Orders of Merit? Hierarchy, Distinction and the British Honours System, 1917-2004

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The London Gazette, 25 March, 1930. 1895

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 25 MARCH, 1930. 1895 panion of Our Distinguished Service Order, on Sir Jeremiah Colman, Baronet, Alfred Heath- whom we have conferred the Decoration of the cote Copeman, Herbert Thomas Crosby, John Military Cross, Albert Charles Gladstone, Francis Greenwood, Esquires, Lancelot Wilkin- Alexander Shaw (commonly called the Honour- son Dent, Esquire, Officer of Our Most Excel- able Alexander Shaw), Esquires, Sir John lent Order of the British Empire, Edwin Gordon Nairne, Baronet, Charles Joeelyn Hanson Freshfield, Esquire, Sir James Hambro, Esquire, Sir Josiah Charles Stamp, Fortescue Flannery, Baronet, Charles John Knight Grand Cross of Our Most Excellent Ritchie, Esquire, Officer of Our Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, Sir Ernest Mus- Order of the British Empire; OUR right trusty grave Harvey, Knight Commander of Our and well-beloved Charles, Lord Ritchie of Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, Dundee; OUR trusty and well-beloved Sir Sir Basil Phillott Blackett, Knight Commander Alfred James Reynolds, Knight, Percy Her- of Our Most Honourable Order of the Bath, bert Pound, George William Henderson, Gwyn Knight Commander of Our Most Exalted Order Vaughan Morgan, Esquires, Frank Henry of the Star of India, Sir Andrew Rae Duncan, Cook, Esquire, Companion of Our Most Knight, Edward Robert Peacock, James Lionel Eminent Order of the Indian Empire, Ridpath, Esquires, Sir Homewood Crawford, Frederick Henry Keeling Durlacher, Esquire, Knight, Commander of Our Royal Victorian Colonel Sir Charles Elton Longmore, Knight Order; Sir William Jameson 'Soulsby, Knight Commander of Our Most Honourable Order of Commander of Our Royal Victorian Order, the Bath, Colonel Charles St. -

Chivalry in Western Literature Richard N

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses 2012 The nbU ought Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature Richard N. Boggs Rollins College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, European History Commons, Medieval History Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Boggs, Richard N., "The nbouU ght Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature" (2012). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 21. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/21 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Unbought Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies by Richard N. Boggs May, 2012 Mentor: Dr. Thomas Cook Reader: Dr. Gail Sinclair Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Master of Liberal Studies Program Winter Park, Florida The Unbought Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature By Richard N. Boggs May, 2012 Project Approved: ________________________________________ Mentor ________________________________________ Reader ________________________________________ Director, Master of Liberal Studies Program ________________________________________ Dean, Hamilton Holt School Rollins College Dedicated to my wife Elizabeth for her love, her patience and her unceasing support. CONTENTS I. Introduction 1 II. Greek Pre-Chivalry 5 III. Roman Pre-Chivalry 11 IV. The Rise of Christian Chivalry 18 V. The Age of Chivalry 26 VI. -

1 the Crown and Honours

The Crown and Honours: Getting it Right Christopher McCreery I N T R O D U C T I O N In the words of that early scholar of Commonwealth autonomy, Sir Arthur Berridale Keith, “The Crown is the fount of all honour.”i The role of the Crown as the fount of all official honours in Canada is a precept that is as old and constant as is the place of the Crown in our constitutional structure. Since the days of King Louis XIV residents of Canada have been honoured by the Crown for their services with a variety of orders, decorations and medals. The position of the Crown in the modern Canadian honours system is something that is firmly entrenched, despite consistent attempts to marginalize it in recent years. Indeed honours are not something separate from the Crown, they are an integral element of the Crown. A part that affords individuals with official recognition for what are deemed as good works, or in the modern context, exemplary citizenship. Just last year we witnessed the Queen’s direct involvement in the honours system when she appointed Jean Chrétien as a member of the Order of Merit. While many commentators and officials in Canada seemed confused as to just what this honour is – the highest civil honour for service – people did realize how significant it was, in large part because it came not from a committee or politician, but directly from the Sovereign. With this paper I will delve into the central role the Crown and Sovereign play in the creation of honours and I will also explore the areas where attention and reform are required in the Canadian honours system. -

Media Culture for a Modern Nation? Theatre, Cinema and Radio in Early Twentieth-Century Scotland

Media Culture for a Modern Nation? Theatre, Cinema and Radio in Early Twentieth-Century Scotland a study © Adrienne Clare Scullion Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD to the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Faculty of Arts, University of Glasgow. March 1992 ProQuest Number: 13818929 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818929 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Frontispiece The Clachan, Scottish Exhibition of National History, Art and Industry, 1911. (T R Annan and Sons Ltd., Glasgow) GLASGOW UNIVERSITY library Abstract This study investigates the cultural scene in Scotland in the period from the 1880s to 1939. The project focuses on the effects in Scotland of the development of the new media of film and wireless. It addresses question as to what changes, over the first decades of the twentieth century, these two revolutionary forms of public technology effect on the established entertainment system in Scotland and on the Scottish experience of culture. The study presents a broad view of the cultural scene in Scotland over the period: discusses contemporary politics; considers established and new theatrical activity; examines the development of a film culture; and investigates the expansion of broadcast wireless and its influence on indigenous theatre. -

The Meritorious Service Cross 1984-2014

The Meritorious Service Cross 1984-2014 CONTACT US Directorate of Honours and Recognition National Defence Headquarters 101 Colonel By Drive Ottawa, ON K1A 0K2 http://www.cmp-cpm.forces.gc.ca/dhr-ddhr/ 1-877-741-8332 © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2014 A-DH-300-000/JD-004 Cat. No. D2-338/2014 ISBN 978-1-100-54835-7 The Meritorious Service Cross 1984-2014 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, Queen of Canada, wearing her insignia of Sovereign of the Order of Canada and of the Order of Military Merit, in the Tent Room at Rideau Hall, Canada Day 2010 Photo: Canadian Heritage, 1 July 2010 Dedication To the recipients of the Meritorious Service Cross who are the epitome of Canadian military excellence and professionalism. The Meritorious Service Cross | v Table of Contents Dedication ..................................................................................................... v Introduction ................................................................................................... vii Chapter One Historical Context ........................................................................ 1 Chapter Two Statistical Analysis ..................................................................... 17 Chapter Three Insignia and Privileges ............................................................... 37 Conclusion ................................................................................................... 55 Appendix One Letters Patent Creating the Meritorious Service Cross .............. 57 Appendix Two Regulations Governing -

“Naughty Willie” at Rhodes House

Gowers of Uganda : Conduct and Misconduct Being an abridged version of an article forthcoming in ARAS : Gowers of Uganda: The Public and Private Life of a Forgotten Colonial Governor Roger Scott, University of Queensland I Apparently, not a lot has been written about the conduct of the private lives of colonial governors. This is in contrast to the information provided in histories and novels and films about white settler society in southern and eastern Africa. In my conference contribution, I want to add to this scarce literature. My forthcoming article in ARAS has a wider compass, including an appreciation of the intersection between the public and private life of a forgotten governor of Uganda, Sir William Gowers. Both pieces draw upon original archival and obscure secondary sources examined in the context of a wider project, a biography by my wife focussed on another member of the Gowers family, her paternal grand-father, Sir Ernest Gowers. These primary sources1 provide testimony from, among others, the Prince of Wales and his aide-de-campe, that Gowers was outgoing, entertaining, and full of bravado as well as personal bravery. The same files also reveal that his personal life became a source of widespread scandal among the East African Europeans, especially missionaries, and it required the intervention of his mentor Lord Lugard to fight off his dismissal by the Colonial Secretary. William was in other words a prototype of the cliché of the romantic literature of his era: the “Black Sheep” of the family. William and his younger brother Ernest were provided with an education at Rugby and Cambridge explicitly designed for entry to the public service. -

Masculinity and Chivalry: the Tenuous Relationship of the Sacred and Secular in Medieval Arthurian Literature

MASCULINITY AND CHIVALRY: THE TENUOUS RELATIONSHIP OF THE SACRED AND SECULAR IN MEDIEVAL ARTHURIAN LITERATURE by KACI MCCOURT DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington August, 2018 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: Kevin Gustafson, Supervising Professor Jacqueline Fay James Warren i ABSTRACT Masculinity and Chivalry: The Tenuous Relationship of the Sacred and Secular in Medieval Arthurian Literature Kaci McCourt, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2018 Supervising Professors: Kevin Gustafson, Jacqueline Fay, and James Warren Concepts of masculinity and chivalry in the medieval period were socially constructed, within both the sacred and the secular realms. The different meanings of these concepts were not always easily compatible, causing tensions within the literature that attempted to portray them. The Arthurian world became a place that these concepts, and the issues that could arise when attempting to act upon them, could be explored. In this dissertation, I explore these concepts specifically through the characters of Lancelot, Galahad, and Gawain. Representative of earthly chivalry and heavenly chivalry, respectively, Lancelot and Galahad are juxtaposed in the ways in which they perform masculinity and chivalry within the Arthurian world. Chrétien introduces Lancelot to the Arthurian narrative, creating the illicit relationship between him and Guinevere which tests both his masculinity and chivalry. The Lancelot- Grail Cycle takes Lancelot’s story and expands upon it, securely situating Lancelot as the best secular knight. This Cycle also introduces Galahad as the best sacred knight, acting as redeemer for his father. Gawain, in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, exemplifies both the earthly and heavenly aspects of chivalry, showing the fraught relationship between the two, resulting in the emasculating of Gawain. -

1953 New Year Honours 1953 New Year Honours

12/19/2018 1953 New Year Honours 1953 New Year Honours The New Year Honours 1953 for the United Kingdom were announced on 30 December 1952,[1] to celebrate the year passed and mark the beginning of 1953. This was the first New Year Honours since the accession of Queen Elizabeth II. The Honours list is a list of people who have been awarded one of the various orders, decorations, and medals of the United Kingdom. Honours are split into classes ("orders") and are graded to distinguish different degrees of achievement or service, most medals are not graded. The awards are presented to the recipient in one of several investiture ceremonies at Buckingham Palace throughout the year by the Sovereign or her designated representative. The orders, medals and decorations are awarded by various honours committees which meet to discuss candidates identified by public or private bodies, by government departments or who are nominated by members of the public.[2] Depending on their roles, those people selected by committee are submitted to Ministers for their approval before being sent to the Sovereign for final The insignia of the Grand Cross of the approval. As the "fount of honour" the monarch remains the final arbiter for awards.[3] In the case Order of St Michael and St George of certain orders such as the Order of the Garter and the Royal Victorian Order they remain at the personal discretion of the Queen.[4] The recipients of honours are displayed here as they were styled before their new honour, and arranged by honour, with classes (Knight, Knight Grand Cross, etc.) and then divisions (Military, Civil, etc.) as appropriate. -

For the First Time in Sunny Hills History, the ASB Has Added a Freshman, Sophomore and Junior Princess to the Homecoming Court

the accolade VOLUME LIX, ISSUE II // SUNNY HILLS HIGH SCHOOL 1801 LANCER WAY, FULLERTON, CA 92833 // SEPT. 28, 2018 JAIME PARK | theaccolade Homecoming Royalty For the first time in Sunny Hills history, the ASB has added a freshman, sophomore and junior princess to the homecoming court. Find out about their thoughts of getting nominated on Fea- ture, page 8. Saturday’s “A Night in Athens” homecoming dance will be held for the first time in the remodeled gym. See Feature, page 9. 2 September 28, 2018 NEWS the accolade SAFE FROM STAINS Since the summer, girls restrooms n the 30s wing, 80s wing, next to Room 170 and in the Engineer- ing Pathways to Innovation and Change building have metallic ver- tical boxes from which users can select free Naturelle Maxi Pads or Naturelle Tampons. Free pads, tampons in 4 girls restrooms Fullerton Joint Union High School District installs metal box containing feminine hygiene products to comply with legislation CAMRYN PAK summer. According to the bill, the state News Editor The Fullerton Joint Union government funds these hygiene High School District sent a work- products by allocating funds to er to install pad and tampon dis- school districts throughout the *Names have been changed for pensers in the girls restrooms in state. Then, schools in need are confidentiality. the 30s wing, the 80s wing, next able to utilize these funds in order It was “that time of month” to Room 170 and in the Engineer- to provide their students with free again, and junior *Hannah Smith ing Pathways to Innovation and pads and tampons. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

Krantz [email protected] Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia + Delta Omicron = Sinfonicron G&S Works, with Date and Length of Original London Run • Thespis 1871 (63)

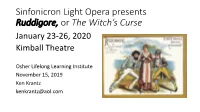

Sinfonicron Light Opera presents Ruddigore, or The Witch’s Curse January 23-26, 2020 Kimball Theatre Osher Lifelong Learning Institute November 15, 2019 Ken Krantz [email protected] Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia + Delta Omicron = Sinfonicron G&S Works, with date and length of original London run • Thespis 1871 (63) • Trial by Jury 1875 (131) • The Sorcerer 1877 (178) • HMS Pinafore 1878 (571) • The Pirates of Penzance 1879 (363) • Patience 1881 (578) • Iolanthe 1882 (398) G&S Works, Continued • Princess Ida 1884 (246) • The Mikado 1885 (672) • Ruddigore 1887 (288) • The Yeomen of the Guard 1888 (423) • The Gondoliers 1889 (554) • Utopia, Limited 1893 (245) • The Grand Duke 1896 (123) Elements of Gilbert’s stagecraft • Topsy-Turvydom (a/k/a Gilbertian logic) • Firm directorial control • The typical issue: Who will marry the soprano? • The typical competition: tenor vs. patter baritone • The Lozenge Plot • Literal lozenge: Used in The Sorcerer and never again • Virtual Lozenge: Used almost constantly Ruddigore: A “problem” opera • The horror show plot • The original spelling of the title: “Ruddygore” • Whatever opera followed The Mikado was likely to suffer by comparison Ruddigore Time: Early 19th Century Place: Cornwall, England Act 1: The village of Rederring Act 2: The picture gallery of Ruddigore Castle, one week later Ruddigore Dramatis Personae Mortals: •Sir Ruthven Murgatroyd, Baronet, disguised as Robin Oakapple (Patter Baritone) •Richard Dauntless, his foster brother, a sailor (Tenor) •Sir Despard Murgatroyd, Sir Ruthven’s younger brother -

Personalities and Perceptions: Churchill, De Gaulle, and British-Free French Relations 1940-1941" (2019)

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM Honors College Senior Theses Undergraduate Theses 2019 Personalities and Perceptions: Churchill, De Gaulle, and British- Free French Relations 1940-1941 Samantha Sullivan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses Recommended Citation Sullivan, Samantha, "Personalities and Perceptions: Churchill, De Gaulle, and British-Free French Relations 1940-1941" (2019). UVM Honors College Senior Theses. 324. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/324 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM Honors College Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Personalities and Perceptions: Churchill, De Gaulle, and British-Free French Relations 1940-1941 By: Samantha Sullivan Advised by: Drs. Steven Zdatny, Andrew Buchanan, and Meaghan Emery University of Vermont History Department Honors College Thesis April 17, 2019 Acknowledgements: Nearly half of my time at UVM was spent working on this project. Beginning as a seminar paper for Professor Zdatny’s class in Fall 2018, my research on Churchill and De Gaulle slowly grew into the thesis that follows. It was a collaborative effort that allowed me to combine all of my fields of study from my entire university experience. This project took me to London and Cambridge to conduct archival research and made for many late nights on the second floor of the Howe Library. I feel an overwhelming sense of pride and accomplishment for this thesis that is reflective of the work I have done at UVM.