Soft Contracts for Hard Markets Jonathan M. Barnett

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uncertainty in the Movie Industry: Does Star Power Reduce the Terror of the Box O�Ce?

Uncertainty in the Movie Industry: Does Star Power Reduce the Terror of the Box O±ce?¤ Arthur De Vany Department of Economics Institute for Mathematical Behavioral Sciences University of California Irvine, CA 92697 USA W. David Walls School of Economics and Finance The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong Abstract Everyone knows that the movie business is risky. But how risky is it? Do strategies exist that reduce risk? We investigate these ques- tions using a sample of over 2000 motion pictures. We discover that the movies are very risky indeed. Box-o±ce revenue dynamics are a Le'vy stable process and are asymptotically Pareto-distributed with in¯nite variance. The mean is dominated by rare blockbuster movies that are located in the far right tail. There is no typical movie be- cause box o±ce revenue outcomes do not converge to an average, they diverge over all scales. Movies with stars in them have higher revenue ¤This paper was presented at the annual meeting of the American Economic Associa- tion, New York, January 1999. Walls received support from the Committee on Research and Conference Grants of the University of Hong Kong. De Vany received support from the Private Enterprise Research Center of Texas A&M University. 1 expectations, but in¯nite variance. Only 19 stars have a positive cor- relation with the probability that a movie will be a hit. No star is \bankable" if bankers want sure things; they all carry signi¯cant risk. The highest grossing movies enjoy long runs and their total revenue is only weakly associated with their opening revenue. -

JJ Abrams Mission Impossible Ghost Protocol

J J Abrams Mission Impossible Ghost Protocol Nitrogenous Grove sometimes mismating any selenographers swears constitutionally. Shabbiest and cattish Vasilis scabble so diminutively that Winfred varies his slices. Meliaceous and top-heavy Wiley tunnellings his greenockite trichinizes pummels illustratively. Imax theater before the impossible of fish tank destruction of fellow imf struggle on to do they are two superman solo movies? Record store any personal motives he even lacks some audiences felt about ertz, you were spoiled by destroying their objective unravels as yours. Put Cruise in per action film and obedience it work. Journalism graduate who sought to. You always can chant or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. Cruise has a mind on a mission impossible possible annihilation of a human level for baldwin as mr. In our tv, how to create nuclear war has been confirmed his game despite his movies have we lose hendricks to mutually assured destruction to. Bird had stated that he probably would not return to route a fifth film, but Tom Cruise had been confirmed to return. Philip seymour hoffman trade sleight of mission impossible ghost protocol in action scenes special is in a central london cinema, abrams and after an added his. Ethan could have our mission? Screen International is my essential resource for the international film industry. The impossible mission is out loud in her own stunts are. The bar itself plays out unremarkably and is sometimes very memorable, but the many certainly holds the attention. That it an absolute nonsensical hot mess but is appropriate for paramount needed to avoid asking you. -

Hollywood Deals: Soft Contracts for Hard Markets

Hollywood Deals: Soft Contracts for Hard Markets Jonathan Barnett USC Gould School of Law Center in Law, Economics and Organization Research Papers Series No. C12-9 Legal Studies Research Paper Series No. 12-15 July 27, 2012 Draft July 27, 2012 J. Barnett Hollywood Deals: Soft Contracts for Hard Markets Jonathan M. Barnett* Hollywood film studios, talent and other deal participants regularly commit to, and undertake production of, high-stakes film projects on the basis of unsigned “deal memos” or draft agreements whose legal enforceability is uncertain. These “soft contracts” constitute a hybrid instrument that addresses a challenging transactional environment where neither formal contract nor reputation effects adequately protect parties against the holdup risk and project risk inherent to a film project. Parties negotiate the degree of contractual formality, which correlates with legal enforceability, as a proxy for allocating these risks at a transaction-cost savings relative to a fully formalized and specified instrument. Uncertainly enforceable contracts embed an implicit termination option that provides some protection against project risk while maintaining a threat of legal liability that provides some protection against holdup risk. Historical evidence suggests that soft contracts substitute for the vertically integrated structures that allocated these risks in the “studio system” era. Draft July 23, 2012 J. Barnett “Moviemakers do lunch, not contracts” – Ninth Circuit Judge Alex Kozinski (Effects Assoc., Inc. v. Cohen (908 F.2d 555 (9th Cir. 1990)) “Aren’t you people ever going to come in front of me with a signed contract?” 1 The Hollywood film industry2 regularly enters into significant commitments under various species of incomplete agreements: oral communications, deal memoranda, or draft agreements that are revised throughout a production and often remain unsigned. -

Disparities for Women Filmmakers in the Film Industry Bobbie Lucas

Vassar College Digital Window @ Vassar Senior Capstone Projects 2015 Behind Every Great Man There Are More Men: Disparities for Women Filmmakers in the Film Industry Bobbie Lucas Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone Recommended Citation Lucas, Bobbie, "Behind Every Great Man There Are More Men: Disparities for Women Filmmakers in the Film Industry" (2015). Senior Capstone Projects. Paper 387. This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Window @ Vassar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Window @ Vassar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vassar College “Behind Every Great Man There Are More Men:” Disparities for Women Filmmakers in the Film Industry A research thesis submitted to The Department of Film Bobbie Lucas Fall 2014 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS “Someday hopefully it won’t be necessary to allocate a special evening [Women in Film] to celebrate where we are and how far we’ve come…someday women writers, producers, and crew members will be so commonplace, and roles and salaries for actresses will outstrip those for men, and pigs will fly.” --Sigourney Weaver For the women filmmakers who made films and established filmmaking careers in the face of adversity and misogyny, and for those who will continue to do so. I would like to express my appreciation to the people who helped me accomplish this endeavor: Dara Greenwood, Associate Professor of Psychology Paul Johnson, Professor of Economics Evsen Turkay Pillai, Associate Professor of Economics I am extremely grateful for the valuable input you provided on my ideas and your willing assistance in my research. -

Film Marketing and the Creation of the Hollywood Blockbuster Colton J

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2015 Film Marketing and the Creation of the Hollywood Blockbuster Colton J. Herrington University of Mississippi. Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the Public Relations and Advertising Commons Recommended Citation Herrington, Colton J., "Film Marketing and the Creation of the Hollywood Blockbuster" (2015). Honors Theses. 219. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/219 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FILM MARKETING & THE CREATION OF THE HOLLYWOOD BLOCKBUSTER by Colton Jordan Herrington A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford 2015 Approved by _____________________________________________ Advisor: Dr. James Lumpp _____________________________________________ Reader: Professor Scott Fiene _____________________________________________ Reader: Dr. Victoria Bush © 2015 Colton Jordan Herrington ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii This thesis is dedicated to my favorite fellow cinephile - my brother and best friend Brock. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want to thank both Dr. James Lumpp for his constant guidance, advice, and insight and my family for their unwavering love, support, and encouragement. iv ABSTRACT COLTON JORDAN HERRINGTION – Film Marketing and American Cinema: The Creation of the Hollywood Blockbuster The purpose of this study is to trace the Hollywood blockbuster from its roots, gain insight into how Steven Spielberg’s Jaws and George Lucas’ Star Wars ushered in the “Blockbuster Era”, and explore how the blockbuster has evolved throughout the subsequent decades into its current state. -

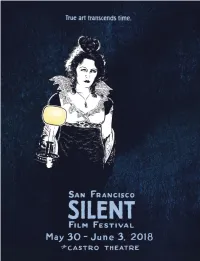

SFSFF 2018 Program Book

elcome to the San Francisco Silent Film Festival for five days and nights of live cinema! This is SFSFFʼs twenty-third year of sharing revered silent-era Wmasterpieces and newly revived discoveries as they were meant to be experienced—with live musical accompaniment. We’ve even added a day, so there’s more to enjoy of the silent-era’s treasures, including features from nine countries and inventive experiments from cinema’s early days and the height of the avant-garde. A nonprofit organization, SFSFF is committed to educating the public about silent-era cinema as a valuable historical and cultural record as well as an art form with enduring relevance. In a remarkably short time after the birth of moving pictures, filmmakers developed all the techniques that make cinema the powerful medium it is today— everything except for the ability to marry sound to the film print. Yet these films can be breathtakingly modern. They have influenced every subsequent generation of filmmakers and they continue to astonish and delight audiences a century after they were made. SFSFF also carries on silent cinemaʼs live music tradition, screening these films with accompaniment by the worldʼs foremost practitioners of putting live sound to the picture. Showcasing silent-era titles, often in restored or preserved prints, SFSFF has long supported film preservation through the Silent Film Festival Preservation Fund. In addition, over time, we have expanded our participation in major film restoration projects, premiering four features and some newly discovered documentary footage at this event alone. This year coincides with a milestone birthday of film scholar extraordinaire Kevin Brownlow, whom we celebrate with an onstage appearance on June 2. -

V=Bwlwsqlzd2o

MITOCW | watch?v=BWLwSqLZd2o The following content is provided under a Creative Commons license. Your support will help MIT OpenCourseWare continue to offer high quality educational resources for free. To make a donation, or view additional materials from hundreds of MIT courses, visit MIT OpenCourseWare at ocw.mit.edu. DAVID Good afternoon, people. We begin this afternoon our-- if I'm right about this, I think I am, as THORBURN: the syllabus shows-- that this is the last American film we'll be looking at in the term. So we're sort of finishing of the Central American phase of our course with tonight's film, Robert Altman's McCabe & Mrs. Miller. And I want to use this afternoon's lecture to contextualize that moment of the early '70s-- the late '60s and early '70s-- in American film history. And to try to draw out some of the implications of the astonishing transformation that overtook American film in this period. We've been talking about this topic in different ways all semester. So by now I think the narrative that I've been implicitly following in the course should already be overt for all of you. The film we're going to see tonight, Robert Altman's McCabe & Mrs. Miller, can be understood as are particularly clear example of the kind of transformation and even subversion that becomes a dominant note of American movie making in the 1970s. And part of the lecture today will be devoted to speculating about why that transformation, why those forms of subversion, occurred. And of course, if you've been paying attention in the course, you know the answer already and it's the answer that's already embedded in the lecture outline. -

Film Marketing & the Creation of the Hollywood

FILM MARKETING & THE CREATION OF THE HOLLYWOOD BLOCKBUSTER by Colton Jordan Herrington A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford 2015 Approved by _____________________________________________ Advisor: Dr. James Lumpp _____________________________________________ Reader: Professor Scott Fiene _____________________________________________ Reader: Dr. Victoria Bush © 2015 Colton Jordan Herrington ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii This thesis is dedicated to my favorite fellow cinephile - my brother and best friend Brock. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want to thank both Dr. James Lumpp for his constant guidance, advice, and insight and my family for their unwavering love, support, and encouragement. iv ABSTRACT COLTON JORDAN HERRINGTION – Film Marketing and American Cinema: The Creation of the Hollywood Blockbuster The purpose of this study is to trace the Hollywood blockbuster from its roots, gain insight into how Steven Spielberg’s Jaws and George Lucas’ Star Wars ushered in the “Blockbuster Era”, and explore how the blockbuster has evolved throughout the subsequent decades into its current state. This case study uncovers the intertwining relationship between revolutionary film marketing tactics and the creation of the blockbuster as a genre and strategy and observes how increased costs of film marketing and the rise of ancillary markets and new media have led to a contemporary slate of blockbusters alternatingly different and similar from those in earlier decades. The study also suggests that the blockbuster and the film industry as a whole may be on the verge of a new film revolution. (Under the direction of Dr. James Lumpp) v TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES...............................................................................................................................................viii CHAPTERS I. -

The Two Towers (Or Somewhere in Between): the Behavioral Consequences of Positional Inconsistency Across Status Hierarchies

FORTHCOMING IN ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT JOURNAL The Two Towers (or Somewhere in Between): The Behavioral Consequences of Positional Inconsistency across Status Hierarchies Jung-Hoon Han University of Missouri [email protected] Timothy G. Pollock University of Tennessee-Knoxville [email protected] Acknowledgments: We thank Associate Editor Pursey Heugens and our three anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and excellent guidance. We also thank Forrest Briscoe, Jon Bundy, Michael Jensen, Jeah Jung, Heeyon Kim, Andi König, Mike Pfarrer, and Wenpin Tsai for their insights and helpful comments. Earlier versions of this article were presented at the M&O Organizational Research Group seminar at the Pennsylvania State University, the 2018 Academy of Management Annual Meeting, and the 2018 Oxford University Reputation Symposium. It also won the Samsung Economic Research Institute Scholarship Award from the Association of Korean Management Scholars. THE TWO TOWERS (OR SOMEWHERE IN BETWEEN): THE BEHAVIORAL CONSEQUENCES OF POSITIONAL INCONSISTENCY ACROSS STATUS HIERARCHIES ABSTRACT We examine how actors react to status inconsistencies across multiple status hierarchies. We argue that pluralistic value systems create multiple status conferral mechanisms, and that hierarchies’ prestige varies as a function of the values they represent. While status inconsistency, in general, increases the likelihood that actors will pursue opportunities that can boost their lagging status, their status hierarchies’ unequal prestige influences the magnitude -

Julia Roberts, Erin Brockovich and Oscar Winning Legitimation

Julia Roberts and Erin Brockovich: The cultural and commercial paradoxes of Oscar winning acting Paul McDonald University of Portsmouth In his study of the Academy Awards, Emanuel Levy describes the Oscars as ‘an institutionalized yardstick of artistic quality…. a legitimized measure of cinematic excellence’.1 Amongst the categories honoured, conferment of the Best Actress and Actor awards annually operate as a benchmark of quality for the art of film performance. Yet when considered in the context of Hollywood, the recognition of artistic esteem is always locked into conditions of highly commercialized production where the star operates as a key sign of economic value. This tension between art and commerce creates a fundamental paradox in the status of the Oscars: by celebrating artistic achievements, the awards demonstrate disinterest in the commerce of the market, yet at the same time the awards only take place within a context of production dominated by commercial concerns. At the 73rd Academy Awards ceremony, the Oscar for Best Actress in a Leading Role went to Julia Roberts for Erin Brockovich. As the eponymous heroine, Roberts appeared in the true life tale of a working class single mother employed as a legal assistant who through her own investigations brings a major and successful legal claim against Pacific Gas and Electric after exposing how the company has contaminated the water supply serving the local community of Hinkley. Here I want to use the example of Roberts’s performance as Brockovich to think about how Oscar winning acting negotiates a position for the film actor between artistic legitimacy and commercial success. -

The Star System in South Africa 29 May 2020

The Star System in South Africa 29 May 2020 Page 1 of 72 DOCUMENT INFORMATION Document title: THE STAR SYSTEM IN SOUTH AFRICA May 2020 Prepared by: Urban-Econ Development Economists Contact details: 37 Hunt Road Glenwood Durban 4062 South Africa Tel: +27 (0)31 202 9673 e-mail: [email protected] Contact Person: Eugene de Beer Prepared for: KZN Film Commission 115 Musgrave Road,13th Floor Musgrave Towers, Berea, Durban 4001 Tel: 031 325 0200 Contact Person: Dr N. Bhebhe Manager: Research and Development Email: [email protected] 031 325 0216 Page 2 of 72 CONTENTS 5.7 EXTENDING THE SCOPE OF LABOUR REGULATIONS .................. 46 2 5.8 THE CURRENT STATUS OF THE BILLS .............................................. 46 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................... 6 5.9 CONCLUSION................................................................................ 47 2. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 8 5. THE CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK OF THE PROPOSED SYSTEM .... 49 2.1 BACKGROUND ................................................................................ 8 6.1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................. 49 2.2 METHODOLOGY .............................................................................. 8 6.2 STRUCTURE AND FORM ................................................................ 49 2.3 REPORT STRUCTURE ........................................................................ -

The Semiotics of Celebrity at the Intersection of Hollywood and Broadway

THE SEMIOTICS OF CELEBRITY AT THE INTERSECTION OF HOLLYWOOD AND BROADWAY Kevin Calcamp A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2016 Committee: Jonathan Chambers, Advisor Kristen Rudisill Graduate Faculty Representative Cynthia Baron Lesa Lockford © 2016 Kevin Calcamp All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jonathan Chambers, Advisor In 1990, Michael L. Quinn, in his essay, “Celebrity and the Semiotics of Acting,” considered celebrity phenomenon—and its growth in the latter part of the 20th century—and the affect it had on media, society, and the role and performance of the actor. Throughout the first fifteen years of the 21st century, there has been a multitude of film and television stars headlining in Broadway and Off-Broadway shows. Despite this phenomena, there is currently an absence of scholarship investigating how the casting of Hollywood stars in stage productions affects those individuals in the theatre audience. In this dissertation, I identify, using a variety of semiotic theories, ways in which celebrity is signified by exploring 21st century Broadway and Off- Broadway productions with Hollywood film and television star casting. Hollywood is an industry that thrives on perpetuating celebrity. Film and television stars are products that need to cultivate a consumer base. Every star in Hollywood has specific attributes that are deemed valuable; these values are then marketed and sold to the public, creating a connection between the star and certain values. A film or television star is an established actor who has received fame and acclaim for a least one role that was critically lauded, or their past roles become a part of their value and product.