Understanding Detroit Rock Music Through Oral History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STICK MEN - Tony Levin and Pat Mastelo�O, the Powerhouse Bass and Drums of the Group King Crimson for a Few Decades, Bring That Tradi�On to All Their Playing

STICK MEN - Tony Levin and Pat Masteloo, the powerhouse bass and drums of the group King Crimson for a few decades, bring that tradion to all their playing. Levin plays the Chapman Sck, from which the band takes it’s name. Having bass and guitar strings, the Chapman Sck funcons at mes like two instruments. Markus Reuter plays his selfdesigned touch style guitar – again covering much more ground than a guitar or a bass. And Masteloo’s drumming encompasses not just the acousc kit, but a unique electronic setup too, allowing him to add loops, samples, percussion and more. TONY LEVIN - Born in Boston, Tony Levin started out in classical music, playing bass in the Rochester Philharmonic. Then moving into jazz and rock, he has had a notable career, recording and touring with John Lennon, Pink Floyd, Yes, Alice Cooper, Gary Burton, Buddy Rich and many more. He has also released 5 solo CDs and three books. In addion to touring with Sck Men, since more than 30 years is currently a member of King Crimson and Peter Gabriel Band, and jazz bands Levin Brothers and L’Image. His popular website, tonylevin.com, featured one of the web’s first blogs, and has over 4 million visits. PAT MASTELOTTO - Very rarely does a drummer go on to forge the most successful career on the demise of their former hit band. Phil Collins and Dave Grohl have managed it, so too has Pat Masteloo, a self taught drummer from Northern California, who has also been involved with pushing the envelope of electronic drumming. -

Queen of the Blues © Photos AP/Wideworld 46 D INAHJ ULY 2001W EASHINGTONNGLISH T EACHING F ORUM 03-0105 ETF 46 56 2/13/03 2:15 PM Page 47

03-0105_ETF_46_56 2/13/03 2:15 PM Page 46 J Queen of the Blues © Photos AP/WideWorld 46 D INAHJ ULY 2001W EASHINGTONNGLISH T EACHING F ORUM 03-0105_ETF_46_56 2/13/03 2:15 PM Page 47 thethe by Kent S. Markle RedRed HotHot BluesBlues AZZ MUSIC HAS OFTEN BEEN CALLED THE ONLY ART FORM J to originate in the United States, yet blues music arose right beside jazz. In fact, the two styles have many parallels. Both were created by African- Americans in the southern United States in the latter part of the 19th century and spread from there in the early decades of the 20th century; both contain the sad sounding “blue note,” which is the bending of a particular note a quar- ter or half tone; and both feature syncopation and improvisation. Blues and jazz have had huge influences on American popular music. In fact, many key elements we hear in pop, soul, rhythm and blues, and rock and roll (opposite) Dinah Washington have their beginnings in blues music. A careful study of the blues can contribute © AP/WideWorld Photos to a greater understanding of these other musical genres. Though never the Born in 1924 as Ruth Lee Jones, she took the stage name Dinah Washington and was later known leader in music sales, blues music has retained a significant presence, not only in as the “Queen of the Blues.” She began with singing gospel music concerts and festivals throughout the United States but also in our daily lives. in Chicago and was later famous for her ability to sing any style Nowadays, we can hear the sound of the blues in unexpected places, from the music with a brilliant sense of tim- ing and drama and perfect enun- warm warble of an amplified harmonica on a television commercial to the sad ciation. -

THURSDAY—( Cont'd)

B— Lowell Thomas, See Monday KFBK KFH KFPY KFRC KGB KHJ THURSDAY—( Cont'd) KLRA KLZ KMBC KMJ KMOX ED-10:30 p.m., E-9:30, C-8:30, M-7:30 ED-7:00 p.m., E-6:00, C-5:00, M-4: 0 KOIN KOL KOMA KRLD KSCJ KSL C — Doris Lorraine; Cadets C — Myrt and Marge,See Monday KTRH KTSA KVI KWG WABC KLRA KMOX KOMA KTSA WABC B— Amos'n' Andy,See Monday WADC WBBM WBRC WBT WCAO WBRC WBT WCAO WGST WHAS ED-7:15 p.m., E-6:15, C-5:15, M-4:15 WCAU WCCO WDOD WDRC WDSU WKRC WLAC WMBR WREC WRR C — Just Plain Bill, See Monday WEAN WFBL WFBM WGST WHAS B — Archer Gibson, Organist B — Billy Bachelor,See Monday WHK WIBW WICC WJAS WJSV KDKA ESO KWCR KYW WBAL WBZ WKBW WKRC WLAC WMBG WMT WBZA WCKY WGAR WHAM WJZ ED-7:30 p.m., E-6:30, C-5:30, M-4:30 WNAC WOKO WOWO WREC WSPD WMAL WREN C— Music in Air,See Monday. WTAR WTOC B — George Gershwin, See Monday B — Armour Program; Phil Baker ED-10:45 p.m., E-9:45, C-8:45,M-7:45 ED-7:45 p.m., E-6:45, C-5:45 M-4:45 KDKA KDYL KFI KGO KGW KHQ C — Fray and Braggiotti B — Gus Van; Arlene Jackson KOA KOIL KOMO KPRC KSO KSTP CKLW WAAB WABO WADC WCAO KDKA WBAL WBZ WBZA WCKY KTAR KWK WAPI WBAL WBZ WDRC WFBL WFEA WGLC WHEC WBZA WEBC WENR WFAA WGAR WJAS WJSV WLAC WLBW WLBZ WENR WJZ WMAL WMC WSB WSM WHAM WIOD WJAX WJR WJZ WOKO WOWO WSPD WSMB WSYR WKY WMC WOAI WREN WRVA C — Myrt and Marge, See Monday C — Boake Carter, See Monday WSB WSM WSMB WTMJ WWNC R— Goldbergs, See Monday R — One Night Stand; Pick and Pat ED-11:00 p.m., E-10:00, C-9:00, M-8:00 ED-8:00 p.m., E-7:00, C-6:00, 11/1-5:00 KSD WBEN WCAE WCSH WDAF B — Amos 'n' Andy, See Monday C — Happy -

JD Reynolds Is an Artist in the Truest Sense of the Word

JD Reynolds is an artist in the truest sense of the word. A true singer, a real songwriter, a neoteric producer, an incredible dancer and striking performer, all wrapped up in a stunning package that could grace the cover of any magazine in the world, and yet, her down to earth country girl charm is what makes this extraordinary artist so real. JD Reynolds was born an artist. “It’s in my blood. Music, melody, lyrics and dance flow through my veins, gifts straight from God for which I am thankful”. JD’s Mother had Elvis, Michael Jackson, Prince, Roy Orbison, Dolly Parton and Whitney Houston on daily replay in the house, so JD grew up listening to the King of Rock ‘n Roll, The Prince of Pop, The PRINCE of Everything, The Caruso of Rock, The Queen of Country Music and The Queen of the Night. JD’s sound is fresh originality for country music. “My entire album came to me like a bolt of lightning, the JD sound, my sound, respecting country music routes yet having my own next level twist”. As an up and coming producer, JD teamed up with seasoned producer Braddon Williams to co-produce what country music insiders have nicknamed “The Jagged Little Pill of country". Braddon has achieved more than thirty top-ten hits, amassed over thirty times platinum in record sales, and his work has received both Grammy and ARIA award nominations, credits include Beyoncé, Snoop Dogg, P Diddy, The Script, Kelly Clarkson, and his latest favourite, JD Reynolds. Braddon knew he was helping to create a unique country album for an incredible talent. -

Legitimizing Pay to Play: Marketizing Radio Content Through a Responsive Auction Mechanism

LEGITIMIZING PAY TO PLAY: MARKETIZING RADIO CONTENT THROUGH A RESPONSIVE AUCTION MECHANISM Alon Rotem* I. INTRODUCTION ............................................. 130 II. RADIO REGULATION BACKGROUND / HISTORY ........ 131 A. Government Enforced Public Interest Standards...... 131 B. Marketization of the Public Interest Doctrine ........ 133 C. The Impact of the 1996 Telecommunications Act on License Renewals .................................... 134 III. PAYOLA RULES ............................................ 135 A. Payola Rules Impact on the Recording Industry ...... 136 B. A Brief History of Payola Transgressions ............ 137 C. Falloutfrom Recent Payola Prosecution .............. 139 D. Modern Payola Rules Ambiguity ..................... 139 IV. IMPACT OF TECHNOLOGY AND AUCTIONS ON BROAD- CAST SCARCITY ............................................ 140 A. The Rise and Evolution of Technology-Driven A uctions ....... ..................................... 141 B. Applying the Auction Mechanism to Radio Content Programm ing ........................................ 141 * J.D. Candidate 2007, University of California, Berkeley, Boalt Hall School of Law. B.S. Managerial Economics, 2001, University of California, Davis. I would like to thank my wife, Nicole, parents, Doron and Batsheva, and brothers, Tommy and Jonathan for their love, support, and encouragement. Additionally, I would like to thank Professor Howard Shelanski for his wisdom and guidance in the "Telecommunications Law & Policy" class for which this comment was written. Special thanks to Paul Cohune, who has generously de- voted his time to editing this and virtually every paper I have written in the last 10 years, to Zach Katz for sharing his profound knowledge of the music industry, and to my future col- leagues at Ropes & Gray, LLP. I am also very grateful for the assistance of the editors of the UCLA Entertainment Law Review. Mr. Rotem welcomes comments at alon.rotem@ gmail.com. -

Global Reach. LOCAL GRASP

LEGALIFE DIAZ REUS Moscow office MIAMI LOS ANGELES NEW YORK WASHINGTON, D.C. MOSCOW CARACAS SHANGHAI DUBAI MADRID FRANKFURT LIMA BOGOTA’ MEXICO CITY BUENOS AIRES SANTO DOMINGO PANAMA SANTIAGO RIYADH SAN PEDRO SULA PRAGUE GUATEMALA SAO PAULO global reach. LOCAL GRASP. Presentation BUDDHA-BAR MIAMI Investment Offer Disclaimer Offer This presentation by LegaLife Diaz Reus LegaLife Diaz Reus law firm has an law firm is intended only for the personal international mandate to offer to a select use of the recipient(s). This presentation clientele an exclusive investment may be an attorney-client communication opportunity to acquire a majority and as such privileged and ownership of the legal entity that owns confidential. If you are not an intended the franchise rights to develop buddha- recipient, you may not review, copy or bar in Miami. distribute this presentation. If you have received this presentation by error, please notify us immediately and delete the original presentation. Investment Offer: buddha-bar Miami LEGALIFE DIAZ REUS Moscow office __The buddha-bar concept Antigua “Since its creation in 1996, Buddha-Bar Paris has been the precursor to a true 'Art of Living' concept, with confluent influences from the Pacific Rim. This restaurant-bar-lounge, located on the ultra- chic Faubourg St Honoré, was created thanks to the visionary imagination of its founder Raymond Visan, owner of the famous Barfly in Paris. On a constant quest for new ideas gathered during his numerous. trips, particularly to California, Mr. Visan launched the Buddha- Bar that rapidly became a must-see and be-seen in the French capital. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

First Steps with the Drum Set a Play Along Approach to Learning the Drums

First Steps With The Drum Set a play along approach to learning the drums JOHN SAYRE www.JohnSayreMusic.com 1 CONTENTS Page 5: Part 1, FIRST STEPS Money Beat, Four on the Floor, Four Rudiments Page 13: Part 2, 8th NOTES WITH ACCENTS Page 18: Part 3, ROCK GROOVES 8th notes, Queen, R.E.M., Stevie Wonder, Nirvana, etc. Page 22: Part 4, 16th NOTES WITH ACCENTS Page 27: Part 5, 16th NOTES ON DRUM SET Page 34: Part 6, PLAYING IN BETWEEN THE HI-HAT David Bowie, Bob Marley, James Brown, Led Zeppelin etc. Page 40: Part 7, RUDIMENTS ON THE DRUM SET Page 46: Part 8, 16th NOTE GROOVES Michael Jackson, Erykah Badu, Imagine Dragons etc. Page 57: Part 9, TRIPLETS Rudiments, Accents Page 66: Part 10, TRIPLET-BASED GROOVES Journey, Taj Mahal, Toto etc. Page 72: Part 11, UNIQUE GROOVES Grateful Dead, Phish, The Beatles etc. Page 76: Part 12, DRUMMERS TO KNOW 2 INTRODUCTION This book focuses on helping you get started playing music that has a backbeat; rock, pop, country, soul, funk, etc. If you are new to the drums I recommend working with a teacher who has a healthy amount of real world professional experience. To get the most out of this book you will need: -Drumsticks -Access to the internet -Device to play music -Good set of headphones—I like the isolation headphones made by Vic Firth -Metronome you can plug headphones into -Music stand -Basic understanding of reading rhythms—quarter, eighth, triplets, and sixteenth notes -Drum set: bass drum, snare drum, hi-hat is a great start -Other musicians to play with Look up any names, bands, and words you do not know. -

TOBY DAVID COLLECTION 1930’S – 1970’S Primarily 1935-1964

TOBY DAVID COLLECTION 1930’s – 1970’s Primarily 1935-1964 Accession Number: 2001.024 Size: 1 linear foot Number of Boxes: 2 archival boxes Box Numbers: BIO-5-D1 to BIO-5-D2 Object Numbers: 2001.024.029 to 2001.024.393 TOBY DAVID COLLECTION ACQUISITION: Donated to the Detroit Historical Museum by Gerald David in 2001. OWNERSHIP & COPYRIGHT: The Detroit Historical Society except where copyrights for publications, manuscripts, and photos remain in effect. ARRANGEMENT: Organized, researched, and cataloged with a finding aid prepared by Lauren Aquilina, Wayne State University practicum student, in January – April, 2019. ACCESS & USE: Opened to researchers and other interested individuals in 2019 without restriction except where physical condition or technology precludes use. BACKGROUND HISTORY of COLLECTION This collection contains mostly photographs as well as some papers and ephemera of Toby David during his career in radio and television spanning from 1935 to 1964. David was born in New Bern, North Carolina, on September 22, 1914, and moved to the Detroit area with his family in the mid-1920s. He attended Ford Trade School in Highland Park before getting a job at Chrysler where he performed in their amateur talent shows. His first radio job was at CKLW in Windsor, Ontario, on The Early Morning Frolic beginning in 1935. In 1940, David moved to Washington, D.C., with Larry Marino. Together, they were a comedy duo known as The Kibitzers. While in D.C. during World War II, David organized Treasury bond shows, entertained servicemen, and emceed President Roosevelt’s birthday celebrations three years in a row. -

Global Nomads: Techno and New Age As Transnational Countercultures

1111 2 Global Nomads 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1011 1 2 A uniquely ‘nomadic ethnography,’ Global Nomads is the first in-depth treat- 3111 ment of a counterculture flourishing in the global gulf stream of new electronic 4 and spiritual developments. D’Andrea’s is an insightful study of expressive indi- vidualism manifested in and through key cosmopolitan sites. This book is an 5 invaluable contribution to the anthropology/sociology of contemporary culture, 6 and presents required reading for students and scholars of new spiritualities, 7 techno-dance culture and globalization. 8 Graham St John, Research Fellow, 9 School of American Research, New Mexico 20111 1 D'Andrea breaks new ground in the scholarship on both globalization and the shaping of subjectivities. And he does so spectacularly, both through his focus 2 on neomadic cultures and a novel theorization. This is a deeply erudite book 3 and it is a lot of fun. 4 Saskia Sassen, Ralph Lewis Professor of Sociology 5 at the University of Chicago, and Centennial Visiting Professor 6 at the London School of Economics. 7 8 Global Nomads is a unique introduction to the globalization of countercultures, 9 a topic largely unknown in and outside academia. Anthony D’Andrea examines 30111 the social life of mobile expatriates who live within a global circuit of counter- 1 cultural practice in paradoxical paradises. 2 Based on nomadic fieldwork across Spain and India, the study analyzes how and why these post-metropolitan subjects reject the homeland to shape an alternative 3 lifestyle. They become artists, therapists, exotic traders and bohemian workers seek- 4 ing to integrate labor, mobility and spirituality within a cosmopolitan culture of 35 expressive individualism. -

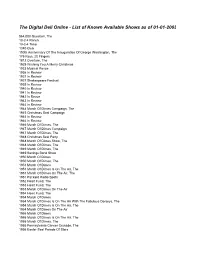

The Digital Deli Online - List of Known Available Shows As of 01-01-2003

The Digital Deli Online - List of Known Available Shows as of 01-01-2003 $64,000 Question, The 10-2-4 Ranch 10-2-4 Time 1340 Club 150th Anniversary Of The Inauguration Of George Washington, The 176 Keys, 20 Fingers 1812 Overture, The 1929 Wishing You A Merry Christmas 1933 Musical Revue 1936 In Review 1937 In Review 1937 Shakespeare Festival 1939 In Review 1940 In Review 1941 In Review 1942 In Revue 1943 In Review 1944 In Review 1944 March Of Dimes Campaign, The 1945 Christmas Seal Campaign 1945 In Review 1946 In Review 1946 March Of Dimes, The 1947 March Of Dimes Campaign 1947 March Of Dimes, The 1948 Christmas Seal Party 1948 March Of Dimes Show, The 1948 March Of Dimes, The 1949 March Of Dimes, The 1949 Savings Bond Show 1950 March Of Dimes 1950 March Of Dimes, The 1951 March Of Dimes 1951 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1951 March Of Dimes On The Air, The 1951 Packard Radio Spots 1952 Heart Fund, The 1953 Heart Fund, The 1953 March Of Dimes On The Air 1954 Heart Fund, The 1954 March Of Dimes 1954 March Of Dimes Is On The Air With The Fabulous Dorseys, The 1954 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1954 March Of Dimes On The Air 1955 March Of Dimes 1955 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1955 March Of Dimes, The 1955 Pennsylvania Cancer Crusade, The 1956 Easter Seal Parade Of Stars 1956 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1957 Heart Fund, The 1957 March Of Dimes Galaxy Of Stars, The 1957 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1957 March Of Dimes Presents The One and Only Judy, The 1958 March Of Dimes Carousel, The 1958 March Of Dimes Star Carousel, The 1959 Cancer Crusade Musical Interludes 1960 Cancer Crusade 1960: Jiminy Cricket! 1962 Cancer Crusade 1962: A TV Album 1963: A TV Album 1968: Up Against The Establishment 1969 Ford...It's The Going Thing 1969...A Record Of The Year 1973: A Television Album 1974: A Television Album 1975: The World Turned Upside Down 1976-1977. -

Nielsen Broadcast Data Systems (BDS) to Track XM Satellite Radio Airplay

NEWS RELEASE Nielsen Broadcast Data Systems (BDS) to Track XM Satellite Radio Airplay 6/24/2003 Washington D.C., June 24, 2003 -- XM Satellite Radio, the nation's leading satellite radio service, announced that Nielsen Broadcasting Data Systems (BDS) will begin tracking music played on XM Satellite Radio starting next month. Record labels depend on Nielsen BDS for information about radio airplay. As the music industry's leading music- monitoring service, Nielsen BDS provides data that Billboard magazine uses to determine its airplay charts. XM Satellite Radio is the first and only satellite radio company to be monitored by Nielsen BDS. Nielsen BDS will utilize its extensive computer technology to identify songs played on ten XM Satellite Radio channels 24 hours a day, 365 days a year throughout the United States. XM playlists, as monitored by Nielsen BDS, will be available to Nielsen BDS subscribers and included in its national airplay charts. "BDS monitoring heralds a new stage in XM's growth and importance as our commitment to breaking artists can now be fully illustrated and documented to the music community," said Lee Abrams, chief programming officer for XM Satellite Radio. "The fact that BDS wants to track the songs played on XM is a great reflection of the impact that XM is making on radio listeners." "Nielsen BDS is committed to providing meaningful information on music airplay whether from terrestrial radio or from any other significant delivery platform. XM's pioneering role in satellite radio and their overwhelming consumer acceptance makes it clear that their information will impact Nielsen BDS's services in a very positive way," said Rob Sisco, president of Nielsen Music and COO of Nielsen Retail Entertainment Information.