M^^Ttx of ^Iiiloibiopijp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Nathan Alexander Moore 2016

Copyright by Nathan Alexander Moore 2016 The Report committee for Nathan Alexander Moore Certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: Redefining Nationalism: An examination of the rhetoric, positions and postures of Asaduddin Owaisi APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: _______________________ Syed Akbar Hyder, Supervisor ______________________ Gail Minault Redefining Nationalism: An examination of the rhetoric, positions and postures of Asaduddin Owaisi by Nathan Alexander Moore, B.A. Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin December 2016 Abstract Redefining Nationalism: An examination of the rhetoric, positions and postures of Asaduddin Owaisi Nathan Alexander Moore, MA The University of Texas at Austin, 2016 Supervisor: Syed Akbar Hyder Asaduddin Owaisi is the leader of the political party, All India Majlis-e-Ittehad-ul- Muslimeen, and also the latest patriarch in a family dynasty stretching at least three generations. Born in Hyderabad in 1969, in the last twelve years, he has gained national prominence as Member of Parliament who espouses Muslim causes more forcefully than any other Indian Muslim. To his devotees, he is the Naqib-e-Millat-The Captain of the community. To his detractors he is “communalist” and an “opportunist.” He is an astute political force that is changing the face and tone of Indian politics. This report examines Owaisi’s rhetoric and postures to further study Muslim-Indian identity in the Indian Republic. Owaisi’s calls for the Muslims to uplift themselves also echo the calls of Muhammad Iqbal (d. -

Introduction to Indian Politics

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Introduction to Indian Politics Borooah, Vani University of Ulster December 2015 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/76597/ MPRA Paper No. 76597, posted 05 Feb 2017 07:28 UTC Chapter 1 Introduction to Indian Politics In his celebrated speech, delivered to India’s Constituent Assembly on the eve of the 15th August 1947, to herald India’s independence from British rule, Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first Prime Minister, famously asked if the newly independent nation was “brave enough and wise enough to grasp this opportunity and accept the challenge of the future”. If one conceives of India, as many Indians would, in terms of a trinity of attributes – democratic in government, secular in outlook, and united by geography and a sense of nationhood – then, in terms of the first of these, it would appear to have succeeded handsomely. Since, the Parliamentary General Election of 1951, which elected the first cohort of members to its lower house of Parliament (the Lok Sabha), India has proceeded to elect, in unbroken sequence, another 15 such cohorts so that the most recent Lok Sabha elections of 2014 gave to the country a government drawn from members to the 16th Lok Sabha. Given the fractured and fraught experiences with democracy of India’s immediate neighbours (Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Myanmar) and of a substantial number of countries which gained independence from colonial rule, it is indeed remarkable that independent India has known no other form of governmental authority save through elections. Elections (which represent ‘formal democracy’), are a necessary, but not a sufficient, condition for ‘substantive democracy’. -

Rajya Sabha and Its Secretariat a Performance Profile 2013

Rajya Sabha and its Secretariat A Performance Profile 2013 RAJYA SABHA SECRETARIAT PRINTED BY THE GENERAL MANAGER NEW DELHI GOVERNMENT OF INDIA PRESS, MINTO ROAD, NEW DELHI-110002 NOVEMBER 2014 Hindi version of the Publication is also available PARLIAMENT OF INDIA Rajya Sabha and its Secretariat: A Performance Profile—2013 RAJYA SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI NOVEMBER 2014 F.No. RS.2/1/2014-PWW © 2014 Rajya Sabha Secretariat Rajya Sabha Website: http://parliamentofindia.nic.in http://rajyasabha.nic.in E-mail : [email protected] Price: ` 60.00 Published by Secretary-General, Rajya Sabha and Printed by the General Manager, Government of India Press, Minto Road, New Delhi. P R E F A C E This publication provides information about the work transacted by the Rajya Sabha, its Committees and the Secretariat during the year 2013. It is meant to familiarize the readers with different aspects of the functioning of the Rajya Sabha. As an overview, it provides relevant details which are interesting about the working of Parliament and will be of use to the Members of Parliament as well as the general public. NEW DELHI; SHUMSHER K. SHERIFF November 2014 Secretary-General, Rajya Sabha. C O N T E N T S PAGES 1. House at Work (i) Question Hour . 1-2 (ii) Legislation . 2 (iii) Significant legislative developments during the year 2013 . 2—8 (iv) Discussion on the working of the Ministries . 8 (v) Discussion on matters of urgent public importance . 9 (vi) Private Members’ Resolutions . 9-10 (vii) Statutory Resolutions . 10 (viii) Government Resolutions . 10-11 (ix) Motions under Rule 168 (No-Day-Yet-Named Motions)……. -

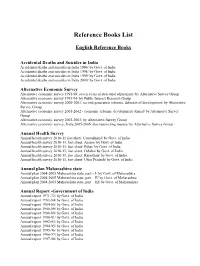

Reference Books List

Reference Books List English Reference Books Accidental Deaths and Suicides in India Accidental deaths and suicides in India 1996/ by Govt. of India Accidental deaths and suicides in India 1998/ by Govt. of India Accidental deaths and suicides in India 1999/ by Govt. of India Accidental deaths and suicides in India 2000/ by Govt. of India Alternative Economic Survey Alternative economic survey 1991-98: seven years of structural adjustment/ by Alternative Survey Group Alternative economic survey 1993-94/ by Public Interest Research Group Alternative economic survey 2000-2001: second generation reforms, delusion of development/ by Alternative Survey Group Alternative economic survey 2001-2002 - economic reforms: development denied/ by Alternative Survey Group Alternative economic survey 2002-2003/ by Alternative Survey Group Alternative economic survey, India 2005-2006: disempowering masses/ by Alternative Survey Group Annual Health Survey Annual health survey 2010-11 fact sheet: Uttarakhand/ by Govt. of India Annual health survey 2010-11, fact sheet: Assam/ by Govt. of India Annual health survey 2010-11, fact sheet: Bihar/ by Govt. of India Annual health survey 2010-11, fact sheet: Odisha/ by Govt. of India Annual health survey 2010-11, fact sheet: Rajasthan/ by Govt. of India Annual health survey 2010-11, fact sheet: Uttar Pradesh/ by Govt. of India Annual plan Maharashtra state Annual plan 2004-2005 Maharashtra state, part – I/ by Govt. of Maharashtra Annual plan 2004-2005 Maharashtra state, part – II/ by Govt. of Maharashtra Annual plan 2004-2005 Maharashtra state, part – III/ by Govt. of Maharashtra Annual Report -Government of India Annual report 1971-72/ by Govt. of India Annual report 1983-84/ by Govt. -

Change Is on Its Way January 5, 2014 S

Established 1946 Price : Rupees Five Vol. 68 No. 52 Change is on its way January 5, 2014 S. Viswam The first task for all of us here already formed a government in in Janata, a pleasant one, is to wish Profligate legislators Delhi. It has announced that it intends all our readers a happy 2014. In the Kuldip Nayar to go national and field a substantial context of national politics, the year number of candidates for Parliament. we have just ushered in is a crucial The party is not lacking in public Apartheid of the world unite! one for the polity and the country. support for its unconventional style K. S. Chalam We begin 2014, as we have done of politics. The people at large are with earlier new year arrivals, with funding it in a surprisingly big way. hope laced with abundant optimism. Its anti-corruption crusade, initially No roadblocks for AAP agenda The year we have just rung out did launched under Hazare’s inspiration Nitish Chakravarty not meet with all our expectations. and leadership, has caught popular Indeed, it left us highly dissatisfied, imagination, which has been further displeased and even angry. But it has fortified by the welfare measures set gone. Let it go. Why I am not in AAP? in by the Kejriwal government. In Sandeep Pandey short, the ground has been laid, and But in its own way, it gave some now exists, in many states of India, for shape and substance to its successor by a pan-Indian entry into the national Communal violence in 2013 ushering in some important changes mainstream politics by the AAP. -

The Journal of Parliamentary Information

The Journal of Parliamentary Information VOLUME LVII NO. 2 JUNE 2011 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI CBS Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd. 24, Ansari Road, Darya Ganj, New Delhi-2 2009 issue, EDITORIAL BOARD Editor : T.K. Viswanathan Secretary-General Lok Sabha Associate Editor : P.K. Misra Joint Secretary Lok Sabha Secretariat Kalpana Sharma Director Lok Sabha Secretariat Assistant Editors : Pulin B. Bhutia Joint Director Lok Sabha Secretariat Sanjeev Sachdeva Joint Director Lok Sabha Secretariat © Lok Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi for approval. THE JOURNAL OF PARLIAMENTARY INFORMATION VOLUME LVII NO. 2 JUNE 2011 CONTENTS PAGE EDITORIAL NOTE 101 ADDRESSES Address by the President to Parliament, 21 February 2011 103 ARTICLE Parliamentary Oversight of Human Rights: A Case Study of Disability in India—Deepali Mathur 116 PARLIAMENTARY EVENTS AND ACTIVITIES Conferences and Symposia 123 Birth Anniversaries of National Leaders 124 Exchange of Parliamentary Delegations 125 Bureau of Parliamentary Studies and Training 127 PRIVILEGE ISSUES 129 PROCEDURAL MATTERS 131 PARLIAMENTARY AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENTS 135 DOCUMENTS OF CONSTITUTIONAL AND PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST 143 SESSIONAL REVIEW Lok Sabha 151 Rajya Sabha 184 State Legislatures 205 RECENT LITERATURE OF PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST 210 APPENDICES I. Statement showing the work transacted during the Seventh Session of the Fifteenth Lok Sabha 219 (iv) II. Statement showing the work transacted during the Two Hundred and Twenty-Second Session of the Rajya Sabha 223 III. Statement showing the activities of the Legislatures of the States and Union Territories during the period 1 January to 31 March 2011 228 IV. List of Bills passed by the Houses of Parliament and assented to by the President during the period 1 January to 31 March 2011 235 V. -

Coalition Governments in India: an Evaluation of United Progressive Alliance Government -1

COALITION GOVERNMENTS IN INDIA: AN EVALUATION OF UNITED PROGRESSIVE ALLIANCE GOVERNMENT -1 SUBMITT&O )N {^/tRTlACIULFILLMEN liREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF (i^i m ^ 3n » POLITICAL SCIENCE By AgM^ QAZI Under the Supervision of Dr. IFTEKHAR AHEMMED (ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR) DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY AUGARH (INDIA) 2014 2 4 NCV 2014 DS4380 il Q © ® © ® e Dr. IFTEKHARAHEMMED Telephones: Associate Professor Chairman: 0571-2^01720 DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE AMUPABX: 700916/7000920-21-22 Aligarh Muslim University Chairman: 1561 Aligarh - 202002 Office: 1560 <Date: •>^/ij_^l^^^9 Certificate '> . Tliis is io certify tHat^tHe (Dissertation *CoaQ.tion governments in India: Jin ^abuUion of Vnited (Progressive At^nce government - I" Sy !Wr. Mudam' Jifimad Qizi is the originaC researcd wor^ of the candidate, and is suitaMe for submission as the partiaCfidfittmentfor the award of the (Degree of Master of (PhUosophy in (PoCiticaCScienc^. ^i } tg O' /• yr-5S Dr. Iftekhar Ahemmed (Supervisor) DECLARATION I hereby declare that the dissertation "Coalition Governments in India: An Evaluation of United Progressive Alliance Government-I" submitted for the award of the degree of Master of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science is based on my original research work and the dissertation has not been presented for any other degree of this University or any other University or Institution and that all sources used in this work have been thoroughly acknowledged. Place: A w^ vJ /NUcv^^^ MudaHfAhmad Qazi Date: 9o | ) o | >o \<^ -

Institutionalizing Constitutional Rights

Development, Diversity and Equal Opportunity in India DRAFT FOR CIRCULATION | June 10th 2015 Development, Diversity and Equal Opportunity in India Abusaleh Shariff Executive Director and Chief Scholar US-India Policy Institute Washington D. C A background paper circulated at a Public Lecture at the University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia June 2015 1 Dedication Excerpts from a book by this author which is in press with Oxford University Press: ‘Institutionalizing Constitutional Rights in India: Post-Sachar Committee Scenario’ This book is dedicated to my mentors who taught me to look around the world and understand its beauty in its complexity and diversity; also gave a vision to describe it to the world at large. Sri. Abdulla Hussain - teacher and my father, taught early practical lessons in diversity Prof. John C. Caldwell and Mrs. Pat Caldwell - taught to document and sustain the sanctity of filed based empirical research, and Justice (Retired) Rajinder Sachar - enabled an understanding of the human rights which are ingrained in democracy Acknowledgments The motivation to write this book emerged from my special occasion discussions undertaken with Dr. Manmohan Singh, Ex Prime Minster of India, Sri. Hamid Ansari, the Vice President of India and Just. (Rt) M. A. Ahmadi, Ex Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of India. I have benefitted from critical discussions with Just (Rt) Rajinder Sachar, Dr. Manzoor Alam, Sri. Salman Khurshid, Mr. Rahman Khan. I wish to thank a number of my colleagues and friends who have made it possible to get this book completed. I have received excellent research support at various times from Mr. -

Sachar Committee Report : a Review Mainstream Weekly

Mainstream Weekly VOL XLV No 01 Sachar Committee Report : A Review Tuesday 24 April 2007, by Anees Chishti The report of the High-Level Committee appointed by the Prime Minister under the chairmanship of Justice Rajindar Sachar, retired Chief Justice of the Delhi High Court, to study the ‘Social, Economic and Educational Status of the Muslim Community of India’, has been a subject of wide discussion in the press, among parliamentarians and other politicians as well as in other informed sections of the society. The seven-member Committee had as its members eminent personalities like Sayid Hamid, former Vice-Chancellor of the Aligarh Muslim University and currently Chancellor, Jamia Hamdard, New Delhi, Prof T.K. Oommen, former Professor at the Jawaharlal Nehru University and a sociologist of world renown, among others. Dr. Abusaleh Shariff, Chief Economist, National Council of Applied Economic Research, who is noted for his perceptive research on various issues of national concern, was the Member-Secretary. There was no woman member: surprising, as the condition of women is very important for any survey of the social scenario among the Muslims. And, the Committee has tried to look at the predicament of the Muslim women in as good a manner as it could. The Committee had several consultants from different disciplines and had commissioned specialists on various aspects of the subject under coverage to write papers for its use in its study of the complex issues. The Committee collected data from the various Censuses, the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO), banks and, of course, from the Central and State Governments. -

Cover Paper Icpp4

4th International Conference on Public Policy (ICPP4) June 26-28, 2019 – Montréal Panel T 01-P12 Session 1 Non Decision Making and Power Title of the paper Non-decision in security policy in India: the United Progressive Alliance Government (2004-14), Muslims and the communal violence bill Author(s) Heewon Kim SOAS, University of London [email protected] Date of presentation June 27, 2019 1 4th International Conference on Public Policy (ICPP4) June 26-28, 2019 – Montréal [DISCUSSION DRAFT: NOT FOR CITATION OR FURTHER CIRCULATION] Key words: Muslim, India, security, communal violence, legislation, non-decision Introduction 1 Social policy formulation is invariably associated with indigenous traditions of statecraft. From welfare to management of migration and diversity, social issues are often framed in terms of tradition, history, and path dependence. However, major ‘critical junctures’ and the enduring persistence of social problems often require a radical departure in the policy cycle. In this policy cycle, key actors operate within an institutional context in which there are ‘formal or informal rules, and conventions, as well as ethical, ideological, and epistemic concerns [that] help to shape actors’ behaviour by conditioning their perception of their interests and the probability of these interests being realised’ (Howlett and Ramesh, 2003: 53). The actors’ ‘assumptive worlds’ or the ‘mental models’ that ‘provide both an interpretation of the environment and a prescription as to how that environment should be structured’ (Arthur and Douglass, 1994: 4), are critical in shaping appropriate solutions. If institutions are heavily biased towards a particular policy path, key actors are likely to adopt a conservative and instrumentalist approach or seek to operate within the ‘rules of the game’ (ibid.). -

(Marxist) Manifesto for the 16Th Lok Sabha Elections, 2014 Part I Introduction the People of India A

Communist Party of India (Marxist) Manifesto for the 16th Lok Sabha Elections, 2014 Part I Introduction The people of India are going to the polls to elect the 16th Lok Sabha. These elections are being held at a time when parliamentary democracy is under onslaught from various quarters. Increasingly democracy is being undermined by the power of big money in politics. Rampant corruption at the highest levels of government and public life is corroding the vitals of the democratic system. The neo-liberal policies pursued by the Congress- led government for a decade has denigrated parliament with policies being determined by a nexus of big business, foreign financial institutions and pliant ruling politicians and bureaucrats. The communal forces headed by the BJP-RSS combine are making a bid for power which poses a threat to the secular –democratic values of the Republic. The people, who have always vitalized the parliamentary system with their deep faith and participation in the democratic system, have to act. They have to assert their rights. They should fight to bring about a change in the policies, for ending the corrupt rule, for strengthening democracy and secularism. Dismal Record of UPA Government The two UPA governments have pursued neo-liberal economic policies which have led to a growing economic divide. This has resulted in pampering the rich and squeezing the people. Effects on People’s Lives Despite the so-called high growth achieved under the UPA government’s earlier years, the lives of the ordinary people have not changed: 36 per cent of women and 34 per cent of men are undernourished; About half (48 per cent) of children under the age of 5 are under nourished and malnourished. -

The Journal of Parliamentary Information

The Journal of Parliamentary Information VOLUMELVIII NO.2 JUNE2012 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI CBS Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd. 24, Ansari Road, Darya Ganj, New Delhi-2 EDITORIAL BOARD Editor : T.K.Viswanathan Secretary-General Lok Sabha AssociateEditors : P.K.Misra Joint Secretary Lok Sabha Secretariat Kalpana Sharma Director Lok Sabha Secretariat AssistantEditors : PulinB.Bhutia Additional Director Lok Sabha Secretariat Parama Chatterjee Joint Director Lok Sabha Secretariat Sanjeev Sachdeva Joint Director Lok Sabha Secretariat © Lok Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi THE JOURNAL OF PARLIAMENTARY INFORMATION VOLUMELVIII NO.2 JUNE2012 CONTENTS PAGE EDITORIAL NOTE 151 ADDRESSES Address by the President to the Parliament 12March2012 152 PARLIAMENTARY EVENTS AND ACTIVITIES ConferencesandSymposia 169 BirthAnniversariesofNationalLeaders 170 ExchangeofParliamentaryDelegations 171 BureauofParliamentaryStudies andTraining 173 PARLIAMENTARY AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENTS 176 SESSIONAL REVIEW LokSabha 188 StateLegislatures 208 RECENT LITERATURE OF PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST 213 APPENDICES I. Statement showing the work transacted during the TenthSessionoftheFifteenthLokSabha 219 II. Statement showing the work transacted during the 225th SessionoftheRajyaSabha 223 III. Statement showing the activities of the Legislatures of the States and Union Territories duringthe period1Januaryto31March 2012 224 IV. List of Bills passed by the Houses of Parliament and Assented to by the President during the period 1Januaryto31March2012 230 (iv) iv The Journal of Parliamentary Information V. List of Bills passed by the Legislatures of the States and the Union Territories during theperiod1Januaryto31March2012 231 VI. Ordinances promulgated by the Union and State Governments during the period 1Januaryto31March2012 240 VII. Party Position in the Lok Sabha, Rajya Sabha and Legislatures oftheStatesandtheUnionTerritories 246 Jai Mata Di final EDITORIAL NOTE The Constitution of India provides for an Address by the President to either House of Parliament or both the Houses assembled together.