13 Relationship and Communality: an Indigenous Perspective On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Native Title Information Talk Delivered at Fernvale Futures on 22 February 2014. Tim Wishart Slide 1 I Acknowledge and Offer M

A Native Title Information Talk Delivered at Fernvale Futures on 22 February 2014. Tim Wishart Slide 1 I acknowledge and offer my respect to the country on which we meet and to the Traditional Owners of this country and to their Old People and Elders. The organisation for which I work, Queensland South Native Title Services is a native title service provider recognised and funded by the Federal Government under the Native Title Act (1993). Slide 2 The area for which QSNTS has statutory recognition under the Native Title Act covers an area spanning Queensland, along the New South Wales border from the Coral Sea to the South Australian border, north to about 250 kilometres north of Mt Isa and running diagonally south eastwards to the coast, marginally south of Sarina. Slide 3 I ought to say that views and opinions expressed are mine and are not necessarily reflective of corporate views or policy of QSNTS. In this conversation I will refer to the Native Title Act as ‘the Act’. But in the consciousness of Queensland Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander society, the expression “the Act” is often a reference to The Aboriginal Protection and Restrictions of the Sale of Opium Act 1897. That legislation was an Act of the Queensland Parliament. As a result of dispersal, malnutrition, use of opium and diseases, all a consequence of European incursion into traditional lands coupled with the attempted genocide that came with that incursion, it was widely believed in Queensland that Aborigines were members of a 'dying race'. In 1894 pressure from some quarters of the community saw the Queensland Government commission Archibald Meston to look at what had conveniently, for the colonising power, become the plight of Aboriginal people. -

Johnathon Davis Thesis

Durithunga – Growing, nurturing, challenging and supporting urban Indigenous leadership in education John Davis-Warra Bachelor of Arts (Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Studies & English) Post Graduate Diploma of Education Supervisors: Associate Professor Beryl Exley Associate Professor Karen Dooley Emeritus Professor Alan Luke Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Education Queensland University of Technology 2017 Keywords Durithunga, education, Indigenous, leadership. Durithunga – Growing, nurturing, challenging and supporting urban Indigenous leadership in education i Language Weaves As highlighted in the following thesis, there are a number of key words and phrases that are typographically different from the rest of the thesis writing. Shifts in font and style are used to accent Indigenous world view and give clear signification to the higher order thought and conceptual processing of words and their deeper meaning within the context of this thesis (Martin, 2008). For ease of transition into this thesis, I have created the “Language Weaves” list of key words and phrases that flow through the following chapters. The list below has been woven in Migloo alphabetical order. The challenge, as I explore in detail in Chapter 5 of this thesis, is for next generations of Indigenous Australian writers to relay textual information in the languages of our people from our unique tumba tjinas. Dissecting my language usage in this way and creating a Language Weaves list has been very challenging, but is part of sharing the unique messages of this Indigenous Education field research to a broader, non- Indigenous and international audience. The following weaves list consists of words taken directly from the thesis. -

Maroochy River Environmental Values and Water Quality

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! M A R O O C H Y R I V E R , I N C L U D I N G A L L T R I B U T A R I E S O F ! T H E R I V E R ! ! M A R O O C H Y R I V E R , I N C L U D I N G A L L T R I B U T A R I E S O F T H E R I V E R ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Part of Basin 141 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 152°50'E 153°E ! 153°10'E ! ! -

Land Cover Change in the South East Queensland Catchments Natural Resource Management Region 2010–11

Department of Science, Information Technology, Innovation and the Arts Land cover change in the South East Queensland Catchments Natural Resource Management region 2010–11 Summary The woody vegetation clearing rate for the SEQ region for 10 2010–11 dropped to 3193 hectares per year (ha/yr). This 9 8 represented a 14 per cent decline from the previous era. ha/year) 7 Clearing rates of remnant woody vegetation decreased in 6 5 2010-11 to 758 ha/yr, 33 per cent lower than the previous era. 4 The replacement land cover class of forestry increased by 3 2 a further 5 per cent over the previous era and represented 1 Clearing Rate (,000 26 per cent of the total woody vegetation 0 clearing rate in the region. Pasture 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 remained the dominant replacement All Woody Clearing Woody Remnant Clearing land cover class at 34 per cent of total clearing. Figure 1. Woody vegetation clearing rates in the South East Queensland Catchments NRM region. Figure 2. Woody vegetation clearing for each change period. Great state. Great opportunity. Woody vegetation clearing by Woody vegetation clearing by remnant status tenure Table 1. Remnant and non-remnant woody vegetation clearing Table 2. Woody vegetation clearing rates in the South East rates in the South East Queensland Catchments NRM region. Queensland Catchments NRM region by tenure. Woody vegetation clearing rate (,000 ha/yr) of Woody vegetation clearing rate (,000 ha/yr) on Non-remnant Remnant -

Senate Official Hansard No

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES Senate Official Hansard No. 4, 2005 TUESDAY, 8 FEBRUARY 2005 FORTY-FIRST PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION—SECOND PERIOD BY AUTHORITY OF THE SENATE INTERNET The Journals for the Senate are available at http://www.aph.gov.au/senate/work/journals/index.htm Proof and Official Hansards for the House of Representatives, the Senate and committee hearings are available at http://www.aph.gov.au/hansard For searching purposes use http://parlinfoweb.aph.gov.au SITTING DAYS—2005 Month Date February 8, 9, 10 March 7, 8, 9, 10, 14, 15, 16, 17 May 10, 11, 12 June 14, 15, 16, 20, 21, 22, 23 August 9, 10, 11, 15, 16, 17, 18 September 5, 6, 7, 8, 12, 13, 14, 15 October 4, 5, 6, 10, 11, 12, 13 November 7, 8, 9, 10, 28, 29, 30 December 1, 5, 6, 7, 8 RADIO BROADCASTS Broadcasts of proceedings of the Parliament can be heard on the following Parliamentary and News Network radio stations, in the areas identified. CANBERRA 1440 AM SYDNEY 630 AM NEWCASTLE 1458 AM GOSFORD 98.1 FM BRISBANE 936 AM GOLD COAST 95.7 FM MELBOURNE 1026 AM ADELAIDE 972 AM PERTH 585 AM HOBART 747 AM NORTHERN TASMANIA 92.5 FM DARWIN 102.5 FM FORTY-FIRST PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION—SECOND PERIOD Governor-General His Excellency Major-General Michael Jeffery, Companion in the Order of Australia, Com- mander of the Royal Victorian Order, Military Cross Senate Officeholders President—Senator the Hon. Paul Henry Calvert Deputy President and Chairman of Committees—Senator John Joseph Hogg Temporary Chairmen of Committees—Senators the Hon. -

Traditional Law and Indigenous Resistance at Moreton Bay 1842-1855

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Southern Queensland ePrints [2005] ANZLH E-Journal Traditional law and Indigenous Resistance at Moreton Bay 1842-1855 LIBBY CONNORS* On the morning of 5 January 1855 when the British settlers of Moreton Bay publicly executed the Dalla-Djindubari man, Dundalli, they made sure that every member of the Brisbane town police was on duty alongside a detachment of native police under their British officer, Lieutenant Irving. Dundalli had been kept in chains and in solitary for the seven months of his confinement in Brisbane Gaol. Clearly the British, including the judge who condemned him, Sir Roger Therry, were in awe of him. The authorities insisted that these precautions were necessary because they feared escape or rescue by his people, a large number of whom had gathered in the scrub opposite the gaol to witness the hanging. Of the ten public executions in Brisbane between 1839 and 1859, including six of Indigenous men, none had excited this much interest from both the European and Indigenous communities.1 British satisfaction over Dundalli’s death is all the more puzzling when the evidence concerning his involvement in the murders for which he was condemned is examined. Dundalli was accused of the murders of Mary Shannon and her employer the pastoralist Andrew Gregor in October 1846, the sawyer William Waller in September 1847 and wounding with intent the lay missionary John Hausmann in 1845. In the first two cases the only witnesses were Mary Shannon’s five year old daughter and a “half- caste” boy living with Gregor whose age was uncertain but described as about ten or eleven years old. -

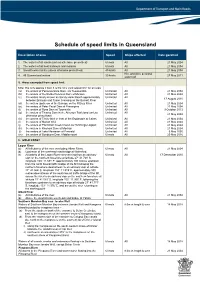

Schedule of Speed Limits in Queensland

Schedule of speed limits in Queensland Description of area Speed Ships affected Date gazetted 1. The waters of all canals (unless otherwise prescribed) 6 knots All 21 May 2004 2. The waters of all boat harbours and marinas 6 knots All 21 May 2004 3. Smooth water limits (unless otherwise prescribed) 40 knots All 21 May 2004 Hire and drive personal 4. All Queensland waters 30 knots 27 May 2011 watercraft 5. Areas exempted from speed limit Note: this only applies if item 3 is the only valid speed limit for an area (a) the waters of Perserverance Dam, via Toowoomba Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (b) the waters of the Bjelke Peterson Dam at Murgon Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (c) the waters locally known as Sandy Hook Reach approximately Unlimited All 17 August 2010 between Branyan and Tyson Crossing on the Burnett River (d) the waters upstream of the Barrage on the Fitzroy River Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (e) the waters of Peter Faust Dam at Proserpine Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (f) the waters of Ross Dam at Townsville Unlimited All 9 October 2013 (g) the waters of Tinaroo Dam in the Atherton Tableland (unless Unlimited All 21 May 2004 otherwise prescribed) (h) the waters of Trinity Inlet in front of the Esplanade at Cairns Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (i) the waters of Marian Weir Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (j) the waters of Plantation Creek known as Hutchings Lagoon Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (k) the waters in Kinchant Dam at Mackay Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (l) the waters of Lake Maraboon at Emerald Unlimited All 6 May 2005 (m) the waters of Bundoora Dam, Middlemount 6 knots All 20 May 2016 6. -

Suicide Prevention for LGBTIQ+ Communities Learnings from the National Suicide Prevention Trial

Science. Compassion. Action. Suicide prevention for LGBTIQ+ communities Learnings from the National Suicide Prevention Trial April 2021 Suicide prevention for LGBTIQ+ communities: Learnings from the National Suicide Prevention Trial ii Acknowledgements Black Dog Institute Black Dog Institute would like to acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as Australia’s First People and Traditional Custodians. We value their cultures, identities, and continuing connection to country, waters, kin and community. We pay our respects to Elders past and present and are committed to making a positive contribution to the mental health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people across Australia. Brisbane North PHN We acknowledge the traditional custodians of this land, the Turrbal and Jagera People of Brisbane, the Gubbi Gubbi people of Caboolture and Bribie Island, the Waka Waka people of Kilcoy and the Ningy Ningy people of Redcliffe. We pay our respects to Elders past, present and emerging for they hold the memories, the traditions, the culture and the hopes of Aboriginal Australia. North Western Melbourne PHN We would like to acknowledge the Wurundjeri People, the Boonerwrung People and the Wathaurong People as the traditional custodians of the land on which our work takes place. We pay our respects to Elders past, present and emerging. Acknowledgement of lived experience We acknowledge those contributing to suicide prevention efforts who are survivors of a suicide attempt, have experienced suicidal behaviour, or have been bereaved or impacted by suicide. Your insights and contributions are critical. Thank you The Black Dog Institute thanks the interviewees and other stakeholders from the Brisbane North Primary Health Network (PHN), North Western Melbourne PHN and the LGBTIQ+ Health Australia for their contributions to the development of this document. -

Principles and Tools for Protecting Australian Rivers

Principles and Tools for Protecting Australian Rivers N. Phillips, J. Bennett and D. Moulton The National Rivers Consortium is a consortium of policy makers, river managers and scientists. Its vision is to achieve continuous improvement in the health of Australia’s rivers. The role of the consortium is coordination and leadership in river restoration and protection, through sharing and enhancing the skills and knowledge of its members. Partners making a significant financial contribution to the National Rivers Consortium and represented on the Board of Management are: Land & Water Australia Murray–Darling Basin Commission Water and Rivers Commission, Western Australia CSIRO Land and Water Published by: Land & Water Australia GPO Box 2182 Canberra ACT 2601 Telephone: (02) 6257 3379 Facsimile: (02) 6257 3420 Email: [email protected] WebSite: www.lwa.gov.au © Land & Water Australia Disclaimer: The information contained in this publication has been published by Land & Water Australia to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the sustainable management of land, water and vegetation. When technical information has been prepared by or contributed by authors external to the Corporation, readers should contact the author(s), and conduct their own enquiries, before making use of that information. Publication data: ‘Principles and Tools for Protecting Australian Rivers’, Phillips, N., Bennett, J. and Moulton, D., Land & Water Australia, 2001. Authors: Phillips, N., Bennett, J. and Moulton, D., Queensland Environmental Protection -

Ship Operations and Activities on the Maroochy River, Final Report to The

Ship operations and activities on the Maroochy River Final Report to the General Manager Final Report to the General Manager, Transport and Main Roads, July 2011 2 of 134 Document control sheet Contact for enquiries and proposed changes If you have any questions regarding this document or if you have a suggestion for improvements, please contact: Contact officer Peter Kleinig Title Area Manager (Sunshine Coast) Phone 07 5477 8425 Version history Version no. Date Changed by Nature of amendment 0.1 03/03/11 Peter Kleinig Initial draft 0.2 09/03/11 Peter Kleinig Minor corrections throughout document 0.3 10/03/11 Peter Kleinig Insert appendices and new maps 0.4 14/03/11 Peter Kleinig Updated recommendations and appendix 1 0.5 13/07/11 Peter Kleinig Updated following meeting 0.6 25/07/11 Peter Kleinig Inserted new maps 1.0 28/07/11 Peter Kleinig Final draft 1.1 28/07/11 Peter Kleinig Final Final Report to the General Manager, Transport and Main Roads, July 2011 3 of 134 Document sign off The following officers have approved this document. Customer Name Captain Richard Johnson Position Regional Harbour Master (Brisbane) Signature Date Reference Group chairperson Name John Kavanagh Position Director (Maritime Services) Signature Date The following persons have endorsed this document. Reference Group members Name Glen Ferguson Position Vice President, Maroochy River Water Ski Association Signature Date Name Graeme Shea Position Representative, Residents of Cook Road, Bli Bli Signature Date Name John Smallwood Position Representative, Sunshine -

A Thesis Submitted by Dale Wayne Kerwin for the Award of Doctor of Philosophy 2020

SOUTHWARD MOVEMENT OF WATER – THE WATER WAYS A thesis submitted by Dale Wayne Kerwin For the award of Doctor of Philosophy 2020 Abstract This thesis explores the acculturation of the Australian landscape by the First Nations people of Australia who named it, mapped it and used tangible and intangible material property in designing their laws and lore to manage the environment. This is taught through song, dance, stories, and paintings. Through the tangible and intangible knowledge there is acknowledgement of the First Nations people’s knowledge of the water flows and rivers from Carpentaria to Goolwa in South Australia as a cultural continuum and passed onto younger generations by Elders. This knowledge is remembered as storyways, songlines and trade routes along the waterways; these are mapped as a narrative through illustrations on scarred trees, the body, engravings on rocks, or earth geographical markers such as hills and physical features, and other natural features of flora and fauna in the First Nations cultural memory. The thesis also engages in a dialogical discourse about the paradigm of 'ecological arrogance' in Australian law for water and environmental management policies, whereby Aqua Nullius, Environmental Nullius and Economic Nullius is written into Australian laws. It further outlines how the anthropocentric value of nature as a resource and the accompanying humanistic technology provide what modern humans believe is the tool for managing ecosystems. In response, today there is a coming together of the First Nations people and the new Australians in a shared histories perspective, to highlight and ensure the protection of natural values to land and waterways which this thesis also explores. -

Annual Report 2007–2008

07 08 NATIONAL NATIVE TITLE TRIBUNAL CONTACT DETAILS Annual Report 2007–2008 Tribunal National Native Title PRINCIPAL REGISTRY (PERTH) NEW SOUTH WALES AND AUSTRALIAN Level 4, Commonwealth Law Courts Building CAPITAL TERRITORY 1 Victoria Avenue Level 25 Perth WA 6000 25 Bligh Street Sydney NSW 2000 GPO Box 9973, Perth WA 6848 GPO Box 9973, Sydney NSW 2001 Telephone: (08) 9268 7272 Facsimile: (08) 9268 7299 Telephone: (02) 9235 6300 Facsimile: (02) 9233 5613 VICTORIA AND TASMANIA Level 8 SOUTH AUSTRALIA 310 King Street Level 10, Chesser House Annual Report Melbourne Vic. 3000 91 Grenfell Street Adelaide SA 5000 GPO Box 9973, Melbourne Vic. 3001 GPO Box 9973, Adelaide SA 5001 Telephone: (03) 9920 3000 2007–2008 Facsimile: (03) 9606 0680 Telephone: (08) 8306 1230 Facsimile: (08) 8224 0939 NORTHERN TERRITORY Level 5, NT House WESTERN AUSTRALIA 22 Mitchell Street Level 11, East Point Plaza Darwin NT 0800 233 Adelaide Terrace Perth WA 6000 GPO Box 9973, Darwin NT 0801 GPO Box 9973, Perth WA 6848 Telephone: (08) 8936 1600 Facsimile: (08) 8981 7982 Telephone: (08) 9268 9700 Facsimile: (08) 9221 7158 QUEENSLAND Level 30, 239 George Street NATIONAL FREECALL NUMBER: 1800 640 501 Brisbane Qld 4000 WEBSITE: www.nntt.gov.au GPO Box 9973, Brisbane Qld 4001 National Native Title Tribunal office hours: Telephone: (07) 3226 8200 8.30am – 5.00pm Facsimile: (07) 3226 8235 8.00am – 4.30pm (Northern Territory) CAIRNS (REGIONAL OFFICE) Level 14, Cairns Corporate Tower 15 Lake Street Cairns Qld 4870 PO Box 9973, Cairns Qld 4870 Telephone: (07) 4048 1500 Facsimile: (07) 4051 3660 Resolution of native title issues over land and waters.