Soft Contracts for Hard Markets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feature Films

NOMINATIONS AND AWARDS IN OTHER CATEGORIES FOR FOREIGN LANGUAGE (NON-ENGLISH) FEATURE FILMS [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] [* indicates win] [FLF = Foreign Language Film category] NOTE: This document compiles statistics for foreign language (non-English) feature films (including documentaries) with nominations and awards in categories other than Foreign Language Film. A film's eligibility for and/or nomination in the Foreign Language Film category is not required for inclusion here. Award Category Noms Awards Actor – Leading Role ......................... 9 ........................... 1 Actress – Leading Role .................... 17 ........................... 2 Actress – Supporting Role .................. 1 ........................... 0 Animated Feature Film ....................... 8 ........................... 0 Art Direction .................................... 19 ........................... 3 Cinematography ............................... 19 ........................... 4 Costume Design ............................... 28 ........................... 6 Directing ........................................... 28 ........................... 0 Documentary (Feature) ..................... 30 ........................... 2 Film Editing ........................................ 7 ........................... 1 Makeup ............................................... 9 ........................... 3 Music – Scoring ............................... 16 ........................... 4 Music – Song ...................................... 6 .......................... -

Compare Results

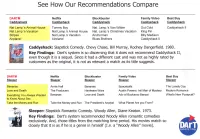

See How Our Recommendations Compare DARTM BestCaddvshackCaddyshackBuy AnchormanCaddvshackNat.BlockbusterBluesTommyNatCaddvshackAirplane!NetflixII Lamp.'sLamp.'sLamp.CaddyshackOutFamilyCaddvshackKingBillyBrothersBoyColdMadisonPin'sVanChristmasVideoAnimalVacationWilderII HouseVacation CaddvshackNat Lamp.'s VacationAirplane!Stripes Nat Lamp.'s Animal House Caddyshack: Slapstick Comedy. Chevy Chase, Bill Murray, Rodney Dangerfield. 1980. Key Findings: Dart's system is so discerning that it does not recommend Caddyshack II, even though it is a sequel. Since it had a different cast and was not as highly rated by customers as the original, it is not as relevant a match as its title suggests. DARTM AustinAdvSpaceballsSleeperFamilyWhatBlockbusterTheLoveHardwareBananasofPresident'sandPlanetPowers:BuckarooAnnieVideoTheSleeperTakeNetflixBananasDeathWarsWhat'sTheBestSleeperModernProducersAretheHallLonelyIntiBuyAnalystyouMoneyBanzaiNewManRomanceFrom?GuyPussycat?ofandMysteryRun SleepertoLoveKnowandAboutDeathSex Take the Money and Run EverythingBananas You Always Wanted Sleeper: Slapstick Romantic Comedy. Woody Allen, Diane Keaton. 1973. Key Findings: Dart's system recommended Woody Allen romantic comedies exclusively. And, chose titles from the matching time period. His movies match so closely that it is as if he is a genre in himself (I.e. a "Woody Allen" movie). DARTM WhereFamilyTearsRamboBestRamboTheofEaglesBeastVideoBuyIIItheTheCobraCommandoRockyOnMissingNetflixBlockbusterRamboRambo:IronIIISunDeadlyDogsEagleDareIVIIIinFirstofActionGroundWarBlood -

Motion Picture Posters, 1924-1996 (Bulk 1952-1996)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt187034n6 No online items Finding Aid for the Collection of Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Processed Arts Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Elizabeth Graney and Julie Graham. UCLA Library Special Collections Performing Arts Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Collection of 200 1 Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Descriptive Summary Title: Motion picture posters, Date (inclusive): 1924-1996 Date (bulk): (bulk 1952-1996) Collection number: 200 Extent: 58 map folders Abstract: Motion picture posters have been used to publicize movies almost since the beginning of the film industry. The collection consists of primarily American film posters for films produced by various studios including Columbia Pictures, 20th Century Fox, MGM, Paramount, Universal, United Artists, and Warner Brothers, among others. Language: Finding aid is written in English. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Performing Arts Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections. -

Tom Hanks Halle Berry Martin Sheen Brad Pitt Robert Deniro Jodie Foster Will Smith Jay Leno Jared Leto Eli Roth Tom Cruise Steven Spielberg

TOM HANKS HALLE BERRY MARTIN SHEEN BRAD PITT ROBERT DENIRO JODIE FOSTER WILL SMITH JAY LENO JARED LETO ELI ROTH TOM CRUISE STEVEN SPIELBERG MICHAEL CAINE JENNIFER ANISTON MORGAN FREEMAN SAMUEL L. JACKSON KATE BECKINSALE JAMES FRANCO LARRY KING LEONARDO DICAPRIO JOHN HURT FLEA DEMI MOORE OLIVER STONE CARY GRANT JUDE LAW SANDRA BULLOCK KEANU REEVES OPRAH WINFREY MATTHEW MCCONAUGHEY CARRIE FISHER ADAM WEST MELISSA LEO JOHN WAYNE ROSE BYRNE BETTY WHITE WOODY ALLEN HARRISON FORD KIEFER SUTHERLAND MARION COTILLARD KIRSTEN DUNST STEVE BUSCEMI ELIJAH WOOD RESSE WITHERSPOON MICKEY ROURKE AUDREY HEPBURN STEVE CARELL AL PACINO JIM CARREY SHARON STONE MEL GIBSON 2017-18 CATALOG SAM NEILL CHRIS HEMSWORTH MICHAEL SHANNON KIRK DOUGLAS ICE-T RENEE ZELLWEGER ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER TOM HANKS HALLE BERRY MARTIN SHEEN BRAD PITT ROBERT DENIRO JODIE FOSTER WILL SMITH JAY LENO JARED LETO ELI ROTH TOM CRUISE STEVEN SPIELBERG CONTENTS 2 INDEPENDENT | FOREIGN | ARTHOUSE 23 HORROR | SLASHER | THRILLER 38 FACTUAL | HISTORICAL 44 NATURE | SUPERNATURAL MICHAEL CAINE JENNIFER ANISTON MORGAN FREEMAN 45 WESTERNS SAMUEL L. JACKSON KATE BECKINSALE JAMES FRANCO 48 20TH CENTURY TELEVISION LARRY KING LEONARDO DICAPRIO JOHN HURT FLEA 54 SCI-FI | FANTASY | SPACE DEMI MOORE OLIVER STONE CARY GRANT JUDE LAW 57 POLITICS | ESPIONAGE | WAR SANDRA BULLOCK KEANU REEVES OPRAH WINFREY MATTHEW MCCONAUGHEY CARRIE FISHER ADAM WEST 60 ART | CULTURE | CELEBRITY MELISSA LEO JOHN WAYNE ROSE BYRNE BETTY WHITE 64 ANIMATION | FAMILY WOODY ALLEN HARRISON FORD KIEFER SUTHERLAND 78 CRIME | DETECTIVE -

February 2018 at BFI Southbank Events

BFI SOUTHBANK EVENTS LISTINGS FOR FEBRUARY 2018 PREVIEWS Catch the latest film and TV alongside Q&As and special events Preview: The Shape of Water USA 2017. Dir Guillermo del Toro. With Sally Hawkins, Michael Shannon, Doug Jones, Octavia Spencer. Digital. 123min. Courtesy of Twentieth Century Fox Sally Hawkins shines as Elisa, a curious woman rendered mute in a childhood accident, who is now working as a janitor in a research center in early 1960s Baltimore. Her comfortable, albeit lonely, routine is thrown when a newly-discovered humanoid sea creature is brought into the facility. Del Toro’s fascination with the creature features of the 50s is beautifully translated here into a supernatural romance with dark fairy tale flourishes. Tickets £15, concs £12 (Members pay £2 less) WED 7 FEB 20:30 NFT1 Preview: Dark River UK 2017. Dir Clio Barnard. With Ruth Wilson, Mark Stanley, Sean Bean. Digital. 89min. Courtesy of Arrow Films After the death of her father, Alice (Wilson) returns to her family farm for the first time in 15 years, with the intention to take over the failing business. Her alcoholic older brother Joe (Stanley) has other ideas though, and Alice’s return conjures up the family’s dark and dysfunctional past. Writer-director Clio Barnard’s new film, which premiered at the BFI London Film Festival, incorporates gothic landscapes and stunning performances. Tickets £15, concs £12 (Members pay £2 less) MON 12 FEB 20:30 NFT1 Preview: You Were Never Really Here + extended intro by director Lynne Ramsay UK 2017. Dir Lynne Ramsay. With Joaquin Phoenix, Ekaterina Samsonov, Alessandro Nivola. -

2017 Lincoln Community Foundation Annual Report 2017 OVERVIEW

2017 Lincoln Community Foundation Annual Report 2017 OVERVIEW “There seemed to be nothing to see; no fences, no creeks or trees, no hills or fields. If there was a road, I could not make it out in the faint starlight. There was nothing but land: not a country at all, but the material out of which countries are made.” Willa Cather, My Antonia, 1918 The Lincoln Community Foundation found We have inherited the grit and wisdom of our TO HELP BUILD A GREAT CITY; TO ways to support the inspiring opportunities in our ancestors who launched this state over 150 years NURTURE, HARNESS AND DIRECT THAT community: ago, built a land grant university referenced by ENERGY, IS THE ASPIRATION OF THE others as the Harvard on the Prairie, constructed a • In honor of the state’s sesquicentennial, a gift state of the art Capitol during the depression that LINCOLN COMMUNITY FOUNDATION. was made for the creation of the Gold Star now houses the only Unicameral in the country. Families Memorial. Visit the beautiful black Lincoln is the envy of cities across the USA with our granite monument at Antelope Park. one public school district. We could go on and on. • Supported the release of the latest Lin- We have tackled great challenges and embraced Barbara Bartle Tom Smith coln Vital Signs report at a summit en- marvelous opportunities. President Chair of the Board couraging citizens to “step up” to the P r o s p e r L i n c o l n c o m m u n i t y a g e n d a . -

Brian Tufano BSC Resume

BRIAN TUFANO BSC - Director of Photography FEATURE FILM CREDITS Special Jury Prize for Outstanding Contribution To British Film and Television - British Independent Film Awards 2002 Award for Outstanding Contribution To Film and Television - BAFTA 2001 EVERYWHERE AND NOWHERE Director: Menhaj Huda. Starring Art Malik, Amber Rose Revah, Adam Deacon, Producers: Menhaj Huda, Sam Tromans and Stella Nwimo. Stealth Films. ADULTHOOD Director: Noel Clarke Starring Noel Clarke, Adam Deacon, Red Mandrell, Producers: George Isaac, Damian Jones And Scarlett Johnson Limelight MY ZINC BED Director: Anthony Page Starring Uma Thurman, Jonathan Pryce, and Producer: Tracy Scofield Paddy Considine Rainmark Films/HBO I COULD NEVER BE YOUR WOMAN Director: Amy Heckerling Starring Michelle Pfeiffer and Paul Rudd Producer: Philippa Martinez, Scott Rudin Paramount Pictures KIDULTHOOD Director: Menhaj Huda Starring Aml Ameen, Adam Deacon Producer: Tim Cole Red Mandrell and Jamie Winstone Stealth Films/Cipher Films ONCE UPON A TIME IN Director: Shane Meadows THE MIDLANDS Producer: Andrea Calderwood Starring Robert Carlyle, Rhys Ifans, Kathy Burke. Ricky Tomlinson and Shirley Henderson Slate Films / Film Four LAST ORDERS Director: Fred Schepisi Starring: Michael Caine, Bob Hoskins, Producers: Rachel Wood, Elizabeth Robinson Tom Courtenay, Helen Mirren, Ray Winstone Scala Productions LATE NIGHT SHOPPING Director: Saul Metzstein Luke De Woolfson, James Lance, Kate Ashfield, Producer: Angus Lamont. Enzo Cilenti andShauna MacDonald Film Four Intl / Ideal World Films BILLY ELLIOT Director: Steven Daldry Julie Walters, Gary Lewis, Jamie Draven and Jamie Bell Producers: Jon Finn and Gregg Brenman. Working Title Films/Tiger Aspect Pictures BBC/Arts Council Film. 4929 Wilshire Blvd., Ste. 259 Los Angeles, CA 90010 ph 323.782.1854 fx 323.345.5690 [email protected] BRIAN TUFANO BSC - Director of Photography WOMEN TALKING DIRTY Director: Coky Giedroyc Helena Bonham-Carter, Gina McKee Producers: David Furnish and Polly Steele James Purefoy, Jimmy Nesbitt, Richard Wilson Petunia Productions. -

Set in Scotland a Film Fan's Odyssey

Set in Scotland A Film Fan’s Odyssey visitscotland.com Cover Image: Daniel Craig as James Bond 007 in Skyfall, filmed in Glen Coe. Picture: United Archives/TopFoto This page: Eilean Donan Castle Contents 01 * >> Foreword 02-03 A Aberdeen & Aberdeenshire 04-07 B Argyll & The Isles 08-11 C Ayrshire & Arran 12-15 D Dumfries & Galloway 16-19 E Dundee & Angus 20-23 F Edinburgh & The Lothians 24-27 G Glasgow & The Clyde Valley 28-31 H The Highlands & Skye 32-35 I The Kingdom of Fife 36-39 J Orkney 40-43 K The Outer Hebrides 44-47 L Perthshire 48-51 M Scottish Borders 52-55 N Shetland 56-59 O Stirling, Loch Lomond, The Trossachs & Forth Valley 60-63 Hooray for Bollywood 64-65 Licensed to Thrill 66-67 Locations Guide 68-69 Set in Scotland Christopher Lambert in Highlander. Picture: Studiocanal 03 Foreword 03 >> In a 2015 online poll by USA Today, Scotland was voted the world’s Best Cinematic Destination. And it’s easy to see why. Films from all around the world have been shot in Scotland. Its rich array of film locations include ancient mountain ranges, mysterious stone circles, lush green glens, deep lochs, castles, stately homes, and vibrant cities complete with festivals, bustling streets and colourful night life. Little wonder the country has attracted filmmakers and cinemagoers since the movies began. This guide provides an introduction to just some of the many Scottish locations seen on the silver screen. The Inaccessible Pinnacle. Numerous Holy Grail to Stardust, The Dark Knight Scottish stars have twinkled in Hollywood’s Rises, Prometheus, Cloud Atlas, World firmament, from Sean Connery to War Z and Brave, various hidden gems Tilda Swinton and Ewan McGregor. -

Uncertainty in the Movie Industry: Does Star Power Reduce the Terror of the Box O�Ce?

Uncertainty in the Movie Industry: Does Star Power Reduce the Terror of the Box O±ce?¤ Arthur De Vany Department of Economics Institute for Mathematical Behavioral Sciences University of California Irvine, CA 92697 USA W. David Walls School of Economics and Finance The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong Abstract Everyone knows that the movie business is risky. But how risky is it? Do strategies exist that reduce risk? We investigate these ques- tions using a sample of over 2000 motion pictures. We discover that the movies are very risky indeed. Box-o±ce revenue dynamics are a Le'vy stable process and are asymptotically Pareto-distributed with in¯nite variance. The mean is dominated by rare blockbuster movies that are located in the far right tail. There is no typical movie be- cause box o±ce revenue outcomes do not converge to an average, they diverge over all scales. Movies with stars in them have higher revenue ¤This paper was presented at the annual meeting of the American Economic Associa- tion, New York, January 1999. Walls received support from the Committee on Research and Conference Grants of the University of Hong Kong. De Vany received support from the Private Enterprise Research Center of Texas A&M University. 1 expectations, but in¯nite variance. Only 19 stars have a positive cor- relation with the probability that a movie will be a hit. No star is \bankable" if bankers want sure things; they all carry signi¯cant risk. The highest grossing movies enjoy long runs and their total revenue is only weakly associated with their opening revenue. -

LIHI at Home

LIHIat home 2013 Ernestine Anderson Place Grand Opening! On February 8th, LIHI held the Grand and a classroom. Opening of Ernestine Anderson Place in Ernestine Anderson Place is named Seattle’s Central District. Ernestine Anderson in honor of legendary jazz singer Ernestine Place features Anderson, an international star from permanent Seattle’s Central Area and graduate of housing linked Garfield High. In a career spanning more with supportive than five decades, she has recorded over services for 45 30 albums. She has sung at Carnegie Hall, homeless seniors, the Kennedy Center, the Monterey Jazz including 17 Festival, as well as at jazz festivals all over veterans, as well the world. as housing for 15 Ernestine Anderson Place is built green low-income seniors. according to Washington State Evergreen The building Standards and designed with long term features generous durability as a priority. The building community space features energy efficient insulation and fan for residents, systems and uses low VOC materials, including a library Energy-Star appliances, and dual-flush with computers, toilets throughout. Ernestine Anderson an exercise room, Place is a non-smoking facility, helping continued on page 3 Vote Each Day in May and Help LIHI Win $250,000 to House Homeless Veterans! Vote daily in May to help us house experiencing homelessness in King County veterans. You can help LIHI win $250,000 alone. With your votes, we’ll win $250,000 to House Homeless Veterans by voting to help build and rehab 50 apartments to assist local Veterans transitioning out of Veteran Thomas English and son live at on Facebook. -

GILBERT J. ARENAS, JR., an Individual, Plaintiff, V. SHED MEDIA

Case 2:11-cv-05279-DMG -PJW Document 19 Filed 08/01/11 Page 1 of 33 Page ID #:160 1 SHEPPARD, MULLIN, RICHTER & HAMPTON LLP A Limited Liability Partnership 2 Including Professional Corporations JAMES E. CURRY, Cal. Bar No. 115769 3 [email protected] VALERIE E. ALTER, Cal. Bar No. 239905 4 [email protected] 1901 Avenue of the Stars, Suite 1600 5 Los Angeles, California 90067-6017 Telephone: 310-228-3700 6 Facsimile: 310-228-3701 7 Attorneys for Defendant SHED IVMDIA US INC. 8 9 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 10 CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 11 12 GILBERT J. ARENAS, JR., an Case No. LACV11-5279 DMG (MRWX) individual, 13 DEFENDANT SHED MEDIA US INC.'S Plaintiff, 14 (1) NOTICE OF MOTION AND V. SPECIAL MOTION TO STRIKE 15 PLAINTIFF'S RIGHT OF SHED MEDIA US INC,. a Delaware PUBLICITY CLAIMS 16 coiporation; LAURA GOVAN, an PURSUANT TO CAL. CODE individual; and DOES 1 through 10, CIV. PROC. § 425.16; 17 inclusive, (2) MEMORANDUM OF POINTS 18 Defendants. AND AUTHORITIES; 19 (3) DECLARATION OF ALEX DEMYANENKO; 20 (4) DECLARATION OF SCOTT 21 ACORD; AND 22 (5) DECLARATION OF VALERIE E. ALTER 23 Hearing Date: August 29, 2011 24 Time: 10:00 a.m. Courtroom: 7 25 [Proposed Order Lodged Concurrently 26 Herewith] 27 [Complaint Filed: June 23, 20111 28 W02-WEST:IVEA2\ 403690466.4 Case 2:11-cv-05279-DMG -PJW Document 19 Filed 08/01/11 Page 2 of 33 Page ID #:161 1 TO THE ABOVE-CAPTIONED COURT AND TO PLAINTIFF AND HIS 2 COUNSEL OF RECORD: 3 PLEASE TAKE NOTICE that on Monday, August 29, 2011, at 10:00 a.m., or 4 as soon as possible thereafter as counsel can be heard in Courtroom 7 of the United 5 States Courthouse, 312 North Spring Street, Los Angeles, California 90012, before 6 the Honorable Dolly M. -

Sundayiournal

STANDING STRONG FOR 1,459 DAYS — THE FIGHT'S NOT OVER YET JULY 11-17, 1999 THE DETROIT VOL. 4 NO. 34 75 CENTS S u n d a yIo u r n a l PUBLISHED BY LOCKED-OUT DETROIT NEWSPAPER WORKERS ©TDSJ JIM WEST/Special to the Journal Nicholle Murphy’s support for her grandmother, Teamster Meka Murphy, has been unflagging. Marching fourward Come Tuesday, it will be four yearsstrong and determined. In this editionOwens’ editorial points out the facthave shown up. We hope that we will since the day in July of 1995 that ofour the Sunday Journal, co-editor Susanthat the workers are in this strugglehave contracts before we have to put Detroit newspaper unions were forcedWatson muses on the times of happiuntil the end and we are not goingtogether any another anniversary edition. to go on strike. Although the companess and joy, in her Strike Diarywhere. on On Pages 19-22 we show offBut four years or 40, with your help, nies tried mightily, they never Pagedid 3. Starting on Page 4, we putmembers the in our annual Family Albumsolidarity and support, we will be here, break us. Four years after pickingevents up of the struggle on the record.and also give you a glimpse of somestanding of strong. our first picket signs, we remainOn Page 10, locked-out worker Keiththe far-flung places where lawn signs— Sunday Journal staff PAGE 10 JULY 11 1999 Co-editors:Susan Watson, Jim McFarlin --------------------- Managing Editor: Emily Everett General Manager: Tom Schram Published by Detroit Sunday Journal Inc.