AUTOBIOGRAPHY of SIR WALTER BESANT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Language and Conflict in English Literature from Gaskell to Tressell

ARTICULATING CLASS: LANGUAGE AND CONFLICT IN ENGLISH LITERATURE FROM GASKELL TO TRESSELL Timothy John James University of Cape Town Thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN JANUARY 1992 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town ABSTRACT ARTICULATING CLASS: LANGUAGE AND CONFLICT IN ENGLISH LITERATURE, FROM GASKELL TO TRESSELL Concentrating on English literary texts written between the 1830s and 1914 and which have the working class as their central focus, the thesis examines various ways in which class conflict inheres within the textual language, particularly as far as the representation of working-class speech is concerned. The study is made largely within V. N. Voloshinov's understanding of language. Chapter 1 examines the social role of "standard English" (including accent) and its relationship to forms of English stigmatised as inadequate, and argues that the phoneticisation of working-class speech in novels like those of William Pett Ridge is to indicate its inadequacy within a situation where use of the "standard language" is regarded as a mark of all kinds of superiority, and where the language of narrative prose has, essentially, the "accent" of "standard English". The periodisation of the thesis is discussed: the "industrial reformist" novels of the Chartist years and the "slum literature" of the 1880s and '90s were bourgeois responses to working-class struggle. -

CS Lewis Library

C.S. Lewis Library Background Information The majority of the Lewis Library was acquired from Wroxton College in 1986, where it had been in use by the patrons of the college library. Other titles have been given by C.S. Lewis’s friends and associates to the Wade Center. Related Materials 1. The Lewis Library Inserts Archive contains items that were found between the pages of the books in C.S. Lewis' personal library. A list and photocopies of some of the handwritten annotations in the books are also included. 2. “C.S. Lewis: A Living Library” by Margaret Anne Rogers is a thesis written about the Lewis library collection while it was at Wroxton College. 3. From the Library of C.S. Lewis: Selections from Writers who Influenced his Spiritual Journey, edited by James Bell, is an anthology of excerpts from books in Lewis’s library. Key: SIGNED: An * indicates that the book contains a signature, many by C.S. Lewis. Other names in this column indicate that the book is signed by others, e.g. W -- Warren H. Lewis, A -- Albert J. Lewis. Many books in Lewis’s library were presentation copies. UNDR: An * indicates that there is underlining in the book. ANT.: An * indicates that the book has been annotated. Bolded text: Indicates the book is shelved by title This listing is owned by the Wade Center and is not to be duplicated or deposited in another institution without written permission from the Wade Center. It is a working draft and complete accuracy is not guaranteed. Marion E. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Dorothy Forster: a Novel by Walter Besant 2 New From$27.95

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Dorothy Forster: a novel by Walter Besant 2 New from$27.95. Paperback$31.75. 6 New from$31.75. Title:Dorothy Forster. A novel. Publisher:British Library, Historical Print EditionsThe British Library is the national library of the United Kingdom. It is one of the world's largest research libraries holding over 150 million items in all known languages and formats: books, journals, newspapers, sound recordings, patents, maps, stamps, …4.2/5(2)Format: PaperbackAuthor: Walter BesantDorothy Forster: A Novel, Volume 1...: Besant, Walter ...https://www.amazon.com/Dorothy-Forster-Novel-Walter- Besant/dp/1279022167Besant Walter Dorothy Forster: A Novel, Volume 1... Paperback – March 29, 2012 by Walter Besant (Author)Author: Walter BesantFormat: PaperbackImages of Dorothy Forster A Novel by Walter Besant bing.com/imagesSee allSee all imagesDorothy Forster. a Novel.: Besant, Walter: 9781241480479 ...https://www.amazon.com/Dorothy-Forster-Novel-Walter-Besant/dp/1241480478Dorothy Forster. a Novel. [Besant, Walter] on Amazon.com. *FREE* shipping on qualifying offers. Dorothy Forster. a Novel. Feb 10, 2009 · Dorothy Forster: A Novel Paperback – February 10, 2009 by Walter Besant (Author) 4.2 out of 5 stars 2 ratings. See all formats and editions Hide other formats and editions. Price New from Used from Kindle "Please retry" $7.95 — — Hardcover "Please retry" $27.95 . … Reviews: 2Author: Walter BesantDorothy Forster (Volume 3); A Novel by Walter Besanthttps://www.goodreads.com/book/show/10404819...Told in the first person of Dorothy Forster, it is the story of the northern English Jacobites and the ill-fated rebellion of 1715, in which they attempted to restore James III …3.8/5Ratings: 4Reviews: 2Pages: 100Dorothy Foster by Walter Besant - Goodreadshttps://www.goodreads.com/book/show/10368482-dorothy-fosterIt was ever a distinction between the Forsters of. -

Serializing Fiction in the Victorian Press This Page Intentionally Left Blank Serializing Fiction in the Victorian Press

Serializing Fiction in the Victorian Press This page intentionally left blank Serializing Fiction in the Victorian Press Graham Law Waseda University Tokyo © Graham Law 2000 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2000 978-0-333-76019-2 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1P 0LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2000 by PALGRAVE Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N. Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world PALGRAVE is the new global academic imprint of St. Martin’s Press LLC Scholarly and Reference Division and Palgrave Publishers Ltd (formerly Macmillan Press Ltd). Outside North America ISBN 978-1-349-41360-7 ISBN 978-0-230-28674-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/9780230286740 In North America ISBN 978-0-312-23574-1 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. -

Wiki Guide PDF L.A

Wiki Guide PDF L.A. Noire Basic Tips General Tips 5 Essential Tips from Team Bondi Walkthrough Patrol Desk Upon Reflection Armed and Dangerous Warrants Outstanding Buyer Beware Traffic Desk The Driver's Seat A Marriage Made in Heaven The Fallen Idol Homicide Desk The Red Lipstick Murder The Golden Butterfly The Silk Stocking Murder The White Shoe Slaying The Studio Secretary Murder The Quarter Moon Murders Vice Desk The Black Caesar The Set Up Manifest Destiny Arson Desk The Gas Man A Walk in Elysian Fields House of Sticks A Polite Invitation A Different Kind of War DLC Cases A Slip of The Tongue Nicholson Electroplating Reefer Madness The Naked City The Consul's Car Outfits Newspapers Golden Film Reels Golden Film Reel Locations Street Crimes Traffic Homicide Vice Arson Hidden Vehicles Cadillac Series 75 Town Car Chrysler Woody Cisitalia Coupe Cord 810 Softtop Davis Deluxe Delahaye 135MS Cabriolet Duesenberg Walker Coupe Voisin C7 Landmarks Achievements / Trophies Asphalt Jungle Public Menace Lead Foot Miles on the Clock Stab-Rite Frequently Asked Questions Things to Know about L.A. Noire L.A. Noire Staff Credits Nudity in L.A. Noire Basic Tips Overview L.A. Noire is unlike any Rockstar game you've come to know and love. You control Cole Phelps, a war veteran trying to make a name for himself and rise in the ranks of the police hierarchy. He's sort of a straight arrow and a paragon of justice who doesn't shy away from exposing the truth through rational thinking and cold hard evidence. While there's a vast virtual 1940s Los Angeles to explore, the game is structured entirely around a blend of sometimes exciting and sometimes less glamorous detective work, which includes finding clues, apprehending suspects and interrogating witnesses. -

Reginald De Koven Collection11.Mwalb02120

Reginald De Koven collection11.MWalB02120 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 30, 2021. eng Describing Archives: A Content Standard Brandeis University 415 South St. Waltham, MA URL: https://findingaids.brandeis.edu/ Reginald De Koven collection11.MWalB02120 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Contents ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 4 Other Descriptive Information ....................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 5 - Page 2 - Reginald De Koven collection11.MWalB02120 Summary Information Repository: Brandeis University Creator: De Koven, Reginald, 1859-1920 Title: Reginald De Koven collection ID: 11.MWalB02120 Date [inclusive]: 1861-1920 Date [bulk]: 1861-1920 Physical Description: 18.00 Linear Feet Physical Description: 35 manuscript boxes -

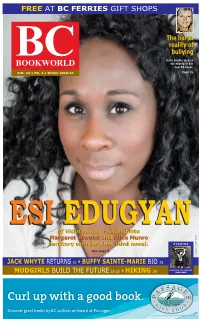

Esi Edugyan's

FREE AT BC FERRIES GIFT SHOPS TheThe harshharsh realityreality ofof BC bullying bullying Holly Dobbie tackles BOOKWORLD the misery in her new YA novel. VOL. 32 • NO. 4 • Winter 2018-19 PAGE 35 ESIESI EDUGYANEDUGYAN ofof VictoriaVictoria hashas rocketedrocketed intointo MargaretMargaret AtwoodAtwood andand AliceAlice MunroMunro PHOTO territoryterritory withwith justjust herher thirdthird novel.novel. STAMINA POPPITT See page 9 TAMARA JACK WHYTE RETURNS 10 • BUFFY SAINTE-MARIE BIO 25 PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT BUILD THE FUTURE 22-23 • 26 MUDGIRLS HIKING #40010086 Curl up with a good book. Discover great books by BC authors on board at Passages. Orca Book Publishers strives to produce books that illuminate the experiences of all people. Our goal is to provide reading material that represents the diversity of human experience to readers of all ages. We aim to help young readers see themselves refl ected in the books they read. We are mindful of this in our selection of books and the authors that we work with. Providing young people with exposure to diversity through reading creates a more compassionate world. The World Around Us series 9781459820913 • $19.95 HC 9781459816176 • $19.95 HC 9781459820944 • $19.95 HC 9781459817845 • $19.95 HC “ambitious and heartfelt.” —kirkus reviews The World Around Us Series.com The World Around Us 2 BC BOOKWORLD WINTER 2018-2019 AROUNDBC TOPSELLERS* BCHelen Wilkes The Aging of Aquarius: Igniting Passion and Purpose as an Elder (New Society $17.99) Christine Stewart Treaty 6 Deixis (Talonbooks $18.95) Joshua -

The Revolt of Man Online

8IrpS [Free] The Revolt of Man Online [8IrpS.ebook] The Revolt of Man Pdf Free Walter Besant *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #14957456 in Books Walter Besant 2013-05-05Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 9.00 x .36 x 6.00l, .48 #File Name: 1484894391142 pagesThe Revolt of Man | File size: 53.Mb Walter Besant : The Revolt of Man before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Revolt of Man: 3 of 3 people found the following review helpful. The story of `men' who live under the yolk of women in the futureBy John Drake"It is because the natural order has been reversed; the sex which should command and create is compelled to work in blind obedience."Thus is the story of `men' who live under the yolk of women in the future. This is an interesting book as it shows us a future where women rule, there is a new religion, the monarchy is abolished, and there are many good things. However, men, those pesky people want to rule. They want the old monarchy back (good god why?), and revolt against the ruling women.That's the story, and while I've told you the plot, it's the descriptions of life in this utopian or dystopian future world that make this book twice as good as the interesting plot. Written over 100 years ago, it's hard to believe, as its very much something that we could read today or see as a film and find much to discuss and think about. -

Reconsidering the Unknown Public

DRAFT Chapter One Reconsidering the Unknown Public A Puzzle of Literary Gains Simon Frost [1.0] In 1858, in an article of the same name for Household Words, Wilkie Collins discovered an “Unknown Public.” The literary preferences of this unknown public—poor, in his estimation—were a mystery to him, but he credited those readers with an emancipatory curiosity and predicted they would en- lighten themselves along a path beginning, he suggested, with Scott’s Kenil- worth and ending with the “very best men among living English writers”: including, by implication, Wilkie Collins. 1 A later solution to the puzzle of who this unknown public might be, suggested by Thomas Wright in 1883 for The Nineteenth Century,2 would have come as a surprise to Collins, but not so surprising as the implication I hope to draw out in this chapter. Collins shared the idea of a hierarchy of literatures that persists today, in which reading ought naturally to gravitate toward the “best” literature. From this perspective, any attempt to understand the experience of the poorest litera- ture would seem as perverse as any active resistance to best. From this perspective, the reading habits of the unknown public might just as well remain unknown. But from another perspective, the puzzle opens up to a different way of understanding literature, from the “poorest” to the “best.” Collins’s failure to guess the true identity of the unknown public was not simply a literary or a cultural-political one, enmeshed as he was in specific structures of literary cultural capital, but it was also a failure of method; of failing to realize that literature, for many readers, can stray beyond the liter- ary and into areas of personal gain where, perhaps worryingly for literary scholars at least, the discourse best placed to articulate those gains is eco- nomics. -

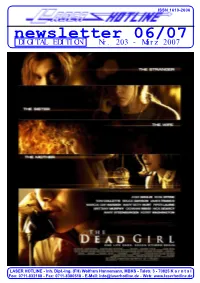

Newsletter 06/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 06/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 203 - März 2007 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 06/07 (Nr. 203) März 2007 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, spielsweise den von uns in einer vori- liebe Filmfreunde! gen Ausgabe angesprochenen BUBBA Wir gehen zum Es ist vollbracht! In einer harten HO-TEP. So, aber jetzt räumen wir WIDESCREEN Nachtschicht ist es uns gelungen, Aus- das Feld um noch rechtzeitig unsere WEEKEND gabe 203 unseres Newsletters noch Koffer zu packen und Ihnen genügend rechtzeitig vor unserer Abreise nach Gelegenheit zu geben, sich durch die nach Bradford! Bradford unter Dach und Fach zu brin- Massen von amerikanischen Releases gen. Und wie bereits angekündigt ent- zu wühlen. Übrigens gelten für alle hält diese Ausgabe nur die amerikani- Vorankündigungen selbstverständlich Daher bleibt unser schen Releases, die für die nächsten wieder unsere Pre-Order-Preise, sofern Geschäft in der Zeit vom Wochen angekündigt sind. Wer also uns Ihre Bestellung spätestens eine 15. März 2007 nur an deutscher DVD-Kost interes- Woche vor dem amerikanischen Erst- siert ist, der darf diesen Newsletter verkaufstag vorliegt. Noch Fragen? Ab bis einschließlich getrost beiseite legen. Es sei denn, Sie dem 22. März sind wir wieder in ge- 21. März 2007 möchten jetzt schon wissen, was wir wohnter Weise für Sie da. zukünftig als deutsche Veröffentlichun- geschlossen. gen erwarten dürfen. Denn die Erfah- Ihr LASER HOTLINE Team rung lehrt uns, dass die Amerikaner Wir bitten um Beachtung meist nur ein paar Wochen früher mit den Titeln auf den Markt stürmen als und danken für Ihr die europäischen Vermarkter. -

Guide to the Donald J. Stubblebine Collection of Theater and Motion Picture Music and Ephemera

Guide to the Donald J. Stubblebine Collection of Theater and Motion Picture Music and Ephemera NMAH.AC.1211 Franklin A. Robinson, Jr. 2019 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Stage Musicals and Vaudeville, 1866-2007, undated............................... 4 Series 2: Motion Pictures, 1912-2007, undated................................................... 327 Series 3: Television, 1933-2003, undated............................................................ 783 Series 4: Big Bands and Radio, 1925-1998, -

The Dissolution of the Author in Literary Collaboration

The Dissolution of the Author in Literary Collaboration: Two Case Studies by Annachiara Cozzi Literary collaboration is a mode of textual production in which two or more people are involved in all the stages of the writing of a text, and co-sign the final product. A well- established practice for the writing of opera librettos, and the theatre in general, collaboration in fiction cannot boast an equally rich tradition. However, coauthorship in novel writing knew a period, though relatively short-lived and now largely unknown of, when it constituted a prolific and fashionable literary practice. Collaboration in the writing of fiction had been practised sporadically since the eighteenth century, 1 but only in the late nineteenth century it witnessed an unprecedented expansion, probably as the result of an increasingly composite and competitive literary market which spurred “a proliferation of authors of all abilities and types” (Jamison 2016: 5). A 1 An early example of coauthorship for the writing of fiction is Memoirs of Martinus Scriblerus , the malicious satire on intellectual pretensions co-written by Alexander Pope, Jonathan Swift, John Gay, Thomas Parnell and John Arbuthnot, and published in 1741 as a part of Alexander Pope's Works . Saggi/Ensayos/Essais/Essays N. 19 – 05/2018 12 variety of literary alliances sprang up within the United Kingdom, but the phenomenon interested also the United States – so much that Ashton calls the last thirty years of the nineteenth century in the US “The Collaborative Age” (2003: 1). Starting from Dickens’s collaboration with Wilkie Collins in 1867, the subsequent decades saw the publication of a large number of coauthored novels, with a peak around the year 1890.