MERKELDÄMMERUNG Eric Langenbacher Liminal Germany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM Honors College Senior Theses Undergraduate Theses 2018 Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany William Peter Fitz University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses Recommended Citation Fitz, William Peter, "Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany" (2018). UVM Honors College Senior Theses. 275. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/275 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM Honors College Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REACTIONARY POSTMODERNISM? NEOLIBERALISM, MULTICULTURALISM, THE INTERNET, AND THE IDEOLOGY OF THE NEW FAR RIGHT IN GERMANY A Thesis Presented by William Peter Fitz to The Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Bachelor of Arts In European Studies with Honors December 2018 Defense Date: December 4th, 2018 Thesis Committee: Alan E. Steinweis, Ph.D., Advisor Susanna Schrafstetter, Ph.D., Chairperson Adriana Borra, M.A. Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter One: Neoliberalism and Xenophobia 17 Chapter Two: Multiculturalism and Cultural Identity 52 Chapter Three: The Philosophy of the New Right 84 Chapter Four: The Internet and Meme Warfare 116 Conclusion 149 Bibliography 166 1 “Perhaps one will view the rise of the Alternative for Germany in the foreseeable future as inevitable, as a portent for major changes, one that is as necessary as it was predictable. -

Framing Through Names and Titles in German

Proceedings of the 12th Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2020), pages 4924–4932 Marseille, 11–16 May 2020 c European Language Resources Association (ELRA), licensed under CC-BY-NC Doctor Who? Framing Through Names and Titles in German Esther van den Berg∗z, Katharina Korfhagey, Josef Ruppenhofer∗z, Michael Wiegand∗ and Katja Markert∗y ∗Leibniz ScienceCampus, Heidelberg/Mannheim, Germany yInstitute of Computational Linguistics, Heidelberg University, Germany zInstitute for German Language, Mannheim, Germany fvdberg|korfhage|[email protected] fruppenhofer|[email protected] Abstract Entity framing is the selection of aspects of an entity to promote a particular viewpoint towards that entity. We investigate entity framing of political figures through the use of names and titles in German online discourse, enhancing current research in entity framing through titling and naming that concentrates on English only. We collect tweets that mention prominent German politicians and annotate them for stance. We find that the formality of naming in these tweets correlates positively with their stance. This confirms sociolinguistic observations that naming and titling can have a status-indicating function and suggests that this function is dominant in German tweets mentioning political figures. We also find that this status-indicating function is much weaker in tweets from users that are politically left-leaning than in tweets by right-leaning users. This is in line with observations from moral psychology that left-leaning and right-leaning users assign different importance to maintaining social hierarchies. Keywords: framing, naming, Twitter, German, stance, sentiment, social media 1. Introduction An interesting language to contrast with English in terms of naming and titling is German. -

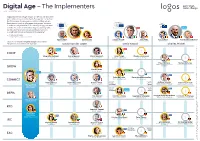

Digital Age – the Implementers 1 July – 31 December 2020

Digital Age – The Implementers 1 July – 31 December 2020 ”Digitalisation has a huge impact on the way we live, work and communicate. In some fields, Europe has to catch up – like for business to consumers – while in others we are frontrunners – such as in business to business. We have to make our single market fit for the digital age, we need Renew to make the most of artificial intelligence and big data, EPP S&D Europe we have to improve on cybersecurity and we have to work hard for our technological sovereignty.” — Ursula von der Leyen President of the European Commission Bjoern Seibert Ilze Juhansone Lorenzo Mannelli Klaus Welle François Roux Jeppe Tranholm-Mikkelsen Head of cabinet Secretary General Head of cabinet Secretary General Head of cabinet Secretary General Executive Vice-President Margrethe Vestager will coordinate the agenda on a Europe fit for the digital age. Ursula von der Leyen David Sassoli Charles Michel Renew S&D Europe COMP Margrethe Vestager Kim Jørgensen Oliver Guersent Irene Tinagli Claudia Lindemann EPP Commissioner Head of Cabinet Director General ECON Committee Chair ECON Secretariat Peter Altmaier Norbert Schultes Federal Minister of Economics Permanent Representation GROW and Energy Kerstin Jorna Greens/EFA Renew Director General Europe EPP Petra de Sutter Panos Konstantopoulos CONNECT IMCO Committee Chair IMCO Secretariat with ITRE with ITRE Thierry Breton Valère Moutarlier Roberto Viola Cristian- Peter Andreas Scheuer Stefanie Schröder Silviu Bușoi Traung Federal Minister of Transport Margrethe Commissioner -

H.E. Ms. Angela Merkel, Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany, Addresses 100Th International Labour Conference

H.E. Ms. Angela Merkel, Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany, Addresses 100th International Labour Conference In the first ever visit of a German Chancellor to the International Labour Organisation (ILO), H.E. Ms. Angela Merkel today addressed the Organization’s annual conference. Speaking to the historic 100th session of the International Labour Conference (ILC) Ms Merkel highlighted the increasing role played by the ILO in closer international cooperation. The G8 and G20 meetings would be “unthinkable without the wealth of experience of this Organisation”, she said, adding that the ILO’s involvement was the only way “to give globalization a form, a structure” (In German with subtitles in English). Transcription in English: Juan Somavia, Director-General, International Labour Organization: “Let me highlight your distinctive sense of policy coherence. Since 2007, you have regularly convened in Berlin the heads of the IMF, World Bank, WTO, OECD and the ILO, and urged us to strengthen our cooperation, and this with a view to building a strong social dimension of globalization and greater policy coherence among our mandates. These dialogues, under your guidance, have been followed up actively by the ILO with important joint initiatives with all of them, whose leaders have all addressed the Governing Body of the ILO. You have been a strong voice for a fairer, more balanced globalization in which much needs to be done by all international organizations.” Angela Merkel, Chancellor of Germany: “Universal and lasting peace can be established only if it is based on social justice.” This is the first sentence of the Constitution of the ILO and I also wish to start my speech with these words, as they clearly express what the ILO is all about and what it is trying to achieve: universal peace. -

![Detering | Was Heißt Hier »Wir«? [Was Bedeutet Das Alles?] Heinrich Detering Was Heißt Hier »Wir«? Zur Rhetorik Der Parlamentarischen Rechten](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3046/detering-was-hei%C3%9Ft-hier-%C2%BBwir%C2%AB-was-bedeutet-das-alles-heinrich-detering-was-hei%C3%9Ft-hier-%C2%BBwir%C2%AB-zur-rhetorik-der-parlamentarischen-rechten-173046.webp)

Detering | Was Heißt Hier »Wir«? [Was Bedeutet Das Alles?] Heinrich Detering Was Heißt Hier »Wir«? Zur Rhetorik Der Parlamentarischen Rechten

Detering | Was heißt hier »wir«? [Was bedeutet das alles?] Heinrich Detering Was heißt hier »wir«? Zur Rhetorik der parlamentarischen Rechten Reclam Reclams UniveRsal-BiBliothek Nr. 19619 2019 Philipp Reclam jun. Verlag GmbH, Siemensstraße 32, 71254 Ditzingen Gestaltung: Cornelia Feyll, Friedrich Forssman Druck und Bindung: Kösel GmbH & Co. KG, Am Buchweg 1, 87452 Altusried-Krugzell Printed in Germany 2019 Reclam, UniveRsal-BiBliothek und Reclams UniveRsal-BiBliothek sind eingetragene Marken der Philipp Reclam jun. GmbH & Co. KG, Stuttgart ISBn 978-3-15-019619-9 Auch als E-Book erhältlich www.reclam.de Inhalt Reizwörter und Leseweisen 7 Wir oder die Barbarei 10 Das System der Zweideutigkeit 15 Unser Deutschland, unsere Vernichtung, unsere Rache 21 Ich und meine Gemeinschaft 30 Tausend Jahre, zwölf Jahre 34 Unsere Sprache, unsere Kultur 40 Anmerkungen 50 Nachbemerkung 53 Leseempfehlungen 58 Über den Autor 60 »Sie haben die unglaubwürdige Kühnheit, sich mit Deutschland zu verwechseln! Wo doch vielleicht der Augenblick nicht fern ist, da dem deutschen Volke das Letzte daran gelegen sein wird, nicht mit ihnen verwechselt zu werden.« Thomas Mann, Ein Briefwechsel (1936) Reizwörter und Leseweisen Die Hitlerzeit – ein »Vogelschiss«; die in Hamburg gebo- rene SPD-Politikerin Aydan Özoğuz – ein Fall, der »in Ana- tolien entsorgt« werden sollte; muslimische Flüchtlinge – »Kopftuchmädchen und Messermänner«: Formulierungen wie diese haben in den letzten Jahren und Monaten im- mer von neuem für öffentliche Empörung, für Gegenreden und Richtigstellungen -

Christian Lindner Stellt Sich Den Fragen Der Gipfel-Teilnehmer

05.–07.02.2019 SCHWÄBISCH HALL EXKLUSIV: Christian Lindner stellt sich den Fragen der Gipfel-Teilnehmer Christian Lindner MdB Bundesvorsitzender der Freien Demokraten Aktuelle Informationen unter: weltmarktfuehrer-gipfel.de Mitveranstalter Ideeller Partner Christian Lindner MdB war zum Politischen Power Talk beim Gipfeltreffen der Weltmarktführer 2019 fest eingeplant, musste aus dringenden Gründen aber leider kurzfristig absagen. Fragen an Herrn Lindner konnten die Teilnehmer in Schriftform trotzdem stellen, die er uns im Nachgang gerne beantwortet hat. Lesen Sie nun, was die überwiegend mittelständischen Vertreter vom Bundesvorsitzenden der Freien Demokraten wissen wollten – sowohl auf politischer als auch auf persönlicher Ebene. WAS WOLLTEN SIE CHRISTIAN LINDNER SCHON IMMER EINMAL FRAGEN? 1 Wie starten Sie in den Tag? 12 Wenn Sie heute noch mal gründen würden – was? Ich mache Sport und gucke dabei Netflix, dann Einen digitalisierten Handwerksbetrieb. Außerdem verschaffe ich mir einen Überblick über die Medienlage glaube ich, dass die Chancen der Biologisierung als und trinke einen Espresso. zweitem Trend neben der Digitalisierung unterschätzt werden. 2 Was tun Sie für Ihre Fitness? Ganz unterschiedlich – am liebsten Rudern! 13 Welche Politiker-Kollegen wären Ihre Mitgründer in einem Start-up? 3 Was wollten Sie als kleiner Junge werden? Das kommt darauf an, was der Fokus eines Unter- Ich bin auf dem Land groß geworden und wollte immer nehmens ist. In jedem Fall unseren Schatzmeister Bauer werden – Dinge selbst in die Hand nehmen und Hermann Otto Solms, denn einen, der auf die Finanzen dabei große Fahrzeuge fahren, ein echter Traum. achtet, braucht man immer. 4 Sie haben vor kurzem den Jagdschein gemacht. 14 Gucken Sie Videos Ihrer Auftritte? Konnten Sie bereits einen kapitalen Hirsch zur Strecke Nein. -

Politische Jugendstudie Von BRAVO Und Yougov

Politische Jugendstudie von BRAVO und YouGov © 2017 YouGov Deutschland GmbH Veröffentlichungen - auch auszugsweise - bedürfen der schriftlichen Zustimmung durch die Bauer Media Group und die YouGov Deutschland GmbH. Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Zusammenfassung 2. Ergebnisse 3. Untersuchungsdesign 4. Über YouGov und Bauer Media Group © YouGov 2017 – Politische Jugendstudie von Bravo und YouGov 2 Zusammenfassung 3 Zusammenfassung I Politisches Interesse § Das politische Interesse bei den jugendlichen Deutschen zwischen 14 und 17 Jahren fällt sehr gemischt aus (ca. 1/3 stark interessiert, 1/3 mittelmäßig und 1/3 kaum interessiert). Das Vorurteil über eine politisch desinteressierte Jugend lässt sich nicht bestätigen. § Kontaktpunkte zu politischen Themen haben die Jugendlichen vor allem in der Schule (75 Prozent). An zweiter Stelle steht die Familie (57 Prozent), gefolgt von den Freunden (47 Prozent). Vor allem die politisch stark Interessierten diskutieren politische Themen auch im Internet (17 Prozent Gesamt). § Nur ein gutes Drittel beschäftigt sich intensiv und regelmäßig mit politischen Themen . Bei ähnlich vielen spielt Politik im eigenem Umfeld keine große Rolle. Dennoch erkennt der Großteil der Jugendlichen (80 Prozent) die Bedeutung von Wahlen, um die eigenen Interessen vertreten zu lassen. Eine Mehrheit (65 Prozent) wünscht sich ebenfalls mehr politisches Engagement der Menschen. Bei Jungen zeigt sich dabei eine stärkere Beschäftigung mit dem Thema Politik als bei Mädchen. Informationsverhalten § Ihrem Alter entsprechend informieren sich die Jugendlichen am häufigsten im Schulunterricht über politische Themen (51 Prozent „sehr häufig“ oder „häufig“) . An zweiter Stelle steht das Fernsehen (48 Prozent), gefolgt von Gesprächen mit Familie, Bekannten oder Freunden (43 Prozent). Mit News-Apps und sozialen Netzwerken folgen danach digitale Kanäle. Print-Ausgaben von Zeitungen und Zeitschriften spielen dagegen nur eine kleinere Rolle. -

To Chancellor Dr. Angela Merkel C/O Minister of Finance Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble C/O Vice Chancellor Sigmar Gabriel

To Chancellor Dr. Angela Merkel c/o Minister of Finance Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble c/o Vice Chancellor Sigmar Gabriel Dear Chancellor Merkel, We, the undersigned organisations from [XX] European countries are very grateful for your commitment to the financial transaction tax (FTT) in the framework of Enhanced Coopera- tion. Like you, we are of the opinion that only a broad based tax as specified in the coalition agreement and spelt out in the draft of the European Commission will be sufficiently compre- hensive. However, we are concerned that under the pressure of the finance industry some govern- ments will try to water down the proposal of the Commission. Particularly problematic would be to exempt derivatives from taxation or to tax only some of them. Derivatives represent the biggest share of transactions on the financial markets. Hence, exemptions would lead imme- diately to a substantial reduction of tax revenues. Furthermore, many derivatives are the source of dangerous stability risks and would be misused as instruments for the avoidance of the taxation of shares and bonds. We therefore ask you not to give in to the pressure of the finance industry and to tax deriva- tives as put forward in the draft proposal of the Commission. The primacy of politics over financial markets must be restored. In addition we would like to ask you to send a political signal with regard to the use of the tax revenues. We know that the German budget law does not allow the assignment of tax reve- nues for a specific purpose. However, you yourself have already stated that you could envis- age the revenues being used partly to combat youth unemployment in Europe. -

Digital Society

B56133 The Science Magazine of the Max Planck Society 4.2018 Digital Society POLITICAL SCIENCE ASTRONOMY BIOMEDICINE LEARNING PSYCHOLOGY Democracy in The oddballs of A grain The nature of decline in Africa the solar system of brain children’s curiosity SCHLESWIG- Research Establishments HOLSTEIN Rostock Plön Greifswald MECKLENBURG- WESTERN POMERANIA Institute / research center Hamburg Sub-institute / external branch Other research establishments Associated research organizations Bremen BRANDENBURG LOWER SAXONY The Netherlands Nijmegen Berlin Italy Hanover Potsdam Rome Florence Magdeburg USA Münster SAXONY-ANHALT Jupiter, Florida NORTH RHINE-WESTPHALIA Brazil Dortmund Halle Manaus Mülheim Göttingen Leipzig Luxembourg Düsseldorf Luxembourg Cologne SAXONY DanielDaniel Hincapié, Hincapié, Bonn Jena Dresden ResearchResearch Engineer Engineer at at Marburg THURINGIA FraunhoferFraunhofer Institute, Institute, Bad Münstereifel HESSE MunichMunich RHINELAND Bad Nauheim PALATINATE Mainz Frankfurt Kaiserslautern SAARLAND Erlangen “Germany,“Germany, AustriaAustria andand SwitzerlandSwitzerland areare knownknown Saarbrücken Heidelberg BAVARIA Stuttgart Tübingen Garching forfor theirtheir outstandingoutstanding researchresearch opportunities.opportunities. BADEN- Munich WÜRTTEMBERG Martinsried Freiburg Seewiesen AndAnd academics.comacademics.com isis mymy go-togo-to portalportal forfor jobjob Radolfzell postings.”postings.” Publisher‘s Information MaxPlanckResearch is published by the Science Translation MaxPlanckResearch seeks to keep partners and -

Conceptions of Terror(Ism) and the “Other” During The

CONCEPTIONS OF TERROR(ISM) AND THE “OTHER” DURING THE EARLY YEARS OF THE RED ARMY FACTION by ALICE KATHERINE GATES B.A. University of Montana, 2007 B.S. University of Montana, 2007 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures 2012 This thesis entitled: Conceptions of Terror(ism) and the “Other” During the Early Years of the Red Army Faction written by Alice Katherine Gates has been approved for the Department of Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures _____________________________________ Dr. Helmut Müller-Sievers _____________________________________ Dr. Patrick Greaney _____________________________________ Dr. Beverly Weber Date__________________ The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii Gates, Alice Katherine (M.A., Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures) Conceptions of Terror(ism) and the “Other” During the Early Years of the Red Army Faction Thesis directed by Professor Helmut Müller-Sievers Although terrorism has existed for centuries, it continues to be extremely difficult to establish a comprehensive, cohesive definition – it is a monumental task that scholars, governments, and international organizations have yet to achieve. Integral to this concept is the variable and highly subjective distinction made by various parties between “good” and “evil,” “right” and “wrong,” “us” and “them.” This thesis examines these concepts as they relate to the actions and manifestos of the Red Army Faction (die Rote Armee Fraktion) in 1970s Germany, and seeks to understand how its members became regarded as terrorists. -

Sigmund Allein Unter Feinden Amazonjs

7 Fragen an den Autor Thomas Sigmund zu seinem Buch „Allein unter Feinden? – Was der Staat für unsere Sicherheit tut – und was nicht“ Herr Sigmund, versagt der Staat beim Schutz seiner Bürger? Der Staat tut viel für die Sicherheit der Bürger. Justiz und Polizei arbeiten rund um die Uhr. Doch das alles reicht nicht. Woran machen Sie das konkret fest? Unsere innere Sicherheit ist bedroht wie noch nie seit Ende des Krieges. Einbrüche, U- Bahn-Treter, Cyberangriffe oder der Terror. Schauen Sie sich einfach die Hass- Postings im Internet, den wachsenden Rechtsextremismus oder die zunehmenden Angriffe auf Minderheiten an. Da ist etwas verrutscht in der Gesellschaft. Gibt es Gewalt nicht schon immer? Die derzeitige starke Verunsicherung der Bürger ist mehr als ein Gefühl. Eine einschneidende Zäsur waren die Vorkommnisse in der Silvesternacht in Köln 2015 an. Da waren nicht nur Polizei und Justiz weit über ihre Belastungsgrenze angekommen. Vor allem waren die Fehleinschätzungen der Politik und die mangelnde Handlungsfähigkeit des Staates erschreckend. Bis heute gibt es übrigens nur eine Handvoll Urteile gegen die Täter bei insgesamt 1200 Opfern. Doch es geht nicht nur um die Vorkommnisse auf der Kölner Domplatte Sondern? Wir haben auch eine steigende Zahl an Einbrüchen von international agierenden Einbrecherbanden aus Osteuropa, gegen die die Polizei machtlos scheint. Das einfache aber große Versprechen des Staates, das Privateigentum zu schützen ist zu oft nichts mehr wert. In den Polizeistatistiken wird zwar die Aufklärungsquote mit rund 15 Prozent beziffert; dazu zählen aber auch Fälle, die dann vor Gericht von vornherein nicht nachgewiesen werden können. So sinkt die tatsächliche Zahl auf nur rund 2,5 Prozent. -

Der Imagewandel Von Helmut Kohl, Gerhard Schröder Und Angela Merkel Vom Kanzlerkandidaten Zum Kanzler - Ein Schauspiel in Zwei Akten

Forschungsgsgruppe Deutschland Februar 2008 Working Paper Sybille Klormann, Britta Udelhoven Der Imagewandel von Helmut Kohl, Gerhard Schröder und Angela Merkel Vom Kanzlerkandidaten zum Kanzler - Ein Schauspiel in zwei Akten Inszenierung und Management von Machtwechseln in Deutschland 02/2008 Diese Veröffentlichung entstand im Rahmen eines Lehrforschungsprojektes des Geschwister-Scholl-Instituts für Politische Wissenschaft unter Leitung von Dr. Manuela Glaab, Forschungsgruppe Deutschland am Centrum für angewandte Politikforschung. Weitere Informationen unter: www.forschungsgruppe-deutschland.de Inhaltsverzeichnis: 1. Die Bedeutung und Bewertung von Politiker – Images 3 2. Helmut Kohl: „Ich werde einmal der erste Mann in diesem Lande!“ 7 2.1 Gut Ding will Weile haben. Der „Lange“ Weg ins Kanzleramt 7 2.2 Groß und stolz: Ein Pfälzer erschüttert die Bonner Bühne 11 2.3 Der richtige Mann zur richtigen Zeit: Der Mann der deutschen Mitte 13 2.4 Der Bauherr der Macht 14 2.5 Kohl: Keine Richtung, keine Linie, keine Kompetenz 16 3. Gerhard Schröder: „Ich will hier rein!“ 18 3.1 „Hoppla, jetzt komm ich!“ Schröders Weg ins Bundeskanzleramt 18 3.2 „Wetten ... dass?“ – Regieren macht Spass 22 3.3 Robin Hood oder Genosse der Bosse? Wofür steht Schröder? 24 3.4 Wo ist Schröder? Vom „Gernekanzler“ zum „Chaoskanzler“ 26 3.5 Von Saumagen, Viel-Sagen und Reformvorhaben 28 4. Angela Merkel: „Ich will Deutschland dienen.“ 29 4.1 Fremd, unscheinbar und unterschätzt – Merkels leiser Aufstieg 29 4.2 Die drei P’s der Merkel: Physikerin, Politikerin und doch Phantom 33 4.3 Zwischen Darwin und Deutschland, Kanzleramt und Küche 35 4.4 „Angela Bangbüx“ : Versetzung akut gefährdet 37 4.5 Brutto: Aus einem Guss – Netto: Zuckerguss 39 5.