Indo-Iranian Vayu and Gogolean Viy: an Old Hypothesis Revisited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yoga and the Five Prana Vayus CONTENTS

Breath of Life Yoga and the Five Prana Vayus CONTENTS Prana Vayu: 4 The Breath of Vitality Apana Vayu: 9 The Anchoring Breath Samana Vayu: 14 The Breath of Balance Udana Vayu: 19 The Breath of Ascent Vyana Vayu: 24 The Breath of Integration By Sandra Anderson Yoga International senior editor Sandra Anderson is co-author of Yoga: Mastering the Basics and has taught yoga and meditation for over 25 years. Photography: Kathryn LeSoine, Model: Sandra Anderson; Wardrobe: Top by Zobha; Pant by Prana © 2011 Himalayan International Institute of Yoga Science and Philosophy of the U.S.A. All rights reserved. Reproduction or use of editorial or pictorial content in any manner without written permission is prohibited. Introduction t its heart, hatha yoga is more than just flexibility or strength in postures; it is the management of prana, the vital life force that animates all levels of being. Prana enables the body to move and the mind to think. It is the intelligence that coordinates our senses, and the perceptible manifestation of our higher selves. By becoming more attentive to prana—and enhancing and directing its flow through the Apractices of hatha yoga—we can invigorate the body and mind, develop an expanded inner awareness, and open the door to higher states of consciousness. The yoga tradition describes five movements or functions of prana known as the vayus (literally “winds”)—prana vayu (not to be confused with the undivided master prana), apana vayu, samana vayu, udana vayu, and vyana vayu. These five vayus govern different areas of the body and different physical and subtle activities. -

Yin-Yang, the Five Phases (Wu-Xing), and the Yijing 陰陽 / 五行 / 易經

Yin-yang, the Five Phases (wu-xing), and the Yijing 陰陽 / 五行 / 易經 In the Yijing, yang is represented by a solid line ( ) and yin by a broken line ( ); these are called the "Two Modes" (liang yi 兩義). The figure above depicts the yin-yang cycle mapped as a day. This can be divided into four stages, each corresponding to one of the "Four Images" (si xiang 四象) of the Yijing: 1. young yang (in this case midnight to 6 a.m.): unchanging yang 2. mature yang (6 a.m. to noon): changing yang 3. young yin (noon to 6 p.m.): unchanging yin 4. mature yin (6 p.m. to midnight): changing yin These four stages of changes in turn correspond to four of the Five Phases (wu xing), with the fifth one (earth) corresponding to the perfect balance of yin and yang: | yang | yin | | fire | water | Mature| |earth | | | wood | metal | Young | | | Combining the above two patterns yields the "generating cycle" (below left) of the Five Phases: Combining yin and yang in three-line diagrams yields the "Eight Trigrams" (ba gua 八卦) of the Yijing: Qian Dui Li Zhen Sun Kan Gen Kun (Heaven) (Lake) (Fire) (Thunder) (Wind) (Water) (Mountain) (Earth) 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 The Eight Trigrams can also be mapped against the yin-yang cycle, represented below as the famous Taiji (Supreme Polarity) Diagram (taijitu 太極圖): This also reflects a binary numbering system. If the solid (yang) line is assigned the value of 0 and the broken (yin) line is 1, the Eight Trigram can be arranged to represent the numbers 0 through 7. -

THEORY of AYURVEDA (An Overview)

THEORYTHEORY OFOF AYURVEDAAYURVEDA (An(An Overview)Overview) Dr Chakra Pany Sharma M. D. ( Ayu ), PhD ( Sch ) READER -PG MMM Govt Ayurveda College Udaipur -India Lord Brhama Lord Dhanvantari-The 313001 Father of Surgery Email: [email protected] [email protected] An Overview of Lake City Udaipur Fatehsagar Lake and Island Park Greenery in Rural Area Clouds over the Peak of Mountain Night Scenario of Fountain Park Introduction & Background Ayurveda (Devanagari : आयुवBद ) or Ayurvedic medicine is an ancient system of health care that is native to the Indian subcontinent . It is presently in daily use by millions of people in India , Nepal , Sri Lanka ,China , Tibet, and Pakistan . It is now in practice for health care in Europian countries. The word " Ayurveda " is a tatpurusha compound of the word āyus meaning "life" or "life principle", and the word veda , which refers to a system of "knowledge". Continued…………………….. According to Charaka Samhita , "life" itself is defined as the "combination of the body, sense organs, mind and soul, the factor responsible for preventing decay and death." According to this perspective, Ayurveda is concerned with measures to protect "ayus ", which includes healthy living along with therapeutic measures that relate to physical, mental, social and spiritual harmony. Continued…………………. Ayurvedavatarana (the "descent of Ayurveda ") Brahama Daksha Prajapati Indra Bharadwaj Bharadvaja in turn taught Ayurveda to a group of assembled sages, who then passed down different aspects of this knowledge to their students . Continued…………………. According to tradition, Ayurveda was first described in text form by Agnivesha , named - Agnivesh tantra . The book was later redacted by Charaka , and became known as the Charaka Samhit ā. -

Dead Souls Online

HI6qS (Online library) Dead Souls Online [HI6qS.ebook] Dead Souls Pdf Free Nikolai Gogol ebooks | Download PDF | *ePub | DOC | audiobook Gogol Nikolai 2016-06-21Original language:English 9.00 x .69 x 6.00l, .91 #File Name: 1534806385306 pagesDead Souls | File size: 73.Mb Nikolai Gogol : Dead Souls before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Dead Souls: 3 of 3 people found the following review helpful. one of the best examples of Russian literatureBy snoozerClassic story, one of the best examples of Russian literature, multilayered, funny, smart.4 of 4 people found the following review helpful. Greatly doneBy N. YablonkoGreat classic book. Actually, finally managed to read it till the end, mostly because of how it's easy to read and navigate. Definitely recommend this Kindle Edition and publisher. Since its publication in 1842, Dead Souls has been celebrated as a supremely realistic portrait of provincial Russian life and as a splendidly exaggerated tale; as a paean to the Russian spirit and as a remorseless satire of imperial Russian venality, vulgarity, and pomp. As Gogol's wily antihero, Chichikov, combs the back country wheeling and dealing for "dead souls"--deceased serfs who still represent money to anyone sharp enough to trade in them--we are introduced to a Dickensian cast of peasants, landowners, and conniving petty officials, few of whom can resist the seductive illogic of Chichikov's proposition. Dead Souls is unanimously considered one of the greatest novels in the Russian language for its characterizations, satiric humor, and style. -

Olga Zaitseva: Every Woman Is a Witch…

We have only fresh and savory news! December 2013 | № 12 (123) DO NOT MISS: December 8 – Korchma on Borovskoye Highway December 22 — Korchma in Sadovo-Samotochnaya Street December 29 — Korchma in Pyatnitskaya Street December 29 — Korchma in Bochkova Street More news and photos at www.tarasbulba.us e U v o [email protected] k l r a h Project manager – Yuri Beloyvan i it n [email protected] i w an e c ad uisine – m OLGA ZAITSEVA: EVERY WOMAN IS A WITCH… VIY: RETURNING PREMIERE 30 january in 3D INCREDIBLE ASIA: Blood, sacrifices and cremation in Nepal THE NEW YEAR: tar barrels, flower offerings and mass spam DELIVERY OF HOMEMADE UKRAINIAN FOOD AND HOTLINE 6+ www.tarasbulba.us (212) 510-75-10 2 | GUEST SHE BROUGHT TOGETHER THE OPPOSITE FEATURES OF A BEAUTY AND A WICKED WITCH IN THE ROLE OF GOGOL’S PANNOCHKA FROM THE HORROR STORY VIY, IN SEARCH OF THE BEST ANGLE SHE COULD LIE IN A COFFIN FOR HOURS … SHE WAS CHOSEN FOR THE PART FROM AMONG THOUSANDS OF CANDIDATES AND THE RESULT SURPASSED ALL EXPECTATIONS… THE NEW 3D VERSION OF VIY COMES TO THEATERS ON JANUARY 30; MEANWHILE BULBA NEWS TALKED TO OLGA ZAYTSEVA WHO PORTRAYED THE LEGENDARY PANNOCHKA IN THE MOVIE. OLGA ZAITSEVA: “EVERY WOMAN IS A WITCH…” – Olga, how did you start your work with the film creators? What is your secret? – It’s not a secret, really. We have been working together for long time, and working well. It all started at casting, like with all actors. I came in, and what followed next was ridiculous. -

A Brief Mention of Agni in Brihatrayee

ISSN 2664-3987 (Print) & ISSN 2664-6722 (Online) South Asian Research Journal of Medical Sciences Abbreviated Key Title: South Asian Res J Med Sci | Volume-1 | Issue-1| Jun-Jul -2019 | Review Article A Brief Mention of Agni in Brihatrayee Dr. Chumi Bhatta1*, Dr. Khagen Basumatary2 1P.G Scholar, Department of Samhita and Siddhanta, Government Ayurvedic college, Jalukbari-14, Assam, India 2Professor and HOD, Department of Samhita and Siddhanta, Government Ayurvedic college, Jalukbari-14, Assam, India *Corresponding Author Dr. Chumi Bhatta Article History Received: 21.06.2019 Accepted: 12.07.2019 Published: 30.07.2019 Abstract: The primary aim and objective of Ayurveda is to maintain the health of healthy person and to eradicate the diseases of a diseased person is the secondary one. One whose dosa, agni, dhatu and malas are in balanced state and whose senses, mind and soul are functioning properly is a healthy individual. Agni maintains the physiology of this deha desha. In other words agni controls the state of biological equilibrium of dosha, dhatu and mala. The derangement of agni produces various diseases and it is the root cause of all diseases. In Ayurveda the term agni is used in the sense of digestion of food and metabolic products.Agni converts food in the form of energy, which is responsible for all the vital functions of our body. So it is necessary to know all the reference found in brihatrayee. Keywords: ayurveda, agni, dosha, dhatu, mala INTRODUCTION The Ayurvedic concept of agni is critically important to our overall health. Agni is the force of intelligence within each cell, each tissue and every system within the body. -

Vishvarupadarsana Yoga (Vision of the Divine Cosmic Form)

Vishvarupadarsana Yoga (Vision of the Divine Cosmic form) 55 Verses Index S. No. Title Page No. 1. Introduction 1 2. Verse 1 5 3. Verse 2 15 4. Verse 3 19 5. Verse 4 22 6. Verse 6 28 7. Verse 7 31 8. Verse 8 33 9. Verse 9 34 10. Verse 10 36 11. Verse 11 40 12. Verse 12 42 13. Verse 13 43 14. Verse 14 45 15. Verse 15 47 16. Verse 16 50 17. Verse 17 53 18. Verse 18 58 19. Verse 19 68 S. No. Title Page No. 20. Verse 20 72 21. Verse 21 79 22. Verse 22 81 23. Verse 23 84 24. Verse 24 87 25. Verse 25 89 26. Verse 26 93 27. Verse 27 95 28. Verse 28 & 29 97 29. Verse 30 102 30. Verse 31 106 31. Verse 32 112 32. Verse 33 116 33. Verse 34 120 34. Verse 35 125 35. Verse 36 132 36. Verse 37 139 37. Verse 38 147 38. Verse 39 154 39. Verse 40 157 S. No. Title Page No. 40. Verse 41 161 41. Verse 42 168 42. Verse 43 175 43. Verse 44 184 44. Verse 45 187 45. Verse 46 190 46. Verse 47 192 47. Verse 48 196 48. Verse 49 200 49. Verse 50 204 50. Verse 51 206 51. Verse 52 208 52. Verse 53 210 53. Verse 54 212 54. Verse 55 216 CHAPTER - 11 Introduction : - All Vibhutis in form of Manifestations / Glories in world enumerated in Chapter 10. Previous Description : - Each object in creation taken up and Bagawan said, I am essence of that object means, Bagawan is in each of them… Bagawan is in everything. -

Five Elements Note

Five Elements Note: This is NOT our work and we are only providing this because we want to share the link with you, but links often get deleted. If the link has been removed, the info is below. Otherwise, find it at http://blog.aoma.edu/blog/bid/307306/Chinese-Medicine-School-Basic- Five-Element-Theory The theory of the natural elements is an enduring philosophy across cultures, appearing in separate countries in vastly different eras around the world. The ancient Greeks used the five elements of earth, water, air, fire, and “aether” (quintessence/spirit) as a guiding principal to better understand the universe. Both ancient Egyptians and Buddhists understood the elements as fire, water, air, and earth. Hinduism utilizes the five elements (earth, water, fire, wind, and “aether”) as well. In fact, the seven chakras pair with Hindu and Buddhist five element theory. Western astrology also makes use of the four classical elements in astrological charting. In Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), Five Element theory (also called Wu Xing) is a powerful, foundational lens through which medicine, our bodies, and the world at large can be viewed. Fire, Earth, Metal, Water, and Wood are understood to be the Five Elements in TCM. Each element is awarded a number of characteristics and correspondences. They all have their separate natures, movements, directions, sounds, times of the day, and much more. Similar to Yin Yang theory, many specific aspects of life and the world can be attributed to a certain element. In addition to these basic qualities, the elements also correspond with certain internal organs, tastes, emotions, and sense organs in Traditional Chinese Medicine—a very important feature of the theory with great implications to the medicinal practice. -

Possession and Deployment of Nuclear Weapons in South Asia an Assessment of Some Risks

Special articles Possession and Deployment of Nuclear Weapons in South Asia An Assessment of Some Risks This paper examines some of operational requirements and the dangers that come with the possibility that in the foreseeable future India and Pakistan may deploy their nuclear arsenals. The authors first describe the analytical basis for the inevitability of accidents in complex high-technology systems. Then they turn to potential failures of nuclear command and control and early warning systems as examples. They go on to discuss the possibility and consequences of accidental explosions involving nuclear weapons and their delivery systems. Finally some measures to reduce these risks are suggested. R RAJARAMAN, M V RAMANA, ZIA MIAN s citizens of nuclear armed states, ing periods of crises. Bruce Riedel, for- (DND) released by the National Security the people of India and Pakistan merly the Senior Director for Near East Advisory Board.4 It states that “India Amust confront the risks that go and South Asian Affairs at the US National shall pursue a doctrine of credible with possessing nuclear weapons. There Security Council, has disclosed that the minimum nuclear deterrence” and that is some public awareness of the holocaust “Pakistanis were preparing their nuclear this in turn requires that India maintain: that results when nuclear bombs are used arsenals for possible deployment” during (a) sufficient, survivable and operationally in warfare, a legacy of the ghastly attacks the 1999 Kargil crisis.1 Similarly, Raj prepared nuclear forces, (b) a robust com- by the US on the Japanese cities of Chengappa, a senior journalist with India mand and control system, (c) effective Hiroshima and Nagasaki over five decades Today with access to defence personnel, intelligence and early warning capabili- ago. -

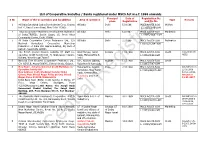

List of Cooperative Societies / Banks Registered Under MSCS Act W.E.F. 1986 Onwards Principal Date of Registration No

List of Cooperative Societies / Banks registered under MSCS Act w.e.f. 1986 onwards Principal Date of Registration No. S No Name of the Cooperative and its address Area of operation Type Remarks place Registration and file No. 1 All India Scheduled Castes Development Coop. Society All India Delhi 5.9.1986 MSCS Act/CR-1/86 Welfare Ltd.11, Race Course Road, New Delhi 110003 L.11015/3/86-L&M 2 Tribal Cooperative Marketing Development federation All India Delhi 6.8.1987 MSCS Act/CR-2/87 Marketing of India(TRIFED), Savitri Sadan, 15, Preet Vihar L.11015/10/87-L&M Community Center, Delhi 110092 3 All India Cooperative Cotton Federation Ltd., C/o All India Delhi 3.3.1988 MSCS Act/CR-3/88 Federation National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing L11015/11/84-L&M Federation of India Ltd. Sapna Building, 54, East of Kailash, New Delhi 110065 4 The British Council Division Calcutta L/E Staff Co- West Bengal, Tamil Kolkata 11.4.1988 MSCS Act/CR-4/88 Credit Converted into operative Credit Society Ltd , 5, Shakespeare Sarani, Nadu, Maharashtra & L.11016/8/88-L&M MSCS Kolkata, West Bengal 700017 Delhi 5 National Tree Growers Cooperative Federation Ltd., A.P., Gujarat, Odisha, Gujarat 13.5.1988 MSCS Act/CR-5/88 Credit C/o N.D.D.B, Anand-388001, District Kheda, Gujarat. Rajasthan & Karnataka L 11015/7/87-L&M 6 New Name : Ideal Commercial Credit Multistate Co- Maharashtra, Gujarat, Pune 22.6.1988 MSCS Act/CR-6/88 Amendment on Operative Society Ltd Karnataka, Goa, Tamil L 11016/49/87-L&M 23-02-2008 New Address: 1143, Khodayar Society, Model Nadu, Seemandhra, & 18-11-2014, Colony, Near Shivaji Nagar Police ground, Shivaji Telangana and New Amend on Nagar, Pune, 411016, Maharashtra 12-01-2017 Delhi. -

The Capabilities and Potential Effectiveness of India's Prithvi Missile Z

Science& Global Security, 1998,Volume 7, pp. 333-360 @ 1998 OPA (OverseasPublishers Association) N.V. Reprints available directly from the publisher Published by license under Photocopyingpermitted by license only the Gordon and Breach Publishersimprint. Printed in India Bringing Prithvi Down to Earth: The Capabilities and Potential Effectiveness of India's Prithvi Missile z. MianO, A.H. Nayyarb and M. V. Ramanac - Prelude: The following paper was written prior to Pakistan's test of the Ghauri missile in April 1998 and also India and Pakistan's May 1998 nuclear weapon tests. In recent years, the development, testing and ambiguous deployment status of India's short range Prithvi missile has caused great concern in Pakistan, and accelerated the missile race in South Asia. This paper summarizes the open literature descriptions of Prithvi and assessesthe military effectiveness of Prithvi if it is used with conventional warheads in attacks on Pakistani airfields, command centers, and radar installations. It is shown that the current accuracy of Prithvi is such that a very large number of missiles would be needed to damage or destroy such targets. Given India's large air force, the small number of Prithvi missiles that have been ordered by India's armed forces, and the much larger number of missiles required to pose a significant additional military threat to Pakistan, the justification for Prithvi is obviously open to question. It is suggested that the induction of Prithvi with its present limited capabilities may be largely a result of institutional pressure from India's Defense Research and Develop- ment Organization, which is responsible for the missile program, rather than demand from the armed forces. -

An Analytical and Comparative Study of Indian and Chinese Cosmologies

AN ANALYTICAL AND COMPARATIVE STUDY OF INDIAN AND CHINESE COSMOLOGIES S. MAHDIHASSAN* ABSTRACT To understand Chinese Cosmology in terms of the Indian system we have to look upon Cninese elements as symbols of the qualities they incorporate. The elements rearranged with the corresponding qualities would be : As elements: Fire. Water, Metal, Earth and Wood. As quali- ties: Hot, Cold, Dry, Moist, and Wind. Nothing can be drier than a metal hence dryness is symbolized as Metal. Subsoil is invariabry moist, hence moisture is symbolized as Earth. Wood is fresh - wood, like a cutting which transplants another life- form. It is potential life, like an egg, or better still here cosmic egg, the source of all creation. Its content is wind, like pneuma in Greek philosophy. Life-breath, the source of cosmic move- ment, cosmic existence, in fact cosmic soul. Life-energy is creative energy and Akasha as container would have cosmic soul as content. This makes wind (as cosmic) = Akasha, 1. A problem in comparative cosmology: By cosmology is understood a system of interpreting the universe III terms of few irreducible factors called Cosmic elements. Now \\ hatever exists in the universe can be either a form of matter, like star, stone and plant, or a form of energy, like heat and light. Further we must recognize entities as being independent of others, like stone as matter and heat as energy. Then what is merely relative, like heat and cold, these would be one and same entity, which concentrated would be called heat and reduced would be felt as cold. Thirdly there would be hypothetical entities logically justifiable but not knowable.