Bill Fraser’S War Diary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DESERT KNIGHTS the Birth and Early History Of

DESERT KNIGHTS The birth and early history of the SAS by Stephen Gallagher 2x90’ Part One Dr3 Gallagher/DESERT KNIGHTS1/1 1. EXT. KEIR HOUSE, SCOTLAND. NIGHT. We see a large, white country house in formal grounds, lights blazing from the ground floor windows. We can hear a faint buzz of dinner conversation. Over the building we super: KEIR HOUSE, SCOTLAND 2. INT. KEIR HOUSE DINING ROOM. NIGHT. A formal dinner party in full swing, sometime around the late 1920s. The women are in gowns and many of the men are in kilts and medals. 3. INT. KEIR HOUSE UPPER FLOOR. NIGHT. An empty, unlit corridor. Not lavish, but functional. A BAR OF LIGHT showing under a door. It goes out. PAN UP as the door opens a crack and DAVID checks the corridor before emerging. He's a dark-haired boy of about 12, with a dressing-gown over his pyjamas. 4. INT. KEIR HOUSE HALLWAY. NIGHT. Up at the top of the stairs, DAVID's head cautiously pokes into view. HIS POV down on the dining room doors as the butler goes in and closes them after... from the sound that's coming out they seem to be making speeches, and there's a burst of applause. Warily, he makes his way down. At the foot of the stairs, he tiptoes past the dining room. But just as it looks as if he's in the clear, he hears someone coming. He dives into the nearest cover just as... ALICE THE COOK emerges through a door from the kitchens with one of the MAIDS behind her. -

USAMHI Special Forces

U.S. Army Military History Institute Special Operations 950 Soldiers Drive Carlisle Barracks, PA 17013-5021 15 Jun 2012 FOREIGN SPECIAL FORCES A Working Bibliography of MHI Sources CONTENTS Soviet.....p.1 British.....p.2 Other…..p.3 SOVIET SPECIAL FORCES Adams, James. Secret Armies: Inside the American, Soviet and European Special Forces. NY: Atlantic Monthly, 1988. 440 p. UA15.5.A33. Amundsen, Kirsten, et. al. Inside Spetsnaz: Soviet Special Operations: A Critical Analysis. Novato, CA: Presidio, 1990. 308 p. UZ776.S64.I57. Boyd, Robert S. "Spetznaz: Soviet Innovation in Special Forces." Air University Review (Nov/Dec 1986): pp. 63-69. Per. Collins, John M. Green Berets, Seals and Spetznaz: U.S. and Soviet Special Military Operations. Wash, DC: Pergamon-Brassey's, 1987. 174 p. UA15.5.C64. Gebhardt, James F. Soviet Naval Special Purpose Forces: Origins and Operations in World War II. Ft Leavenworth: SASO, 1989. 41 p. D779.R9.G42. _____. Soviet Special Purpose Forces: An Annotated Bibliography. Ft. Leavenworth, KS: SASO, 1990. 23 p. Z672.4S73.G42. Kohler, David R. "Spetznaz (Soviet Special Purpose Forces)." US Naval Institute Proceedings (Aug 87): pp. 46-55. Per. Resistance Factors and Special Forces Areas, North European Russia…. Wash, DC: Asst Chief of Staff, Intell, 1957. 387 p. DK54.R47. Suvorov, Viktor. Spetsnaz: The Inside Story of the Soviet Special Forces. NY: Pocketbooks, 1990. 244 p. UA776.S64.S8813. Zaloga, Steve. Inside the Blue Berets: A Combat History of Soviet and Russian Airborne Forces, 1930- 1995. Novato, CA: Presidio, 1995. 339 p. UZ776S64.Z35. _____. Soviet Bloc Elite Forces. London: Osprey, 1985. -

An Analysis of the New Zealand Contribution to the Long Range Desert Group in North Africa, 1940-1943

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. ' 1 Raids, Road Watches, and Reconnaissance. An Analysis of the New Zealand Contribution to the Long Range Desert Group in North Africa, 1940-1943 A Thesis presented in partial fu lfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Hi story at the School of History, Philosophy and Politics - Massey University By Clive Gower-Collins 1999 I Table of Contents Contents..................... ........................................ ...................... I Acknowledgements . II List of Illustrations . III Introduction . .. .. .. 1 Chapter One - Background and Conception . 5 Chapter Two - Serving Two Masters . 14 Chapter Three - Raids . 30 Chapter Four - Road Watches......... ................ ............................. 49 Chapter Five - Reconnaissance . .. .. .... 61 Conclusion . 78 Bibliography . .. ... 81 C Gower-Collins 1999 II Acknowledgements I have been the fortunate recipient of considerable assistance m the course of completing this thesis. I wish to thank my supervisor, Dr James Watson for his efforts on my behalf, and both the administrative and academic staff of the department for their assistance and encouragement. My thanks also go to Professor David Thomson for the benefit of his counsel. I also want to recognise Massey University for its generous award of scholarships in both 1998 and 1999, without which I would have been able to continue my research. I am indebted to the following people and organisations for their assistance: Esther Bullen, The New Zealand Educational Review. Mr Merv Curtis, LRDG. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

SOE) by Donat Gallagher James Cook University

EVELYN WAUGH STUDIES Vol. 43, No. 2 Autumn 2012 Captain Evelyn Waugh and the Special Operations Executive (SOE) by Donat Gallagher James Cook University “There was something in him . of the sort of subaltern who was disliked in his regiment and got himself posted to S.O.E.”[1] Early in the Second War the British Government set up a highly secret Special Operations Executive (SOE). Its many tasks included sabotage, espionage, and aiding resistance movements in nations occupied by the Axis; in Winston Churchill’s words, its mission was “to set Europe ablaze.” It had many auxiliary units, one of which might interest United States readers while suggesting the flavour of the organization. This was British Security Coordination (BSC) in the Rockefeller Center in New York, whose history (unlike that of most other such units) survived shredding through the enterprise of some of its members. Led by a Canadian tycoon, William Stephenson, its brief from Churchill was to “do all that was not being done and could not be done by overt means” to “drag America into the war.” Before Pearl Harbour, BSC sabotaged United States firms dealing with Germany and undermined isolationist groups like America First and the pro-Nazi Bund. This they did by blackmail and assassination and by running a “rumour mill” against opponents of the war with information obtained from wire taps and burgled safes. They also bought a news agency to plant untrue stories in obscure papers; friendly columnists like Walter Winchell and Drew Pearson then picked them up. BSC faked incidents to influence American public opinion, the most famous being the forging and planting of a “secret Nazi map” and the “Belmonte letter.” The “secret map” showed South America divided into five Nazi states, one of which included the Panama Canal, while the “Belmonte letter” outlined a Nazi plot to overthrow the Bolivian Government. -

The Ampleforth Journal

The Ampleforth Journal September 2017 - December 2018 Volume 122 4 THE AMPLEFORTH JOURNAL VOL 122 ConTenTS eDiToriAl 6 The Abbey The Ampleforth Community 7 on the holy Father’s Call to holiness in Today’s World 10 Volunteering for the Mountains of the Moon 17 everest May 2018 25 Time is running out 35 What is the life of a Christian in a large corporation? 40 The british officer and the benedictine Tradition 45 A Chronicle of the McCann Family 52 The Silent Sentence 55 Joseph Pike: A happy Catholic Artist 57 Fr Theodore young oSb 62 Fr Francis Dobson oSb 70 Fr Francis Davidson oSb 76 Abbot Timothy Wright oSb 79 Prior Timothy horner oSb 85 Maire Channer 89 olD AMPleForDiAnS The Ampleforth Society 90 old Amplefordian obituaries 93 AMPleForTh College headmaster’s exhibition Speech 127 into the Woods 131 ST MArTin’S AMPleForTh Prizegiving Speech 133 The School 140 CONTENTS 5 eDiToriAl Fr riChArD FFielD oSb eDiTor oF The AMPleForTh JournAl The recent publicity surrounding the publishing of the iiCSA report in August may have awakened unwelcome memories among those who have suffered at the hands of some of our brethren. We still want to reach out to them and the means for this are still on the Ampleforth Abbey website under the safeguarding tab. it has been encouraging to us to receive so many messages of support and to know that no parents saw fit to remove their children from our schools. And there is increasing interest from all sorts of people in the retreats run here throughout the year by different monks, together with requests for monks to go and speak or preach at different venues and events. -

DEATH of a BATTLESHIP the LOSS of HMS PRINCE of WALES December 10, 1941

DEATH OF A BATTLESHIP THE LOSS OF HMS PRINCE OF WALES December 10, 1941 A Marine Forensics Analysis of the Sinking Garzke - Dulin - Denlay Table of Contents Introduction to the 2010 Revision................................................................................................... 3 Abstract........................................................................................................................................... 5 Historical Background.................................................................................................................... 6 Force Z Track Chart.................................................................................................................. 11 The Fatal Torpedo Hit .................................................................................................................. 13 Figure 1 – Location of the First Torpedo Hit............................................................................ 15 Figure 2 – Transverse Section...................................................................................................18 Figure 3 – Arrangement of Port Outboard Shaft Tunnel .......................................................... 20 Figure 4 – Flooding Diagrams after First Torpedo Hit............................................................. 22 Figure 4a – Machinery and Magazine Arrangements Schematic ............................................. 22 Figure 4b – Location of the Port Torpedo Hit ......................................................................... -

The London of TUESDAY, the Zgth of JULY, 1947 by Finfyotity Registered As a Newspaper THURSDAY, 31 JULY, 1947 BATTLE of MATAPAN

(ftumb. 38031 3591 THIRD SUPPLEMENT TO The London Of TUESDAY, the zgth of JULY, 1947 by finfyotity Registered as a newspaper THURSDAY, 31 JULY, 1947 BATTLE OF MATAPAN. 4. The disposition originally ordered left the The following Despatch was submitted to the cruisers without support. The battlefleet could Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty on the if necessary have put to sea, but very nth November, 1941, by Admiral Sir inadequately screened. Further consideration Andrew B. Cunningham, G.C.B., D.S.O., led to the retention of sufficient destroyers to Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean Station. screen the battlefieet. The moment was a lucky one when more destroyers than usual Mediterranean, were at Alexandria having just returned from ntffe November,. 1941. or just awaiting escort duty. Be pleased to lay before Their Lordships the 5. It had already been decided to take the attached reports of the Battle of Matapan, 27th- battlefleet to sea under cover of night on the 30th March, 1941. Five ships of the enemy evening of the 27th, when air reconnaissance fleet were sunk, burned or destroyed as per from Malta reported enemy cruisers steaming margin.* Except for the loss of one aircraft eastward p.m./27th. The battlefleet accordingly in action, our fleet suffered no damage or proceeded with all possible secrecy. It was casualties. well that it did so, for the forenoon of the 28th 2. The events and information prior to the found the enemy south of Gavdo and the Vice- action, on which my appreciation was based, Admiral, Light Forces (Vice-Admiral H. -

Malayan Campaign 1941-42 Lessons for ONE SAF

POINTER MONOGRAPH NO. 6 Malayan Campaign 1941-42 Lessons for ONE SAF Brian P. Farrell ■ Lim Choo Hoon ■ Gurbachan Singh ■ Wong Chee Wai EDITORIAL BOARD Advisor BG Jimmy Tan Chairman COL Chan Wing Kai Members COL Tan Swee Bock COL Harris Chan COL Yong Wui Chiang LTC Irvin Lim LTC Manmohan Singh LTC Tay Chee Bin MR Wong Chee Wai MR Kuldip Singh A/P Aaron Chia MR Tem Th iam Hoe SWO Francis Ng Assistant Editor MR Sim Li Kwang Published by POINTER: Journal of the Singapore Armed Forces SAFTI MI 500 Upper Jurong Road Singapore 638364 website: www.mindef.gov.sg/safti/pointer First published in 2008 Copyright © 2008 by the Government of the Republic of Singapore. All right reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Ministry of Defence. Body text set in 12.5/14.5 point Garamond Book Produced by touche design CONTENTS About the Authors iv Foreword viii Chapter 1 1 Th e British Defence of Singapore in the Second World War: Implications for the SAF Associate Professor Brian P. Farrell Chapter 2 13 Operational Art in the Malayan Campaign LTC(NS) Gurbachan Singh Chapter 3 30 Joint Operations in the Malayan Campaign Dr Lim Choo Hoon Chapter 4 45 Command & Control in the Malayan Campaign: Implications for the SAF Mr Wong Chee Wai Appendices 62 ABOUT THE AUTHORS ASSOC PROF BRIAN P. FARRELL is the Deputy Head of the Dept. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Commando Country Special training centres in the Scottish highlands, 1940-45. Stuart Allan PhD (by Research Publications) The University of Edinburgh 2011 This review and the associated published work submitted (S. Allan, 2007. Commando Country. Edinburgh: NMS Enterprises Publishing) have been composed by me, are my own work, and have not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. Stuart Allan 11 April 2011 2 CONTENTS Abstract 4 Critical review Background to the research 5 Historiography 9 Research strategy and fieldwork 25 Sources and interpretation 31 The Scottish perspective 42 Impact 52 Bibliography 56 Appendix: Commando Country bibliography 65 3 Abstract S. Allan, 2007. Commando Country. Edinburgh: NMS Enterprises Publishing. Commando Country assesses the nature of more than 30 special training centres that operated in the Scottish highlands between 1940 and 1945, in order to explore the origins, evolution and culture of British special service training during the Second World War. -

Inclusive Dates: 1918-1966 Restrictions: Collection

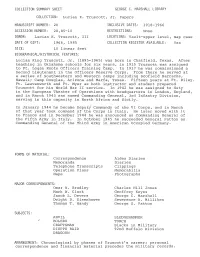

COLLECTION SUMMARY SHEET GEORGE C. MARSHALL LIBRARY COLLECTION: Lucian K. Truscott, Jr. Papers MANUSCRIPT NUMBER: 20 INCLUSIVE DATES: 1918-1966 ACCESSION NUMBER: 20,85-10 RESTRICTIONS: None DONOR: Lucian K. Truscott, III LOCATIONS: Vault-upper level, map case DATE OF GIFT: 1966, 1985 COLLECTION REGISTER AVAILABLE: Yes SIZE: 10 linear feet BIOGRAPHICAL/HISTORICAL FEATURES: Lucian King Truscott, Jr. (1895-1965) was born in Chatfield, Texas. After teaching in Oklahoma schools for six years, in 1915 Truscott was assigned to Ft. Logan Roots Officers Training Camp. In 1917 he was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the Officers Reserve Corps. From there he served at a series of Southwestern and Western camps including Scofield Barracks, Hawaii; Camp Douglas, Arizona and Marfa, Texas. Fifteen years at Ft. Riley. Ft. Leavenworth and Ft. Myer as both iI1;structor and student prepared Truscott for his World War II service. In 1942 he was assigned to duty in the European Theater of Operations with headquarters in London, England, and in March 1943 was named Commanding General, 3rd Infantry Division, serving in this capacity in North Africa and Sicily. " I In January 1944 he became Deputy Commandy of the VI Corps, and in March of that year took command of the Corps in Italy. He later moved with it to France and in December 1944 he was announced as Commanding General of the Fifth Army in Italy. In October 1945 he succeeded General Patton as Commanding General of the Third Army in American Occupied Germany. FORMS OF MATERIAL: Correspondence Aides Diaries Memoranda Diaries Telephone Transcripts Clippings Operation Plans Memorabilia lvlaps Photographs MAJOR CORRESPONDENTS: Omar N. -

Download Catalogue 31

WORLD WAR BOOKS Oaklands, Camden Park, Tunbridge Wells, Kent, England. TN2 5AE Tel / Fax 01892 538465 Email [email protected] TERMS OF BUSINESS The items in this catalogue are in net sterling prices. Postage and insurance are additional. If overseas customers wish to use airmail then please advise. The goods remain the property of World War Books until full payment has been received. PAYMENT Post and packing will be quoted at the time of order. For new or overseas customers payment will be required prior to despatch of books. For existing customers invoices are payable on receipt of books. Payment from abroad should be by sterling cheque drawn on UK bank, sterling bankers draft, or payment direct into our bank account using BIC. We are also pleased to take VISA or MASTERCARD in payment. WANTS LIST We make every effort to help customers find the book they require and are happy to add wants lists to our files. PURCHASE OF BOOKS AND EPHEMERA We are very keen to purchase good quality books and particularly ephemera including photo albums, scrapbooks, manuscripts, trench maps. We are always interested in any quantity, single items or collections and will travel anywhere to view and collect, if necessary. WORLD WAR BOOKS Catalogue 31 CONTENTS Items DIARIES, BOUND REPORTS, PHOTOGRAPH ALBUM, 1 - 43 EPHEMERA TRENCH MAPS 44 - 49 WORLD WAR ONE, INCLUDING REGIMENTAL 50 - 100 HISTORIES BOOKS FROM THE LIBRARY OF THE LATE ADMIRAL 101 - 152 & LADY KEYES & LORD ROGER KEYES WORLD WAR TWO (INCLUDING REGIMENTAL 153 - 166 HISTORIES ETC.) MANUALS (ARTILLERY, MACHINE GUN, MORTARS, 167 - 183 AMMUNITION MANUALS ETC.