The Golden Butterfly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CS Lewis Library

C.S. Lewis Library Background Information The majority of the Lewis Library was acquired from Wroxton College in 1986, where it had been in use by the patrons of the college library. Other titles have been given by C.S. Lewis’s friends and associates to the Wade Center. Related Materials 1. The Lewis Library Inserts Archive contains items that were found between the pages of the books in C.S. Lewis' personal library. A list and photocopies of some of the handwritten annotations in the books are also included. 2. “C.S. Lewis: A Living Library” by Margaret Anne Rogers is a thesis written about the Lewis library collection while it was at Wroxton College. 3. From the Library of C.S. Lewis: Selections from Writers who Influenced his Spiritual Journey, edited by James Bell, is an anthology of excerpts from books in Lewis’s library. Key: SIGNED: An * indicates that the book contains a signature, many by C.S. Lewis. Other names in this column indicate that the book is signed by others, e.g. W -- Warren H. Lewis, A -- Albert J. Lewis. Many books in Lewis’s library were presentation copies. UNDR: An * indicates that there is underlining in the book. ANT.: An * indicates that the book has been annotated. Bolded text: Indicates the book is shelved by title This listing is owned by the Wade Center and is not to be duplicated or deposited in another institution without written permission from the Wade Center. It is a working draft and complete accuracy is not guaranteed. Marion E. -

Wiki Guide PDF L.A

Wiki Guide PDF L.A. Noire Basic Tips General Tips 5 Essential Tips from Team Bondi Walkthrough Patrol Desk Upon Reflection Armed and Dangerous Warrants Outstanding Buyer Beware Traffic Desk The Driver's Seat A Marriage Made in Heaven The Fallen Idol Homicide Desk The Red Lipstick Murder The Golden Butterfly The Silk Stocking Murder The White Shoe Slaying The Studio Secretary Murder The Quarter Moon Murders Vice Desk The Black Caesar The Set Up Manifest Destiny Arson Desk The Gas Man A Walk in Elysian Fields House of Sticks A Polite Invitation A Different Kind of War DLC Cases A Slip of The Tongue Nicholson Electroplating Reefer Madness The Naked City The Consul's Car Outfits Newspapers Golden Film Reels Golden Film Reel Locations Street Crimes Traffic Homicide Vice Arson Hidden Vehicles Cadillac Series 75 Town Car Chrysler Woody Cisitalia Coupe Cord 810 Softtop Davis Deluxe Delahaye 135MS Cabriolet Duesenberg Walker Coupe Voisin C7 Landmarks Achievements / Trophies Asphalt Jungle Public Menace Lead Foot Miles on the Clock Stab-Rite Frequently Asked Questions Things to Know about L.A. Noire L.A. Noire Staff Credits Nudity in L.A. Noire Basic Tips Overview L.A. Noire is unlike any Rockstar game you've come to know and love. You control Cole Phelps, a war veteran trying to make a name for himself and rise in the ranks of the police hierarchy. He's sort of a straight arrow and a paragon of justice who doesn't shy away from exposing the truth through rational thinking and cold hard evidence. While there's a vast virtual 1940s Los Angeles to explore, the game is structured entirely around a blend of sometimes exciting and sometimes less glamorous detective work, which includes finding clues, apprehending suspects and interrogating witnesses. -

Reginald De Koven Collection11.Mwalb02120

Reginald De Koven collection11.MWalB02120 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 30, 2021. eng Describing Archives: A Content Standard Brandeis University 415 South St. Waltham, MA URL: https://findingaids.brandeis.edu/ Reginald De Koven collection11.MWalB02120 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Contents ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 4 Other Descriptive Information ....................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 5 - Page 2 - Reginald De Koven collection11.MWalB02120 Summary Information Repository: Brandeis University Creator: De Koven, Reginald, 1859-1920 Title: Reginald De Koven collection ID: 11.MWalB02120 Date [inclusive]: 1861-1920 Date [bulk]: 1861-1920 Physical Description: 18.00 Linear Feet Physical Description: 35 manuscript boxes -

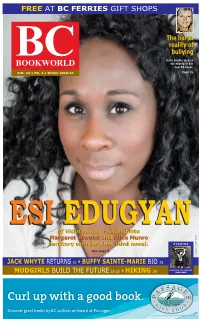

Esi Edugyan's

FREE AT BC FERRIES GIFT SHOPS TheThe harshharsh realityreality ofof BC bullying bullying Holly Dobbie tackles BOOKWORLD the misery in her new YA novel. VOL. 32 • NO. 4 • Winter 2018-19 PAGE 35 ESIESI EDUGYANEDUGYAN ofof VictoriaVictoria hashas rocketedrocketed intointo MargaretMargaret AtwoodAtwood andand AliceAlice MunroMunro PHOTO territoryterritory withwith justjust herher thirdthird novel.novel. STAMINA POPPITT See page 9 TAMARA JACK WHYTE RETURNS 10 • BUFFY SAINTE-MARIE BIO 25 PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT BUILD THE FUTURE 22-23 • 26 MUDGIRLS HIKING #40010086 Curl up with a good book. Discover great books by BC authors on board at Passages. Orca Book Publishers strives to produce books that illuminate the experiences of all people. Our goal is to provide reading material that represents the diversity of human experience to readers of all ages. We aim to help young readers see themselves refl ected in the books they read. We are mindful of this in our selection of books and the authors that we work with. Providing young people with exposure to diversity through reading creates a more compassionate world. The World Around Us series 9781459820913 • $19.95 HC 9781459816176 • $19.95 HC 9781459820944 • $19.95 HC 9781459817845 • $19.95 HC “ambitious and heartfelt.” —kirkus reviews The World Around Us Series.com The World Around Us 2 BC BOOKWORLD WINTER 2018-2019 AROUNDBC TOPSELLERS* BCHelen Wilkes The Aging of Aquarius: Igniting Passion and Purpose as an Elder (New Society $17.99) Christine Stewart Treaty 6 Deixis (Talonbooks $18.95) Joshua -

Newsletter 06/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 06/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 203 - März 2007 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 06/07 (Nr. 203) März 2007 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, spielsweise den von uns in einer vori- liebe Filmfreunde! gen Ausgabe angesprochenen BUBBA Wir gehen zum Es ist vollbracht! In einer harten HO-TEP. So, aber jetzt räumen wir WIDESCREEN Nachtschicht ist es uns gelungen, Aus- das Feld um noch rechtzeitig unsere WEEKEND gabe 203 unseres Newsletters noch Koffer zu packen und Ihnen genügend rechtzeitig vor unserer Abreise nach Gelegenheit zu geben, sich durch die nach Bradford! Bradford unter Dach und Fach zu brin- Massen von amerikanischen Releases gen. Und wie bereits angekündigt ent- zu wühlen. Übrigens gelten für alle hält diese Ausgabe nur die amerikani- Vorankündigungen selbstverständlich Daher bleibt unser schen Releases, die für die nächsten wieder unsere Pre-Order-Preise, sofern Geschäft in der Zeit vom Wochen angekündigt sind. Wer also uns Ihre Bestellung spätestens eine 15. März 2007 nur an deutscher DVD-Kost interes- Woche vor dem amerikanischen Erst- siert ist, der darf diesen Newsletter verkaufstag vorliegt. Noch Fragen? Ab bis einschließlich getrost beiseite legen. Es sei denn, Sie dem 22. März sind wir wieder in ge- 21. März 2007 möchten jetzt schon wissen, was wir wohnter Weise für Sie da. zukünftig als deutsche Veröffentlichun- geschlossen. gen erwarten dürfen. Denn die Erfah- Ihr LASER HOTLINE Team rung lehrt uns, dass die Amerikaner Wir bitten um Beachtung meist nur ein paar Wochen früher mit den Titeln auf den Markt stürmen als und danken für Ihr die europäischen Vermarkter. -

Guide to the Donald J. Stubblebine Collection of Theater and Motion Picture Music and Ephemera

Guide to the Donald J. Stubblebine Collection of Theater and Motion Picture Music and Ephemera NMAH.AC.1211 Franklin A. Robinson, Jr. 2019 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Stage Musicals and Vaudeville, 1866-2007, undated............................... 4 Series 2: Motion Pictures, 1912-2007, undated................................................... 327 Series 3: Television, 1933-2003, undated............................................................ 783 Series 4: Big Bands and Radio, 1925-1998, -

THE PITTSBURGH CATHOLIC Founded in IS Uh by Rev

IBI «8 tat THE PITTSBURGH CATHOLIC Founded in IS Uh by Rev. Michael O'Connor, First Bishop of Pittsburgh Diocese |3rd Year PITTSBURGH, MAY 27, 1926 No. 21 MRS. MOLAMPHEY IS CARDINAL, 25 THE "OLD LOG CHURCH" U. S. Makes Effort To RE-ELECTED HEAD OF THE P. C. C. W. YEARS BISHOP, Aid Vatican Delegate nwg GIVEN HONORS marts Catholic Womens' Convention Expelled By Mexico Denounces Mexican Consti- (By N. C. W. C. News Service) tution and Formally Protests Boston, May 26.—With the warm (By N. C. W. C. Now.' Service) there is danger of the policy of com- Outrages Against Catholics; felicitations and affectionate greet- promise resulting in serious danger Washington..«,„..„, May 26.—The Rev. Pledges $10,000 to School ing of the Holy Father, Cardinal O'- to the religious themselves, since un- John J. Burke, C.S.P., general secre- 1 Connell, Archbishop of Boston, yes- der such conditions "the human tary of the National Catholic Wel- Mrs. Theresa M. Molamphy, of terday celebrated his twenty-fifth heart and mind, even that of a re- ByRèbel fare Conference, today made public Pittsburgh, was unanimously re- year as a bishop of the Catholic ligious, is invaded by a sort of weak- a letter he received from Secretary elected president of the Pittsburgh Church, amid the loving acclaim of ness and temporizing which borders of State Kellogg, revealing the ac- Council of Catholic Women last the people of his archdiocese of on actual apostasy," and because tivities of the State Department in Thursday afternoon during the clos- every station in life. -

English Literature UGC NET Complete Notes Pdf.Pdf

Comprehensive Notes for UGC – NET in English Language & Literature English Literature before the Norman Conquest 500-1066 Beowulf Author: Anonymous Hero: Beowulf, King of Geats, Son of Ecgtheow Monster: Grendel King: Hrothgar, King of Danes Dialect: West Saxon 3182 lines Concludes with funeral ceremony of Beowulf. First major poem in a European vernacular. Seamus Heaney-translation-1999 Widsith The oldest poem in the language. The title of the poem means a Wide Wanderer. It is the wanderings of a minstrel or travelling singer or musician. He speaks of the feudal audience and sings of the various wars. 150 lines The Complaint of Deor Deor also is a minstrel, but he is not a wanderer. The poem is lyrical in form, with a definite refrain and may be called the first English lyric. 42 lines- 7 unequal sections. Ending with a Christian consolation. Vercelli Book An Old English Manuscript Contains: prose sermons and 3500 lines of Old English poetry. The Dream of the Rood, Andreas, Elene and The Fate of the Apostles Exeter Book One of the most important manuscripts containing Old English poetry Given by Bishop Leeofric (1072) to Exeter Cathedral Shorter Poems: The Wanderer, The Seafarer, The Wife’s Lament, The Husband’s Message, Resignation, The Complaint of Deor, Widsith, The Ruin, Wulf and Eadwacer, Longer poems: Guthlac, Christ,The Phoenix, Juliana Jithin John, Nithin Varghese Page 1 Comprehensive Notes for UGC – NET in English Language & Literature Caedmon The first native maker of English verse. An inmate of St. Hilda’s Monastery, near Whitby. An angel appeared to him in a dream and asked him to sing in praise of God. -

OTHER PRESS Random House Adult Green, Spring 2015 Omni Other

OTHER PRESS Random House Adult Green, Spring 2015 Omni Other Press A Brief Stop On the Road From Auschwitz Summary: This shattering memoir by a journalist about Goran Rosenberg, Sara Death his father’s attempt to survive the aftermath of 9781590516072 Auschwitz in a small industrial town in Sweden won the Pub Date: 2/24/15, On Sale Date: 2/24 prestigious August Prize $24.95/$28.95 Can. On August 2, 1947 a young man gets off a train in a small 352 pages Swedish town to begin his life anew. Having endured the Hardcover ghetto of Lodz, the death camp at AuschwitzBirkenau, the Biography & Autobiography / Personal Memoirs slave camps and transports during the final months of Nazi Ctn Qty: 12 Germany, his final challenge is to survive the survival. 5.500 in W | 8.250 in H | 1.250 lb Wt 140mm W | 210mm H | 567g Wt In this intelligent and deeply... Contributor Bio: Göran Rosenberg was born in 1948 in Sweden, where he is a wellknown author. In 1970 he left academia to work as a journalist for Swedish television, radio, and print. He is the author of several books, including the highly acclaimed Det Förlorade landet [The Lost Land: A Personal History of Zionism, Messianism, and the State of Israel]. Random House Adult Green, Spring 2015 Omni Other Press Blood Brothers Summary: Originally published in 1932 and banned by Ernst Haffner, Michael Hofmann the Nazis one year later, Blood Brothers follows a gang 9781590517048 of young boys bound together by unwritten rules and Pub Date: 3/3/15, On Sale Date: 3/3 mutual loyalty. -

PDF Van Tekst

Mededelingen van het Cyriel Buysse Genootschap 11 bron Mededelingen van het Cyriel Buysse Genootschap 11. Cyriel Buysse Genootschap, Gent 1995 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_med006199501_01/colofon.php © 2014 dbnl 5 Inleiding In de vorige aflevering van de Mededelingen konden we zowel in de Inleiding als in de Kroniek al aankondigen dat de zoektocht naar Buysses medewerking aan het Nederlandse maandblad Dierenbescherming een onbekend verhaaltje, ‘Tray’, had opgeleverd. Deze zoektocht werd inmiddels uitgebreid en met succes bekroond. Het lag immers voor de hand het spoor te volgen van de werkzaamheden van Cyriel Buysses zus Alice, die zoals bekend zeer actief was in tal van liefdadige instellingen en ook zeer lang voorzitster is geweest van de Koninklijke Maatschappij tot Bescherming der Dieren te Gent. Dat deze vereniging een eigen tijdschrift heeft uitgegeven was bekend; het bleek alleen niet zo eenvoudig om een exemplaar ervan te pakken te krijgen. De opdracht werd toevertrouwd aan Sibylle de Borchgrave als onderwerp van haar licentieverhandeling (Universiteit Gent, 1995). Haar speurwerk heeft alle verwachtingen overtroffen: het leverde niet alleen twee verhalen op van Cyriel Buysse zelf (waaronder trouwens ook het ontroerende ‘Tray’) maar bracht ook aan het licht dat zus Alice de leden van de Vereniging regelmatig toesprak met tal van mededelingen en bovendien ook vergastte op korte verhaaltjes in het Nederlands en in het Frans. Deze tot dusver onbekend gebleven teksten van Alice en Cyriel Buysse worden hierna integraal opgenomen, voorafgegaan door een toelichting van Sibylle de Borchgrave. In deze elfde aflevering van de Mededelingen vindt de lezer vervolgens de voortzetting van de publikatie van de jaarlijkse Kroniek over de Vlaamse literatuur die door Emile de Laveleye en Paul Fredericq werd verzorgd voor het Engelse maandblad Athenaeum. -

Download the 35Th Fajr International Film Festival Catalogue

264 In the Name of God Download PDF version of FIFF Festival Catalogue Signs Asian premiere A.P. International premiere Int.p. National premiere N.P. How to use the app World premiere W.P. get.winkere.com Regional premiere R.P. Middle East premiere ME.P Question & Answer Q&A 3 2 1 Original Voice OV Director Of Photography DOP Catalogue of 35th Fajr International Film Festival Tehran, 21st-28th. April. 2017 Supervisor: Kayvan Kassirian Editor-in-chief: Somayeh Alipour With Special Thanks to Amir Esfandiari, Iraj Taghipour, Kamyar Mohs- enin, Ali Eftekhari, Raha Pourghassem English to Persian Translator: Lida Sadrololamayi, Hafez Rouhani, Farzad Mozafari, Ghodratollah Shafiee Persian to English Translator: Ghanbar Naderi, Ahmad Khouzani, Hos- sein Bouye Editor: Masoumeh Alipour Art Manager: Hamidreza Baydaghi Graphics: Afshin Ziaeeian Alipour, Leili Eskandarpour Print Supervisor: Mehrdad Haji Hassani Printing: Senobar The Official apps of FIFF Message of Head of Iranian Cinema Organization 4 Message of the Festival Director 5 About 34th Fajr Film Festival 7 Rules and Regulations of 35th Fajr Festival 11 Juries 15 International Competition 27 Panorama of Films from Asian and Islamic Countries 73 Festival of Festivals 119 Docs in Focus 135 Special Screenings 149 Classics Preserved 177 Korean Cinema 189 Baltic Cinema 197 Shadows of Horror 205 Broken Olive Trees 213 Enviromental Films 225 Interfaith Competition Nominees 227 Here is the Friend’s Home 229 Workshops 239 Organization 255 Index 261 Message of Head Iranian Cinema Organization Deputy Minister of Culture and Islamic Guidance and Head of Iranian Cinema Organization 4 Mohammad Mehdi Heydarian has sent the followin message to the organizers of this year’s Fajr International Film Festival. -

AUTOBIOGRAPHY of SIR WALTER BESANT

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES i Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/autobiographyofsOObesa AUTOBIOGRAPHY of SIR WALTER BESANT WITH A PREFATORY NOTE BY S. SQUIRE SPRIGGE NEW YORK- DODD, MEAD AND COMPANY • MDCCCCII COPYRIGHT, 1902, BY DODD, MEAD AND CO. First Edition Published April, 1902 UNIVERSITY PRESS • JOHN WILSON AND SON • CAMBRIDGE, U. S. A. Contents CHAPTER I Child and Boy i CHAPTER II Child and Boy {continued) 33 CHAPTER III School-Boy 55 CHAPTER IV King's College, London 67 CHAPTER V Christ's College, Cambridge 79 CHAPTER VI A Tramp Abroad 102 CHAPTER VII L'Ile de France m CHAPTER VIII England again : The Palestine Exploration Fund i45 V 891981 CONTENTS CHAPTER IX PAGE First Steps in the Literary Career — and Later i68 CHAPTER X The Start in Fiction : Critics and Criti- casters 1 80 CHAPTER XI The Novelist with a Free Hand .... 198 CHAPTER XII The Society of Authors and Other Societies 215 CHAPTER XIII Philanthropic Work 243 CHAPTER XIV The Survey of London « 261 CHAPTER XV The Atlantic Union 265 CHAPTER XVI Conclusion : The Conduct of Life and the Influence of Religion 273 INDEX 287 VI — A Prefatory Note . " It is hard to speak of him within measure when we consider his devotion to the cause of authors, and the constant good service ren- dered hy him to their material interests. In this he was a valorous, alert, persistent advocate, and it will not be denied by his opponents that he was always urbane, his object being simply to establish a sys- tem of fair dealing between the sagacious publishers of books and the inexperienced, often heedless, producers.