Master Plans and Patterns of Segregation Among Muslims in Delhi1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Trajectory of a Struggle

SSHAHRIHAHRI AADHIKARDHIKAR MMANCH:ANCH: BBEGHARONEGHARON KKEE SSAATHAATH ((URBANURBAN RRIGHTSIGHTS FFORUM:ORUM: WWITHITH TTHEHE HHOMELESS)OMELESS) TTHEHE TTRAJECTORYRAJECTORY OOFF A SSTRUGGLETRUGGLE i Published by: Shahri Adhikar Manch: Begharon Ke Saath G-18/1 Nizamuddin West Lower Ground Floor New Delhi – 110 013 +91-11-2435-8492 [email protected] Text: Jaishree Suryanarayan Editing: Shivani Chaudhry and Indu Prakash Singh Design and printing: Aspire Design March 2014, New Delhi Printed on CyclusPrint based on 100% recycled fibres SSHAHRIHAHRI AADHIKARDHIKAR MMANCH:ANCH: BBEGHARONEGHARON KKEE SSAATHAATH ((URBANURBAN RRIGHTSIGHTS FFORUM:ORUM: WWITHITH TTHEHE HHOMELESS)OMELESS) TTHEHE TTRAJECTORYRAJECTORY OOFF A SSTRUGGLETRUGGLE Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Objective and Methodology of this Study 2 2. BACKGROUND 3 2.1 Defi nition and Extent of Homelessness in Delhi 3 2.2 Human Rights Violations Faced by Homeless Persons 5 2.3 Criminalisation of Homelessness 6 2.4 Right to Adequate Housing is a Human Right 7 2.5 Past Initiatives 7 3. FORMATION AND GROWTH OF SHAHRI ADHIKAR MANCH: BEGHARON KE SAATH 10 3.1 Formation of Shahri Adhikar Manch: Begharon Ke Saath (SAM:BKS) 10 3.2 Vision and Mission of SAM:BKS 11 3.3 Functioning of SAM:BKS 12 4. STRATEGIC INTERVENTIONS 14 4.1 Strategies Used by SAM:BKS 14 4.2 Intervention by SAM:BKS in the Suo Moto Case in the High Court of Delhi 16 4.3 Media Advocacy 19 4.4 Campaigns of SAM:BKS for Facilitating Access to Entitlements and Realisation of Human Rights 20 5. THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA AND THE ISSUE OF HOMELESSNESS 22 5.1 Role of the Offi ce of Supreme the Court Commissioners in the ‘Right to Food’ Case 22 6. -

Slum Rehabilitation in Delhi

WHOSE CITY IS IT ANYWAY? KRISHNA RAJ FELLOWSHIP PROJECT Madhulika Khanna, Keshav Maheshwari, Resham Nagpal, Ravideep Sethi, Sandhya Srinivasan August 2011 Delhi School of Economics 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank our professor, Dr. Anirban Kar, who gave direction to our research and coherence to our ideas. We would like to express our gratitude towards Mr. Dunu Roy and everyone at the Hazards Centre for their invaluable inputs. We would also like to thank all our respondents for their patience and cooperation. We are grateful to the Centre for Development Economics, Delhi School of Economics for facilitating our research. CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 1 2. POLICY FRAMEWORK ...................................................................................................................... 2 2.1. SLUM POLICY IN DELHI ............................................................................................................ 2 2.2. SLUM REHABILITATION PROCESS ........................................................................................... 4 2.2.1. IN-SITU UP-GRADATION .................................................................................................. 4 2.2.2. RELOCATION.................................................................................................................... 4 3. RIGHTS AND CITIZENSHIP ............................................................................................................... -

The Challenge of “Human” Sustainability for Indian Mega-Cities: Squatter Settlements, Forced Evictions and Resettlement & Rehabilitation Policies in Delhi

V. Dupont Do not quote without the author’s permission Paper presented to: XXVII IUSSP International Population Conference Busan, Corea, 26-31 August 2013 Session 282: The sustainability of mega-cities The challenge of “human” sustainability for Indian mega-cities: Squatter settlements, forced evictions and resettlement & rehabilitation policies in Delhi Véronique Dupont Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (Institute of Research for Development) Email: [email protected] Abstract This paper deals with the “human” dimension of sustainability in Indian mega-cities, specially the issue of social equity approached through the housing requirements of the urban poor. Indian mega-cities are faced with an acute shortage in adequate housing, which has resulted in the growth of illegal slums or squatter settlements. Since the 1990s, the implementation of urban renewal projects, infrastructure expansion and “beautification” drives, in line with the requirements of globalising cities, have resulted in many slum demolitions, which increased the numbers of homeless people. Delhi exemplifies such trends. This paper’s main objective is to appraise the adequacy of slum clearance and resettlement and rehabilitation policies implemented in Delhi in order to address the challenge of slums. Do such policies alleviate the problem of lack of decent housing for the urban poor, or to what extent do they also aggravate their situation? It combines two approaches: firstly, a statistical assessment of squatters’ relocation and slum demolition without resettlement over the last two decades, completed by an analysis of the conditions of implementation of the resettlement policy; and, secondly, a qualitative and critical analysis of the recently launched strategy of in-situ rehabilitation under public- private partnership. -

Public Interest Litigation and Political Society in Post-Emergency India

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Columbia University Academic Commons Competing Populisms: Public Interest Litigation and Political Society in Post-Emergency India Anuj Bhuwania Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2013 © 2013 Anuj Bhuwania All rights reserved ABSTRACT Competing Populisms: Public Interest Litigation and Political Society in Post-Emergency India Anuj Bhuwania This dissertation studies the politics of ‘Public Interest Litigation’ (PIL) in contemporary India. PIL is a unique jurisdiction initiated by the Indian Supreme Court in the aftermath of the Emergency of 1975-1977. Why did the Court’s response to the crisis of the Emergency period have to take the form of PIL? I locate the history of PIL in India’s postcolonial predicament, arguing that a Constitutional framework that mandated a statist agenda of social transformation provided the conditions of possibility for PIL to emerge. The post-Emergency era was the heyday of a new form of everyday politics that Partha Chatterjee has called ‘political society’. I argue that PIL in its initial phase emerged as its judicial counterpart, and was even characterized as ‘judicial populism’. However, PIL in its 21 st century avatar has emerged as a bulwark against the operations of political society, often used as a powerful weapon against the same subaltern classes whose interests were so loudly championed by the initial cases of PIL. In the last decade, for instance, PIL has enabled the Indian appellate courts to function as a slum demolition machine, and a most effective one at that – even more successful than the Emergency regime. -

Immersion Emergence

immersion emergence ISBN 81-7525-751-2 ravi agarwal immersion emergence the shroud : self-portrait ravi agarwal April 27, 2006 Copyright © 2006 by Ravi Agarwal All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy- ing, recording, or by any form of information storage and retireval system, without permission in writing fromt e publisher. Published by Ravi Agarwal, New Delhi, India. E-mail [email protected] to order copies. Price: Rs 300 (India) / USD 25 (international); postage at actuals Printed in India by Ajanta Offset & Packagings Limited ISBN xxx To my parents Acknowledgements To the river waters, who let me in. To those who live on and around it. To my friends, family and colleagues, who were there at my asking, some all the while, some who joined along the way, or had to leave, even as I came and went. Nanni, Bharat, Aniruddha and Anjali, Salil and Monika, Amit, Jeebesh, Sveta, Monica, Rana, Shuddha, Dorothea, Sonia, Gauri, Gayatri, Bina, Sharda, Alka, Reena. To Ritika and to Anand, who directly participated in and helped deepen my explorations. To Geeti Sen for my first river writing. To my colleagues and friends at Toxics Link who accepted me on my own terms. To Cdr. Siddeshwar Sinha and Dunu Roy, who graciously shared their knowledge about the river. To Jeebesh for forever unfailingly showing my mind a light. To Naintara for patiently shooting me in “The Shroud”. To Aniruddha and Salil for lovingly designing and producing this. To my elusive inseparable Varda. -

JOURNEY SO FAR of the River Drain Towards East Water

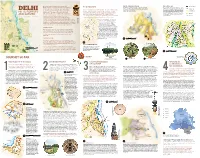

n a fast growing city, the place of nature is very DELHI WITH ITS GEOGRAPHICAL DIVISIONS DELHI MASTER PLAN 1962 THE REGION PROTECTED FOREST Ichallenging. On one hand, it forms the core framework Based on the geology and the geomorphology, the region of the city of Delhi The first ever Master plan for an Indian city after independence based on which the city develops while on the other can be broadly divided into four parts - Kohi (hills) which comprises the hills of envisioned the city with a green infrastructure of hierarchal open REGIONAL PARK Spurs of Aravalli (known as Ridge in Delhi)—the oldest fold mountains Aravalli, Bangar (main land), Khadar (sandy alluvium) along the river Yamuna spaces which were multi functional – Regional parks, Protected DELHI hand, it faces serious challenges in the realm of urban and Dabar (low lying area/ flood plains). greens, Heritage greens, and District parks and Neighborhood CULTIVATED LAND in India—and river Yamuna—a tributary of river Ganga—are two development. The research document attempts to parks. It also included the settlement of East Delhi in its purview. HILLS, FORESTS natural features which frame the triangular alluvial region. While construct a perspective to recognize the role and value Moreover the plan also suggested various conservation measures GREENBELT there was a scattering of settlements in the region, the urban and buffer zones for the protection of river Yamuna, its flood AND A RIVER of nature in making our cities more livable. On the way, settlements of Delhi developed, more profoundly, around the eleventh plains and Ridge forest. -

Copyright by Nathan Alexander Moore 2016

Copyright by Nathan Alexander Moore 2016 The Report committee for Nathan Alexander Moore Certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: Redefining Nationalism: An examination of the rhetoric, positions and postures of Asaduddin Owaisi APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: _______________________ Syed Akbar Hyder, Supervisor ______________________ Gail Minault Redefining Nationalism: An examination of the rhetoric, positions and postures of Asaduddin Owaisi by Nathan Alexander Moore, B.A. Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin December 2016 Abstract Redefining Nationalism: An examination of the rhetoric, positions and postures of Asaduddin Owaisi Nathan Alexander Moore, MA The University of Texas at Austin, 2016 Supervisor: Syed Akbar Hyder Asaduddin Owaisi is the leader of the political party, All India Majlis-e-Ittehad-ul- Muslimeen, and also the latest patriarch in a family dynasty stretching at least three generations. Born in Hyderabad in 1969, in the last twelve years, he has gained national prominence as Member of Parliament who espouses Muslim causes more forcefully than any other Indian Muslim. To his devotees, he is the Naqib-e-Millat-The Captain of the community. To his detractors he is “communalist” and an “opportunist.” He is an astute political force that is changing the face and tone of Indian politics. This report examines Owaisi’s rhetoric and postures to further study Muslim-Indian identity in the Indian Republic. Owaisi’s calls for the Muslims to uplift themselves also echo the calls of Muhammad Iqbal (d. -

Introduction to Indian Politics

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Introduction to Indian Politics Borooah, Vani University of Ulster December 2015 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/76597/ MPRA Paper No. 76597, posted 05 Feb 2017 07:28 UTC Chapter 1 Introduction to Indian Politics In his celebrated speech, delivered to India’s Constituent Assembly on the eve of the 15th August 1947, to herald India’s independence from British rule, Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first Prime Minister, famously asked if the newly independent nation was “brave enough and wise enough to grasp this opportunity and accept the challenge of the future”. If one conceives of India, as many Indians would, in terms of a trinity of attributes – democratic in government, secular in outlook, and united by geography and a sense of nationhood – then, in terms of the first of these, it would appear to have succeeded handsomely. Since, the Parliamentary General Election of 1951, which elected the first cohort of members to its lower house of Parliament (the Lok Sabha), India has proceeded to elect, in unbroken sequence, another 15 such cohorts so that the most recent Lok Sabha elections of 2014 gave to the country a government drawn from members to the 16th Lok Sabha. Given the fractured and fraught experiences with democracy of India’s immediate neighbours (Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Myanmar) and of a substantial number of countries which gained independence from colonial rule, it is indeed remarkable that independent India has known no other form of governmental authority save through elections. Elections (which represent ‘formal democracy’), are a necessary, but not a sufficient, condition for ‘substantive democracy’. -

Rajya Sabha and Its Secretariat a Performance Profile 2013

Rajya Sabha and its Secretariat A Performance Profile 2013 RAJYA SABHA SECRETARIAT PRINTED BY THE GENERAL MANAGER NEW DELHI GOVERNMENT OF INDIA PRESS, MINTO ROAD, NEW DELHI-110002 NOVEMBER 2014 Hindi version of the Publication is also available PARLIAMENT OF INDIA Rajya Sabha and its Secretariat: A Performance Profile—2013 RAJYA SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI NOVEMBER 2014 F.No. RS.2/1/2014-PWW © 2014 Rajya Sabha Secretariat Rajya Sabha Website: http://parliamentofindia.nic.in http://rajyasabha.nic.in E-mail : [email protected] Price: ` 60.00 Published by Secretary-General, Rajya Sabha and Printed by the General Manager, Government of India Press, Minto Road, New Delhi. P R E F A C E This publication provides information about the work transacted by the Rajya Sabha, its Committees and the Secretariat during the year 2013. It is meant to familiarize the readers with different aspects of the functioning of the Rajya Sabha. As an overview, it provides relevant details which are interesting about the working of Parliament and will be of use to the Members of Parliament as well as the general public. NEW DELHI; SHUMSHER K. SHERIFF November 2014 Secretary-General, Rajya Sabha. C O N T E N T S PAGES 1. House at Work (i) Question Hour . 1-2 (ii) Legislation . 2 (iii) Significant legislative developments during the year 2013 . 2—8 (iv) Discussion on the working of the Ministries . 8 (v) Discussion on matters of urgent public importance . 9 (vi) Private Members’ Resolutions . 9-10 (vii) Statutory Resolutions . 10 (viii) Government Resolutions . 10-11 (ix) Motions under Rule 168 (No-Day-Yet-Named Motions)……. -

A River and the Riverfront: Delhi's Yamuna As an In-Between Space

ARTICLE IN PRESS City, Culture and Society ■■ (2015) ■■–■■ Contents lists available at ScienceDirect City, Culture and Society journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ccs A river and the riverfront: Delhi’s Yamuna as an in-between space Awadhendra Sharan * Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, 29, Rajpur Road, Delhi 110054, India ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: This essay examines the presence of Yamuna in the city of Delhi, from two perspectives: (i) understand- Available online ing riverscapes as simultaneously aquatic and terrestrial and (ii) understanding these as conjoining issues of environment and technology. With events over the course of the last century as its backdrop, the essay Keywords: focuses on the last few decades of the twentieth century, to examine the relation of land and river in Yamuna Delhi; the interface of people and projects, especially the issue of slums; and the risks posed to the river Pollution on account of waste and pollution. All these featured prominently in the events leading up to the staging River of the Commonwealth Games in Delhi in October 2010, which provides the most immediate context for Nature Sustainability this essay. In conclusion, I propose that the current strategies of rejuvenating the river are limited, often Planning anti-poor and far from sustainable. © 2014 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Introduction elsewhere, was a means to brand the city and to manufacture solidarities around an urban place ‘by Over the last decade and more Delhi aspired to imbuing it with an affective charge, a structure of transit from a ‘walled city’ to a ‘world city’.1 In the feeling that is generated by the scale, compression process, it attempted, or at least its elite groups en- and celebratory content of the event itself’ (Baviskar, deavoured, to reshape spatial arrangements, 2011b). -

HOMELESSNESS ABOUT BUTTERFLIES Children in News Homelessness

HOMELESSNESS ABOUT BUTTERFLIES Children in News Homelessness VOL. XXIV, 2015 HIS NAME IS TODAY Years V 1989 -2014 OL. XXIV , 2015 U-4, Green Park Extension, New Delhi-110016 CHILDREN IN NEWS VOL XXIV, 2015 1 Tel.: 26163935, 26191063 E-mail: [email protected] Delhi Child Rights Club The Delhi Child Rights Club (DCRC) was launched by BUTTERFLIES in 1998. There was a need to have a children's forum in Delhi where children could articulate their issues and collectively take action to get their entitlements which is rightfully theirs. BUTTERFLIES invited children of NGOs working with children based in Delhi to be part of this forum. The response to this invitation was encouraging. Today there are children from 15 NGOs who are members In the little world in which and in recent times children from various neighbourhoods have attended DCRC meetings. The primary objective of DCRC is to have children's voices heard by civil society and policy makers, their views on issues children have their existence pertaining to their lives be taken seriously, and to consult them on all issues related to their welfare, development and protection. DCRC is open to all children of Delhi under 18 years of age whether from working whosoever brings them up,there is class, middle class or upper class background or a child living in an institution. A city-wide Child Rights Club is one mechanism where by children can work together towards the creation of a child safe and nothing so finely perceived and so friendly city. The children envisage a city where children's rights to respect, dignity, opportunities, growth, development and protection are ensured. -

Reference Books List

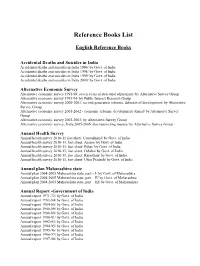

Reference Books List English Reference Books Accidental Deaths and Suicides in India Accidental deaths and suicides in India 1996/ by Govt. of India Accidental deaths and suicides in India 1998/ by Govt. of India Accidental deaths and suicides in India 1999/ by Govt. of India Accidental deaths and suicides in India 2000/ by Govt. of India Alternative Economic Survey Alternative economic survey 1991-98: seven years of structural adjustment/ by Alternative Survey Group Alternative economic survey 1993-94/ by Public Interest Research Group Alternative economic survey 2000-2001: second generation reforms, delusion of development/ by Alternative Survey Group Alternative economic survey 2001-2002 - economic reforms: development denied/ by Alternative Survey Group Alternative economic survey 2002-2003/ by Alternative Survey Group Alternative economic survey, India 2005-2006: disempowering masses/ by Alternative Survey Group Annual Health Survey Annual health survey 2010-11 fact sheet: Uttarakhand/ by Govt. of India Annual health survey 2010-11, fact sheet: Assam/ by Govt. of India Annual health survey 2010-11, fact sheet: Bihar/ by Govt. of India Annual health survey 2010-11, fact sheet: Odisha/ by Govt. of India Annual health survey 2010-11, fact sheet: Rajasthan/ by Govt. of India Annual health survey 2010-11, fact sheet: Uttar Pradesh/ by Govt. of India Annual plan Maharashtra state Annual plan 2004-2005 Maharashtra state, part – I/ by Govt. of Maharashtra Annual plan 2004-2005 Maharashtra state, part – II/ by Govt. of Maharashtra Annual plan 2004-2005 Maharashtra state, part – III/ by Govt. of Maharashtra Annual Report -Government of India Annual report 1971-72/ by Govt. of India Annual report 1983-84/ by Govt.