Where's My Village?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Release Univision Communications Inc

PRESS RELEASE UNIVISION COMMUNICATIONS INC. Investor Contact: Media Contact: Adam Shippee Bobby Amirshahi (646) 560-4992 646-560-4902 [email protected] [email protected] Univision Communications Inc. Univision Communications Inc. UNIVISION COMMUNICATIONS INC. TO HOST Q2 2018 CONFERENCE CALL ON AUGUST 9, 2018 NEW YORK – AUGUST 2, 2018 – Univision Communications Inc. (UCI), the leading media company serving Hispanic America, will conduct a conference call to discuss its second quarter 2018 financial results at 11:00 a.m. ET/8:00 a.m. PT on Thursday, August 9, 2018. A press release summarizing its second quarter 2018 financial results will be available on UCI’s website at investors.univision.net/financial-reports/quarterly-reports before market opens on Thursday, August 9, 2018. To participate in the conference call, please dial (866) 858-0462 (within U.S.) or (360) 562-9850 (outside U.S.) fifteen minutes prior to the start of the call and provide the following pass code: 5289787. A playback of the conference call will be available beginning at 2:00 p.m. ET, Thursday, August 9, 2018, through Thursday, August 23, 2018. To access the playback, please dial (855) 859-2056 (within U.S.) or (404) 537-3406 (outside U.S.) and enter reservation number 5289787. About Univision Communications Inc. Univision Communications Inc. (UCI) is the leading media company serving Hispanic America. The Company, a chief content creator in the U.S., includes Univision Network, one of the top networks in the U.S. regardless of language and the most-watched Spanish-language broadcast television network in the country, available in approximately 88% of U.S. -

The Effects and Behaviours of Home Alone Situation by Latchkey Children

American Journal of Nursing Science 2015; 4(4): 207-211 Published online July 21, 2015 (http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ajns) doi: 10.11648/j.ajns.20150404.19 ISSN: 2328-5745 (Print); ISSN: 2328-5753 (Online) The Effects and Behaviours of Home Alone Situation by Latchkey Children J. Rajalakshmi 1, P. Thanasekaran 2 1Medical-Science Department, Ambo University, Ambo, Ethiopia, East Africa 2Medical-Science Department, Wollega University, Nekemte, Ethiopia, East Africa Email address: [email protected] (J. Rajalakshmi), [email protected] (P. Thanasekaran) To cite this article: J. Rajalakshmi, P. Thanasekaran. The Effects and Behaviours of Home Alone Situation by Latchkey Children. American Journal of Nursing Science . Vol. 4, No. 4, 2015, pp. 207-211. doi: 10.11648/j.ajns.20150404.19 Abstract: Economic and social pressures are forcing more parents into the workplace at a time when children appear to most need adult guidance and supervision. These children, in turn, face a growing number of problems such as physical and sexual abuse, crime and delinquency, depression and suicide, drug and alcohol abuse, emotional and behavioral problems, learning difficulties, school attendance problems, domestic violence, pregnancy, abortion, and venereal disease. Many "latchkey" children experience stressful and even dangerous situations without ready access to adult guidance and support. It is estimated that as many as 10 million children care for themselves before or after school. Many latchkey kids begin their self-care responsibilities at about 8 years of age. Keywords: Introduction, History, Statistics, Literatures, Exports Talk, Effects on Children, Parents Tips, Kids Safe 1. Introduction How do parents provide supervision for their school age under a mat (or some other object) at the rear door to the children when they work? School age children are sometimes property. -

18734 Homework 3

18734 Homework 3 Released: October 7, 2016 Due: 12 noon Eastern, 9am Pacific, Oct 21, 2016 1 Legalease [20 points] In this question, you will convert a simple policy into the Legalease language. To review the Legalease language and its grammar, refer to the lecture slides from September 28. You may find it useful to go through a simple example provided in Section III.C in the paper Bootstrapping Privacy Compliance in Big Data Systems 1. A credit company CreditX has the following information about its customers: • Name • Address • PhoneNumber • DateOfBirth • SSN All this information is organized under a common table: AccountInfo. Their privacy policy states the following: We will not share your SSN with any third party vendors, or use it for any form of advertising. Your phone number will not be used for any purpose other than notifying you about inconsistencies in your account. Your address will not be used, except by the Legal Team for audit purposes. Convert this statement into Legalease. You may use the attributes: DataType, UseForPur- pose, AccessByRole. Relevant attribute-values for DataType are AccountInfo, Name, Address, PhoneNumber, DateOfBirth, and SSN. Useful attribute-values for UseForPurpose are ThirdPar- tySharing, Advertising, Notification and Audit. One attribute-value for AccessByRole is LegalTeam. 1http://www.andrew.cmu.edu/user/danupam/sen-guha-datta-oakland14.pdf 1 2 AdFisher [35=15+20 points] For this part of the homework, you will work with AdFisher. AdFisher is a tool written in Python to automate browser based experiments and run machine learning based statistical analyses on the collected data. 2.1 Installation AdFisher was developed around 2014 on MacOS. -

Univision Communications Inc to Acquire Digital Media Assets from Gawker Media for $135 Million

UNIVISION COMMUNICATIONS INC TO ACQUIRE DIGITAL MEDIA ASSETS FROM GAWKER MEDIA FOR $135 MILLION Acquisition of Digital Assets will Reinforce UCI’s Digital Strategy and is Expected to Increase Fusion Media Group’s Digital Reach to Nearly 75 Million Uniques, Building on Recent Investments in FUSION, The Root and The Onion NEW YORK – AUGUST 18, 2016 – Univision Communications Inc. (UCI) today announced it has entered into an agreement to acquire digital media assets as part of the bankruptcy proceedings of Gawker Media Group, Inc. and related companies that produce content under a series of original brands that reach nearly 50 million readers per month, according to comScore. UCI will acquire the digital media assets for $135 million, subject to certain adjustments, and these assets will be integrated into Fusion Media Group (FMG), the division of UCI that serves the young, diverse audiences that make up the rising American mainstream. The deal, which will be accounted for as an asset purchase, includes the following digital platforms, Gizmodo, Jalopnik, Jezebel, Deadspin, Lifehacker and Kotaku. UCI will not be operating the Gawker.com site. With this strategic acquisition, FMG’s digital reach is expected rise to nearly 75 million uniques, or 96 million uniques when including its extended network. The acquisition will further enrich FMG’s content offerings across key verticals including iconic platforms focused on technology (Gizmodo), car culture (Jalopnik), contemporary women’s interests (Jezebel) and sports (Deadspin), among others. The deal builds on UCI’s recently announced creation of FMG and investments in FUSION, The Root and The Onion, which includes The A.V. -

$10,000,000 Says Hillary Wins

$10,000,000 Says Hillary Wins Haim Saban wants to put Clinton in the White House and take Univision public BY DEVIN LEONARD PHOTOGRAPH BY JEFF MINTON aim Saban, the billionaire chairman of Univision some of whom he said were rapists, Univision has taken an a garbage man and a disciplinarian. “I of the company’s affiliates that followed Communications, America’s largest Spanish-language adversarial stance. Nine days after Trump’s comments, the know,” he says, sitting in front of a large because so many were watching. media company, flew to Jerusalem in his private jet network canceled its plans to broadcast his Miss USA pageant. picture window through which you can Afterward, Saban says, News Corp. H on Sept. 29 to attend the funeral of his friend Shimon Trump filed a $500 million breach of contract lawsuit, alleg- see the late afternoon sun reddening the Chairman Rupert Murdoch wanted to buy Peres, Israel’s former prime minister. It was an event attended by ing Saban was interfering to benefit Clinton. (The suit was lush grounds outside. “You’re looking at his production company. “I said, ‘Bubbie, numerous world leaders. Saban gave one of them a lift: former settled confidentially.) The next month, Trump had Jorge me and thinking, ‘You were in charge of forget about it, I don’t need your money. U.S. President Bill Clinton. In Saban’s telling, it wasn’t a big deal. Ramos, Univision’s leading news anchor, tossed out of a news discipline?’ Yes, I was.” (It’s so not hard Let’s create a partnership. -

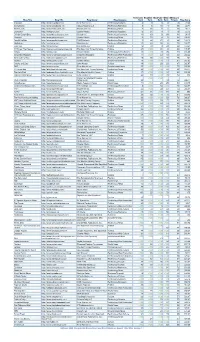

Blog Title Blog URL Blog Owner Blog Category Technorati Rank

Technorati Bloglines BlogPulse Wikio SEOmoz’s Blog Title Blog URL Blog Owner Blog Category Rank Rank Rank Rank Trifecta Blog Score Engadget http://www.engadget.com Time Warner Inc. Technology/Gadgets 4 3 6 2 78 19.23 Boing Boing http://www.boingboing.net Happy Mutants LLC Technology/Marketing 5 6 15 4 89 33.71 TechCrunch http://www.techcrunch.com TechCrunch Inc. Technology/News 2 27 2 1 76 42.11 Lifehacker http://lifehacker.com Gawker Media Technology/Gadgets 6 21 9 7 78 55.13 Official Google Blog http://googleblog.blogspot.com Google Inc. Technology/Corporate 14 10 3 38 94 69.15 Gizmodo http://www.gizmodo.com/ Gawker Media Technology/News 3 79 4 3 65 136.92 ReadWriteWeb http://www.readwriteweb.com RWW Network Technology/Marketing 9 56 21 5 64 142.19 Mashable http://mashable.com Mashable Inc. Technology/Marketing 10 65 36 6 73 160.27 Daily Kos http://dailykos.com/ Kos Media, LLC Politics 12 59 8 24 63 163.49 NYTimes: The Caucus http://thecaucus.blogs.nytimes.com The New York Times Company Politics 27 >100 31 8 93 179.57 Kotaku http://kotaku.com Gawker Media Technology/Video Games 19 >100 19 28 77 216.88 Smashing Magazine http://www.smashingmagazine.com Smashing Magazine Technology/Web Production 11 >100 40 18 60 283.33 Seth Godin's Blog http://sethgodin.typepad.com Seth Godin Technology/Marketing 15 68 >100 29 75 284 Gawker http://www.gawker.com/ Gawker Media Entertainment News 16 >100 >100 15 81 287.65 Crooks and Liars http://www.crooksandliars.com John Amato Politics 49 >100 33 22 67 305.97 TMZ http://www.tmz.com Time Warner Inc. -

Huzzah to the Double Helix! It's International DNA Day | Lifehacker

Huzzah To The Double Helix! It’s International DNA Day | L... http://www.lifehacker.com.au/2013/04/huzzah-to-the-double-h... Business Insider Gizmodo Kotaku Lifehacker PopSugar BellaSugar FabSugar ShopStyle Log In Register Life Work IT Pro RECENTLY ON KOTAKU RECENTLY ON KOTAKU Robin Has A Point In These Hilarious Conference Or Not, We’ll Cherish Superhero Texts These E3 Nintendo Memes Forever HOME Huzzah To The Double Helix! It’s International DNA Day CHRIS JAGER YESTERDAY 9:30 AM Share 5858 Discuss 22 Today is International DNA Day, which this year commemorates 60 years since the scientific paper A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid was first published. Here’s what some of Australia’s leading scientists SUBSCRIBE have to say about the importance of the discovery… CONTACT DNA picture from Shutterstock Sixty years ago to the day, James Watson and Francis Crick published a revolutionary paper on the Like Lifehacker Australia 5,616 Followers structure of Deoxyribonucleic acid; the molecular key to all living things otherwise known as DNA. A Follow Lifehacker Australia 11,734 Followers century after Gregor Mendel first began messing about with peas, the final piece of the genetic puzzle had been slotted into place. Subscribe to all stories 15,269 Followers To mark this historic occasion, several Australian scientists have released statements in which they Australian stories 1,859 Followers basically wax lyrical about the wonders of DNA — what better way to start your morning? (And if you’re wondering what the Lifehacker angle is, the answer is quite simple: when someone smarter than you has something to say, it’s usually worth listening!) REGULARS LIFE Professor Suzanne Cory, President of the Australian Academy of Science: Sell Your Stuff And Get Some Extra Cash This Weekend The discovery of the structure of DNA by James Watson and Francis Crick was an epic moment in the history of science. -

Univision Communications Inc. Announces 2018 First Quarter Results

PRESS RELEASE UNIVISION COMMUNICATIONS INC. Page 1 of 14 UNIVISION COMMUNICATIONS INC. ANNOUNCES 2018 FIRST QUARTER RESULTS TOTAL REVENUE OF $684.2 MILLION COMPARED TO $692.6 MILLION NET INCOME OF $47.4 MILLION COMPARED TO NET INCOME OF $58.1 MILLION ADJUSTED OIBDA OF $244.9 MILLION COMPARED TO $272.6 MILLION ADJUSTED CORE OIBDA OF $236.2 MILLION COMPARED TO $236.4 MILLION NEW YORK, NY – May 9, 2018 – Univision Communications Inc. (the “Company”), the leading media company serving Hispanic America, today announced financial results for the first quarter ended March 31, 2018. First Quarter 2018 Results Compared to First Quarter 2017 Results • Total revenue decreased 1.2% to $684.2 million from $692.6 million. Total core revenue1 decreased 1.2% to $672.9 million from $681.1 million. • Net income attributable to Univision Communications Inc.2 was $47.4 million compared to $58.1 million. • Adjusted OIBDA3 decreased 10.2% to $244.9 million from $272.6 million. Adjusted Core OIBDA4 decreased 0.1% to $236.2 million from $236.4 million. • Interest expense decreased 11.7% to $96.9 million from $109.7 million. The Company continued to deleverage and has reduced total indebtedness, net of cash and cash equivalents by $76.2 million for the first quarter of 2018. “Univision delivered approximately $684 million in revenue, $47 million in net income, and $245 million in Adjusted OIBDA in the first quarter. We continued to reduce our debt and year over year interest expense,” said Randy Falco, President and CEO of Univision Communications Inc. “Even with a leading portfolio of Spanish- language linear assets, a growing digital portfolio and a strong and time-tested relationship with our audience, we recognize that accelerating changes at Univision now is as important as ever given the rapid evolution in the media sector. -

Preparing-Your-Child-To-Be-A-Latchkey-Kid.Pdf

All over the US, children are going home after school and spending time alone until their parents get home from work. This is what a latchkey kid is. The term came about because they have their own key, usually on a chain hung from their neck, to unlock their home each day when they’re done with school. They typically have no adult supervision for two to three hours each evening while they wait for their parents to come home. There are more than four million grade-school-aged latchkey kids because there are a lot of dual-income parents and single parents in the workforce today. But this number is down from its high in the 80s when over half of all children were latchkey kids. It’s very difficult to find affordable childcare for this age group. However, before you choose to let your child become a latchkey kid, there are many things to consider - such as the laws in your area, whether your child is mature enough, and your own financial and emotional situation. Latchkey Kids and the Law If you’re considering letting your child become a latchkey kid, then you need to find out what the law is in your state, city, and county. For the most part, allowing a child to stay home before the age of 8 is not recommended or even legal today. It was done in the past with great regularity but now the laws have changed the rules for parents. Most professionals agree that children between ages 8 and 10 shouldn’t be home alone for more than a couple of hours. -

Something Cool After School

Technical Assistance Paper Number 1 The Qualities of Excellent School-Age Care For generations, children nearing the vast majority of two-parent park and recreation centers, some the end of their school day have households require both parents to in activity or child care centers. Some found their minds wandering from work outside the home. Nearly half of cater to children up to age 10; others their classroom books and their all households with children are run provide environments specifically teachers’ voices. With delicious by a single parent. For many children, designed for older children. While tension they have rustled in their family social structures that once some focus all their activities on a seats and eyed the minute hand of created safe and constructive central theme such as the arts, the big round wall clock, waiting for recreational opportunities have athletics, or community building, that last mechanical clink, followed evaporated. others develop highly varied agendas by the r-r-r-ring of the day’s-end School-age care programs seek to that take into account the full range bell. Then, like Fred Flintstone redress these concerns. The term of children’s interests and surfing down his rockasaurus’s “school-age care” encompasses a characteristics. back, they’ve dashed out of the gamut of services offered before and Typically, an enrolled child spends classroom into what they consider after school operating hours for anywhere from 15 to 20 hours a to be their “real” lives. Riding bikes children between ages 5 and 14. week— the equivalent of two full and writing poems. -

© 2015 Scientific American He First Time It Happened, Christine* Was Only Seven Years Old

© 2015 Scientific American he first time it happened, Christine* was only seven years old. Her mother’s live-in boyfriend sexually as- saulted her, beginning an abusive relationship that Victims of sexual assault in lasted more than two years. When a friend of the childhood face a higher risk family figured out what was going on, the friend in- formed Christine’s mom, who refused to believe it, of future abuse. Research despite her daughter’s confirmation. Soon afterward, is suggesting ways of a social services worker confronted the family, and Christine’s abuser fled. Christine never saw the man again, but it was not the end of her experience with sexual trauma. She T lived in a neighborhood with a high crime rate. She Breaking T was a latchkey kid, who was often unsupervised and left to fend for herself. Sexual abuse seemed to follow her. the In high school, she was gang-raped at a party. Years later, after she joined the military, she met a man whom she thought she could trust. They dated for a short period, but just when she decided to end the relationship, he forced himself on her. Cycle Now, at 38, Christine is finally in a solid, healthy relationship. But she still has her struggles. Although she has seen counselors on By Sushma Subramanian and off over the years, she continues to have nightmares related to her attacks and has difficulty trusting people. Christine is one of 84 women involved in a long-term study of the impact of childhood sexual abuse, led by University of South- ern California psychologist Penelope Trickett. -

Leading Television Broadcasters Name John Hane President of Spectrum Consortium

LEADING TELEVISION BROADCASTERS NAME JOHN HANE PRESIDENT OF SPECTRUM CONSORTIUM BALTIMORE, Maryland and IRVING, Texas – January 31, 2018 – Spectrum Co, LLC (“Spectrum Co”), the ATSC 3.0 spectrum consortium founded by Sinclair Broadcast Group, Inc. (Nasdaq: SBGI) (“Sinclair”) and Nexstar Media Group, Inc. (Nasdaq: NXST) (“Nexstar”) and for which Univision Local Media, Inc. (“Univision”) has signed a Memorandum of Understanding to join, announced today that John Hane has been named President. Mr. Hane most recently served as a partner in the Washington, D.C. office of Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP, a global law firm with a leading technology practice, where he primarily focused on counseling clients in telecom, broadcast and technology sectors and was deeply involved in matters related to the development and regulatory approval of ATSC 3.0 (“NextGen”). A “go-to” advisor on spectrum matters, before joining Pillsbury Mr. Hane led a large satellite and wireless network development group. He is the inventor or co-inventor of four patents related to wireless and satellite spectrum. Mr. Hane’s appointment reflects the consortium’s shared goal of promoting spectrum utilization, innovation and monetization by advancing the adoption of the ATSC 3.0 transmission standard across the broadcast industry. As President of Spectrum Co., he will oversee the development of the newly- formed entity as it pursues advanced nationwide business opportunities made available by the NextGen standard and aggregation of spectrum bandwidth. John Hane commented, “The consortium’s strong commitment to innovation and the advancement of the local broadcast television industry through future digital technology capabilities, were strong factors in attracting me to this position.