Cyclic Patterns of Movement Across Weaving, Epiplokē and Live Coding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

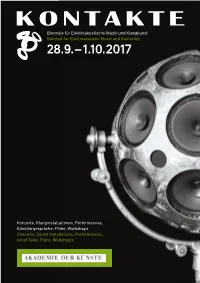

Konzerte, Klanginstallationen, Performances, Künstlergespräche, Filme, Workshops Concerts, Sound Installations, Performances, Artist Talks, Films, Workshops

Biennale für Elektroakustische Musik und Klangkunst Biennial for Electroacoustic Music and Sound Art 28.9. – 1.10.2017 Konzerte, Klanginstallationen, Performances, Künstlergespräche, Filme, Workshops Concerts, Sound Installations, Performances, Artist Talks, Films, Workshops 1 KONTAKTE’17 28.9.–1.10.2017 Biennale für Elektroakustische Musik und Klangkunst Biennial for Electroacoustic Music and Sound Art Konzerte, Klanginstallationen, Performances, Künstlergespräche, Filme, Workshops Concerts, Sound Installations, Performances, Artist Talks, Films, Workshops KONTAKTE '17 INHALT 28. September bis 1. Oktober 2017 Akademie der Künste, Berlin Programmübersicht 9 Ein Festival des Studios für Elektroakustische Musik der Akademie der Künste A festival presented by the Studio for Electro acoustic Music of the Akademie der Künste Konzerte 10 Im Zusammenarbeit mit In collaboration with Installationen 48 Deutsche Gesellschaft für Elektroakustische Musik Berliner Künstlerprogramm des DAAD Forum 58 Universität der Künste Berlin Hochschule für Musik Hanns Eisler Berlin Technische Universität Berlin Ausstellung 62 Klangzeitort Helmholtz Zentrum Berlin Workshop 64 Ensemble ascolta Musik der Jahrhunderte, Stuttgart Institut für Elektronische Musik und Akustik der Kunstuniversität Graz Laboratorio Nacional de Música Electroacústica Biografien 66 de Cuba singuhr – projekte Partner 88 Heroines of Sound Lebenshilfe Berlin Deutschlandfunk Kultur Lageplan 92 France Culture Karten, Information 94 Studio für Elektroakustische Musik der Akademie der Künste Hanseatenweg 10, 10557 Berlin Fon: +49 (0) 30 200572236 www.adk.de/sem EMail: [email protected] KONTAKTE ’17 www.adk.de/kontakte17 #kontakte17 KONTAKTE’17 Die zwei Jahre, die seit der ersten Ausgabe von KONTAKTE im Jahr 2015 vergangen sind, waren für das Studio für Elektroakustische Musik eine ereignisreiche Zeit. Mitte 2015 erhielt das Studio eine großzügige Sachspende ausgesonderter Studiotechnik der Deut schen Telekom, die nach entsprechenden Planungs und Wartungsarbeiten seit 2016 neue Produktionsmöglichkeiten eröffnet. -

French Underground Raves of the Nineties. Aesthetic Politics of Affect and Autonomy Jean-Christophe Sevin

French underground raves of the nineties. Aesthetic politics of affect and autonomy Jean-Christophe Sevin To cite this version: Jean-Christophe Sevin. French underground raves of the nineties. Aesthetic politics of affect and autonomy. Political Aesthetics: Culture, Critique and the Everyday, Arundhati Virmani, pp.71-86, 2016, 978-0-415-72884-3. halshs-01954321 HAL Id: halshs-01954321 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01954321 Submitted on 13 Dec 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. French underground raves of the 1990s. Aesthetic politics of affect and autonomy Jean-Christophe Sevin FRENCH UNDERGROUND RAVES OF THE 1990S. AESTHETIC POLITICS OF AFFECT AND AUTONOMY In Arundhati Virmani (ed.), Political Aesthetics: Culture, Critique and the Everyday, London, Routledge, 2016, p.71-86. The emergence of techno music – commonly used in France as electronic dance music – in the early 1990s is inseparable from rave parties as a form of spatiotemporal deployment. It signifies that the live diffusion via a sound system powerful enough to diffuse not only its volume but also its sound frequencies spectrum, including infrabass, is an integral part of the techno experience. In other words listening on domestic equipment is not a sufficient condition to experience this music. -

An AI Collaborator for Gamified Live Coding Music Performances

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Falmouth University Research Repository (FURR) Autopia: An AI Collaborator for Gamified Live Coding Music Performances Norah Lorway,1 Matthew Jarvis,1 Arthur Wilson,1 Edward J. Powley,2 and John Speakman2 Abstract. Live coding is \the activity of writing (parts of) regards to this dynamic between the performer and audience, a program while it runs" [20]. One significant application of where the level of risk involved in the performance is made ex- live coding is in algorithmic music, where the performer mod- plicit. However, in the context of the system proposed in this ifies the code generating the music in a live context. Utopia3 paper, we are more concerned with the effect that this has on is a software tool for collaborative live coding performances, the performer themselves. Any performer at an algorave must allowing several performers (each with their own laptop pro- be prepared to share their code publicly, which inherently en- ducing its own sound) to communicate and share code during courages a mindset of collaboration and communal learning a performance. We propose an AI bot, Autopia, which can with live coders. participate in such performances, communicating with human performers through Utopia. This form of human-AI collabo- 1.2 Collaborative live coding ration allows us to explore the implications of computational creativity from the perspective of live coding. Collaborative live coding takes its roots from laptop or- chestra/ensemble such as the Princeton Laptop Orchestra (PLOrk), an ensemble of computer based instruments formed 1 Background at Princeton University [19]. -

Spaces to Fail In: Negotiating Gender, Community and Technology in Algorave

Spaces to Fail in: Negotiating Gender, Community and Technology in Algorave Feature Article Joanne Armitage University of Leeds (UK) Abstract Algorave presents itself as a community that is open and accessible to all, yet historically, there has been a lack of diversity on both the stage and dance floor. Through women- only workshops, mentoring and other efforts at widening participation, the number of women performing at algorave events has increased. Grounded in existing research in feminist technology studies, computing education and gender and electronic music, this article unpacks how techno, social and cultural structures have gendered algorave. These ideas will be elucidated through a series of interviews with women participating in the algorave community, to centrally argue that gender significantly impacts an individual’s ability to engage and interact within the algorave community. I will also consider how live coding, as an embodied techno-social form, is represented at events and hypothesise as to how it could grow further as an inclusive and feminist practice. Keywords: gender; algorave; embodiment; performance; electronic music Joanne Armitage lectures in Digital Media at the School of Media and Communication, University of Leeds. Her work covers areas such as physical computing, digital methods and critical computing. Currently, her research focuses on coding practices, gender and embodiment. In 2017 she was awarded the British Science Association’s Daphne Oram award for digital innovation. She is a current recipient of Sound and Music’s Composer-Curator fund. Outside of academia she regularly leads community workshops in physical computing, live coding and experimental music making. Joanne is an internationally recognised live coder and contributes to projects including laptop ensemble, OFFAL and algo-pop duo ALGOBABEZ. -

Download the Conference Abstracts Here

THURSDAY 8 SEPTEMBER 2016: SESSIONS 1‐4 Maciej Fortuna and Krzysztof Dys (Academy of Music, Poznán) BIOGRAPHIES Maciej Fortuna is a Polish trumpeter, composer and music producer. He has a PhD degree in Musical Arts and an MA degree in Law and actively pursues his artistic career. In his work, he strives to create his own language of musical expression and expand the sound palette of his instrument. He enjoys experimenting with combining different art forms. An important element of his creative work consists in the use of live electronics. He creates and directs multimedia concerts and video productions. Krzysztof Dys is a Polish jazz pianist. He has a PhD degree in Musical Arts. So far he has collaborated with the great Polish vibrafonist Jerzy Milian, with famous saxophonist Mikoaj Trzaska, and as well with clarinettist Wacaw Zimpel. Dys has worked on a regular basis with young, Poznań‐based trumpeter, Maciej Fortuna. Their album Tropy has been well‐received by the audience and critics as well. Dys also plays in Maciej Fortuna Quartet, with Jakub Mielcarek, double bass, and Przemysaw Jarosz, drums. In 2013 the group toured outside Poland with a project ‘Jazz from Poland’, with a goal to present the work of unappreciated or forgotten or Polish jazz composers. The main inspiration for Krzysztof Dys is the work of Russian composers Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin, Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev, American artists like Bill Evans and Miles Davis, and last but not least, a great Polish composer, Grayna Bacewicz. TITLE Classical Inspirations in Jazz Compositions Based on Selected Works by Roman Maciejewski ABSTRACT A few years prior to commencing a PhD programme, I started my own research on the possibilities of implementing electronic sound modifiers into my jazz repertoire. -

Neotrance and the Psychedelic Festival DC

Neotrance and the Psychedelic Festival GRAHAM ST JOHN UNIVERSITY OF REGINA, UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND Abstract !is article explores the religio-spiritual characteristics of psytrance (psychedelic trance), attending speci"cally to the characteristics of what I call neotrance apparent within the contemporary trance event, the countercultural inheritance of the “tribal” psytrance festival, and the dramatizing of participants’ “ultimate concerns” within the festival framework. An exploration of the psychedelic festival offers insights on ecstatic (self- transcendent), performative (self-expressive) and re!exive (conscious alternative) trajectories within psytrance music culture. I address this dynamic with reference to Portugal’s Boom Festival. Keywords psytrance, neotrance, psychedelic festival, trance states, religion, new spirituality, liminality, neotribe Figure 1: Main Floor, Boom Festival 2008, Portugal – Photo by jakob kolar www.jacomedia.net As electronic dance music cultures (EDMCs) flourish in the global present, their relig- ious and/or spiritual character have become common subjects of exploration for scholars of religion, music and culture.1 This article addresses the religio-spiritual Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 1(1) 2009, 35-64 + Dancecult ISSN 1947-5403 ©2009 Dancecult http://www.dancecult.net/ DC Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture – DOI 10.12801/1947-5403.2009.01.01.03 + D DC –C 36 Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture • vol 1 no 1 characteristics of psytrance (psychedelic trance), attending specifically to the charac- teristics of the contemporary trance event which I call neotrance, the countercultural inheritance of the “tribal” psytrance festival, and the dramatizing of participants’ “ul- timate concerns” within the framework of the “visionary” music festival. -

James Russell Lowell - Poems

Classic Poetry Series James Russell Lowell - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive James Russell Lowell(22 February 1819 – 12 August 1891) James Russell Lowell was an American Romantic poet, critic, editor, and diplomat. He is associated with the Fireside Poets, a group of New England writers who were among the first American poets who rivaled the popularity of British poets. These poets usually used conventional forms and meters in their poetry, making them suitable for families entertaining at their fireside. Lowell graduated from Harvard College in 1838, despite his reputation as a troublemaker, and went on to earn a law degree from Harvard Law School. He published his first collection of poetry in 1841 and married Maria White in 1844. He and his wife had several children, though only one survived past childhood. The couple soon became involved in the movement to abolish slavery, with Lowell using poetry to express his anti-slavery views and taking a job in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania as the editor of an abolitionist newspaper. After moving back to Cambridge, Lowell was one of the founders of a journal called The Pioneer, which lasted only three issues. He gained notoriety in 1848 with the publication of A Fable for Critics, a book-length poem satirizing contemporary critics and poets. The same year, he published The Biglow Papers, which increased his fame. He would publish several other poetry collections and essay collections throughout his literary career. Maria White died in 1853, and Lowell accepted a professorship of languages at Harvard in 1854. -

James Russell Lowell Among My Books

JAMES RUSSELL LOWELL AMONG MY BOOKS 2008 – All rights reserved Non commercial use permitted AMONG MY BOOKS First Series by JAMES RUSSELL LOWELL * * * * * To F.D.L. Love comes and goes with music in his feet, And tunes young pulses to his roundelays; Love brings thee this: will it persuade thee, Sweet, That he turns proser when he comes and stays? * * * * * CONTENTS. DRYDEN WITCHCRAFT SHAKESPEARE ONCE MORE NEW ENGLAND TWO CENTURIES AGO LESSING ROUSSEAU AND THE SENTIMENTALISTS * * * * * DRYDEN.[1] Benvenuto Cellini tells us that when, in his boyhood, he saw a salamander come out of the fire, his grandfather forthwith gave him a sound beating, that he might the better remember so unique a prodigy. Though perhaps in this case the rod had another application than the autobiographer chooses to disclose, and was intended to fix in the pupil's mind a lesson of veracity rather than of science, the testimony to its mnemonic virtue remains. Nay, so universally was it once believed that the senses, and through them the faculties of observation and retention, were quickened by an irritation of the cuticle, that in France it was customary to whip the children annually at the boundaries of the parish, lest the true place of them might ever be lost through neglect of so inexpensive a mordant for the memory. From this practice the older school of critics would seem to have taken a hint for keeping fixed the limits of good taste, and what was somewhat vaguely called _classical_ English. To mark these limits in poetry, they set up as Hermae the images they had made to them of Dryden, of Pope, and later of Goldsmith. -

Salt Lake City August 1—4, 2019 Nfac Discover 18 Ad OL.Pdf 1 6/13/19 8:29 PM

47th Annual National Flute Association Convention Salt Lake City August 1 —4, 2019 NFAc_Discover_18_Ad_OL.pdf 1 6/13/19 8:29 PM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Custom Handmade Since 1888 Booth 110 wmshaynes.com Dr. Rachel Haug Root Katie Lowry Bianca Najera An expert for every f lutist. Three amazing utists, all passionate about helping you und your best sound. The Schmitt Music Flute Gallery offers expert consultations, easy trials, and free shipping to utists of all abilities, all around the world! Visit us at NFA booth #126! Meet our specialists, get on-site ute repairs, enter to win prizes, and more. schmittmusic.com/f lutegallery Wiseman Flute Cases Compact. Strong. Comfortable. Stylish. And Guaranteed for life. All Wiseman cases are hand- crafted in England from the Visit us at finest materials. booth 214 in All instrument combinations the exhibit hall, supplied – choose from a range of lining colours. Now also NFA 2019, Salt available in Carbon Fibre. Lake City! Dr. Rachel Haug Root Katie Lowry Bianca Najera An expert for every f lutist. Three amazing utists, all passionate about helping you und your best sound. The Schmitt Music Flute Gallery offers expert consultations, easy trials, and free shipping to utists of all abilities, all around the world! Visit us at NFA booth #126! Meet our specialists, get on-site ute repairs, enter to win prizes, and more. 00 44 (0)20 8778 0752 [email protected] schmittmusic.com/f lutegallery www.wisemanlondon.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the President ................................................................... 11 Officers, Directors, Staff, Convention Volunteers, and Competition Committees ............................................................... -

Marvel in the Midwest

But Madison was hardly an early- music.” Bowles is amazed by how the serve as artists who also lead workshops music mecca, and, indeed, most residents event has been able to build a stand- for everyone from beginners to pre- probably didn’t know anything about out profile in a city flush with festivals professionals. It’s a formula the Rowes the specialized field. Put simply, it was of all kinds. “The community has instituted at the beginning and have a big risk. The couple moved ahead really, really embraced this festival,” continued all along. “If that were to anyway, recruiting Chelcy Bowles, who she said. change very much,” Bowles said, taught in the University of Wisconsin’s The summer event established “it wouldn’t be the same festival.” Division of Continuing Education, as itself as one of this country’s most It also doesn’t hurt that the festival a co-founder and the festival’s program important early-music festivals by takes place at the University of director (essentially executive director). differentiating itself right from the start. Wisconsin-Madison in partnership And the threesome’s initiative has clearly Not only is it situated away from the with its Mead Witter School of paid off. From July 6-13, the Madison two coasts, where similar offerings Music. The university provides both Early Music Festival will mark its are mostly found, but it also focuses 20th-anniversary season. mainly on medieval and Renaissance “It went fast,” Bensman-Rowe said, music and not the more prominent “and it’s a happy surprise that it’s been Baroque era. -

International Computer Music Conference (ICMC/SMC)

Conference Program 40th International Computer Music Conference joint with the 11th Sound and Music Computing conference Music Technology Meets Philosophy: From digital echos to virtual ethos ICMC | SMC |2014 14-20 September 2014, Athens, Greece ICMC|SMC|2014 14-20 September 2014, Athens, Greece Programme of the ICMC | SMC | 2014 Conference 40th International Computer Music Conference joint with the 11th Sound and Music Computing conference Editor: Kostas Moschos PuBlished By: x The National anD KapoDistrian University of Athens Music Department anD Department of Informatics & Telecommunications Panepistimioupolis, Ilissia, GR-15784, Athens, Greece x The Institute for Research on Music & Acoustics http://www.iema.gr/ ADrianou 105, GR-10558, Athens, Greece IEMA ISBN: 978-960-7313-25-6 UOA ISBN: 978-960-466-133-6 Ξ^ĞƉƚĞŵďĞƌϮϬϭϰʹ All copyrights reserved 2 ICMC|SMC|2014 14-20 September 2014, Athens, Greece Contents Contents ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 Sponsors ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 Preface ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 Summer School ....................................................................................................................................... -

Boom Festival | Rehearsing the Future

Boom festival | Rehearsing the Future Music and the Prefiguration of Change by Saul Roosendaal 5930057 Master’s thesis Musicology August 2016 supervised by dr. Barbara Titus University of Amsterdam Boom festival | Rehearsing the future Contents Foreword .................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 1. A Transformational Festival ................................................................................................. 9 1.1 Psytrance and Celebration ........................................................................................... 9 1.2 Music and Culture ..................................................................................................... 12 1.3 Dance and Musical Embodiment .............................................................................. 15 1.4 Art, Aesthetics and Spirituality ................................................................................. 18 1.5 Summary ................................................................................................................... 21 2. Music and Power: Prefigurating Change ........................................................................... 23 2.1 Education: The Liminal Village as Forum ................................................................ 25 2.1.1 Drugs and Policies .........................................................................................