Las Positas College Feasibility Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Student Handbook 7X8.5 V3.Indd

2019-2020 2018-19 Mission Statement Las Positas College is an inclusive learning-centered institution providing educational opportunities and support for completion of students’ transfer, degree, basic skills, career-technical, and retraining goals. Vision Statement Las Positas College strives to be California’s premier Community College, setting the standard through opportunities for developing knowledge, skills, values, and abilities that foster engaged and contributing members of the society. Values Statement Las Positas College thrives as a collaborative teaching and learning community committed to integrity and excellence by: 1. Encouraging and celebrating lifelong learning 2. Responding to the needs of the ever-changing workplace 3. Demonstrating civic, social and environmental responsibility 4. Promoting ethical behavior, tolerance and mutual respect in a diverse community 5. Fostering a climate of discovery, creativity and personal development 6. Holding firm to the belief that each of us makes an astonishing difference TABLE OF CONTENTS WELCOME TO LAS POSITAS COLLEGE! ..................................4 Get On Track And Transfer! Get Started! EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITIES ..............................................42 STUDENT EQUITY AND PREPARE TO TRANSFER ..........................................................44 ACHIEVEMENT PROGRAM (SEAP) .......................................... 5 GUARANTEED TRANSFER PROGRAMS ....................................45 NEW STUDENT CHECKLIST .....................................................6 -

Honors Inventory

Honors Inventory Institution Method Class Size Coordinator Compensation Other Info American River College Stand Alone 20 Yes 20% reassigned time used to be 40%, this is first time Cerritos College Combination 30 Yes 60% reassigned time at 60% trying to grow one extra hour per week or four Cerro Coso Community College Certified/Contract Process Same as Non Honors Yes $2800 stipend honors contracts (sub proj) time is split between two full time faculty + stipend to seminar College of San Mateo Stand Alone Seminars - 2 hrs. 20 Yes 35% reassigned time faculty Load + p/t coordinator fully funded Crafton Hills College Combination Same as Non Honors Yes 50% load thru Title V grant (100 students) East Los Angeles College Stand Alone & Combination 25 Yes 50% reassigned time El Camino College Stand Alone & Combination 30 Yes 50% reassigned time 2 positions Foothill College Stand Alone & Combination Same as Non Honors Yes 10% overload 40% re-assigned prev. $25K in Scholarships from private Fresno City College Stand Alone Same as Non Honors Yes 40% reassigned time donor in process of changing to stand Irvine Valley College Combination 15 (English)/ 20 (Others) Yes 30% reassigned time alone LA Mission College ? ? Yes 20% reassigned time/stipend Las Positas College Combination Same as Non Honors Yes 20% reassigned time time is split between two full time Los Medanos College Stand Alone & Combination 20 Yes 65% reassigned time faculty Moorepark College Stand Alone & Combination Same as Non Honors Yes 10% reassigned time Pierce College Stand Alone 25 -

Total Number

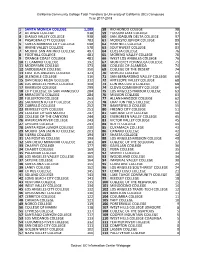

California Community College Total Transfers to University of California (UC) Campuses Year 2017-2018 1 SANTA MONICA COLLEGE 1,289 58 RIO HONDO COLEGE 98 2 DE ANZA COLLEGE 938 59 FOLSOM LAKE COLLEGE 97 3 DIABLO VALLEY COLLEGE 938 60 SAN JOAQUIN DELTA COLLEGE 97 4 PASADENA CITY COLLEGE 783 61 MODESTO JUNIOR COLLEGE 89 5 SANTA BARBARA CITY COLLEGE 648 62 HARTNELL COLLEGE 85 6 IRVINE VALLEY COLLEGE 578 63 SOUTHWEST COLLEGE 83 7 MOUNT SAN ANTINIO COLLEGE 497 64 CUESTA COLLEGE 76 8 FOOTHILL COLLEGE 481 65 MORENO VALLEY COLLEGE 76 9 ORANGE COAST COLLEGE 481 66 WEST LOS ANGELES COLLEGE 76 10 EL CAMINO COLLEGE 392 67 MONTEREY PENINSULA COLLEGE 75 11 MOORPARK COLLEGE 373 68 COLLEGE OF ALAMEDA 74 12 SADDLEBACK COLLEGE 350 69 COLLEGE OF THE DESERT 74 13 EAST LOS ANGELES COLLEGE 323 70 MERCED COLLEGE 71 14 GLENDALE COLLEGE 316 71 SAN BERNARDINO VALLEY COLLEGE 69 15 SAN DIEGO MESA COLLEGE 312 72 ANTELOPE VALLEY COLLEGE 68 16 LOS ANGELES PIERCE COLLEGE 308 73 CONTRA COSTA COLLEGE 68 17 RIVERSIDE COLLEGE 299 74 CLOVIS COMMUNITY COLLEGE 64 18 CITY COLLEGE OF SAN FRANCISCO 284 75 LOS ANGELES HARBOR COLLEGE 63 19 MIRACOSTA COLLEGE 284 76 MISSION COLLEGE 63 20 FULLERTON COLLEGE 263 77 ALLAN HANCOCK COLLEGE 62 21 SACRAMENTO CITY COLLEGE 253 78 CRAFTON HILLS COLLEGE 61 22 CABRILLO COLLEGE 252 79 BAKERSFIELD COLLEGE 55 23 BERKELEY CITY COLLEGE 251 80 FRESNO CITY COLLEGE 51 24 COLLEGE OF SAN MATEO 247 81 SAN JOSE CITY COLLEGE 46 25 COLLEGE OF THE CANYONS 244 82 EVERGREEN VALLEY COLLEGE 45 26 AMERICAN RIVER COLLEGE 243 83 VICTOR VALLEY COLLEGE 45 27 OHLONE COLLEGE -

California Community College Transfers by Campus to California

California Community College Transfers by Campus to California State University System Year 2009-2010 1 EL CAMINO COLLEGE 871 57 SAN DIEGO CITY COLLEGE 272 2 ORANGE COAST COLLEGE 860 58 CABRILLO COLLEGE 262 3 DE ANZA COLLEGE 843 59 SAN DIEGO MIRAMAR COLLEGE 261 4 LONG BEACH CITY COLLEGE 813 60 IRVINE VALLEY COLLEGE 259 5 PASADENA CITY COLLEGE 808 61 MERCED COLLEGE 259 6 DIABLO VALLEY COLLEGE 782 62 COLLEGE OF THE DESERT 256 7 SANTA MONICA COLLEGE 780 63 COLLEGE OF SAN MATEO 242 8 GROSSMONT COLLEGE 764 64 FOLSOM LAKE COLLEGE3 229 9 MOUNT SAN ANTINIO COLLEGE 759 65 SKYLINE COLLEGE 229 10 FULLERTON COLLEGE 756 66 HARTNELL COLLEGE 228 11 PALOMAR COLLEGE 754 67 FOOTHILL COLLEGE 227 12 BAKERSFIELD COLLEGE 746 68 ALLAN HANCOCK COLLEGE 224 13 SAN DIEGO MESA COLLEGE 727 69 SAN BERNARDINO VALLEY COLLEGE 224 14 SIERRA COLLEGE 724 70 YUBA COLLEGE 224 15 LOS ANGELES PIERCE COLLEGE 723 71 IMPERIAL VALLEY COLLEGE 223 16 MOORPARK COLLEGE 706 72 LOS ANGELES VALLEY COLLEGE 216 17 RIVERSIDE COLLEGE 649 73 SAN JOSE CITY COLLEGE 197 18 BUTTE COLLEGE 648 74 CUYAMACA COLLEGE 196 19 CITY COLLEGE OF SAN FRANCISCO 648 75 LOS MEDANOS COLLEGE 195 20 FRESNO CITY COLLEGE 644 76 VICTOR VALLEY COLLEGE 190 21 AMERICAN RIVER COLLEGE 615 77 MISSION COLLEGE 188 22 SAN JOAQUIN DELTA COLLEGE 601 78 COLLEGE OF THE REDWOODS 187 23 CERRITOS COLLEGE 594 79 LOS ANGELES MISSION COLLEGE 176 24 SANTA ROSA JUNIOR COLLEGE 581 80 CONTRA COSTA COLLEGE 175 25 SOUTHWESTERN COLLEGE 576 81 LANEY COLLEGE 170 26 SADDLEBACK COLLEGE 551 82 CRAFTON HILLS COLLEGE 163 27 MODESTO JUNIOR COLLEGE -

Spring 2019 Class Schedule

TABLE OF CONTENTS Mission, Vision and Values ...........1 Fast Track Courses ....................98 Late Start Courses ...................100 Forwarding Your Zonemail...........1 Weekend Courses.................... 101 Spring 2019 Semester Calender ......2 MISSION STATEMENT Fees and Payment Policy ......... 102 Las Positas College is an inclusive Steps to Success.....................3 learning-centered institution Financial Aid .....................104 providing educational opportunities Admission Information ..............4 and support for completion of Academic and Student Support students’ transfer, degree, basic skills, Course Registration Procedures ......6 Services .......................... 105 career-technical, and retraining goals. Stay Connected .....................7 College Policies and Procedures... 108 Enrollment Policies and Procedures ..8 Campus Safety and Security .......111 VISION STATEMENT Las Positas College strives to be Registration Dates ................. 10 Parking Permits ...................114 California’s premier Community Orientation, Assessment and Emergency Alert System...........114 College, setting the standard through Educational Plan....................11 opportunities for developing Bookstore Information.............115 knowledge, skills, values, and Degree, Certificate and Transfer abilities that foster engaged and Programs ..........................12 Transit (Bus) Pass Information ......115 contributing members of the society. Spring 2019 Courses 14-88 Campus Directory .................116 How to -

ASHC Welcomes Dr. Hsieh and Trustees to Townhall 400 Enjoy Gala

Nov. 22, 2019 Note to readers: The President’s Weekly Report will take a break for the Thanksgiving holiday and resume the following week. ASHC welcomes Dr. Hsieh and trustees to Townhall Members of the Hartnell Community College District Board of Trustees and I were delighted on Nov. 18 to participate in a Townhall Meeting organized by the Associated Students of Hartnell College (ASHC). Joined by ASHC President and Student Trustee Samantha Saldana, who helped initiate this opportunity for dialogue, we each shared information about our personal backgrounds and why we are inspired to serve Hartnell College. About 50 students attended the event in the Student Center on Main Campus, and they asked thoughtful questions about how to support and honor student diversity at Hartnell and how the college will maintain high-quality student services on its satellite campuses, including the new centers being constructed in Soledad and Castroville. ASHC Secretary Robert Cali Rendon served as moderator. I know all of the trustees who participated shared the sentiment expressed by Board President Aurelio Salazar Jr., who said at the Nov. 19 board meeting that he looked forward to another town hall session in the future. (Pictured, from left: Superintendent-President Dr. Patricia Hsieh, Vice President Pat Donohue, President Aurelio Salazar Jr., Trustee Manuel Osorio, Trustee Candi DePauw, Trustee Erica Padilla-Chavez and Student Trustee Samantha Saldana.) 400 enjoy gala in support of arts programs at Hartnell The 2019 Black & White Gala for the Arts drew a crowd of 400 people who enjoyed a reception and silent auction (pictured) in the Willard Lewallen STEM Center, followed by an exclusive performance of “Evita” by The Western Stage in the Mainstage Theater. -

UCI Honors to Honors Program

Honors to Honors Eligible students are granted early admission to UCI (not necessarily to their first choice of major) and guaranteed admission to the prestigious Campuswide Honors Collegium. Students also receive priority consideration for a special set of merit-based scholarships. How do I become eligible for Honors to Honors? • Attain a UC transferable GPA of 3.7 or higher. • Submit a UC Admissions Application to UCI no later than November 30, 2020. • You must be confirmed by your Community College Honors Program Director as a member in good standing, and must successfully complete your Honors Program requirements by the end of the spring semester prior to transfer. • After applying to UCI, you must be verified by a UCI Admissions evaluator as having completed all transfer requirements, including the prerequisites for your major. Your College Contact: _________________________________________________________________________________________ Visit admissions.uci.edu to learn more about UCI. Explore Campuswide Honors Collegium at honors.uci.edu. Honors to Honors students admitted to the Campuswide Honors Collegium are required to take an honors seminar in the first year, and to engage in mentored research that culminates in a senior honors thesis. Honors to Honors is available for high achieving students entering in fall 2021 who are currently in honors programs at one of these partner colleges: American River College Glendale Community College Orange Coast College Antelope Valley College Grossmont College Pasadena City College Cabrillo -

Analysis of the America Rescue Plan Federal Stimulus

MEMO March 12, 2021 TO: Chancellor Eloy Ortiz Oakley Chief Executive Officers Chief Business Officers Chief Student Services Officers Chief Instructional Officers FROM: Lizette Navarette, Vice Chancellor, College Finance and Facilities Planning David O’ Brien, Vice Chancellor, Government Relations RE: Analysis of the America Rescue Plan Federal Stimulus Summary On Thursday, March 11, 2021, President Joe Biden signed the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan into law. The new federal stimulus includes a robust investment in higher education with resources available for a longer period of time. Half of the resources each colleges receives will go to support direct emergency grants to students. Bill Details The new federal Coronavirus stimulus bill earmarks nearly $170 billion for education, including $39.6 billion for a third round of funding into the Higher Education Emergency Relief (HEER) Fund. The HEER III dollars will be allocated using the same methodology as the previous two iterations (with some slight modifications) and requires institutions that receive this funding to allocate at least 50% of those dollars to students in the form of emergency grants. One welcome distinction over previous stimulus bills is that the American Rescue Plan specifies funds will be available for use by institutions through September 30, 2023. Specifically, the $39 billion investment in the Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund will be distributed as follows: • 37.5 percent based on FTE Pell recipients, not exclusively enrolled in distance education courses prior to the emergency; • 37.5 percent based on headcount Pell recipients; • 11.5 percent based on overall FTE students; • 11.5 percent based on overall headcount of students; • 1 percent based on FTE Pell exclusively online recipients (may only be used for student grants); and • 1 percent based on headcount Pell exclusively online recipients (may only be used for student grants). -

November Town Meeting

NOVEMBER TOWN MEETING Welcome/Announcements William Garcia ASLPC Update Tatiana Hernandez Security Master Plan Kevin Wood Catalyst Consulting Group Unified Plan: Basic Skills Initiative, Student Equity, and Student Success and Support Programs Nessa Julian Trends in Student Characteristics and Outcomes Rajinder Samra November 1, 2017 Variable FLEX Plans Due by November 15, 2017 • Electronically submit your Variable FLEX Plans to Howard Blumenfeld using the form on the Professional Development Website (you only need to fill in Part 1). • You will be notified by email only if there are problems with your plan that need to be corrected. If you do not hear back from Howard by January, you can assume your plan is fine. 2nd Wednesdays 6 p.m. – 9 p.m. Swirl on the Square – 21 S. Livermore Avenue Bring your instrument or your voice! Free and open to the public. CHILL & CHAT Date Time Where Event 11/1 2pm-3:30pm 1620 Chill ‘n Chat 11/15 2pm-3:30pm 1620 Chill ‘n Chat 11/29 2pm-3:30pm 1620 Chill ‘n Chat 12/6 2pm-3:30pm 1620 Chill ‘n Chat 12/13 2pm-3:30pm 1620 Chill ‘n Chat 1/31 2pm-3:30pm 1620 Chill ‘n Chat CHILL & CHAT Date Time Where Event 2/7 2pm-3:30pm 1620 Chill ‘n Chat 3/21 2pm-3:30pm 1620 Chill ‘n Chat 4/18 2pm-3:30pm 1620 Chill ‘n Chat 4/25 2pm-3:30pm 1620 Chill ‘n Chat 5/2 2pm-3:30pm 1620 Chill ‘n Chat 5/23 2pm-3:30pm 1620 Chill ‘n Chat Date Time Where Event 11/8 2pm-3:30pm 1602 Exploring your identity and the role of social media on identity and body image; how to ask for help 12/13 2pm-3:30pm 1602 Increasing coping skills to survive -

Las Positas Connection

Las Positas Connection The President’s Monthly Report to the Board of Trustees, Campus, and Community | November 2018 Roanna Bennie, Las Positas College Interim President Board President LPC Honors Veterans Dr. Marshall Mitzman Attends LPC’s Veterans Day CLPCCD Board of Trustees President, Dr. Marshall Mitzman, participated in honoring Veterans on November 7 at LPC with Interim President Roanna Bennie and Veterans First Coordinator Todd Steffan. Also honored for their on- going support of LPC were SAP SR, Blue Star Moms of Danville, Pleasanton Military Families, and Rotary of Livermore—RAVE— Rotaries Assisting Veterans Education. In This Issue Veterans Honored LLNL/LPC Science Journalism Stu- & Engineering dents Science Series Men’s Basketball Public Safety Ma- Women’s Water jors Fair Polo Vocal East Dreammakers & AGS Conference Risktakers CDC Student Winners Across the College Campus Journalism Students Take 7 Awards Men’s Basketball An LPC delegation of 12 journalism students won LPC Head Coach James Giacomazzi led his Men’s seven awards at the NorCal Conference for Basketball team to victory at the Tony Costello Tip- the Journalism Association of Community Off Classic on November 3 defeating College of the Colleges held recently at the San Joaquin Delta Siskiyous 79-63, Butte College 79-62, and Contra College. The awards covered writing, design, Costa College 74-70. photography, videography and illustration. The LPC Special Recognitions students from both “Naked” magazine and “The Michael Hayes, MVP Express” competed against 200 other delegates from schools throughout Northern California. All Tournament: John Ketchel, Decaurey Brown, Alafia Oluwasogo In the category Publication Awards, the LPC students took 1st Place Photo Illustration, 2nd Place Webcast/Broadcast News, 3rd Place Editorial Cartoon, 4th Place Front Page Layout, and Honorable Mention Illustration. -

Faculty and Staff Diversity at College of Marin, the Bay Area 10, and Santa Rosa Junior College September 2015

Faculty and Staff Diversity at College of Marin, the Bay Area 10, and Santa Rosa Junior College September 2015 Introduction This research compares College of Marin (COM) to the 20 community colleges at the other 9 districts in the Bay Area (Bay-10) and Santa Rosa Junior College (SRJC). Using the Fall 2014 data from the California Community College Chancellor’s Office (CCCCO) DataMart, we looked at each college’s employee diversity and the extent to which it reflects the student population. The purpose of this research is to help inform the process of student equity planning. Recent research found improved academic performance and long-term outcomes for minority students who are taught by minority faculty. Based on this research, the Community College League of California (CCLC) has recommended that faculty members reflecting the diversity of the student population participate in the formulation and implementation of the schools’ student equity plans.1 Therefore this report is particularly concerned with noting disparities between minority student populations and faculty, though we include comparisons by college for all employees, and disaggregated by faculty, classified staff, and administration. For each major race/ethnic category, we considered differences of less than 2 percentage points between the student population and employees as equivalent. In some cases, the percentage gap is much larger than 2%. While there is no research standard for gauging the equivalence of race/ethnicity, we are setting a conservative standard of equivalence to assure that statistical differences are highlighted. In practice, in terms of whether students are likely to see themselves represented among campus employees, this may be a narrow band, but the purpose of this report is to show the differences in the data so that colleges can use it for their own planning. -

President's Message

PRESIDENTUPDATE’S APRIL 2013 IN THIS ISSUE President’s Message April has been a very busy month! I encourage you to read about all the exciting President’s Message and informative events that have been planned for our campus community, including the Spring Job and Internship Fair; the Transfer Conference, and the series of timely workshops coordinated by the ‘YOU MATTER’ Health and 50th Anniversary Wellness project. Celebration Big Hit I would like to take this opportunity to thank our volunteers who have helped us orchestrate a full year of events to celebrate the 50th Anniversary of Rio Hondo College. Our 50th Anniversary Task Force was comprised of a cross-section of Board Update campus representatives, including senior faculty, managers and confidentials, classified staff, as well as support staff and students. Together we have coordinated major events such as ‘Rio Fest’, the Time Capsule and ‘Birthday Bash’ celebration. RioSource Gets Boost from Task Force members included Susan Herney, Teresa Buell, Martha Carreon, Russell Castaneda-Calleros, Lyla Eddington, Adele Enright, Nash Flores, Mental Health Grant Karen Koos, Jasmine Lopez, Shari Magnus, Don Mason, Mike Munoz, Jim Poper, Teresa Dreyfuss Sandy Sandello, and Sylvia Viramontes. Tenure and Academic Rank Additional volunteers assisted in the planning and execution of the 50th Anniversary Celebration event April 19 at the Industry Hills Expo Center, where we presented new Medallion awards to 17 individuals who have made extraordinary contributions to Rio Hondo College through the years. Recipients who joined us Presidential Finalists and for the event included Ted Snyder, Yosh Nakamura, Jean Prinz Korf, Don L Jenkins, Patrick Boyle, Dr.