A 5 3 6 Music. a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of San Francisco State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Booker Little

1 The TRUMPET of BOOKER LITTLE Solographer: Jan Evensmo Last update: Feb. 11, 2020 2 Born: Memphis, April 2, 1938 Died: NYC. Oct. 5, 1961 Introduction: You may not believe this, but the vintage Oslo Jazz Circle, firmly founded on the swinging thirties, was very interested in the modern trends represented by Eric Dolphy and through him, was introduced to the magnificent trumpet playing by the young Booker Little. Even those sceptical in the beginning gave in and agreed that here was something very special. History: Born into a musical family and played clarinet for a few months before taking up the trumpet at the age of 12; he took part in jam sessions with Phineas Newborn while still in his teens. Graduated from Manassas High School. While attending the Chicago Conservatory (1956-58) he played with Johnny Griffin and Walter Perkins’s group MJT+3; he then played with Max Roach (June 1958 to February 1959), worked as a freelancer in New York with, among others, Mal Waldron, and from February 1960 worked again with Roach. With Eric Dolphy he took part in the recording of John Coltrane’s album “Africa Brass” (1961) and led a quintet at the Five Spot in New York in July 1961. Booker Little’s playing was characterized by an open, gentle tone, a breathy attack on individual notes, a nd a subtle vibrato. His soli had the brisk tempi, wide range, and clean lines of hard bop, but he also enlarged his musical vocabulary by making sophisticated use of dissonance, which, especially in his collaborations with Dolphy, brought his playing close to free jazz. -

Victory and Sorrow: the Music & Life of Booker Little

ii VICTORY AND SORROW: THE MUSIC & LIFE OF BOOKER LITTLE by DYLAN LAGAMMA A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History & Research written under the direction of Henry Martin and approved by _________________________ _________________________ Newark, New Jersey October 2017 i ©2017 Dylan LaGamma ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION VICTORY AND SORROW: THE MUSICAL LIFE OF BOOKER LITTLE BY DYLAN LAGAMMA Dissertation Director: Henry Martin Booker Little, a masterful trumpeter and composer, passed away in 1961 at the age of twenty-three. Little's untimely death, and still yet extensive recording career,1 presents yet another example of early passing among innovative and influential trumpeters. Like Clifford Brown before him, Theodore “Fats” Navarro before him, Little's death left a gap the in jazz world as both a sophisticated technician and an inspiring composer. However, unlike his predecessors Little is hardly – if ever – mentioned in jazz texts and classrooms. His influence is all but non-existent except to those who have researched his work. More than likely he is the victim of too early a death: Brown passed away at twenty-five and Navarro, twenty-six. Bob Cranshaw, who is present on Little's first recording,2 remarks, “Nobody got a chance to really experience [him]...very few remember him because nobody got a chance to really hear him or see him.”3 Given this, and his later work with more avant-garde and dissonant harmonic/melodic structure as a writing partner with Eric Dolphy, it is no wonder that his remembered career has followed more the path of James P. -

Where to Study Jazz 2019

STUDENT MUSIC GUIDE Where To Study Jazz 2019 JAZZ MEETS CUTTING- EDGE TECHNOLOGY 5 SUPERB SCHOOLS IN SMALLER CITIES NEW ERA AT THE NEW SCHOOL IN NYC NYO JAZZ SPOTLIGHTS YOUNG TALENT Plus: Detailed Listings for 250 Schools! OCTOBER 2018 DOWNBEAT 71 There are numerous jazz ensembles, including a big band, at the University of Central Florida in Orlando. (Photo: Tony Firriolo) Cool perspective: The musicians in NYO Jazz enjoyed the view from onstage at Carnegie Hall. TODD ROSENBERG FIND YOUR FIT FEATURES f you want to pursue a career in jazz, this about programs you might want to check out. 74 THE NEW SCHOOL Iguide is the next step in your journey. Our As you begin researching jazz studies pro- The NYC institution continues to evolve annual Student Music Guide provides essen- grams, keep in mind that the goal is to find one 102 NYO JAZZ tial information on the world of jazz education. that fits your individual needs. Be sure to visit the Youthful ambassadors for jazz At the heart of the guide are detailed listings websites of schools that interest you. We’ve com- of jazz programs at 250 schools. Our listings are piled the most recent information we could gath- 120 FIVE GEMS organized by region, including an International er at press time, but some information might have Excellent jazz programs located in small or medium-size towns section. Throughout the listings, you’ll notice changed, so contact a school representative to get that some schools’ names have a colored banner. detailed, up-to-date information on admissions, 148 HIGH-TECH ED Those schools have placed advertisements in this enrollment, scholarships and campus life. -

Mesia Austin, Percussion Received Much of the Recognition Due a Venerable Jazz Icon

and Blo win' The Blues Away (1959), which includes his famous, "Sister Sadie." He also combined jazz with a sassy take on pop through the 1961 hit, "Filthy McNasty." As social and cultural upheavals shook the nation during the late 1960s and early 1970s, Silver responded to these changes through music. He commented directly on the new scene through a trio of records called United States of Mind (1970-1972) that featured the spirited vocals of Andy Bey. The composer got deeper into cosmic philosophy as his group, Silver 'N Strings, recorded Silver 'N Strings School of Music Play The Music of the Spheres (1979). After Silver's long tenure with Blue Note ended, he continued to presents create vital music. The 1985 album, Continuity of Spirit (Silveto), features his unique orchestral collaborations. In the 1990s, Silver directly answered the urban popular music that had been largely built from his influence on It's Got To Be Funky (Columbia, 1993). On Jazz Has A Sense of Humor (Verve, 1998), he shows his younger SENIOR RECITAL group of sidemen the true meaning of the music. Now living surrounded by a devoted family in California, Silver has Mesia Austin, percussion received much of the recognition due a venerable jazz icon. In 2005, the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences (NARAS) gave him its President's Merit Award. Silver is also anxious to tell the Theresa Stephens, clarinet Brian Palat, percussion world his life story in his own words as he just released his autobiography, Let's Get To The Nitty Gritty. -

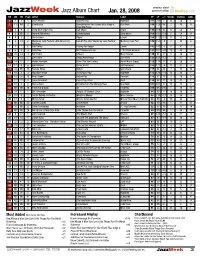

Jazzweek Jazz Album Chart Jan

airplay data JazzWeek Jazz Album Chart Jan. 28, 2008 powered by TW LW 2W Peak Artist Release Label TP LP +/- Weeks Stations Adds 1 1 1 1 Steve Nelson Sound-Effect HighNote 211 210 1 13 56 1 2 11 NR 2 Eliane Elias Something For You: Eliane Elias Sings & Blue Note 196 128 68 2 49 14 Plays Bill Evans 3 5 9 2 Deep Blue Organ Trio Folk Music Origin 194 169 25 15 52 1 4 2 NR 2 Hendrik Meurkens Sambatropolis Zoho Music 166 185 -19 2 54 13 5 4 2 2 Jim Snidero Tippin’ Savant 154 172 -18 11 53 1 6 6 33 6 Monterey Jazz Festival 50th Aniversary Live At The 2007 Monterey Jazz Festival Monterey Jazz Fest 145 154 -9 3 43 8 All-Stars 7 7 7 6 Bob DeVos Playing For Keeps Savant 142 145 -3 11 47 0 8 3 5 3 Andy Bey Ain’t Necessarily So 12th Street Records 137 182 -45 10 49 0 9 20 34 9 Ron Blake Shayari Mack Avenue 136 94 42 3 46 11 10 7 14 7 Joe Locke Sticks And Strings Jazz Eyes 132 145 -13 7 37 5 11 14 11 2 Herbie Hancock River: The Joni Letters Verve Music Group 125 114 11 17 50 0 12 12 8 8 John Brown Terms Of Art Self Released 123 127 -4 11 32 0 13 28 NR 13 Pamela Hines Return Spice Rack 117 84 33 2 43 14 14 10 3 3 Houston Person Thinking Of You HighNote 115 139 -24 13 38 2 15 18 38 15 Brad Goode Nature Boy Delmark 112 97 15 3 29 6 16 22 21 3 Cyrus Chestnut Cyrus Plays Elvis Koch 110 93 17 16 37 1 17 16 6 6 Stacey Kent Breakfast On The Morning Tram Blue Note 101 101 0 16 33 0 18 NR NR 18 Frank Kimbrough Air Palmetto 100 NR 100 1 36 31 19 24 11 1 Eric Alexander Temple Of Olympic Zeus HighNote 94 90 4 18 39 0 20 15 4 2 Gerald Wilson Orchestra Monterey -

Wavelength (December 1981)

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 12-1981 Wavelength (December 1981) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (December 1981) 14 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/14 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ML I .~jq Lc. Coli. Easy Christmas Shopping Send a year's worth of New Orleans music. to your friends. Send $10 for each subscription to Wavelength, P.O. Box 15667, New Orleans, LA 10115 ·--------------------------------------------------r-----------------------------------------------------· Name ___ Name Address Address City, State, Zip ___ City, State, Zip ---- Gift From Gift From ISSUE NO. 14 • DECEMBER 1981 SONYA JBL "I'm not sure, but I'm almost positive, that all music came from New Orleans. " meets West to bring you the Ernie K-Doe, 1979 East best in high-fideUty reproduction. Features What's Old? What's New ..... 12 Vinyl Junkie . ............... 13 Inflation In Music Business ..... 14 Reggae .............. .. ...... 15 New New Orleans Releases ..... 17 Jed Palmer .................. 2 3 A Night At Jed's ............. 25 Mr. Google Eyes . ............. 26 Toots . ..................... 35 AFO ....................... 37 Wavelength Band Guide . ...... 39 Columns Letters ............. ....... .. 7 Top20 ....................... 9 December ................ ... 11 Books ...................... 47 Rare Record ........... ...... 48 Jazz ....... .... ............. 49 Reviews ..................... 51 Classifieds ................... 61 Last Page ................... 62 Cover illustration by Skip Bolen. Publlsller, Patrick Berry. Editor, Connie Atkinson. -

Discography of the Mainstream Label

Discography of the Mainstream Label Mainstream was founded in 1964 by Bob Shad, and in its early history reissued material from Commodore Records and Time Records in addition to some new jazz material. The label released Big Brother & the Holding Company's first material in 1967, as well as The Amboy Dukes' first albums, whose guitarist, Ted Nugent, would become a successful solo artist in the 1970s. Shad died in 1985, and his daughter, Tamara Shad, licensed its back catalogue for reissues. In 1991 it was resurrected in order to reissue much of its holdings on compact disc, and in 1993, it was purchased by Sony subsidiary Legacy Records. 56000/6000 Series 56000 mono, S 6000 stereo - The Commodore Recordings 1939, 1944 - Billy Holiday [1964] Strange Fruit/She’s Funny That Way/Fine and Mellow/Embraceable You/I’ll Get By//Lover Come Back to Me/I Cover the Waterfront/Yesterdays/I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues/I’ll Be Seeing You 56001 mono, S 6001 stereo - Begin the Beguine - Eddie Heywood [1964] Begin the Beguine/Downtown Cafe Boogie/I Can't Believe That You're in Love with Me/Carry Me Back to Old Virginny/Uptown Cafe Boogie/Love Me Or Leave Me/Lover Man/Save Your Sorrow 56002 mono, S 6002 stereo - Influence of Five - Hawkins, Young & Others [1964] Smack/My Ideal/Indiana/These Foolish Things/Memories Of You/I Got Rhythm/Way Down Yonder In New Orleans/Stardust/Sittin' In/Just A Riff 56003 mono, S 6003 stereo - Dixieland-New Orleans - Teagarden, Davison & Others [1964] That’s A- Plenty/Panama/Ugly Chile/Riverboat Shuffle/Royal Garden Blues/Clarinet -

May • June 2013 Jazz Issue 348

may • june 2013 jazz Issue 348 &blues report now in our 39th year May • June 2013 • Issue 348 Lineup Announced for the 56th Annual Editor & Founder Bill Wahl Monterey Jazz Festival, September 20-22 Headliners Include Diana Krall, Wayne Shorter, Bobby McFerrin, Bob James Layout & Design Bill Wahl & David Sanborn, George Benson, Dave Holland’s PRISM, Orquesta Buena Operations Jim Martin Vista Social Club, Joe Lovano & Dave Douglas: Sound Prints; Clayton- Hamilton Jazz Orchestra, Gregory Porter, and Many More Pilar Martin Contributors Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, Dewey Monterey, CA - Monterey Jazz Forward, Nancy Ann Lee, Peanuts, Festival has announced the star- Wanda Simpson, Mark Smith, Duane studded line up for its 56th annual Verh, Emily Wahl and Ron Wein- Monterey Jazz Festival to be held stock. September 20–22 at the Monterey Fairgrounds. Arena and Grounds Check out our constantly updated Package Tickets go on sale on to the website. Now you can search for general public on May 21. Single Day CD Reviews by artists, titles, record tickets will go on sale July 8. labels, keyword or JBR Writers. 15 2013’s GRAMMY Award-winning years of reviews are up and we’ll be lineup includes Arena headliners going all the way back to 1974. Diana Krall; Wayne Shorter Quartet; Bobby McFerrin; Bob James & Da- Comments...billwahl@ jazz-blues.com vid Sanborn featuring Steve Gadd Web www.jazz-blues.com & James Genus; Dave Holland’s Copyright © 2013 Jazz & Blues Report PRISM featuring Kevin Eubanks, Craig Taborn & Eric Harland; Joe No portion of this publication may be re- Lovano & Dave Douglas Quintet: Wayne Shorter produced without written permission from Sound Prints; George Benson; The the publisher. -

Johnny O'neal

OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BOBDOROUGH from bebop to schoolhouse VOCALS ISSUE JOHNNY JEN RUTH BETTY O’NEAL SHYU PRICE ROCHÉ Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JOHNNY O’NEAL 6 by alex henderson [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JEN SHYU 7 by suzanne lorge General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : BOB DOROUGH 8 by marilyn lester Advertising: [email protected] Encore : ruth price by andy vélez Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : betty rochÉ 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : southport by alex henderson US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Festival Report Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, 13 Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, special feature 14 by andrey henkin Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, CD ReviewS 16 Suzanne Lorge, Mark Keresman, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, Miscellany 41 John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Event Calendar Contributing Writers 42 Brian Charette, Ori Dagan, George Kanzler, Jim Motavalli “Think before you speak.” It’s something we teach to our children early on, a most basic lesson for living in a society. -

PASIC 2010 Program

201 PASIC November 10–13 • Indianapolis, IN PROGRAM PAS President’s Welcome 4 Special Thanks 6 Area Map and Restaurant Guide 8 Convention Center Map 10 Exhibitors by Name 12 Exhibit Hall Map 13 Exhibitors by Category 14 Exhibitor Company Descriptions 18 Artist Sponsors 34 Wednesday, November 10 Schedule of Events 42 Thursday, November 11 Schedule of Events 44 Friday, November 12 Schedule of Events 48 Saturday, November 13 Schedule of Events 52 Artists and Clinicians Bios 56 History of the Percussive Arts Society 90 PAS 2010 Awards 94 PASIC 2010 Advertisers 96 PAS President’s Welcome elcome 2010). On Friday (November 12, 2010) at Ten Drum Art Percussion Group from Wback to 1 P.M., Richard Cooke will lead a presen- Taiwan. This short presentation cer- Indianapolis tation on the acquisition and restora- emony provides us with an opportu- and our 35th tion of “Old Granddad,” Lou Harrison’s nity to honor and appreciate the hard Percussive unique gamelan that will include a short working people in our Society. Arts Society performance of this remarkable instru- This year’s PAS Hall of Fame recipi- International ment now on display in the plaza. Then, ents, Stanley Leonard, Walter Rosen- Convention! on Saturday (November 13, 2010) at berger and Jack DeJohnette will be We can now 1 P.M., PAS Historian James Strain will inducted on Friday evening at our Hall call Indy our home as we have dig into the PAS instrument collection of Fame Celebration. How exciting to settled nicely into our museum, office and showcase several rare and special add these great musicians to our very and convention space. -

Biography-George-ROBERT.Pdf

George ROBERT Born on September 15, 1960 in Chambésy (Geneva), Switzerland, George Robert is internationally reCognized as one of the leading alto saxophonists in jazz today. He started piano at a very early age and at age 10 he began Clarinet lessons at the Geneva Conservatory with LuC Hoffmann. In 1980 he moved to Boston and studied alto saxophone with Joe Viola at the Berklee College of MusiC. In 1984 he earned a Bachelor of Arts in Jazz Composition & Arranging and moved to New York where he enrolled at the Manhattan SChool of MusiC. He studied with Bob Mintzer and earned a Master’s Degree in Jazz PerformanCe in 1987. He played lead alto in the Manhattan SChool of MusiC Big Band for 2 years, whiCh earned in 1985 the 1st Prize in the College Big Band Category in the Down Beat Magazine Jazz Awards In July 1984 he performed on the main stage of the Montreux Jazz Festival and earned an Outstanding PerformanCe Award from Down Beat Magazine. In 1985 & 1986 he toured Europe extensively. In 1987 he met Tom Harrell and together they founded the George Robert-Tom Harrell Quintet (with Dado Moroni, Reggie Johnson & Bill Goodwin). The group Completed 125 ConCerts worldwide between 1987 & 1992, and reCorded 5 albums. He remained in New York City and free-lanCed for 7 years, playing with Billy Hart, Buster Williams, the Lionel Hampton Big Band, the Toshiko Akiyoshi-Lew Tabackin Jazz OrChestra, Joe Lovano, and many others. He met Clark Terry and started touring with him extensively, Completing a 16- week, 65-ConCert world tour in 1991. -

Vocal Jazz in the Choral Classroom: a Pedagogical Study

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Dissertations Student Research 5-2019 Vocal Jazz in the Choral Classroom: A Pedagogical Study Lara Marie Moline Follow this and additional works at: https://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Moline, Lara Marie, "Vocal Jazz in the Choral Classroom: A Pedagogical Study" (2019). Dissertations. 576. https://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations/576 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © 2019 LARA MARIE MOLINE ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School VOCAL JAZZ IN THE CHORAL CLASSROOM: A PEDAGOGICAL STUDY A DIssertatIon SubMItted In PartIal FulfIllment Of the RequIrements for the Degree of Doctor of Arts Lara Marie MolIne College of Visual and Performing Arts School of Music May 2019 ThIs DIssertatIon by: Lara Marie MolIne EntItled: Vocal Jazz in the Choral Classroom: A Pedagogical Study has been approved as meetIng the requIrement for the Degree of Doctor of Arts in College of VIsual and Performing Arts In School of Music, Program of Choral ConductIng Accepted by the Doctoral CoMMIttee _________________________________________________ Galen Darrough D.M.A., ChaIr _________________________________________________ Jill Burgett D.A., CoMMIttee Member _________________________________________________ Michael Oravitz Ph.D., CoMMIttee Member _________________________________________________ Michael Welsh Ph.D., Faculty RepresentatIve Date of DIssertatIon Defense________________________________________ Accepted by the Graduate School ________________________________________________________ LInda L. Black, Ed.D. Associate Provost and Dean Graduate School and InternatIonal AdMIssions Research and Sponsored Projects ABSTRACT MolIne, Lara Marie.