Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newbery Medal Winners, 1922 – Present

Association for Library Service to Children Newbery Medal Winners, 1922 – Present 2019: Merci Suárez Changes Gears, written by Meg Medina (Candlewick Press) 2018: Hello, Universe, written by Erin Entrada Kelly (Greenwillow Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers) 2017: The Girl Who Drank the Moon by Kelly Barnhill (Algonquin Young Readers/Workman) 2016: Last Stop on Market Street by Matt de la Peña (G.P. Putnam's Sons/Penguin) 2015: The Crossover by Kwame Alexander (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) 2014: Flora & Ulysses: The Illuminated Adventures by Kate DiCamillo (Candlewick Press) 2013: The One and Only Ivan by Katherine Applegate (HarperCollins Children's Books) 2012: Dead End in Norvelt by Jack Gantos (Farrar Straus Giroux) 2011: Moon over Manifest by Clare Vanderpool (Delacorte Press, an imprint of Random House Children's Books) 2010: When You Reach Me by Rebecca Stead, published by Wendy Lamb Books, an imprint of Random House Children's Books. 2009: The Graveyard Book by Neil Gaiman, illus. by Dave McKean (HarperCollins Children’s Books) 2008: Good Masters! Sweet Ladies! Voices from a Medieval Village by Laura Amy Schlitz (Candlewick) 2007: The Higher Power of Lucky by Susan Patron, illus. by Matt Phelan (Simon & Schuster/Richard Jackson) 2006: Criss Cross by Lynne Rae Perkins (Greenwillow Books/HarperCollins) 2005: Kira-Kira by Cynthia Kadohata (Atheneum Books for Young Readers/Simon & Schuster) 2004: The Tale of Despereaux: Being the Story of a Mouse, a Princess, Some Soup, and a Spool of Thread by Kate DiCamillo (Candlewick Press) 2003: Crispin: The Cross of Lead by Avi (Hyperion Books for Children) 2002: A Single Shard by Linda Sue Park(Clarion Books/Houghton Mifflin) 2001: A Year Down Yonder by Richard Peck (Dial) 2000: Bud, Not Buddy by Christopher Paul Curtis (Delacorte) 1999: Holes by Louis Sachar (Frances Foster) 1998: Out of the Dust by Karen Hesse (Scholastic) 1997: The View from Saturday by E.L. -

Gathering Blue, and the Ways in Which Different Characters Have Power Over Each Other

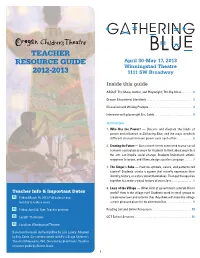

TEACHER RESOURCE GUIDE April 30-May 17, 2013 Winningstad Theatre 2012-2013 1111 SW Broadway Inside this guide ABOUT: The Show, Author, and Playwright; The Big Ideas ........2 Oregon Educational Standards .................................3 Discussion and Writing Prompts................................4 Interview with playwright Eric Coble............................5 Activities 1. Who Has the Power? — Discuss and diagram the kinds of power and influence in Gathering Blue, and the ways in which different characters have power over each other. ..........6 2. Creating the Future — Use current events connected to your social sciences curriculum as ways for students to think about ways that the arts can inspire social change. Students brainstorm artistic responses to issues, and if time, design a poster campaign. ......7 3. The Singer’s Robe — How do symbols, colors, and patterns tell stories? Students create a square that visually expresses their identity, history, or a story about themselves. Then put the squares together to create a visual history of your class................8 4. Laws of the Village — What kind of government controls Kira’s Teacher Info & Important Dates world? How is the village run? Students work in small groups to Friday, March 15, 2013: Full balance due, create new laws and reforms that they think will make the village last day to reduce seats a more pleasant place for its citizens to live. ..................9 Friday, April 26, 7pm: Teacher preview Reading List and Online Resources ............................10 Length: 75 minutes OCT School Services .........................................12 Location: Winningstad Theatre Based on the book Gathering Blue by Lois Lowry. Adapted by Eric Coble. Co-commissioned with First Stage Children’s Theatre (Milwaukee, WI). -

7Th Grade Required Reading List the Giver By Lois Lowry The

th 7 Grade Required Reading List The Giver by Lois Lowry The Pearl by John Steinbeck The Boy in the Striped Pajamas by John Boyne The City of Ember by Jeanne DuPrau During one grading period, students will select a book to read from a list given by the teacher . During one grading period, students will read a book of choice approved by the teacher. th 8 Grade Required Reading List The Outsiders by S.E. Hinton The Old Man and the Sea by Ernest Hemingway To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee Sounder by William Armstrong During one grading period, students will select a book to read from a list given by the teacher. During one grading period, students will read a book of choice approved by the teacher. th 9 Grade Required Reading List Monster by Walter Dean Myers Gods, Heroes and Men of Ancient Greece by W.H.D. Rouse Lord of the Flies by William Golding A Raisin in the Sun by Lorraine Hansberry A Rose for Emily by William Faulkner th 10 Grade Required Reading List A Walk to Remember by Nicholas Sparks The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald No Fear: The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne The Wave by Todd Strasser Our Town by Thornton Wilder th 11 Grade Required Reading List Hound of the Baskervilles by Arthur Conan Doyle The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson Turn of the Screw by Henry James 1984 by George Orwell Frankenstein by Mary Shelley th 12 Grade Required Reading List And Then There Were None by Agatha Christie Antigone and Oedipus Rex by Sophocles The Island of Dr. -

6Th Graders • Hatchet by Gary Paulsen (REQUIRED) • Sounder by William H

Dear Parents and Students, Summer is just around the corner and it is that 4me again to prepare for our summer reading assignment and project. All middle school students will be required to read one book during the summer months. We encourage the students to read addional books and have listed a few suggesons for each grade level. Each of these books are entertaining as well as educa4onal. Listed below are the suggested and required book for each grade level. Incoming 6th Graders • Hatchet by Gary Paulsen (REQUIRED) • Sounder by William H. Armstrong • The True Confessions of CharloPe Doyle by Avi Incoming 7th Graders • Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson • Call it Courage by Armstrong Sperry (Required) • The Pigman by Paul Zindel Incoming 8th Grade • Animal Farm by George Orwell • The Giver by Lois Lowry (Required) • The Tell- Tale Heart by Edgar Allan Poe Upon returning to school in the fall, a project for one required book will be due. This will be their first grade of the year. Students are urged to read at least two other books of their choice. Please see the back of this paper for the selected summer reading projects. Pick one and have fun with it! If you need any addional clarifica4on, I can be reached at [email protected] Sincerely, Mrs. Hilsenbeck SUMMER READING PROJECTS T-SHIRT BOOK REPORT You will demonstrate your under- standing of the novel by designing a t- shirt! You may use markers, paint, iron- NEW ENDING ons, sewn on items, etc. Be sure to use complete sentences. Check for Didn’t like the ending of your novel? Write spelling, grammar, punctua4on, and a new one!(or write an epilogue: explain capitaliza4on. -

Maniac Magee

Maniac Magee BY Jerry Spinelli Summary ….…. ………………………………2 About the Author……………………… .. 3 Book Reviews………………………… ……. 5 Discussion Questions……………… ….. 6 Author Interview……………………… …. 8 Further Reading……………………… ….. 9 SUMMARY _______________________________ He wasn't born with the name Maniac Magee. He came into this world named Jeffrey Lionel Magee, but when his parents died and his life changed, so did his name. And Maniac Magee became a legend. Even today kids talk about how fast he could run; about how he hit an inside-the-park "frog" homer; how no knot, no matter how snarled, would stay that way once he began to untie it. But the thing Maniac Magee is best known for is what he did for the kids from the East Side and those from the West Side. He was special all right, and this is his story, and it's a story that is very careful not to let the facts get mixed up with the truth. From Scholastic Authors and Books http://www2.scholastic.com/teachers/authorsandbooks/teachingwithbooks/producth ome.jhtml?productID=10893&displayName=Description (Accessed 8/04/05) Awards 1991 Newbery Medal 1990 Boston Globe–Horn Book Award 1991 Notable Children’s Books (ALA) 1991 Best Books for Young Adults (ALA) 1990 Children’s Editors’ Choices ( Booklist ) 2 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Jerry Spinelli's Biography Born: February 1, 1941 in Norristown , PA , United States Current Home: Phoenixville , PA When I was growing up, the first thing I wanted to be was a cowboy. That lasted till I was about ten. Then I wanted to be a baseball player. Preferably shortstop for the New York Yankees. -

Giver Lit Plans.Pdf

TEACHER’S PET PUBLICATIONS LitPlan Teacher Pack™ for The Giver based on the book by Lois Lowry Written by Barbara M. Linde, MA Ed. © 1997 Teacher’s Pet Publications, Inc. All Rights Reserved This LitPlan for Lois Lowry’s The Giver has been brought to you by Teacher’s Pet Publications, Inc. Copyright Teacher’s Pet Publications 1997 Only the student materials in this unit plan (such as worksheets, study questions, and tests) may be reproduced multiple times for use in the purchaser’s classroom. For any additional copyright questions, contact Teacher’s Pet Publications. www.tpet.com TABLE OF CONTENTS - The Giver Introduction 6 Unit Objectives 8 Unit Outline 9 Reading Assignment Sheet 10 Study Questions 13 Quiz/Study Questions (Multiple Choice) 24 Pre-Reading Vocabulary Worksheets 45 Lesson One (Introductory Lesson) 61 Nonfiction Assignment Sheet 68 Oral Reading Evaluation Form 71 Writing Assignment 1 73 Writing Evaluation Form 75 Writing Assignment 2 79 Writing Assignment 3 86 Extra Writing Assignments/Discussion ?s 88 Vocabulary Review Activities 95 Unit Review Activities 97 Unit Tests 105 Unit Resource Materials 139 Vocabulary Resource Materials 155 3 A FEW NOTES ABOUT THE AUTHOR LOWRY, LOIS (1937-). Lois Lowry is the author of over twenty juvenile novels, and has contributed stories, articles, and photographs to many leading periodicals. Her literary awards are numerous and extensive. She once said that she gauges her success as a writer by her ability to "help adolescents answer their own questions about life, identity, and human relationships." Lois Lowry was born on March 20, 1937, in Honolulu, Hawaii. -

The Newbery Medal Is Awarded Annually by the American Library Association (ALA) for the Most Distinguished American Children's Book Published the Previous Year

NeWbERY Medal Books The Newbery Medal is awarded annually by the American Library Association (ALA) for the most distinguished American children's book published the previous year. It was created in 1922, named after the eighteenth-century English bookseller John Newbery, to be the first children's book award in the world. It is selected each year by the Children's Librarians' Section of the ALA and has become the best known and most discussed children's book award in America. Holdings found in the library are featured in red. 2017: The Girl who Drank the Moon by Kelly Barnhill* 2016: Last Stop on Market Street by Matt de la Pena 2015: The Crossover by Kwame Alexander* 2014: Flora and Ulysses: the Illuminated Adventures by Kate DiCamillo* 2013: The One and Only Ivan by Katherine Applegate* 2012: Dead End in Norvelt by Jack Gantos* 2011: Moon Over Manifest by Clare Vanderpool* 2010: When You Reach Me by Rebecca Stead* 2009: The Graveyard Book by Neil Gaiman* 2008: Good Masters! Sweet Ladies! Voices from a Medieval Village by Laura Amy Schlitz 2007: The Higher Power of Lucky by Susan Patron* 2006: Criss Cross by Lynne Rae Perkins* 2005: Kira-Kira by Cynthia Kadohata* 2004: The Tale of Despereaux by Kate DiCamillo* 2003: Crispin by Avi* 2002: A Single Shard by Linda Sue Park * 2001: A Year Down Yonder by Richard Peck * 2000: Bud, Not Buddy by Christopher Paul Curtis * 1999: Holes by Louis Sachar * 1998: Out of the Dust by Karen Hesse * 1997: The View from Saturday by E.L. Konigsburg * 1996: The Midwife’s Apprentice by Karen Cushman* 1995: Walk Two Moons by Sharon Creech * 1994: The Giver by Lois Lowry* 1993: Missing May by Cynthia Rylant * 1992: Shiloh by Phyllis Reynolds Naylor * 1991: Maniac Magee by Jerry Spinelli * 1990: Number the Stars by Lois Lowry * 1989: Joyful Noise: Poems for Two Voices by Paul Fleischman * 1988: Lincoln: A Photobiography by Russell Freedman * 1987: The Whipping Boy by Sid Fleischman * 1986: Sarah, Plain and Tall by Patricia MacLachlan* 1985: The Hero and the Crown by Robin McKinley 1984: Dear Mr. -

Newbery Award Winners Newbery Award Winners

Waterford Public Library Newbery Award Winners Newbery Award Winners 1959: The Witch of Blackbird Pond by Elizabeth George Speare 1958: Rifles for Watie by Harold Keith Newbery Award Winners 1996: The Midwife's Apprentice by Karen Cushman 1957: Miracles on Maple Hill by Virginia Sorenson 1995: Walk Two Moons by Sharon Creech 1956: Carry On, Mr. Bowditch by Jean Lee Latham 1994: The Giver by Lois Lowry 1955: The Wheel on the School by Meindert DeJong The Newbery Medal was named for 18th-century British bookseller 1993: Missing May by Cynthia Rylant 1954: ...And Now Miguel by Joseph Krumgold John Newbery. It is awarded annually by the Association for 1992: Shiloh by Phyllis Reynolds Naylor 1953: Secret of the Andes by Ann Nolan Clark Library Service to Children, a division of the American Library 1991: Maniac Magee by Jerry Spinelli 1952: Ginger Pye by Eleanor Estes Association, to the author of the most distinguished contribution to 1990: Number the Stars by Lois Lowry 1951: Amos Fortune, Free Man by Elizabeth Yates American literature for children. 1989: Joyful Noise: Poems for Two Voices by Paul Fleischman 1950: The Door in the Wall by Marguerite de Angeli 1988: Lincoln: A Photobiography by Russell Freedman 1949: King of the Wind by Marguerite Henry 2021: When You Trap a Tiger by Tae Keller 1987: The Whipping Boy by Sid Fleischman 1948: The Twenty-One Balloons by William Pène du Bois 1986: Sarah, Plain and Tall by Patricia MacLachlan 1947: Miss Hickory by Carolyn Sherwin Bailey 2020: New Kid, written and illustrated by Jerry Craft 1985: The Hero and the Crown by Robin McKinley 1946: Strawberry Girl by Lois Lenski 2019: Merci Suárez Changes Gears by Meg Medina 1984: Dear Mr. -

The Giver (Questions)

The Giver (Questions) 1. In The Giver, each family has two parents, a son, and a daughter. The relationships are not biological but are developed through observation and a careful handling of personality. In our own society, the makeup of family is under discussion. How are families defined? Are families the foundations of a society, or are they continually open for new definitions? 2. In Jonas’s community, every person and his or her experience are precisely the same. The climate is controlled, and competition has been eliminated in favor of a community in which everyone works only for the common good. What advantages might “Sameness” yield for contemporary communities? Is the loss of diversity worthwhile? 3. Underneath the placid calm of Jonas’s society lies a very orderly and inexorable system of euthanasia, practiced on the very young who do not conform, the elderly, and those whose errors threaten the stability of the community. What are the disadvantages and benefits of a community that accepts such a vision of euthanasia? 4. Why is the relationship between Jonas and The Giver dangerous, and what does this danger suggest about the nature of love? 5. The ending of The Giver may be interpreted in two very different ways. Perhaps Jonas is remembering his Christmas memory—one of the most beautiful that The Giver transmitted to him—as he and Gabriel are freezing to death, falling into a dreamlike coma in the snow. Or perhaps Jonas does hear music and, with his special vision, is able to perceive the warm house where people are waiting to greet him. -

The Giver by Lois Lowry Essay Choices A2

The Giver by Lois Lowry Essay Choices A2 Directions: Choose one of the following topics. Develop an essay responding to the question of your choice. 1. Lois Lowry left the ending of The Giver purposefully ambiguous. There are a number of possibilities as to what happened at the end of the novel. What do you believe happens to Jonas and Gabe at the end of the novel? 2. The Giver received the Newbery Award in 1994. The Newbery Award is given to books for children that make a distinguished contribution to American literature. In identifying “distinguished contribution to American literature,” defined as text, in a book for children, a. Committee members need to consider the following: Interpretation of the theme or concept Presentation of information including accuracy, clarity, and organization Development of a plot Delineation of characters Delineation of a setting Appropriateness of style. Note: Because the literary qualities to be considered will vary depending on content, the committee need not expect to find excellence in each of the named elements. The book should, however, have distinguished qualities in all of the elements pertinent to it. b. Committee members must consider excellence of presentation for a child audience. 2. Each book is to be considered as a contribution to American literature. The committee is to make its decision primarily on the text. Other components of a book, such as illustrations, overall design of the book, etc., may be considered when they make the book less effective. 3. The book must be a self-contained entity, not dependent on other media (i.e., sound or film equipment) for its enjoyment. -

Gathering Blue by Lois Lowry

EDUCATOR’S GUIDE Gathering Blue by Lois LOWry Correlates to Common Core Language Arts Standards in Reading: Literature: Key Ideas & Details RL. 6-8.2; Writing: Text Types & LOIS LOWRY Purposes W. 6-8.1; Speaking & Listening: Presentation of Knowledge & Ideas SL. 6-8.4. “Mother?” There was no reply. She hadn’t expected one. Her mother had been dead, now, for four days, and Kira could tell that the last of the spirit was drifting away . Now she was all alone. CLASSROOM DISCUSSION Left orphaned and physically fl awed in a civilization that shuns and discards the weak, Kira faces a frighteningly uncertain future. Her neighbors are hostile and no one but a small boy off ers to help. • Fear plagues the people of Kira’s community. What do When she is summoned to judgment by the Council of Guardians, GATHERING BLUE Kira prepares to fi ght for her life. But the Council, to her surprise, has they fear the most? How do the Guardians exploit their plans for her. Blessed with an almost magical talent that keeps her alive, the young girl faces new responsibilities and a set of mysteries deep fears? within the only world she has ever known. On her quest for truth, Kira discovers things that will change her life and world forever. • Why are the women fearful of Vandara? Debate whether ★ “A wonderful tale of deceit, loyalty, community, strength of character, and Kira’s search for truth.” Vandara is a bully. What in her past life turned her into —BOOK REPORT, starred review a bitter woman? How is she the “ringleader” in turning ★ “Lowry is a master at creating worlds, both real and imagined.” —BOOKLIST, starred review the women against Kira? Vandara takes Kira before the Council of Guardians. -

Newbery Award

Newbery Medal Winners, 1922 - 2020 2020: New Kid by Jerry Craft JUV CRA 2019: Merci Suárez Changes Gears by Meg Medina JUV MED 2018: Hello, Universe by Erin Entrada Kelly JUV KEL 2017: The Girl Who Drank the Moon by Kelly Barnhill JUV BAR 2016: Last Stop on Market Street by Matt de la Peña E DEL 2015: The Crossover by Kwame Alexander JUV ALE 2014: Flora & Ulysses: The Illuminated Adventures by Kate DiCamillo JUV DIC 2013: The One and Only Ivan by Katherine Applegate JUV APP 2012: Dead End in Norvelt by Jack Gantos JUV GAN 2011: Moon over Manifest by Clare Vanderpool JUV VAN 2010: When You Reach Me by Rebecca Stead JUV STE 2009: The Graveyard Book by Neil Gaiman JUV GAI 2008: Good Masters! Sweet Ladies! Voices from a Medieval Village by Laura Amy Schlitz JUV 812.6 SCH 2007: The Higher Power of Lucky by Susan Patron, illus. by Matt Phelan JUV PAT 2006: Criss Cross by Lynne Rae Perkins JUV PER 2005: Kira-Kira by Cynthia Kadohata JUV KAD 2004: The Tale of Despereaux by Kate DiCamillo JUV DIC 2003: Crispin: The Cross of Lead by Avi JUV AVI 2002: A Single Shard by Linda Sue Park JUV PAR 2001: A Year Down Yonder by Richard Peck JUV PEC 2000: Bud, Not Buddy by Christopher Paul Curtis JUV CUR 1999: Holes by Louis Sachar JUV SAC 1998: Out of the Dust by Karen Hesse JUV HES 1997: The View from Saturday by E.L. Konigsburg JUV KON 1996: The Midwife's Apprentice by Karen Cushman JUV CUS 1995: Walk Two Moons by Sharon Creech JUV CRE 1994: The Giver by Lois Lowry JUV LOW 1993: Missing May by Cynthia Rylant JUV RYL 1992: Shiloh by Phyllis Reynolds Naylor JUV NAY 1991: Maniac Magee by Jerry Spinelli JUV SPI 1990: Number the Stars by Lois Lowry JUV LOW 1989: Joyful Noise: Poems for Two Voices by Paul Fleischman JUV 811.54 FLE 1988: Lincoln: A Photobiography by Russell Freedman JUV 921 LIN FRE 1987: The Whipping Boy by Sid Fleischman JUV FLE 1986: Sarah, Plain and Tall by Patricia MacLachlan JUV MAC 1985: The Hero and the Crown by Robin McKinley JUV MCK 1984: Dear Mr.