Norway's Whole-Of-Government Approach and Its Engagement With

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United Nations Infantry Battalion Manual Volume I

United Nations Infantry Battalion Manual Volume I asdf DEPARTMENT OF PEACEKEEPING OPERATIONS DEPARTMENT OF FIELD SUPPORT AUGUST 2012 United Nations Infantry Battalion Manual Volume I asdf DEPARTMENT OF PEACEKEEPING OPERATIONS DEPARTMENT OF FIELD SUPPORT AUGUST 2012 The first UN Infantry Battalion was deployed as part of United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF-I). UN infantry soldiers march in to Port Said, Egypt, in December 1956 to assume operational responsibility. asdf ‘The United Nations Infantry Battalion is the backbone of United Nations peacekeeping, braving danger, helping suffering civilians and restoring stability across war-torn societies. We salute your powerful contribution and wish you great success in your life-saving work.’ BAN Ki-moon United Nations Secretary-General United Nations Infantry Battalion Manual ii Preface I am very pleased to introduce the United Nations Infantry Battalion Man- ual, a practical guide for commanders and their staff in peacekeeping oper- ations, as well as for the Member States, the United Nations Headquarters military and other planners. The ever-changing nature of peacekeeping operations with their diverse and complex challenges and threats demand the development of credible response mechanisms. In this context, the military components that are deployed in peacekeeping operations play a pivotal role in maintaining safety, security and stability in the mission area and contribute meaningfully to the achievement of each mission mandate. The Infantry Battalion con- stitutes the backbone of any peacekeeping -

The Constitutional Role of the Privy Council and the Prerogative 3

Foreword The Privy Council is shrouded in mystery. As Patrick O’Connor points out, even its statutory definition is circular: the Privy Council is defined by the Interpretation Act 1978 as the members of ‘Her Majesty’s Honourable Privy Council’. Many people may have heard of its judicial committee, but its other roles emerge from the constitutional fog only occasionally – at their most controversial, to dispossess the Chagos Islanders of their home, more routinely to grant a charter to a university. Tracing its origin back to the twelfth or thirteen century, its continued existence, if considered at all, is regarded as vaguely charming and largely formal. But, as the vehicle that dispossessed those living on or near Diego Garcia, the Privy Council can still display the power that once it had more widely as an instrument of feudal rule. Many of its Orders in Council bypass Parliament but have the same force as democratically passed legislation. They are passed, unlike such legislation, without any express statement of compatibility with the European Convention on Human Rights. What is more, Orders in Council are not even published simultaneously with their passage. Two important orders relating to the treatment of the Chagos Islanders were made public only five days after they were passed. Patrick, originally inspired by his discovery of the essay that the great nineteenth century jurist Albert Venn Dicey wrote for his All Souls Fellowship, provides a fascinating account of the history and continuing role of the Privy Council. He concludes by arguing that its role, and indeed continued existence, should be subject to fundamental review. -

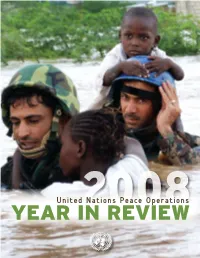

Year in Review 2008

United Nations Peace Operations YEAR IN2008 REVIEW asdf TABLE OF CONTENTS 12 ] UNMIS helps keep North-South Sudan peace on track 13 ] MINURCAT trains police in Chad, prepares to expand 15 ] After gaining ground in Liberia, UN blue helmets start to downsize 16 ] Progress in Côte d’Ivoire 18 ] UN Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea is withdrawn 19 ] UNMIN assists Nepal in transition to peace and democracy 20 ] Amid increasing insecurity, humanitarian and political work continues in Somalia 21 ] After nearly a decade in Kosovo, UNMIK reconfigures 23 ] Afghanistan – Room for hope despite challenges 27 ] New SRSG pursues robust UN mandate in electoral assistance, reconstruction and political dialogue in Iraq 29 ] UNIFIL provides a window of opportunity for peace in southern Lebanon 30 ] A watershed year for Timor-Leste 33 ] UN continues political and peacekeeping efforts in the Middle East 35 ] Renewed hope for a solution in Cyprus 37 ] UNOMIG carries out mandate in complex environment 38 ] DFS: Supporting peace operations Children of Tongo, Massi, North Kivu, DRC. 28 March 2008. UN Photo by Marie Frechon. Children of Tongo, 40 ] Demand grows for UN Police 41 ] National staff make huge contributions to UN peace 1 ] 2008: United Nations peacekeeping operations observes 60 years of operations 44 ] Ahtisaari brings pride to UN peace efforts with 2008 Nobel Prize 6 ] As peace in Congo remains elusive, 45 ] Security Council addresses sexual violence as Security Council strengthens threat to international peace and security MONUC’s hand [ Peace operations facts and figures ] 9 ] Challenges confront new peace- 47 ] Peacekeeping contributors keeping mission in Darfur 48 ] United Nations peacekeeping operations 25 ] Peacekeepers lead response to 50 ] United Nations political and peacebuilding missions disasters in Haiti 52 ] Top 10 troop contributors Cover photo: Jordanian peacekeepers rescue children 52 ] Surge in uniformed UN peacekeeping personnel from a flooded orphanage north of Port-au-Prince from1991-2008 after the passing of Hurricane Ike. -

Reputation As a Disciplinarian of International Organizations Kristina Daugirdas University of Michigan Law School, [email protected]

University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository Articles Faculty Scholarship 2019 Reputation as a Disciplinarian of International Organizations Kristina Daugirdas University of Michigan Law School, [email protected] Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles/2035 Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles Part of the International Humanitarian Law Commons, Organizations Law Commons, and the Public Law and Legal Theory Commons Recommended Citation Daugirdas, Kristina. "Reputation as a Disciplinarian of International Organizations." Am. J. Int'l L. 113, no. 2 (2019): 221-71. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright © 2019 by The American Society of International Law doi:10.1017/ajil.2018.122 REPUTATION AS A DISCIPLINARIAN OF INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS By Kristina Daugirdas* ABSTRACT As a disciplinarian of international organizations, reputation has serious shortcomings. Even though international organizations have strong incentives to maintain a good reputation, reputational concerns will sometimes fail to spur preventive or corrective action. Organizations have multiple audiences, so efforts to preserve a “good” reputation may pull organizations in many different directions, and steps taken to preserve a good reputation will not always be salutary. Recent incidents of sexual violence by UN peacekeepers in the Central African Republic illustrate these points. On April 29, 2015, The Guardian published an explosive story based on a leaked UN document.1 The document described allegations against French troops who had been deployed to the Central African Republic pursuant to a mandate established by the Security Council. -

Roles and Responsibilities of the Centres of Government

4. INSTITUTIONS Roles and responsibilities of the centres of government The centre of government (CoG), also known as the (26 countries). Australia and the Netherlands use a wide Cabinet Office, Office of the President, Privy Council, range of instruments, including performance management General Secretariat of the Government, among others, is and providing written guidance to ministries. Hungary and the structure that supports the Prime Minister and the Spain, on the other hand, use only regular cabinet meetings Council of Ministers (i.e. the regular meeting of government for this purpose. ministers). The CoG includes the body that serves the head The CoG is involved in strategic planning in all OECD countries, of government and the Council, as well as the office that except for Turkey – where the Ministry of Development is specifically serves the head of government (e.g. Prime mandated with this task. In six countries (Chile, Estonia, Minister’s Office). Iceland, Lithuania, Mexico and the United Kingdom) the The scope of the responsibilities assigned to such a responsibility is shared with the Ministry of Finance. structure varies largely among countries. In Greece, the CoG Transition planning and management falls under the sole is responsible for 11 functions, including communication responsibility of CoG in 21 countries and is shared with with the public, policy formulation and analysis. In Ireland other bodies in another 11. In five of these, each ministry is and Japan, only the preparation of cabinet meetings falls responsible for briefing the incoming government. Relations entirely under CoG responsibility. When considering both with Parliament fall within the scope of CoG responsibilities shared and exclusive tasks, the CoG has the broadest in all OECD countries. -

Images of Male Political Leaders in France and Norway

Reconsidering Politics as a Man's World: Images of Male Political Leaders in France and Norway Anne Krogstad and Aagoth Storvik Researchers have often pointed to the masculine norms that are integrated into politics. This article explores these norms by studying male images of politics and power in France and Norway from 1945 to 2009. Both dress codes and more general leadership styles are discussed. The article shows changes in political aesthetics in both countries since the Second World War. The most radical break is seen in the way Norwegian male politicians present themselves. The traditional Norwegian leadership ethos of piety, moderation, and inward orientation is still important, but it is not as self- effacing and inelegant as it used to be. However, compared to the leaders in French politics, who still live up to a heroic leadership ideal marked by effortless superiority and seduction, the Norwegian leaders look modest. To explain the differences in political self-presentation and evaluation we argue that cultural repertoires are not only national constructions but also gendered constructions. Keywords: photographs; politics; aesthetics; gender; national cultural repertoires 1 When people think of presidents and prime ministers, they usually think of the incumbents of these offices.1 In both France and Norway, these incumbents have, with the exception of Prime Minister Edith Cresson in France and Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland in Norway, been male (and white). Researchers have often pointed to the masculine norms which are integrated into the expectations of what political officeholders should look like and be. Politics, it is claimed, is still very much a man’s world.2 However, maleness does not express general political leadership in a simple and undifferentiated way. -

Neo-European Worlds

Garner: Europeans in Neo-European Worlds 35 EUROPEANS IN NEO-EUROPEAN WORLDS: THE AMERICAS IN WORLD HISTORY by Lydia Garner In studies of World history the experience of the first colonial powers in the Americas (Spain, Portugal, England, and france) and the processes of creating neo-European worlds in the new environ- ment is a topic that has received little attention. Matters related to race, religion, culture, language, and, since of the middle of the last century of economic progress, have divided the historiography of the Americas along the lines of Anglo-Saxon vs. Iberian civilizations to the point where the integration of the Americas into World history seems destined to follow the same lines. But in the broader perspec- tive of World history, the Americas of the early centuries can also be analyzed as the repository of Western Civilization as expressed by its constituent parts, the Anglo-Saxon and the Iberian. When transplanted to the environment of the Americas those parts had to undergo processes of adaptation to create a neo-European world, a process that extended into the post-colonial period. European institu- tions adapted to function in the context of local socio/economic and historical realities, and in the process they created apparently similar European institutions that in reality became different from those in the mother countries, and thus were neo-European. To explore their experience in the Americas is essential for the integration of the history of the Americas into World history for comparative studies with the European experience in other regions of the world and for the introduction of a new perspective on the history of the Americas. -

United Nations Force Headquarters Handbook

United Nations Force Headquarters Handbook UNITED NATIONS FORCE HEADQUARTERS HANDBOOK November 2014 United Nations Force Headquarters Handbook Foreword The United Nations Force Headquarters Handbook aims at providing information that will contribute to the understanding of the functioning of the Force HQ in a United Nations field mission to include organization, management and working of Military Component activities in the field. The information contained in this Handbook will be of particular interest to the Head of Military Component I Force Commander, Deputy Force Commander and Force Chief of Staff. The information, however, would also be of value to all military staff in the Force Headquarters as well as providing greater awareness to the Mission Leadership Team on the organization, role and responsibilities of a Force Headquarters. Furthermore, it will facilitate systematic military planning and appropriate selection of the commanders and staff by the Department of Peacekeeping Operations. Since the launching of the first United Nations peacekeeping operations, we have collectively and systematically gained peacekeeping expertise through lessons learnt and best practices of our peacekeepers. It is important that these experiences are harnessed for the benefit of current and future generation of peacekeepers in providing appropriate and clear guidance for effective conduct of peacekeeping operations. Peacekeeping operations have evolved to adapt and adjust to hostile environments, emergence of asymmetric threats and complex operational challenges that require a concerted multidimensional approach and credible response mechanisms to keep the peace process on track. The Military Component, as a main stay of a United Nations peacekeeping mission plays a vital and pivotal role in protecting, preserving and facilitating a safe, secure and stable environment for all other components and stakeholders to function effectively. -

Fact Sheet on "Overview of Norway"

Legislative Council Secretariat FSC21/13-14 FACT SHEET Overview of Norway Geography Land area Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is located in northern Europe. It has a total land area of 304 282 sq km divided into 19 counties. Oslo is the capital of the country and seat of government. Demographics Population Norway had a population of about 5.1 million at end-July 2014. The majority of the population were Norwegian (94%), followed by ethnic minority groups such as Polish, Swedish and Pakistanis. History Political ties Norway has a history closely linked to that of its immediate with neighbours, Sweden and Denmark. Norway had been an Denmark and independent kingdom in its early period, but lost its Sweden independence in 1380 when it entered into a political union with Denmark through royal intermarriage. Subsequently both Norway and Denmark formed the Kalmar Union with Sweden in 1397, with Denmark as the dominant power. Following the withdrawal of Sweden from the Union in 1523, Norway was reduced to a dependence of Denmark in 1536 under the Danish-Norwegian Realm. Union The Danish-Norwegian Realm was dissolved in between January 1814, when Denmark ceded Norway to Sweden as Norway and part of the Kiel Peace Agreement. That same year Sweden Norway – tired of forced unions – drafted and adopted its own Constitution. Norway's struggle for independence was subsequently quelled by a Swedish invasion. In the end, Norwegians were allowed to keep their new Constitution, but were forced to accept the Norway-Sweden Union under a Swedish king. Research Office page 1 Legislative Council Secretariat FSC21/13-14 History (cont'd) Independence The Sweden-Norway Union was dissolved in 1905, after the of Norway Norwegians voted overwhelmingly for independence in a national referendum. -

From the Tito-Stalin Split to Yugoslavia's Finnish Connection: Neutralism Before Non-Alignment, 1948-1958

ABSTRACT Title of Document: FROM THE TITO-STALIN SPLIT TO YUGOSLAVIA'S FINNISH CONNECTION: NEUTRALISM BEFORE NON-ALIGNMENT, 1948-1958. Rinna Elina Kullaa, Doctor of Philosophy 2008 Directed By: Professor John R. Lampe Department of History After the Second World War the European continent stood divided between two clearly defined and competing systems of government, economic and social progress. Historians have repeatedly analyzed the formation of the Soviet bloc in the east, the subsequent superpower confrontation, and the resulting rise of Euro-Atlantic interconnection in the west. This dissertation provides a new view of how two borderlands steered clear of absorption into the Soviet bloc. It addresses the foreign relations of Yugoslavia and Finland with the Soviet Union and with each other between 1948 and 1958. Narrated here are their separate yet comparable and, to some extent, coordinated contests with the Soviet Union. Ending the presumed partnership with the Soviet Union, the Tito-Stalin split of 1948 launched Yugoslavia on a search for an alternative foreign policy, one that previously began before the split and helped to provoke it. After the split that search turned to avoiding violent conflict with the Soviet Union while creating alternative international partnerships to help the Communist state to survive in difficult postwar conditions. Finnish-Soviet relations between 1944 and 1948 showed the Yugoslav Foreign Ministry that in order to avoid invasion, it would have to demonstrate a commitment to minimizing security risks to the Soviet Union along its European political border and to not interfering in the Soviet domination of domestic politics elsewhere in Eastern Europe. -

KEY QUESTIONS the Big Six

Norway Donor Profile KEY QUESTIONS the big six Who are the main actors in Norway's development cooperation? MFA steers strategy and established a Minister of which are partly reported as ODA, and the Ministry of International Development post in 2018; embassies Education and Research. execute bilateral programs Norwegian embassies lead programming of bilateral co- Norway’s coalition government is led by Prime Minister operation in partner countries, on the basis of the priori- (PM) Erna Solberg. The Conservative Party (H) of Solberg ties outlined in the MFA’s annual appropriation letters. and the Progress Party (FrP), both in power since 2013, Leadership and program officers in Norwegian embas- were re-elected in October 2017. The Liberal Party (V) sies, and regional sections within the MFA’s Department joined the coalition in January 2018, and the Christian for Regional Affairs and Development play a key role in Democratic Party (KrF) joined in January 2019, after a developing these letters. Within these priorities, embas- year of cooperation with the government on an ad-hoc sies have ample financial and programming authority. basis. They develop annual work plans and agreements for bi- lateral programs, which are then reviewed by Norad. The Ministry for Foreign Affairs (MFA) is responsible for setting the strategic direction of development coopera- Norad, the Norwegian Agency for Development Coopera- tion. Since October 2017 it has been led by former Minis- tion, and Norfund, Norway’s development finance insti- ter of Defense Ine Eriksen Søreide (H). In January 2018, tution, play key roles in policy development, priority set- the minister of the European Economic Area and EU af- ting, and implementation. -

Siam's Political Future : Documents from the End of the Absolute Monarchy

SIAM'S POLITICAL FUTURE: DOCUMENTS FROM THE END OF THE ABSOLUTE MONARCHY THE CORNELL UNIVERSITY SOUTHEAST ASIA PROGRAM The Southeast Asia Program was organized at Cornell University in the Department of Far Eastern Studies in 1950. It is a teaching and research program of interdisciplinary studies in the hmnanities, social sciences, and some natural sciences. It deals with Southeast Asia as a region, and with the individual cowitries of the area: Brunei, Burma, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. The activities of the program are carried on _both at Cornell and in Southeast Asia. They include an Wldergraduate and graduate curriculum at Cornell which provides instruction by specialists in Southeast Asian cultural history and present-day affairs and offers intensive training in each of the major languages of the area. The Program sponsors group research projects on Thailand, on Indonesia, on the Philippines, and on the area's Chinese minorities. At the same time, individual staff and students of the Program have done field research in every Southeast Asian country. A list of publications relating to Southeast Asia which may be obtained on prepaid order directly from the Program is given at the end of this volume. Information on Program staff, fellowships, requirements for degrees, and current course offerings will be found in an Announcement of the Depaxatment of Asian Stu.dies, obtainable from the Director, Southeast Asia Program, 120 Uris Hall, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14850. 11 SIAM'S POLITICAL FUTURE: DOCUMENTS FROM THE END OF THE ABSOLUTE MONARCHY Compiled and edited with introductions by Benjamin A.