVE AT THE SANDS: BEFORE FRANK (N 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY BIBB, ERIC - BLUES, BALLADS & WORK SONGS 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BIBB, ERIC - JUST LIKE LOVE 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BIBB, ERIC - RAINBOW PEOPLE 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BIBB, ERIC & NEEDED TIME - GOOD STUFF 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BIBB, ERIC & NEEDED TIME - SPIRIT & THE BLUES 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BLIND FAITH - BLIND FAITH 159,99 SACD BERTUS BOTTLENECK, JOHN - ALL AROUND MAN 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 CAMEL - RAIN DANCES 139,99 SHMCD BERTUS CAMEL - SNOW GOOSE 99,99 SHMCD BERTUS CARAVAN - IN THE LAND OF GREY AND PINK 159,99 SACD BERTUS CARS - HEARTBEAT CITY (NUMBERED LIMITED EDITION HY 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY CHARLES, RAY - THE GENIUS AFTER HOURS (NUMBERED LI 99,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY CHARLES, RAY - THE GENIUS OF RAY CHARLES (NUMBERED 129,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY -

Rock Music Is a Genre of Popular Music That Entered the Mainstream in the 1950S

Rock music is a genre of popular music that entered the mainstream in the 1950s. It has its roots in 1940s and 1950s rock and roll, rhythm and blues, country music and also drew on folk music, jazz and classical music. The sound of rock often revolves around the electric guitar, a back beat laid down by a rhythm section of electric bass guitar, drums, and keyboard instruments such as Hammond organ, piano, or, since the 1970s, synthesizers. Along with the guitar or keyboards, saxophone and blues-style harmonica are sometimes used as soloing instruments. In its "purest form", it "has three chords, a strong, insistent back beat, and a catchy melody."[1] In the late 1960s and early 1970s, rock music developed different subgenres. When it was blended with folk music it created folk rock, with blues to create blues-rock and with jazz, to create jazz-rock fusion. In the 1970s, rock incorporated influences from soul, funk, and Latin music. Also in the 1970s, rock developed a number of subgenres, such as soft rock, glam rock, heavy metal, hard rock, progressive rock, and punk rock. Rock subgenres that emerged in the 1980s included new wave, hardcore punk and alternative rock. In the 1990s, rock subgenres included grunge, Britpop, indie rock, and nu metal. A group of musicians specializing in rock music is called a rock band or rock group. Many rock groups consist of an electric guitarist, lead singer, bass guitarist, and a drummer, forming a quartet. Some groups omit one or more of these roles or utilize a lead singer who plays an instrument while singing, sometimes forming a trio or duo; others include additional musicians such as one or two rhythm guitarists or a keyboardist. -

The Acoustic City

The Acoustic City The Acoustic City MATTHEW GANDY, BJ NILSEN [EDS.] PREFACE Dancing outside the city: factions of bodies in Goa 108 Acoustic terrains: an introduction 7 Arun Saldanha Matthew Gandy Encountering rokesheni masculinities: music and lyrics in informal urban public transport vehicles in Zimbabwe 114 1 URBAN SOUNDSCAPES Rekopantswe Mate Rustications: animals in the urban mix 16 Music as bricolage in post-socialist Dar es Salaam 124 Steven Connor Maria Suriano Soft coercion, the city, and the recorded female voice 23 Singing the praises of power 131 Nina Power Bob White A beautiful noise emerging from the apparatus of an obstacle: trains and the sounds of the Japanese city 27 4 ACOUSTIC ECOLOGIES David Novak Cinemas’ sonic residues 138 Strange accumulations: soundscapes of late modernity Stephen Barber in J. G. Ballard’s “The Sound-Sweep” 33 Matthew Gandy Acoustic ecology: Hans Scharoun and modernist experimentation in West Berlin 145 Sandra Jasper 2 ACOUSTIC FLÂNERIE Stereo city: mobile listening in the 1980s 156 Silent city: listening to birds in urban nature 42 Heike Weber Joeri Bruyninckx Acoustic mapping: notes from the interface 164 Sonic ecology: the undetectable sounds of the city 49 Gascia Ouzounian Kate Jones The space between: a cartographic experiment 174 Recording the city: Berlin, London, Naples 55 Merijn Royaards BJ Nilsen Eavesdropping 60 5 THE POLITIcs OF NOISE Anders Albrechtslund Machines over the garden: flight paths and the suburban pastoral 186 3 SOUND CULTURES Michael Flitner Of longitude, latitude, and -

Contents Welome 2 Conference Programme 4 Abstracts 24 Panels

17th Biennial Conference of IASPM | Bridge Over Troubled Waters: Challenging Orthodoxies | Gijón 2013 Contents Welome 2 Conference programme 4 Abstracts 24 Panels 133 iaspm2013.espora.es 1 17th Biennial Conference of IASPM | Bridge Over Troubled Waters: Challenging Orthodoxies | Gijón 2013 Dear IASPM Conference Delegates, Welcome to Gijón, and to the 17th biennial IASPM Conference “Bridge over Troubled Waters”, a conference with participants from all over the world with the aim of bridging a gap between disciplines, perspectives and cultural contexts. We have received more than 500 submissions, of which some 300 made it to the programme, together with four outstanding keynote speakers. This Conference consolidates the increasing participation of Spanish delegates in previous conferences since the creation of the Spanish branch of IASPM in 1999, and reinforces the presence of Popular Music Studies at the Spanish universities and research groups. The University of Oviedo is one of the pioneer institutions in the Study of Popular Music in Spain; since the late nineties, this field of study is constantly growing due to the efforts of scholars and students that approach this repertoire from an interdisciplinary perspective. As for the place that hosts the conference, Gijón is an industrial city with an important music scene. I wouldn´t call it the Spanish Liverpool, but some critics called it the Spanish Seattle because it was an important place for the development of “noise music” in Spain during the 1990s. The venue, Laboral, is an exponent of the architecture of the dictatorship. Finished in 1956, it was conceived as a school for war orphans to learn a trade and in 2007 it was remodeled to become a “city for culture”.