“Coder,” “Activist,” “Hacker”: Aaron Swartz in the Italian, UK, U.S., and Technology Press

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title A Web of Extended Metaphors in the Guerilla Open Access Manifesto of Aaron Swartz Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6w76f8x7 Author Swift, Kathy Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara A Web of Extended Metaphors in the Guerilla Open Access Manifesto of Aaron Swartz A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Education by Kathleen Anne Swift Committee in charge: Professor Richard Duran, Chair Professor Diana Arya Professor William Robinson September 2017 The dissertation of Kathleen Anne Swift is approved. ................................................................................................................................ Diana Arya ................................................................................................................................ William Robinson ................................................................................................................................ Richard Duran, Committee Chair June 2017 A Web of Extended Metaphors in the Guerilla Open Access Manifesto of Aaron Swartz Copyright © 2017 by Kathleen Anne Swift iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the members of my committee for their advice and patience as I worked on gathering and analyzing the copious amounts of research necessary to -

(US Innovation) Online Piracy Act of 2011

Insight Stop (U.S. Innovation) Online Piracy Act of 2011: OCTOBER 27, 2011 Yesterday the text for the Stop Online Piracy Act of 2011 was released, instantly causing an enormous, justified, uproar from online communities globally. If passed, this bill threatens to suffocate US innovation in technology, jeopardize the free flow of information online, and create further capital uncertainty for the our most innovative domestic companies. Bill Overview The bill is headed for the House of Representatives now to be heard by the House Judiciary Committee on November 16th. The authors, Representatives Lamar Smith (R-TX), John Conyers (D-MI), Bob Goodlatte (R- VA), and Howard Berman (D-CA) intended for the Stop Online Piracy Act to increase the government’s ability to disable websites deemed “foreign infringing sites.” A foreign infringing site is any “US Directed Site” that actively breaks the terms of a US law, agreement, or copyright. While this bill targets foreign sites, it applies to all sites that are “US Directed,” in other words, any site that provides content accessable by a US consumer. Net Neutrality: Enabling a Free Exchange of Information Net neutrality, in the simplest form, prohibits Internet Service Providers (ISPs) from restricting consumer’s access to information on the Internet based on content. This means that ISPs cannot block information, leaving consumers free to make informed decisions about their own online usage. While net neutrality only covers lawful content, the threat posed by the Stop Online Piracy Act is contained in a clause that allows immunity for any ISPs, search engines, domain registries, or similar gatekeepers with reasonable belief that the content is a foreign infringing site Enabling “Reasonable Doubt” as a Competitive Tool The online space is ripe for innovation because information is easily accessable and the barriers to entry are low. -

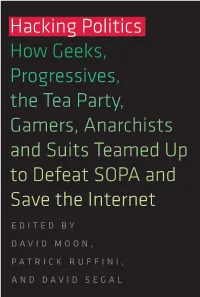

Hacking Politics How Geeks, Progressives, the Tea Party, Gamers, Anarchists and Suits Teamed up to Defeat SOPA and Save the Internet

Hacking Politics How Geeks, Progressives, the Tea Party, Gamers, Anarchists and Suits Teamed Up to Defeat SOPA and Save the Internet EDITED BY DAVID MOON, PATRICK RUFFINI, AND DAVID SEGAL Hacking Politics THE ULTIMATE DOCUMENTATION OF THE ULTIMATE INTERNET KNOCK-DOWN BATTLE! Hacking Politics From Aaron to Zoe—they’re here, detailing what the SOPA/PIPA battle was like, sharing their insights, advice, and personal observations. Hacking How Geeks, Politics includes original contributions by Aaron Swartz, Rep. Zoe Lofgren, Lawrence Lessig, Rep. Ron Paul, Reddit’s Alexis Ohanian, Cory Doctorow, Kim Dotcom and many other technologists, activists, and artists. Progressives, Hacking Politics is the most comprehensive work to date about the SOPA protests and the glorious defeat of that legislation. Here are reflections on why and how the effort worked, but also a blow-by-blow the Tea Party, account of the battle against Washington, Hollywood, and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce that led to the demise of SOPA and PIPA. Gamers, Anarchists DAVID MOON, former COO of the election reform group FairVote, is an attorney and program director for the million-member progressive Internet organization Demand Progress. Moon, Moon, and Suits Teamed Up PATRICK RUFFINI is founder and president at Engage, a leading digital firm in Washington, D.C. During the SOPA fight, he founded “Don’t Censor the to Defeat SOPA and Net” to defeat governmental threats to Internet freedom. Prior to starting Engage, Ruffini led digital campaigns for the Republican Party. Ruffini, Save the Internet DAVID SEGAL, executive director of Demand Progress, is a former Rhode Island state representative. -

Genius and the Soil

Genius and the soil DIGITAL COMMONS DIGITAL State and corporate interests have sought to crack talk in terms of protecting the interests of innovative individuals: authors, down on the power to share information digitally. But musicians, and scholars. To give just one could the new technologies point towards a more example, the Motion Picture Association of America, supported by some of the democratic model of creativity, asks JONATHAN GRAY biggest players in the film industry – Disney, Paramount, Sony, 20th Century ho can share what on from the 18th and 19th centuries. Reacting Fox, Universal and Warner Brothers – the internet? There is an against models of literary and artistic claims to pursue ‘commonsense solutions’ increasing awareness of creation that privileged imitation of the that ‘[protect] the rights of all who make debates around protected classics and striving towards perfection something of value with their minds, their material being shared within an established tradition, this period passion and their unique creative vision’. online through high profile court cases and saw a general turn towards the individual This notion of the individual controversies in the news, through things genius who broke previous rules and innovator, the lone pioneer breaking rules like the Pirate Bay, Wikileaks, or the recent invented new ones. Through this new and creating new paradigms, is only one tragic case of Aaron Swartz (see box, right). aesthetic frame, the world was divided side of the romantic story about literary But, stepping back from questions around into visionary and rebellious pioneers and creativity. The other side (perhaps less the law and its implementation in these slavish imitators. -

Dark and Deep Webs-Liberty Or Abuse

International Journal of Cyber Warfare and Terrorism Volume 9 • Issue 2 • April-June 2019 Dark and Deep Webs-Liberty or Abuse Lev Topor, Bar Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1836-5150 ABSTRACT While the Dark Web is the safest internet platform, it is also the most dangerous platform at the same time. While users can stay secure and almost totally anonymously, they can also be exploited by other users, hackers, cyber-criminals, and even foreign governments. The purpose of this article is to explore and discuss the tremendous benefits of anonymous networks while comparing them to the hazards and risks that are also found on those platforms. In order to open this dark portal and contribute to the discussion of cyber and politics, a comparative analysis of the dark and deep web to the commonly familiar surface web (World Wide Web) is made, aiming to find and describe both the advantages and disadvantages of the platforms. KeyWoRD Cyber, DarkNet, Information, New Politics, Web, World Wide Web INTRoDUCTIoN In June 2018, the United States Department of Justice uncovered its nationwide undercover operation in which it targeted dark web vendors. This operation resulted in 35 arrests and seizure of weapons, drugs, illegal erotica material and much more. In total, the U.S. Department of Justice seized more than 23.6$ Million.1 In that same year, as in past years, the largest dark web platform, TOR (The Onion Router),2 was sponsored almost exclusively by the U.S. government and other Western allies.3 Thus, an important and even philosophical question is derived from this situation- Who is responsible for the illegal goods and cyber-crimes? Was it the criminal[s] that committed them or was it the facilitator and developer, the U.S. -

Protect IP Act Summary

Summary: The PROTECT IP Act of 2011 This Summary describes the problem of rogue websites. It also explains how the PROTECT IP Act fights back against the criminals who operate and profit from those sites. As often happens during the legislative process, the Act may undergo various versions as it moves towards eventual passage. This Summary highlights the most important components of the Act, but please note that the details described below may change prior to passage. What are Rogue Websites? So-called “rogue websites” are foreign illegal websites that make money by distributing infringing copyrighted content or selling counterfeit goods. These offshore commercial websites receive more than 53-billion hits each year, and operate overseas with impunity because they cannot be reached by U.S. law enforcement. Rogue websites don’t pay U.S. taxes, contribute to the U.S. economy, promote U.S. jobs, manufacture creative content, or promote any social values. However, they are currently financed by U.S. consumers, U.S. advertisers, U.S. credit card companies, U.S. search engines, and domain name system server operators. Illegal offshore websites threaten both U.S. businesses and consumers. They are disguised to appear legitimate, and a consumer may be unaware they are visiting an illegal website or purchasing stolen or counterfeited goods. The foreign criminals who operate rogue websites can steal identities, sell personal information, install malicious software, or provide substandard or dangerous counterfeit goods (such as defective medical devices, pharmaceuticals, military goods, and other hard goods). They operate without fear of U.S. law enforcement, even while they present a clear and present danger to U.S. -

Report to the President: MIT and the Prosecution of Aaron Swartz

Report to the President MIT and the Prosecution of Aaron Swartz Review Panel Harold Abelson Peter A. Diamond Andrew Grosso Douglas W. Pfeiffer (support) July 26, 2013 © Copyright 2013, Massachusetts Institute of Technology This worK is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. PRESIDENT REIF’S CHARGE TO HAL ABELSON | iii L. Rafael Reif, President 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Building 3-208 Cambridge, MA 02139-4307 U.S.A. Phone 1-617-253-0148 !"#$"%&'(()'(*+,' ' -."%'/%01.220%'34.520#6' ' 78#9.'1"55'(*+*)':;<'="2'4..#'8#>05>.?'8#'.>.#@2'"%828#A'1%0B'"9@80#2'@"C.#'4&'3"%0#'7D"%@E'@0' "99.22'!7<FG'@=%0$A='@=.':;<'90BH$@.%'#.@D0%CI';'=">.'"2C.?'&0$)'"#?'&0$'=">.'A%"980$25&' "A%..?)'@0'%.>8.D':;<J2'8#>05>.B.#@I' ' <=.'H$%H02.'01'@=82'%.>8.D'82'@0'?.29%84.':;<J2'"9@80#2'"#?'@0'5."%#'1%0B'@=.BI'K0$%'%.>8.D' 2=0$5?'L+M'?.29%84.':;<J2'"9@80#2'"#?'?.98280#2'?$%8#A'@=.'H.%80?'4.A8##8#A'D=.#':;<'18%2@' 4.9"B.'"D"%.'01'$#$2$"5'!7<FGN%.5"@.?'"9@8>8@&'0#'8@2'#.@D0%C'4&'"'@=.#N$#8?.#@818.?'H.%20#)' $#@85'@=.'?."@='01'3"%0#'7D"%@E'0#'!"#$"%&'++)'(*+,)'L(M'%.>8.D'@=.'90#@.O@'01'@=.2.'?.98280#2'"#?' @=.'0H@80#2'@="@':;<'90#28?.%.?)'"#?'L,M'8?.#@81&'@=.'822$.2'@="@'D"%%"#@'1$%@=.%'"#"5&282'8#'0%?.%' @0'5."%#'1%0B'@=.2.'.>.#@2I' ' ;'@%$2@'@="@'@=.':;<'90BB$#8@&)'8#95$?8#A'@=02.'8#>05>.?'8#'@=.2.'.>.#@2)'"5D"&2'"9@2'D8@='=8A=' H%01.2280#"5'8#@.A%8@&'"#?'"'2@%0#A'2.#2.'01'%.2H0#284858@&'@0':;<I'P0D.>.%)':;<'@%8.2'90#@8#$0$25&' @0'8BH%0>.'"#?'@0'B..@'8@2'=8A=.2@'"2H8%"@80#2I';@'82'8#'@="@'2H8%8@'@="@';'"2C'&0$'@0'=.5H':;<'5."%#' 1%0B'@=.2.'.>.#@2I' -

Wikileaks, the First Amendment and the Press by Jonathan Peters1

WikiLeaks, the First Amendment and the Press By Jonathan Peters1 Using a high-security online drop box and a well-insulated website, WikiLeaks has published 75,000 classified U.S. documents about the war in Afghanistan,2 nearly 400,000 classified U.S. documents about the war in Iraq,3 and more than 2,000 U.S. diplomatic cables.4 In doing so, it has collaborated with some of the most powerful newspapers in the world,5 and it has rankled some of the most powerful people in the world.6 President Barack Obama said in July 2010, right after the release of the Afghanistan documents, that he was “concerned about the disclosure of sensitive information from the battlefield.”7 His concern spread quickly through the echelons of power, as WikiLeaks continued in the fall to release caches of classified U.S. documents. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton condemned the slow drip of diplomatic cables, saying it was “not just an attack on America's foreign policy interests, it [was] an attack on the 1 Jonathan Peters is a lawyer and the Frank Martin Fellow at the Missouri School of Journalism, where he is working on his Ph.D. and specializing in the First Amendment. He has written on legal issues for a variety of newspapers and magazines, and now he writes regularly for PBS MediaShift about new media and the law. E-mail: [email protected]. 2 Noam N. Levey and Jennifer Martinez, A whistle-blower with global resonance; WikiLeaks publishes documents from around the world in its quest for transparency, L.A. -

Guide De Protection Numérique Des Sources Journalistiques

Guide de Protection numérique des Sources journalistiques Mise en œuvre simplifiée Par Hector Sudan Version du document : 23.04.2021 Mises à jour disponibles gratuitement sur https://sourcesguard.ch/publications Guide de Protection numérique des Sources journalistiques Les journalistes ne sont pas suffisamment sensibilisés aux risques numé- riques et ne disposent pas assez d'outils pour s'en protéger. C'est la consta- tation finale d'une première recherche sociologique dans le domaine jour- nalistique en Suisse romande. Ce GPS (Guide de Protection numérique des Sources) est le premier résultat des recommandations de cette étude. Un GPS qui ne parle pas, mais qui va droit au but en proposant des solutions concrètes pour la sécurité numérique des journalistes et de leurs sources. Il vous est proposé une approche andragogique et tactique, de manière résumée, afin que vous puissiez mettre en œuvre rapidement des mesures visant à améliorer votre sécurité numérique, tout en vous permettant d'être efficient. Même sans être journaliste d'investigation, vos informations et votre protection sont importantes. Vous n'êtes peut-être pas directement la cible, mais pouvez être le vecteur d'une attaque visant une personne dont vous avez les informations de contact. Hector Sudan est informaticien au bénéfice d'un Brevet fédéral en technique des sys- tèmes et d'un MAS en lutte contre la crimina- lité économique. Avec son travail de master l'Artiste responsable et ce GPS, il se posi- tionne comme chercheur, formateur et consul- tant actif dans le domaine de la sécurité numé- rique pour les médias et journalistes. +41 76 556 43 19 keybase.io/hectorsudan [email protected] SourcesGuard Avant propos Ce GPS (Guide de Protection numérique des Sources journalistes) est à l’image de son acronyme : concis, clair, allant droit au but, tout en offrant la possibilité de passer par des chemins techniquement complexes. -

Disinformation, and Influence Campaigns on Twitter 'Fake News'

Disinformation, ‘Fake News’ and Influence Campaigns on Twitter OCTOBER 2018 Matthew Hindman Vlad Barash George Washington University Graphika Contents Executive Summary . 3 Introduction . 7 A Problem Both Old and New . 9 Defining Fake News Outlets . 13 Bots, Trolls and ‘Cyborgs’ on Twitter . 16 Map Methodology . 19 Election Data and Maps . 22 Election Core Map Election Periphery Map Postelection Map Fake Accounts From Russia’s Most Prominent Troll Farm . 33 Disinformation Campaigns on Twitter: Chronotopes . 34 #NoDAPL #WikiLeaks #SpiritCooking #SyriaHoax #SethRich Conclusion . 43 Bibliography . 45 Notes . 55 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This study is one of the largest analyses to date on how fake news spread on Twitter both during and after the 2016 election campaign. Using tools and mapping methods from Graphika, a social media intelligence firm, we study more than 10 million tweets from 700,000 Twitter accounts that linked to more than 600 fake and conspiracy news outlets. Crucially, we study fake and con- spiracy news both before and after the election, allowing us to measure how the fake news ecosystem has evolved since November 2016. Much fake news and disinformation is still being spread on Twitter. Consistent with other research, we find more than 6.6 million tweets linking to fake and conspiracy news publishers in the month before the 2016 election. Yet disinformation continues to be a substantial problem postelection, with 4.0 million tweets linking to fake and conspiracy news publishers found in a 30-day period from mid-March to mid-April 2017. Contrary to claims that fake news is a game of “whack-a-mole,” more than 80 percent of the disinformation accounts in our election maps are still active as this report goes to press. -

It Is NOT Junk a Blog About Genomes, DNA, Evolution, Open Science, Baseball and Other Important Things

it is NOT junk a blog about genomes, DNA, evolution, open science, baseball and other important things The Past, Present and Future of Scholarly Publishing By MIC H A EL EISEN | Published: MA RC H 2 8 , 2 0 1 3 Search To search, type and hit enter I gave a talk last night at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco about science publishing and PLoS. There will be an audio link soon, but, for the first time in my life, Michael Eisen I actually gave the talk (largely) from prepared remarks, so I thought I’d post it here. I'm a biologist at UC An audio recording of the talk with Q&A is available here. Berkeley and an Investigator of the —— Howard Hughes Medical Institute. I work primarily On January 6, 2011, 24 year old hacker and activist Aaron Swartz was arrested by on flies, and my research encompases police at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for downloading several million evolution, development, genetics, articles from an online archive of research journals called JSTOR. genomics, chemical ecology and behavior. I am a strong proponent of After Swartz committed suicide earlier this year in the face of legal troubles arising open science, and a co-founder of the from this incident, questions were raised about why MIT, whose access to JSTOR he Public Library of Science. And most exploited, chose to pursue charges, and what motivated the US Department of Justice importantly, I am a Red Sox fan. (More to demand jail time for his transgression. about me here). -

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Role of Corporate and Government Surveillance in Shifting Journalistic Information Security Practices Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9p22j7q3 Author Shelton, Martin Publication Date 2015 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The Role of Corporate and Government Surveillance in Shifting Journalistic Information Security Practices DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Information and Computer Science by Martin L. Shelton Dissertation Committee: Professor Bonnie A. Nardi, Chair Professor Judith S. Olson Professor Victoria Bernal 2015 © 2015 Martin Shelton This document is distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vi CURRICULUM VITAE viii ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION ix SECTION 1: Introduction and Context 1 CHAPTER 1: The Impulse for Information Security in Investigative 2 Journalism 1.1 Motivations 6 1.2 Research Scope 9 CHAPTER 2: Literature Review 12 2.1 Journalistic Ideologies 12 2.1.1 Investigative Routines and Ideologies 15 2.2 Panoptic Enforcement of Journalism 17 2.3 Watching the Watchdogs 21 2.4 The Decentralization and Normalization of Surveillance 27 SECTION 2: Findings 30 CHAPTER 3: Methods 31 3.1 Gathering Surveillance