Expulsion of the Palestinians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

War and Insurgency in the Western Sahara

Visit our website for other free publication downloads http://www.StrategicStudiesInstitute.army.mil/ To rate this publication click here. STRATEGIC STUDIES INSTITUTE The Strategic Studies Institute (SSI) is part of the U.S. Army War College and is the strategic-level study agent for issues relat- ed to national security and military strategy with emphasis on geostrategic analysis. The mission of SSI is to use independent analysis to conduct strategic studies that develop policy recommendations on: • Strategy, planning, and policy for joint and combined employment of military forces; • Regional strategic appraisals; • The nature of land warfare; • Matters affecting the Army’s future; • The concepts, philosophy, and theory of strategy; and, • Other issues of importance to the leadership of the Army. Studies produced by civilian and military analysts concern topics having strategic implications for the Army, the Department of Defense, and the larger national security community. In addition to its studies, SSI publishes special reports on topics of special or immediate interest. These include edited proceedings of conferences and topically-oriented roundtables, expanded trip reports, and quick-reaction responses to senior Army leaders. The Institute provides a valuable analytical capability within the Army to address strategic and other issues in support of Army participation in national security policy formulation. Strategic Studies Institute and U.S. Army War College Press WAR AND INSURGENCY IN THE WESTERN SAHARA Geoffrey Jensen May 2013 The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. -

Jews on Route to Palestine 1934-1944. Sketches from the History of Aliyah

JEWS ON ROUTE TO PALESTINE 1934−1944 JAGIELLONIAN STUDIES IN HISTORY Editor in chief Jan Jacek Bruski Vol. 1 Artur Patek JEWS ON ROUTE TO PALESTINE 1934−1944 Sketches from the History of Aliyah Bet – Clandestine Jewish Immigration Jagiellonian University Press Th e publication of this volume was fi nanced by the Jagiellonian University in Krakow – Faculty of History REVIEWER Prof. Tomasz Gąsowski SERIES COVER LAYOUT Jan Jacek Bruski COVER DESIGN Agnieszka Winciorek Cover photography: Departure of Jews from Warsaw to Palestine, Railway Station, Warsaw 1937 [Courtesy of National Digital Archives (Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe) in Warsaw] Th is volume is an English version of a book originally published in Polish by the Avalon, publishing house in Krakow (Żydzi w drodze do Palestyny 1934–1944. Szkice z dziejów alji bet, nielegalnej imigracji żydowskiej, Krakow 2009) Translated from the Polish by Guy Russel Torr and Timothy Williams © Copyright by Artur Patek & Jagiellonian University Press First edition, Krakow 2012 All rights reserved No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any eletronic, mechanical, or other means, now know or hereaft er invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers ISBN 978-83-233-3390-6 ISSN 2299-758X www.wuj.pl Jagiellonian University Press Editorial Offi ces: Michałowskiego St. 9/2, 31-126 Krakow Phone: +48 12 631 18 81, +48 12 631 18 82, Fax: +48 12 631 18 83 Distribution: Phone: +48 12 631 01 97, Fax: +48 12 631 01 98 Cell Phone: + 48 506 006 674, e-mail: [email protected] Bank: PEKAO SA, IBAN PL80 1240 4722 1111 0000 4856 3325 Contents Th e most important abbreviations and acronyms ........................................ -

In the Name of Socialism: Zionism and European Social Democracy in the Inter-War Years

In the Name of Socialism: Zionism and European Social Democracy in the Inter-War Years PAUL KELEMEN* Summary: Since 1917, the European social democratic movement has given fulsome support to Zionism. The article examines the ideological basis on which Zionism and, in particular, Labour Zionism gained, from 1917, the backing of social democratic parties and prominent socialists. It argues that Labour Zionism's appeal to socialists derived from the notion of "positive colonialism". In the 1930s, as the number of Jewish refugees from Nazi persecution increased considerably, social democratic pro-Zionism also came to be sustained by the fear that the resettlement of Jews in Europe would strengthen anti-Semitism and the extreme right. The social democratic movement was an important source of political support for the setting up of a Jewish state in Palestine. Yet its attitude to Zionism has been noted mostly en passant in works tracing the socialist, and in particular the Marxist, interpretations of the Jewish question.1 The lack of attention accorded to this issue stems partly from the pre-1914 socialist theoreticians themselves, most of whom considered Zionism, simultaneously, as a diversion from the class struggle and a peripheral issue. In the inter-war years, however, prominent socialists, individual social democratic parties and their collective organizations established a tradition of pro-Zionism. The aim, here, is to trace the ideas and political factors which shaped this tradition. Before World War I, sympathy for Zionism in the socialist movement was confined to its fringe: articles favourable to Jewish nationalism appeared, from 1908, in Sozialistische Monatshefte, a journal edited by Joseph Bloch and influential on the revisionist right wing of the German Social Democratic Party.2 Bloch's belief that the sense of national com- munity transcended class interest as a historical force, accorded with interpreting the Jewish question in national rather than class terms. -

Steps to Statehood Timeline

STEPS TO STATEHOOD TIMELINE Tags: History, Leadership, Balfour, Resources 1896: Theodor Herzl's publication of Der Judenstaat ("The Jewish State") is widely considered the foundational event of modern Zionism. 1917: The British government adopted the Zionist goal with the Balfour Declaration which views with favor the creation of "a national home for the Jewish people." / Balfour Declaration Feb. 1920: Winston Churchill: "there should be created in our own lifetime by the banks of the Jordan a Jewish State." Apr. 1920: The governments of Britain, France, Italy, and Japan endorsed the British mandate for Palestine and also the Balfour Declaration at the San Remo conference: The Mandatory will be responsible for putting into effect the declaration originally made on November 8, 1917, by the British Government, and adopted by the other Allied Powers, in favour of the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people. July 1922: The League of Nations further confirmed the British Mandate and the Balfour Declaration. 1937: Lloyd George, British prime minister when the Balfour Declaration was issued, clarified that its purpose was the establishment of a Jewish state: it was contemplated that, when the time arrived for according representative institutions to Palestine, / if the Jews had meanwhile responded to the opportunities afforded them ... by the idea of a national home, and had become a definite majority of the inhabitants, then Palestine would thus become a Jewish commonwealth. July 1937: The Peel Commission: 1. "if the experiment of establishing a Jewish National Home succeeded and a sufficient number of Jews went to Palestine, the National Home might develop in course of time into a Jewish State." 2. -

Israel in 1982: the War in Lebanon

Israel in 1982: The War in Lebanon by RALPH MANDEL LS ISRAEL MOVED INTO its 36th year in 1982—the nation cele- brated 35 years of independence during the brief hiatus between the with- drawal from Sinai and the incursion into Lebanon—the country was deeply divided. Rocked by dissension over issues that in the past were the hallmark of unity, wracked by intensifying ethnic and religious-secular rifts, and through it all bedazzled by a bullish stock market that was at one and the same time fuel for and seeming haven from triple-digit inflation, Israelis found themselves living increasingly in a land of extremes, where the middle ground was often inhospitable when it was not totally inaccessible. Toward the end of the year, Amos Oz, one of Israel's leading novelists, set out on a journey in search of the true Israel and the genuine Israeli point of view. What he heard in his travels, as published in a series of articles in the daily Davar, seemed to confirm what many had sensed: Israel was deeply, perhaps irreconcilably, riven by two political philosophies, two attitudes toward Jewish historical destiny, two visions. "What will become of us all, I do not know," Oz wrote in concluding his article on the develop- ment town of Beit Shemesh in the Judean Hills, where the sons of the "Oriental" immigrants, now grown and prosperous, spewed out their loath- ing for the old Ashkenazi establishment. "If anyone has a solution, let him please step forward and spell it out—and the sooner the better. -

The British Labour Party and Zionism, 1917-1947 / by Fred Lennis Lepkin

THE BRITISH LABOUR PARTY AND ZIONISM: 1917 - 1947 FRED LENNIS LEPKIN BA., University of British Columbia, 196 1 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History @ Fred Lepkin 1986 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY July 1986 All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. Name : Fred Lennis Lepkin Degree: M. A. Title of thesis: The British Labour Party and Zionism, - Examining Committee: J. I. Little, Chairman Allan B. CudhgK&n, ior Supervisor . 5- - John Spagnolo, ~upervis&y6mmittee Willig Cleveland, Supepiso$y Committee -Lenard J. Cohen, External Examiner, Associate Professor, Political Science Dept.,' Simon Fraser University Date Approved: August 11, 1986 PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of Thesis/Project/Extended Essay The British Labour Party and Zionism, 1917 - 1947. -

The 1948 Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE The 1948 ethnic cleansing of Palestine AUTHORS Pappé, I JOURNAL Journal of Palestine Studies DEPOSITED IN ORE 17 July 2014 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10871/15208 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication The 1948 Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine Author(s): Ilan Pappé Source: Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 36, No. 1 (Autumn 2006), pp. 6-20 Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the Institute for Palestine Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/jps.2006.36.1.6 . Accessed: 28/03/2014 09:50 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press and Institute for Palestine Studies are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Palestine Studies. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 144.173.152.98 on Fri, 28 Mar 2014 09:50:03 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions THE 1948 ETHNIC CLEANSING OF PALESTINE ILAN PAPP´E This article, excerpted and adapted from the early chapters of a new book, emphasizes the systematic preparations that laid the ground for the expulsion of more than 750,000 Palestinians from what became Israel in 1948. -

CA 6821/93 Bank Mizrahi V. Migdal Cooperative Village 1

CA 6821/93 Bank Mizrahi v. Migdal Cooperative Village 1 CA 6821/93 LCA 1908/94 LCA 3363/94 United Mizrahi Bank Ltd. v. 1. Migdal Cooperative Village 2. Bostan HaGalil Cooperative Village 3. Hadar Am Cooperative Village Ltd 4. El-Al Agricultural Association Ltd. CA 6821/93 1. Givat Yoav Workers Village for Cooperative Agricultural Settlement Ltd 2. Ehud Aharonov 3. Aryeh Ohad 4. Avraham Gur 5. Amiram Yifhar 6. Zvi Yitzchaki 7. Simana Amram 8. Ilan Sela 9. Ron Razon 10. David Mini v. 1. Commercial Credit Services (Israel) Ltd 2. The Attorney General LCA 1908/94 1. Dalia Nahmias 2. Menachem Nahmias v. Kfar Bialik Cooperative Village Ltd LCA 3363/94 The Supreme Court Sitting as the Court of Civil Appeals [November 9, 1995] Before: Former Court President M. Shamgar, Court President A. Barak, Justices D. Levine, G. Bach, A. Goldberg, E. Mazza, M. Cheshin, Y. Zamir, Tz. E Tal Appeal before the Supreme Court sitting as the Court of Civil Appeals 2 Israel Law Reports [1995] IsrLR 1 Appeal against decision of the Tel-Aviv District Court (Registrar H. Shtein) on 1.11.93 in application 3459/92,3655, 4071, 1630/93 (C.F 1744/91) and applications for leave for appeal against the decision of the Tel-Aviv District Court (Registrar H. Shtein) dated 6.3.94 in application 5025/92 (C.F. 2252/91), and against the decision of the Haifa District Court (Judge S. Gobraan), dated 30.5.94 in application for leave for appeal 18/94, in which the appeal against the decision of the Head of the Execution Office in Haifa was rejected in Ex.File 14337-97-8-02. -

The Israel/Palestine Question

THE ISRAEL/PALESTINE QUESTION The Israel/Palestine Question assimilates diverse interpretations of the origins of the Middle East conflict with emphasis on the fight for Palestine and its religious and political roots. Drawing largely on scholarly debates in Israel during the last two decades, which have become known as ‘historical revisionism’, the collection presents the most recent developments in the historiography of the Arab-Israeli conflict and a critical reassessment of Israel’s past. The volume commences with an overview of Palestinian history and the origins of modern Palestine, and includes essays on the early Zionist settlement, Mandatory Palestine, the 1948 war, international influences on the conflict and the Intifada. Ilan Pappé is Professor at Haifa University, Israel. His previous books include Britain and the Arab-Israeli Conflict (1988), The Making of the Arab-Israeli Conflict, 1947–51 (1994) and A History of Modern Palestine and Israel (forthcoming). Rewriting Histories focuses on historical themes where standard conclusions are facing a major challenge. Each book presents 8 to 10 papers (edited and annotated where necessary) at the forefront of current research and interpretation, offering students an accessible way to engage with contemporary debates. Series editor Jack R.Censer is Professor of History at George Mason University. REWRITING HISTORIES Series editor: Jack R.Censer Already published THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION AND WORK IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY EUROPE Edited by Lenard R.Berlanstein SOCIETY AND CULTURE IN THE -

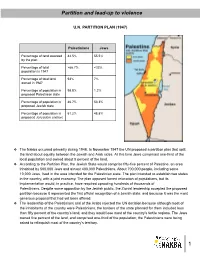

Partition and Lead-Up to Violence

P artition and leadup to violence U.N. PARTITION PLAN (1947) Palestinians Jews Percentage of land awarded 44.5% 55.5% by the plan Percentage of total >66.7% <33% population in 1947 Percentage of total land 93% 7% owned in 1947 Percentage of population in 98.8% 1.2% proposed Palestinian state Percentage of population in 46.7% 53.3% proposed Jewish state Percentage of population in 51.2% 48.8% proposed Jerusalem enclave ❖ The Nakba occurred primarily during 1948. In November 1947 the UN proposed a partition plan that split the land about equally between the Jewish and Arab sides. At this time Jews comprised onethird of the local population and owned about 5 percent of the land. ❖ According to the Partition Plan, the Jewish State would comprise fiftyfive percent of Palestine, an area inhabited by 500,000 Jews and almost 400,000 Palestinians. About 700,000 people, including some 10,000 Jews, lived in the area intended for the Palestinian state. The plan intended to establish two states in the country, with a joint economy. The plan opposed forced relocation of populations, but its implementation would, in practice, have required uprooting hundreds of thousands of Palestinians. Despite some opposition by the Jewish public, the Zionist leadership accepted the proposed partition because it represented the first official recognition of a Jewish state, and because it was the most generous proposal that had yet been offered. ❖ The leadership of the Palestinians and of the Arabs rejected the UN decision because although most of the inhabitants of the country were Palestinians, the borders of the state planned for them included less than fifty percent of the country’s land, and they would lose most of the country’s fertile regions. -

The Signatories of the Israel Declaration of Independence

Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs The Signatories of the Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel The British Mandate over Palestine was due to end on May 15, 1948, some six months after the United Nations had voted to partition Palestine into two states: one for the Jews, the other for the Arabs. While the Jews celebrated the United Nations resolution, feeling that a truncated state was better than none, the Arab countries rejected the plan, and irregular attacks of local Arabs on the Jewish population of the country began immediately after the resolution. In the United Nations, the US and other countries tried to prevent or postpone the establishment of a state, suggesting trusteeship, among other proposals. But by the time the British Mandate was due to end, the United Nations had not yet approved any alternate plan; officially, the partition plan was still "on the books." A dilemma faced the leaders of the yishuv, the Jewish community in Palestine. Should they declare the country's independence upon the withdrawal of the British mandatory administration, despite the threat of an impending attack by Arab states? Or should they wait, perhaps only a month or two, until conditions were more favorable? Under the leadership of David Ben-Gurion, who was to become the first Prime Minister of Israel, theVa'ad Leumi - the representative body of the yishuv under the British mandate - decided to seize the opportunity. At 4:00 PM on Friday, May 14, the national council, which had directed the Jewish community's affairs under the British Mandate, met in the Tel Aviv Museum on Rothschild Boulevard in Tel Aviv. -

The Imbalance of Empathy in the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict: Reflections from the (Simulated) Negotiating Table

The Imbalance of Empathy in the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict: Reflections from the (Simulated) Negotiating Table Dan Zafrir THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS Every academic year ICSR is offering six young leaders from Israel and Palestine the opportunity to come to London for a period of two months in order to develop their ideas on how to further mutual understanding in their region through addressing both themselves and “the other”, as well as engaging in research, debate and constructive dialogue in a neutral academic environment. The end result is a short paper that will provide a deeper understanding and a new perspective on a specific topic or event that is personal to each Fellow. Author: Dan Zafrir, 2017 Through the Looking Glass Fellow, ICSR. The views expressed here are solely those of the author and do not reflect those of the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation. Editor: Katie Rothman, ICSR CONTACT DETAILS Like all other ICSR publications, this report can be downloaded free of charge from the ICSR website at www.icsr.info. For questions, queries and additional copies of the report, please contact: ICSR King’s College London Strand London WC2R 2LS United Kingdom T. +44 (0)20 7848 2065 E. [email protected] For news and updates, follow ICSR on Twitter: @ICSR_Centre. © ICSR 2017 The Imbalance of Empathy in the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict: Reflections from the (Simulated) Negotiating Table Contents Introduction 3 Empathy Starts with the Self 4 The Opening of the Israeli Mind… 5 … And the Closing of the Palestinian One 7 Empathizing with the Past to Establish a Future (i.e.: Policy Recommendations) 8 Conclusion 9 Reference List 10 1 The Imbalance of Empathy in the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict: Reflections from the (Simulated) Negotiating Table 2 The Imbalance of Empathy in the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict: Reflections from the (Simulated) Negotiating Table The Imbalance of Empathy in the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict: Reflections from the (Simulated) Negotiating Table Introduction mpathy is often regarded as a key feature of social life.