Principles and Tools for Protecting Australian Rivers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maroochy River Environmental Values and Water Quality

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! M A R O O C H Y R I V E R , I N C L U D I N G A L L T R I B U T A R I E S O F ! T H E R I V E R ! ! M A R O O C H Y R I V E R , I N C L U D I N G A L L T R I B U T A R I E S O F T H E R I V E R ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Part of Basin 141 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 152°50'E 153°E ! 153°10'E ! ! -

Land Cover Change in the South East Queensland Catchments Natural Resource Management Region 2010–11

Department of Science, Information Technology, Innovation and the Arts Land cover change in the South East Queensland Catchments Natural Resource Management region 2010–11 Summary The woody vegetation clearing rate for the SEQ region for 10 2010–11 dropped to 3193 hectares per year (ha/yr). This 9 8 represented a 14 per cent decline from the previous era. ha/year) 7 Clearing rates of remnant woody vegetation decreased in 6 5 2010-11 to 758 ha/yr, 33 per cent lower than the previous era. 4 The replacement land cover class of forestry increased by 3 2 a further 5 per cent over the previous era and represented 1 Clearing Rate (,000 26 per cent of the total woody vegetation 0 clearing rate in the region. Pasture 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 remained the dominant replacement All Woody Clearing Woody Remnant Clearing land cover class at 34 per cent of total clearing. Figure 1. Woody vegetation clearing rates in the South East Queensland Catchments NRM region. Figure 2. Woody vegetation clearing for each change period. Great state. Great opportunity. Woody vegetation clearing by Woody vegetation clearing by remnant status tenure Table 1. Remnant and non-remnant woody vegetation clearing Table 2. Woody vegetation clearing rates in the South East rates in the South East Queensland Catchments NRM region. Queensland Catchments NRM region by tenure. Woody vegetation clearing rate (,000 ha/yr) of Woody vegetation clearing rate (,000 ha/yr) on Non-remnant Remnant -

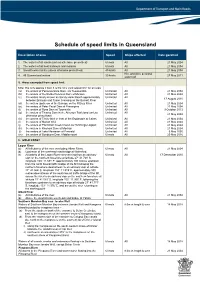

Schedule of Speed Limits in Queensland

Schedule of speed limits in Queensland Description of area Speed Ships affected Date gazetted 1. The waters of all canals (unless otherwise prescribed) 6 knots All 21 May 2004 2. The waters of all boat harbours and marinas 6 knots All 21 May 2004 3. Smooth water limits (unless otherwise prescribed) 40 knots All 21 May 2004 Hire and drive personal 4. All Queensland waters 30 knots 27 May 2011 watercraft 5. Areas exempted from speed limit Note: this only applies if item 3 is the only valid speed limit for an area (a) the waters of Perserverance Dam, via Toowoomba Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (b) the waters of the Bjelke Peterson Dam at Murgon Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (c) the waters locally known as Sandy Hook Reach approximately Unlimited All 17 August 2010 between Branyan and Tyson Crossing on the Burnett River (d) the waters upstream of the Barrage on the Fitzroy River Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (e) the waters of Peter Faust Dam at Proserpine Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (f) the waters of Ross Dam at Townsville Unlimited All 9 October 2013 (g) the waters of Tinaroo Dam in the Atherton Tableland (unless Unlimited All 21 May 2004 otherwise prescribed) (h) the waters of Trinity Inlet in front of the Esplanade at Cairns Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (i) the waters of Marian Weir Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (j) the waters of Plantation Creek known as Hutchings Lagoon Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (k) the waters in Kinchant Dam at Mackay Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (l) the waters of Lake Maraboon at Emerald Unlimited All 6 May 2005 (m) the waters of Bundoora Dam, Middlemount 6 knots All 20 May 2016 6. -

Ship Operations and Activities on the Maroochy River, Final Report to The

Ship operations and activities on the Maroochy River Final Report to the General Manager Final Report to the General Manager, Transport and Main Roads, July 2011 2 of 134 Document control sheet Contact for enquiries and proposed changes If you have any questions regarding this document or if you have a suggestion for improvements, please contact: Contact officer Peter Kleinig Title Area Manager (Sunshine Coast) Phone 07 5477 8425 Version history Version no. Date Changed by Nature of amendment 0.1 03/03/11 Peter Kleinig Initial draft 0.2 09/03/11 Peter Kleinig Minor corrections throughout document 0.3 10/03/11 Peter Kleinig Insert appendices and new maps 0.4 14/03/11 Peter Kleinig Updated recommendations and appendix 1 0.5 13/07/11 Peter Kleinig Updated following meeting 0.6 25/07/11 Peter Kleinig Inserted new maps 1.0 28/07/11 Peter Kleinig Final draft 1.1 28/07/11 Peter Kleinig Final Final Report to the General Manager, Transport and Main Roads, July 2011 3 of 134 Document sign off The following officers have approved this document. Customer Name Captain Richard Johnson Position Regional Harbour Master (Brisbane) Signature Date Reference Group chairperson Name John Kavanagh Position Director (Maritime Services) Signature Date The following persons have endorsed this document. Reference Group members Name Glen Ferguson Position Vice President, Maroochy River Water Ski Association Signature Date Name Graeme Shea Position Representative, Residents of Cook Road, Bli Bli Signature Date Name John Smallwood Position Representative, Sunshine -

Maroochy River Environmental Values and Water Quality Objectives Basin No

Environmental Protection (Water) Policy 2009 Maroochy River environmental values and water quality objectives Basin No. 141 (part), including all tributaries of the Maroochy River July 2010 Prepared by: Water Quality & Ecosystem Health Policy Unit Department of Environment and Resource Management © State of Queensland (Department of Environment and Resource Management) 2010 The Department of Environment and Resource Management authorises the reproduction of textual material, whole or part, in any form, provided appropriate acknowledgement is given. This publication is available in alternative formats (including large print and audiotape) on request. Contact (07) 322 48412 or email <[email protected]> July 2010 Document Ref Number Main parts of this document and what they contain • Scope of waters covered Introduction • Key terms / how to use document (section 1) • Links to WQ plan (map) • Mapping / water type information • Further contact details • Amendment provisions • Source of EVs for this document Environmental Values • Table of EVs by waterway (EVs - section 2) - aquatic ecosystem - human use • Any applicable management goals to support EVs • How to establish WQOs to protect Water Quality Objectives all selected EVs (WQOs - section 3) • WQOs in this document, for - aquatic ecosystem EV - human use EVs • List of plans, reports etc containing Ways to improve management actions relevant to the water quality waterways in this area (section 4) • Definitions of key terms including an Dictionary explanation table of all (section 5) environmental values • An accompanying map that shows Accompanying WQ Plan water types, levels of protection and (map) other information contained in this document iii CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 WATERS TO WHICH THIS DOCUMENT APPLIES ............................................................................. -

The 2053 South Queensland Flood

THE 2053 SOUTH QUEENSLAND FLOOD Only Young Water Professionals Need Attend ABSTRACT A ‘roadshow’ of flood engineers in the early 1980s ‘prophesised’ the flooding that occurred in South East Queensland (SE QLD) during 2011 to 2015. The events of 2011 to 2015 may have given increased credibility to a long-held notion that SE QLD may be subject to a 40-year flood cycle. This paper examines the data on flooding within the ten major SE QLD catchments, bounded by three mountain ranges and comprising more than 63,000 km2. The purpose was to test the existence and the strength of any regularity to flooding in this well-populated region of Australia. The approach identifies the flooding that occurred during predetermined five-year periods that were 35 years apart – the 40-year cycle – and the flooding that occurred outside of these nominated 5-year periods. The basic statistics were weighted for the length of flood record, catchment area, ranking of flood, and a combination of these factors. The results indicate that 69-87% of major floods in SE QLD have occurred within a set of five-year periods exactly 35 years apart. No explanation is offered at this stage of the research. The implications for traditional hydrologic methods are outlined. Keywords: Flooding, flood cycles, regularity, flood frequency INTRODUCTION The early years of the 1970s in South East Queensland was a period of multiple flooding events, remembered mostly for the January 1974 flooding of Brisbane. The following decade was one that experienced widespread estuarine development, where State and Local Government concerns that the development be above the 1in100AEP flood on top of a cyclonic surge, with allowance for future water level rises due to global climatic change, engaged a community of engineers who specialised in relevant fields. -

Flood Risk Management in Australia Building Flood Resilience in a Changing Climate

Flood Risk Management in Australia Building flood resilience in a changing climate December 2020 Flood Risk Management in Australia Building flood resilience in a changing climate Neil Dufty, Molino Stewart Pty Ltd Andrew Dyer, IAG Maryam Golnaraghi (lead investigator of the flood risk management report series and coordinating author), The Geneva Association Flood Risk Management in Australia 1 The Geneva Association The Geneva Association was created in 1973 and is the only global association of insurance companies; our members are insurance and reinsurance Chief Executive Officers (CEOs). Based on rigorous research conducted in collaboration with our members, academic institutions and multilateral organisations, our mission is to identify and investigate key trends that are likely to shape or impact the insurance industry in the future, highlighting what is at stake for the industry; develop recommendations for the industry and for policymakers; provide a platform to our members, policymakers, academics, multilateral and non-governmental organisations to discuss these trends and recommendations; reach out to global opinion leaders and influential organisations to highlight the positive contributions of insurance to better understanding risks and to building resilient and prosperous economies and societies, and thus a more sustainable world. The Geneva Association—International Association for the Study of Insurance Economics Talstrasse 70, CH-8001 Zurich Email: [email protected] | Tel: +41 44 200 49 00 | Fax: +41 44 200 49 99 Photo credits: Cover page—Markus Gebauer / Shutterstock.com December 2020 Flood Risk Management in Australia © The Geneva Association Published by The Geneva Association—International Association for the Study of Insurance Economics, Zurich. 2 www.genevaassociation.org Contents 1. -

Predicting and Regulating Boat-Generated Waves Within Rivers and Sheltered Waterways

Predicting And Regulating Boat-generated Waves Within Rivers And Sheltered Waterways Associate Professor Gregor Macfarlane Australian Maritime College, University of Tasmania SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA | 14 -18 October 2018 MANAGED BY • All marine vessels generate waves. • Vessels now go faster, further and more often. • New issues for other users and the environment: • bank erosion; • damage to moored vessels, jetties and other marine structures; • endanger people working or enjoying activities in small craft or close to the shore. SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA | 14 -18 October 2018 MANAGED BY SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA | 14 -18 October 2018 MANAGED BY Gordon River, south-west Tasmania SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA | 14 -18 October 2018 MANAGED BY SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA | 14 -18 October 2018 MANAGED BY SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA | 14 -18 October 2018 MANAGED BY SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA | 14 -18 October 2018 MANAGED BY Test Sites Boat / Ship Wave Wake Test Sites : • Gordon River, Tasmania • Strahan Harbour, Tasmania • Tamar River, Tasmania • Derwent River, Tasmania • Sydney Harbour (5 locations), Sydney, New South Wales • Parramatta River, Sydney, New South Wales • Hunter River, Newcastle, New South Wales • Brisbane River, Bulimba, Brisbane, Queensland • Brisbane River, upstream of Bremer River, Queensland • Noosa River, Noosa, Brisbane, Queensland • Maroochy River, Maroochydore, Queensland • Swan River, Perth, Western Australia • Canning River, Perth, Western Australia • Daly River, Malak Malak region, Northern Territory • Willamette River, Oregon, United States of America SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA | 14 -18 October 2018 MANAGED BY Need to take action… • regulate vessel operations (vessel speed and/or route); • optimise the vessel design; or, • implement remedial measures on shore. SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA | 14 -18 October 2018 MANAGED BY Need to take action…and planning in the early stages • regulate vessel operations (vessel speed and/or route); • optimise the vessel design; or, • implement remedial measures on shore. -

Surface Water Network Review Final Report

Surface Water Network Review Final Report 16 July 2018 This publication has been compiled by Operations Support - Water, Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy. © State of Queensland, 2018 The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence. Under this licence you are free, without having to seek our permission, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. Note: Some content in this publication may have different licence terms as indicated. For more information on this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The information contained herein is subject to change without notice. The Queensland Government shall not be liable for technical or other errors or omissions contained herein. The reader/user accepts all risks and responsibility for losses, damages, costs and other consequences resulting directly or indirectly from using this information. Interpreter statement: The Queensland Government is committed to providing accessible services to Queenslanders from all culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. If you have difficulty in understanding this document, you can contact us within Australia on 13QGOV (13 74 68) and we will arrange an interpreter to effectively communicate the report to you. Surface -

Baddiley Peter Second Statement Annex PB2-816.Pdf

In the matter of the Commissions of Inquiry Act 1950 Commissions of Inquiry Order (No.1) 2011 Queensland Floods Commission of Inquiry Second Witness Statement of Peter Baddiley Annexure “PB2-8(16)” PB2-8(16) 1 PB2-8(16) 2 PB2-8 (16) FLDWARN Coastal Rs Maryborough south 1 December 2010 to 31 January 2011 TO::BOM612+BOM613+BOM614+BOM615+BOM617+BOM618 IDQ20780 Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology Queensland FLOOD WARNING FOR COASTAL STREAMS AND ADJACENT INLAND CATCHMENTS FROM MARYBOROUGH TO THE NSW BORDER Issued at 6:46 PM on Saturday the 11th of December 2010 by the Bureau of Meteorology, Brisbane. Heavy rainfall during Saturday has resulted in fast level rises in coastal catchments and adjacent inland catchments. The heaviest rainfall to 6pm Saturday has been in the Pine Rivers area and coastal areas from Brisbane to the Gold Coast. Further rainfall is forecast overnight with fast rises and some minor flooding expected. Rainfall totals in the 9 hours to 6pm include: Wynnum 100mm, Mitchelton 76mm, Logan 65mm, Coomera 46mm , Brisbane 74mm and Beerwah 60m. ## Next Issue: The next warning will be issued by 8am Sunday. Latest River Heights: nil. Warnings and River Height Bulletins are available at http://www.bom.gov.au/qld/flood/ . Flood Warnings are also available on telephone 1300 659 219 at a low call cost of 27.5 cents, more from mobile, public and satellite phones. TO::BOM612+BOM613+BOM614+BOM615+BOM617+BOM618 IDQ20780 Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology Queensland FLOOD WARNING FOR COASTAL STREAMS AND ADJACENT INLAND CATCHMENTS FROM MARYBOROUGH TO BRISBANE Issued at 8:19 AM on Sunday the 12th of December 2010 by the Bureau of Meteorology, Brisbane. -

1 Title 2 Gully Erosion in Sub-Tropical South‒ East Queensland, Australia

1 Title 2 Gully erosion in sub-tropical south‒ east Queensland, Australia. 3 Nina E. Saxtona*, Jon M. Olleya, Stuart Smitha, Doug P. Warda and Calvin W. 4 Rosea 5 a 6 Australian Rivers Institute, Griffith University, 170 Kessels Road, Nathan, QLD 7 4111, Australia 8 * Corresponding author: N. E. Saxton 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 G r i f f i t h U n Abstract i v Analysis of aerial photographs shows that gully erosion in three catchments in e r s south‒ east Queensland, Australia, was initiated by post‒ European settlement. i t Analysis of historical rainfall and runoff show for two of the catchments, gully y , initiation occurred during wet decadal periods. Historical descriptions of the 1 settlement of south‒ east Queensland and Moreton Bay detail significant 7 0 changes in landuse and clearing of vegetation for grazing of domestic animals K e and urban development since 1842. Historical gully erosion rates varied from s s 14‒ 1826 m2yr‒ 1 and erosion rates are positively correlated with catchment area e l s x slope. Analysis of gully erosion rates showed a linear increase in planemetric R area over time. Together, these data show gully initiation in three catchments in o a d 24 south‒ east Queensland is associated with post‒ European settlement land use 25 practices and above average rainfall and runoff. Initiation of gullying across the 26 region is similar to previous studies in south‒ east Australia and highlights the 27 sensitivity of the landscape to vegetation clearing and alternating periods of 28 above average rainfall and drought. -

Oreochromis Mossambicus and Tilapia Mariae Distribution Throughout Qld - As at November 2019 140°E 145°E 150°E 155°E

Oreochromis mossambicus and Tilapia mariae distribution throughout Qld - as at November 2019 140°E 145°E 150°E 155°E Gulf Catchments Outline Murray-Darling Basin Outline List of infected catchments in Qld: Oreochromis mossambicus: BAFFLE CREEK BARRON RIVER BLACK RIVER BRISBANE RIVER BRUNSWICK RIVER BURDEKIN RIVER S BURNETT RIVER S ° ° 5 BURRUM RIVER 5 1 1 CALLIOPE RIVER DON RIVER ENDEAVOUR RIVER FITZROY RIVER (QLD) HAUGHTON RIVER HERBERT RIVER Cairns KOLAN RIVER LOGAN-ALBERT RIVERS MAROOCHY RIVER MARY RIVER (QLD) NOOSA RIVER PINE RIVER PIONEER RIVER ROSS RIVER SOUTH COAST Townsville Tilapia mariae: MURRAY RIVER S S ° JOHNSTONE RIVER ° 0 0 2 2 Oreochromis mossambicus and Tilapia mariae: BARRON RIVER Mackay WALSH RIVER MULGRAVE-RUSSELL RIVER TULLY RIVER Rockhampton Emerald Bundaberg S Tambo S ° ° 5 5 2 2 Roma Chinchilla Dalby Brisbane Toowoomba Warwick Moree S Brewarrina S ° ° 0 Bourke 0 3 Walgett 3 Armidale Broken Hill Dubbo Orange Sydney S S ° ° 5 5 3 Wagga Wagga 3 These datasets are licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia Author: Department of License. To view a copy of this license, visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/ Agriculture & Fisheries While every care is taken to ensure the accuracy of these data, all data custodians and/or the Date: 29/10/2019 State of Queensland makes no representations or warranties about its accuracy, reliability, ± completeness or suitability for any particular purpose and disclaims all responsibility and all Co-ord Sys: GCS GDA 1994 liability (including without limitation, liability in negligence) for all expenses, losses, damages (including indirect or consequential damage) and costs to which you might incur as a result Datum: GDA 1994 0 220 440 of the data being inaccurate or incomplete in any way and for any reason.