Incongruence in the Historical Memory of Thomas Jefferson, 1936-1943

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Collect Coins a Fun, Useful, and Educational Guide to the Hobby

$4.95 Valuable Tips & Information! LITTLETON’S HOW TO CCOLLECTOLLECT CCOINSOINS ✓ Find the answers to the top 8 questions about coins! ✓ Are there any U.S. coin types you’ve never heard of? ✓ Learn about grading coins! ✓ Expand your coin collecting knowledge! ✓ Keep your coins in the best condition! ✓ Learn all about the different U.S. Mints and mint marks! WELCOME… Dear Collector, Coins reflect the culture and the times in which they were produced, and U.S. coins tell the story of America in a way that no other artifact can. Why? Because they have been used since the nation’s beginnings. Pathfinders and trendsetters – Benjamin Franklin, Robert E. Lee, Teddy Roosevelt, Marilyn Monroe – you, your parents and grandparents have all used coins. When you hold one in your hand, you’re holding a tangible link to the past. David M. Sundman, You can travel back to colonial America LCC President with a large cent, the Civil War with a two-cent piece, or to the beginning of America’s involvement in WWI with a Mercury dime. Every U.S. coin is an enduring legacy from our nation’s past! Have a plan for your collection When many collectors begin, they may want to collect everything, because all different coin types fascinate them. But, after gaining more knowledge and experience, they usually find that it’s good to have a plan and a focus for what they want to collect. Although there are various ways (pages 8 & 9 list a few), building a complete date and mint mark collection (such as Lincoln cents) is considered by many to be the ultimate achievement. -

Ft. Myers Rare Coins and Paper Money Auction (08/23/14) 8/23/2014 13% Buyer's Premium 3% Cash Discount AU3173 AB1389

Ft. Myers Rare Coins and Paper Money Auction (08/23/14) 8/23/2014 13% Buyer's Premium 3% Cash Discount AU3173 AB1389 www.gulfcoastcoin.com LOT # LOT # 400 1915S Pan-Pac Half Dollar PCGS MS67 CAC Old Holder 400r 1925 Stone Mountain Half Dollar NGC AU 58 1915 S Panama-Pacific Exposition 1925 Stone Mountain Memorial Half Dollar Commemorative Half Dollar PCGS MS 67 Old NGC AU 58 Holder with CAC Sticker - Toned with Min. - Max. Retail 55.00 - 65.00 Reserve 45.00 Beautiful Colors Min. - Max. Retail 19,000.00 - 21,000.00 Reserve 17,000.00 400t 1925 S California Half Dollar NGC MS 63 1925 S California Diamond Jubilee Half Dollar NGC MS 63 400c 1918 Lincoln Half Dollar NGC MS 64 Min. - Max. Retail 215.00 - 235.00 Reserve 1918 Lincoln Centennial Half Dollar NGC MS 190.00 64 Min. - Max. Retail 170.00 - 185.00 Reserve 150.00 401 1928 Hawaii Half Dollar NGC AU 58 1928 Hawaiian Sesquicentennial Half Dollar NGC AU 58 400e 1920 Pilgrim Half Dollar NGC AU 58 Min. - Max. Retail 1,700.00 - 2,000.00 Reserve 1920 Pilgrim Tercentenary Half Dollar NGC 1,500.00 AU 58 Min. - Max. Retail 68.00 - 75.00 Reserve 55.00 401a 1928 Hawaiian Half Dollar PCGS MS 65 CAC 1928 Hawaiian Sesquicentennial 400g 1921 Alabama Half Dollar NGC MS 62 Commemorative Half Dollar PCGS MS 65 with 1921 Alabama Centennial Commemorative Half CAC Sticker Dollar NGC MS 62 Min. - Max. Retail 4,800.00 - 5,200.00 Reserve Min. - Max. -

F. D. Roosevelt, Norman Rockwell & the Four Freedoms (1943)

F. D. Roosevelt, Norman Rockwell & the Four Freedoms (1943) Excerpt from Roosevelt’s January 16, 1941 speech before the U.S. Congress: “In the future days which we seek to make secure, we look forward to a world founded upon four essential human freedoms. The first is freedom of speech and expression -- everywhere in the world. The second is freedom of every person to worship God in his own way -- everywhere in the world. The third is freedom from want -- which, translated into world terms, means economic understandings which will secure to every nation a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants -- everywhere in the world. The fourth is freedom from fear -- which, translated into world terms, means a world-wide reduction of armaments to such a point and in such a thorough fashion that no nation will be in a position to commit an act of physical aggression against any neighbor-- anywhere in the world. That is no vision of a distant millennium. It is a definite basis for a kind of world attainable in our own time and generation. That kind of world is the very antithesis of the so-called new order of tyranny which the dictators seek to create with the crash of a bomb. To that new order we oppose the greater conception -- the moral order. A good society is able to face schemes of world domination and foreign revolutions alike without fear. Since the beginning of our American history, we have been engaged in change -- in a perpetual peaceful revolution -- a revolution which goes on steadily, quietly adjusting itself to changing conditions -- without the concentration camp or the quick-lime in the ditch. -

Margaret C. Rung Professor of History Director, History Program and Center for New Deal Studies Roosevelt University

Margaret C. Rung Professor of History Director, History Program and Center for New Deal Studies Roosevelt University 430 S. Michigan Ave., Chicago, Illinois 60605 (w) 312-341-3724, Rm 834 e-mail: [email protected] Education: Ph.D., The Johns Hopkins University (History) M.A., The Johns Hopkins University (History) B.A., Oberlin College (Phi Beta Kappa) Professional Positions: Professor of History, Roosevelt University Chair, Department of History and Philosophy, 2013-2017 Director of the Center for New Deal Studies, Roosevelt University 2002- Associate Dean, College of Arts & Sciences, Roosevelt University, 2001-2005 Program Coordinator, History, 1999-2000, 2001-2005 Visiting Fulbright Lecturer, University of Latvia, Riga, Latvia, 2000-2001 Assistant Professor of History, Mount Allison University, 1993-1994 Research/Professional Experience: Research & Editorial Assistant, The Dwight David Eisenhower Papers Project, Baltimore, Maryland, 1987-1993 Research Historian, History Associates, Inc., Rockville, Maryland, 1985-1990 *Significant projects: Rung, "Celebrating One Hundred Years: A History of Florida National Bank." Recipient of Golden Image Award, Florida Public Relations Association, April 1988. *Research assistance on: Richard G. Hewlett, Jessie Ball DuPont. Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1992; Rodney P. Carlisle, Where the Fleet Begins: A History of the David Taylor Naval Research Center, 1898-1998. Washington, D.C.: Naval Historical Center, 1998; Dian O.Belanger, Managing American Wildlife: A History of the International Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies. Amherst: University of Massachusetts, 1988. Archival Assistant, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Washington, D.C., 1985 Publications: With Erik Gellman, “The Great Depression” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of American History, ed. Jon Butler. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018. -

A Measure of Detachment: Richard Hofstadter and the Progressive Historians

A MEASURE OF DETACHMENT: RICHARD HOFSTADTER AND THE PROGRESSIVE HISTORIANS A Thesis Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS By Wiliiam McGeehan May 2018 Thesis Approvals: Harvey Neptune, Department of History Andrew Isenberg, Department of History ABSTRACT This thesis argues that Richard Hofstadter's innovations in historical method arose as a critical response to the Progressive historians, particularly to Charles Beard. Hofstadter's first two books were demonstrations of the inadequacy of Progressive methodology, while his third book (the Age of Reform) showed the potential of his new way of writing history. i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................i CHAPTER 1. A MEASURE OF DETACHMENT..........................................................................1 2. SOCIAL DARWINISM IN AMERICAN THOUGHT………………………………………………26 3. THE AMERICAN POLITICAL TRADITION…………………………………………………………..52 4. THE AGE OF REFORM…………………………………………………………………………………….100 5. CONCLUSION…………………………………………………………………………………………………139 BIBLIOGRAPHY…………………………………………………………………………………………………………..144 CHAPTER ONE A MEASURE OF DETACHMENT Great thinkers often spend their early years in rebellion against the teachers from whom they have learned the most. Freud would say they live out a form of the Oedipal archetype, that son must murder his father at least a little bit if he is ever to become his own man. -

The Thomas Jefferson Memorial, Washington

JL, JLornclt ),//,.,on Wn*ooio/ memorial ACTION PUBLICATIONS Alexandria, Va. JL" llo*oo )"ff",.", TLln^o,io/ This great National Memorial to the aurhor of the Declaration of Indepen- dence and the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, First Secretary of State and Third President of the United States, possesses mlny of the qualities ascribed to the brilliant revolutionary leader in whose memory it has been dedicated by a grateful Nation It is magnificent-as Jefferson's chrracter was magnificent. Simple as his Democracy. Aesthetic as l.ris thoughts. Courageous as his chempion- ship of the righrs of man. The memorial structure is in itself a tribute to Jefferson's artistic tastes and preference and a mark of respect for his architectural and scientific achievements. A farmer by choice, a lawyer by profession, and an architect by avocation, JelTer- son \r,as awed by the remarkable beauty of design and noble proportions of the Pantheon in Rome and foilou,ed irs scheme in the major architectururl accom- plishments of his oq,n life Its inlluence is evident in his ovu'n home at Monticello and in the Rotunda of the University of Virginia at Cl.rarkrttesville, which he designed. The monumental portico complimenrs Jellerson's design for the Yir- ginia State Capitol at Richmond. h But it is not alone the architectural splendor or the beiruty of its settir,g ',irhich makes this memcrial one of the mosr revered American patriotic shrines. In it the American people find the spirit of the living Jefferson and the fervor which inspired their colonial forbears to break, by force of erms, the ties which bound them to tyrannical overlords; to achieve not only nltional independence. -

REVISITING the FOUR FREEDOMS by Donald M

EXCLUSIVE MCUF FEATURE REVISITING THE FOUR FREEDOMS By Donald M. Bishop PHOTO: The Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park, located on an island in New York's East River, opened in 2012 3 • MARINE CORPS UNIVERSITY FOUNDATION • SUMMER 2019 EXCLUSIVE MCUF FEATURE Modern political warfare now includes both cyber and information operations. At MCU, Bren Chair of Strategic Communications Donald Bishop focuses his teaching and presentations on the “information” or “influence” dimension of conflict – disinformation, propaganda, persuasion, hybrid warfare – now enabled by the internet and social media. And he emphasizes that Americans, as they confront violent extremism and other threats, must know and be confident of the American values they defend. "Thanks, Grandpa, for coming to my game." Why look back at The Four Freedoms? First, in my classes at Marine Corps University, I’ve discovered that the current "I enjoyed it too, Jack. We men in our eighties don't get generation of Marines have never heard of them. Of Norman out as often as we wish. Seeing you score a run was Rockwell’s four famous paintings, they have seen only one – something. But you know, I noticed something else today. the family at Thanksgiving – and they don’t know they were "When you were at the plate, it carried me back to part of a series. Second – when Americans must articulate watching my older brother in the batter's box. You held the “what we’re for” (rather than “what we’re against”) – whether bat like he did. You have the same stance and the same in the war on terrorism or in a future of great power competi- swing. -

October 5, 2019

THE FOUR FREEDOMS AWARDS THE ROOSEVELT INSTITUTE The Four Freedoms Awards are presented to individuals and organizations whose Presents achievements have demonstrated a commitment to the principles which President Roosevelt proclaimed in his historic speech to Congress on January 6, 1941, as essential to democracy: freedom of speech and expression, freedom of worship, freedom from want, freedom from fear. The Roosevelt Institute has awarded the Four Freedoms Medals to some of the most distinguished Americans and world citizens of our time, including Presidents Truman, Carter, and Clinton; Nelson Mandela; Coretta Scott King; Arthur Miller; Desmond Tutu; and the Honorable Ruth Bader Ginsburg. The Four Freedoms Awards are presented in alternating years by the Roosevelt Institute in the U.S. and Roosevelt Stichting in the Netherlands. We are honored to host a delegation of guests from the Netherlands in Hyde Park for the 2019 awards. THE ROOSEVELT INSTITUTE Until economic and social rules work for all Americans, they’re not working. Inspired by the legacy of Franklin and Eleanor, the Roosevelt Institute reimagines the rules to create a nation where everyone enjoys a fair share of our collective prosperity. OCTOBER 5, 2019 We are a 21st century think tank, bringing together multiple generations of thinkers and leaders to help drive key economic and social debates and have local and national impact. The Roosevelt Institute is also the nonprofit partner to the FDR Presidential Library and Museum. THE FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM The Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum is America’s first presidential library—and the only one used by a sitting president. -

Under the Direction of Professor David A

ABSTRACT MEDLIN, ERIC PATRICK. The Historian and the Liberal Intellectual: Power and Postwar American Historians, 1948-1975. (Under the direction of Professor David A. Zonderman.) Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., Richard Hofstadter, and Daniel Boorstin were three of the most influential American historians of the post-World War II period. They sold millions of books, influenced historiographic debates, and filled prominent positions in society and government. Schlesinger spent two years as a special adviser to President Kennedy, Hofstadter served on the board of the forerunner to PBS, and Boorstin became the first historian to be appointed Librarian of Congress. Over the past five decades, historians have characterized these writers as conservative academics who focused on consensus and agreement in American history. My work challenges that notion. In this thesis, I analyze the writings, speeches, and personal correspondence of Schlesinger, Hofstadter, and Boorstin between 1945 and 1975. My study focuses on both their political ideas and their roles in society. I look at how their work articulated different arguments for and ideas about liberalism during this period. I argue that their positions and roles in society changed in response to their ideas about what society needed from intellectuals. I also argue that the experiences and successes of these figures a provide a template for contemporary public intellectuals who desire both academic and public relevance. © Copyright 2017 by Eric Patrick Medlin All Rights Reserved The Historian and the Liberal Intellectual: Power and Postwar American Historians, 1948-1975 by Eric Patrick Medlin A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of North Carolina State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts History Raleigh, North Carolina 2017 APPROVED BY: ____________________________ ____________________________ Julia E. -

Is Over – Now What? Restoring the Four Freedoms As a Foundation for Peace and Security

The “War on Terror” Is Over – Now What? Restoring the Four Freedoms as a Foundation for Peace and Security Mark R. Shulman* As for our common defense, we reject as false the choice between our safety and our ideals. Our founding fathers, faced with perils that we can scarcely imagine, drafted a charter to assure the rule of law and the rights of man, a charter expanded by the blood of generations. Those ideals still light the world, and we will not give them up for expedience’s sake. And so, to all other peoples and governments who are watching today, from the grandest capitals to the small village where my father was born: know that America is a friend of each nation and every man, woman and child who seeks a future of peace and dignity, and we are ready to lead once more. – Barack H. Obama Inaugural Address, Jan. 20, 20091 The so-called “war on terror” has ended.2 By the end of his first week in office, President Barack H. Obama had begun the process of dismantling some of the most notorious “wartime” measures.3 A few weeks before, recently reappointed Secretary of Defense Robert M. Gates had clearly forsaken the contentious label in a post-election essay on U.S. strategy in Foreign Affairs.4 Gates noted this historic shift in an almost offhanded * Assistant Dean for Graduate Programs and International Affairs and Adjunct Professor of Law at Pace University School of Law. A previous iteration of this article appeared in the Fordham Law Review. -

Read It Online

Serving the Numismatic Community Since 1959 Village Coin Shop Catalog 2020-2021 Vol. 59 www.villagecoin.com • P.O. Box 207 • Plaistow, NH 03865-0207 2020 U.S. Gold Eagles Half Dollar Commemoratives • Brilliant Uncirculated All in original box with COA unless noted **In Capsules Only • Call For Prices USGE1 . .1/10 oz Gold Eagle USGE2 . .1/4 oz Gold Eagle USGE3 . .1/2 oz Gold Eagle USGE4 . .1 oz Gold Eagle ITEM DESCRIPTION GRADE PRICE CMHD82B7 . .1982-D Washington . BU . $16 .00 Commemorative Sets CMHD82C8 . .1982-S Washington . Proof . 16 .50 CMHD86B7 . .1986-D Statue of Liberty** . BU . 5 .00 CMHD86C8 . .1986-S Statue of Liberty** . Proof . 4 .00 CMHD91C7 . .1991-D Mount Rushmore . BU . 20 .00 CMHD91C8 . .1991-S Mount Rushmore . Proof . 28 .00 CMHD92C8 . .1992-S Olympic . BU . 35 .00 CMHD92C8 . .1992-S Olympic . Proof . 35 .00 CMHD93D7 . .1993-W Bill of Rights . BU . 40 .00 CMHD93C8 . .1993-S Bill of Rights . Proof . 35 .00 CMHD93A7 . .1993-P World War II . BU . 30 .00 CMHD93A8 . .1993-P World War II . Proof . 36 .00 CMHD94B7 . .1994-D World Cup . BU . 13 .00 ITEM DESCRIPTION GRADE PRICE CMHD94A8 . .1994-P World Cup . Proof . 13 .00 Two-Coin Half Dollar And Silver Dollar Sets CMHD95A7 . .1995-P Civil War . BU . 63 .00 CMTC86A7 . .1986 Statue of Liberty . BU . $ 39 .00 CMHD95C9 . .1995-S Civil War . Proof . 63 .00 CMTC86A8 . .1986 Statue of Liberty . Proof . 39 .00 CMHD95C7 . .1995-S Olympic Basketball . BU . 27 .50 CMTC86C8 . .1989 Congressional . Proof . 49 .00 CMHD95C8 . .1995-S Olympic Basketball . Proof . 35 .00 CMHD95C7 . .1995-S Olympic Baseball . -

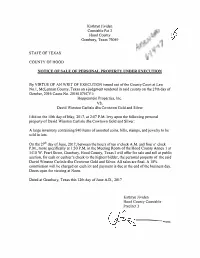

Notice of Sale of Personal Property Under Execution

Kathryn Jividen Constable Pct 3 Hood County Granbury, Texas 76049 STATE OF TEXAS COUNTY OF HOOD NOTICE OF SALE OF PERSONAL PROPERTY UNDER EXECUTION By VIRTUE OF AN WRIT OF EXECUTION issued out ofthe County Court at Law No. I, McLennan County, Texas on a judgmentrend ered in said county on the 27th day of October, 2016 Cause No. 20161075CVI: Hoppenstein Properties, Inc. vs. David Winston Carlisle dba Cowtown Gold and Silver I did on the 10th day of May, 2017, at 2:07 P.M. levy upon the following personal property of David Winston Carlisle dba Cowtown Gold and Silver: A large inventory containing 940 items of assortedcoins, bills, stamps, and jewelry to be sold in lots. On the 2th day of June, 2017, between the hours often o'clock A.M. and fouro' clock P.M., more specifically at I :30 P.M. in the Meeting Room of the Hood County Annex 1 at 1410 W. Pearl Street, Granbury, Hood County, Texas I will offer forsale and sell at public auction, for cash or cashier's check to the highest bidder, the personal propertyof the said David Winston Carlisle dba Cowtown Gold and Silver. All sales are final.A 10% commission will be charged on each lot and payment is due at the end of the business day. Doors open forviewing at Noon. Dated at Granbury, Texas this 12th day of June A.O., 2017 Kathryn Jividen Hood County Constable Precinct 3 --=-==--- Lot 1 Lot 4 #29, 43, 66, 69 Plastic Bin with Pennies The Complete Collection of uncirculated Sacagawea 293 .50cent rolls of pennies Golden Dollars PCS Stamps & Coins .41 cents loose pennies The Complete Collection